DAFA Barbara Wolfram - Genealogic Perspectives on Autosoziobiography

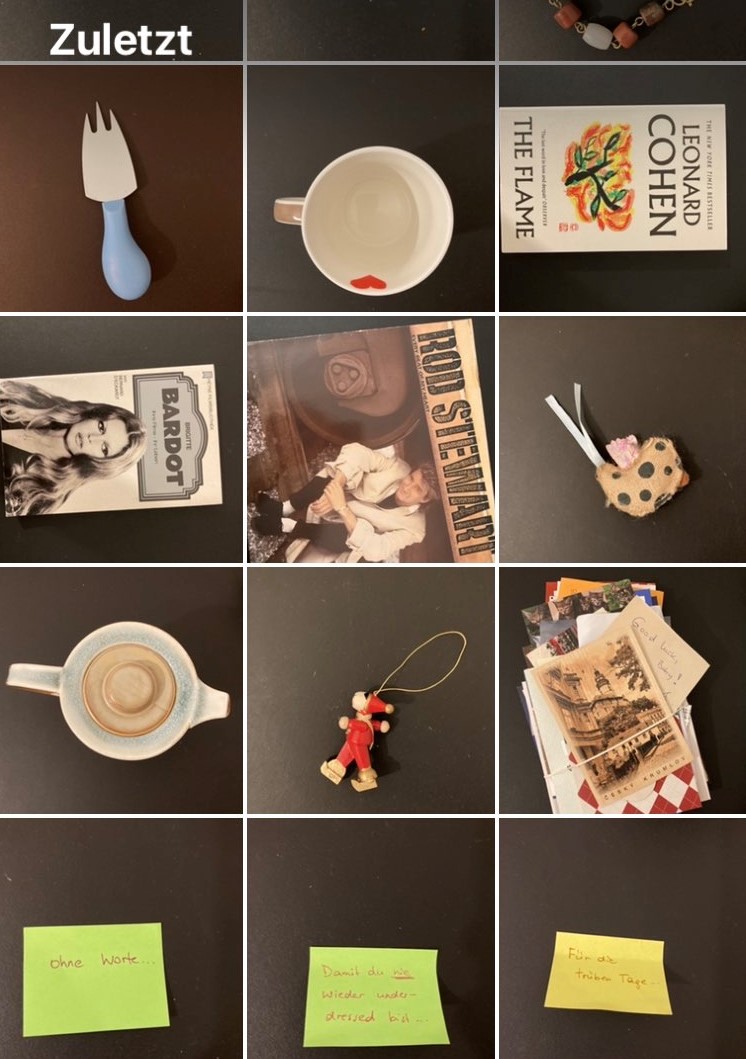

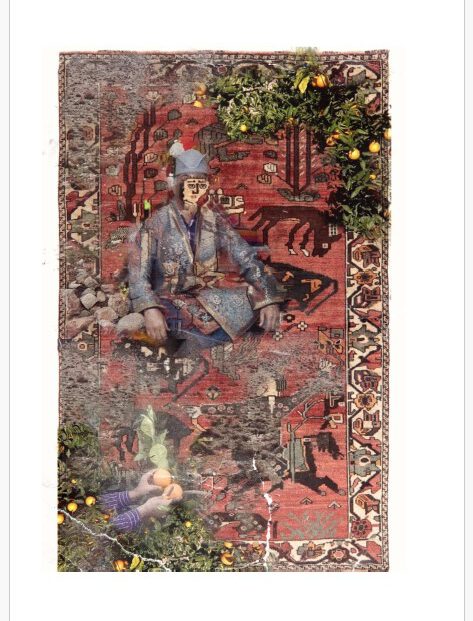

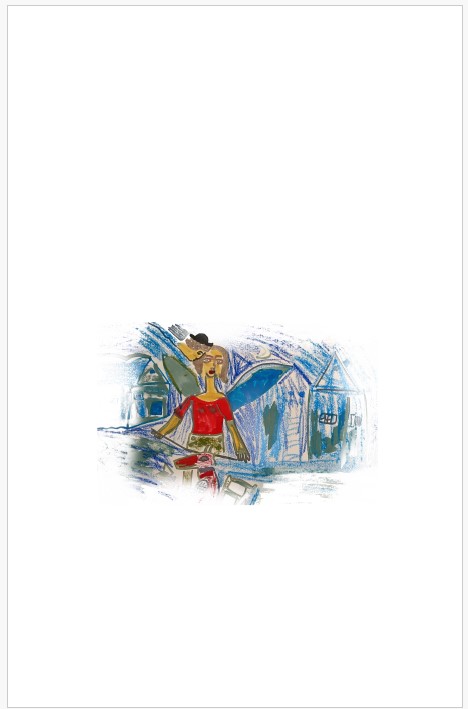

In our artistic-scientific work in the PEEK/ FWF project Confronting Realities. Working on cinematic autosociobiographies, I focus on the role of the family in the formation and transmission of autosociobiographical narratives. In film labs (LAFA) we collectively explore autosociobiographies.

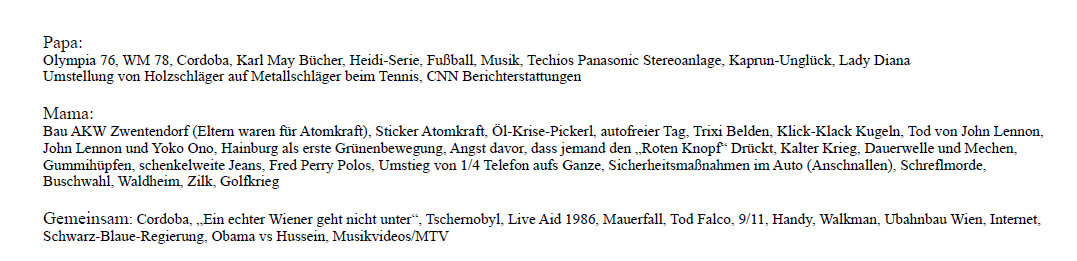

The first film lab 2022 was dedicated to the mother, the second lab 2023 to the father and the third lab 2023/2024 to siblings & chosen family.

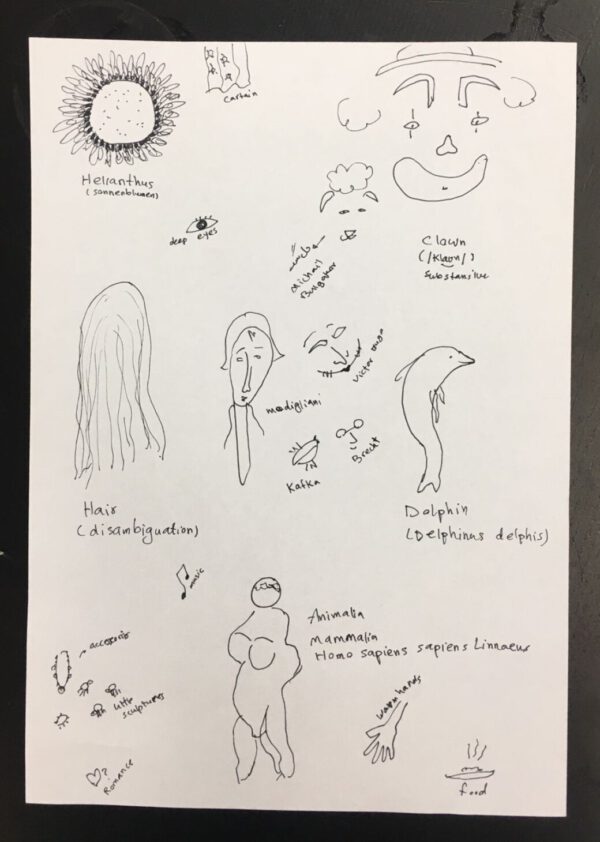

Literary works such as Wunschloses Unglück by Peter Handke (1972), Une Femme (1987) and L’événement (2000) by Annie Ernaux, Combats et métamorphoses d’une femme by Édouard Louis (2021), Man kann Müttern nicht trauen by Andrea Roedig (2022) and Eine Arbeiterin. Leben, Alter und Sterben by Didier Eribon (2024) as well as films such as Les Années Super-8 by David Ernaux-Briot and Annie Ernaux (2022), Retour à Reims (Fragments) by Jean-Gabriel Périot (2021), L’événement by Audrey Diwan (2021) and Alle reden übers Wetter by Annika Pinske (2022), together with Negin Rezaie, Nasima, Robin Jentys, William Joop, Caspar Thiel and Christina Wintersteiger-Wilplinger to trace the connecting and intersecting lines of families and their children as well as their life paths. From a genealogical perspective, we explored the places, times, bodies, social classes, sexuality, educational and work biographies and ages of our mothers/fathers/siblings/chosen family and examined them using artistic and scientific methods of exploration, translation, reflection and re-iteration.

By combining various artistic autosociobiographical elements of this autosociobiographical exploration, we ultimately ask for a cinematic autosociobiographical translation and representation of these relations.

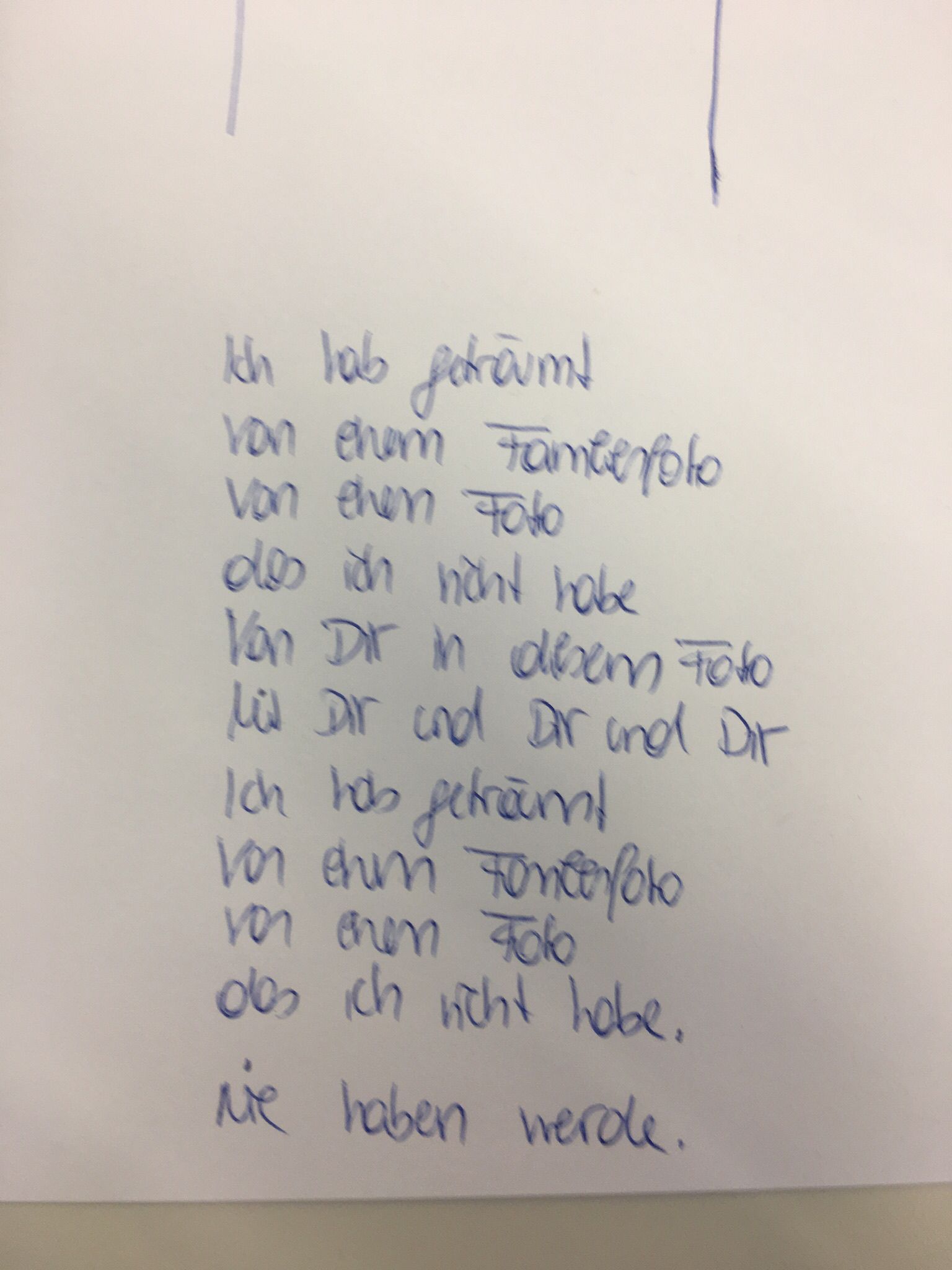

The Digital Archive (DAFA) is the archiving of our exploration processes. It is intended to make the artistic exploration process as well as the connections of a collective artistic-scientific work visible and to provide impulses for visitors for their own autosociobiographical exploration. These impulses are freely available, they are there to make something oscillate, to find an impulse for an artistic translation, to go further on the topic of family in terms of autosociobiography. They are impulses between you and your mother/mothers, your father/fathers, your siblings. Or not.

“The “psychological” power of family ties is above all a social one: it is largely based on the fact that the structures of the social world are inscribed in individuals and their brains from earliest childhood. It is also based on the countless social invocations and rituals that contribute to perpetuating not necessarily a sense of familial affection, but at least a sense of familial belonging, with all the obligations that entails. No matter how hard we try to keep our own family at a distance, no matter how much we want to distance ourselves from it and free ourselves from its grasp, we are always thrown back on it by an ensemble of constraints, constraints that have all the greater power over us because they come in the form of ritualized feelings and obligations. Pierre Bourdieu described the two opposing forces at work in the family very aptly in a famous article: the centripetal force and the centrifugal force, the family as a “body” and as a “field”, as a place of fusion and fission[1].”

Didier Eribon, A Worker. Life, old age and death (2024), p.140

“I had the impression that the dictionary was one of the few documents that could provide me with information about my mother, as if I could find excerpts from personal documents in it, as a substitute for a non-existent family archive. Fragments of her life story, so to speak. Of course, I would have liked to have been given a book like the one Danilo Kiš imagines in his “Encyclopaedia of the Dead”. In it, the narrator is taken to a library where she comes across countless volumes full of biographies of deceased people who – according to the condition – have only been included in the work because they are not famous and therefore do not appear in any other encyclopaedia. The detailed articles about these unknown people are remarkable in that they describe all the “human relationships, encounters and landscapes” as well as “the multitude of details that make up a human life”. Every gesture, every thought, all the songs that were hummed in youth: “Nothing has been left out.” Historical and political events are only mentioned insofar as they are “linked to personal destiny”, because for the authors of the encyclopaedia, “every human being is a sanctuary”. The narrator immerses herself in her father’s life, about which she does not know much. Everything is recorded there, every place he has ever been, every moment of his life, every event, no matter how big or small. Even his hospitalization and death … She writes everything down, “as much information as possible […] to have proof in hours of despair that his life had not been superfluous, that there are still people in the world who record and cherish every life, every suffering, every human existence” [2]. How I would love to read such an encyclopedia entry about my mother! About my father too. About simple people like her, whose life stories are rarely told.”

Didier Eribon, A Worker. Life, old age and death (2024), p.163&164

“Instead, she wants to document her stay on earth, in a given era, the years that have passed through her, the world that she has stored in herself simply by having lived. This is why she draws the intuition for the form her book should take from another feeling, a feeling that comes over her when, based on an image of the past – how she lies in hospital after the war alongside other children who have had their tonsils out, how she travels through Paris by bus in July 68 – she has the impression of being absorbed into something larger, a blurred whole whose individual components – customs, actions, words, etc. – she can bring to light through an act of her critical consciousness. In this way, the tiny moment of the past becomes larger and larger, it becomes a horizon that is mobile but also has a uniform tonality, the horizon of one or more years. Then she is overcome with a deep, almost overwhelming satisfaction – which she does not feel in the face of the individual image, the personal memory – a comprehensive feeling for society, in which her consciousness, indeed her whole being, is contained.”

Annie Ernaux, The Years (2008), p. 251

“The form of her book can therefore only emerge when she immerses herself in her own memory images and looks at the characteristics of the era or the respective year from which they roughly originate – when she gradually brings them together with other images, recalls what people said, how they commented on events and things, when she picks out her words from the mass of communications, from the background noise that constantly formulates how we should be, what we should think, believe, fear, hope. She wants to reconstruct a social time from the imprint that the world has left on her and her contemporaries, a time that began a long time ago and continues to this day – she wants to find the memory of the collective memory in an individual memory and thus fill history with life. The book is not intended to be what is usually understood by memory work, which is about retelling and explaining a life. She only looks inside herself to find the world, the memory and the dreams of the past, to grasp how ideas, beliefs and feelings, how people and the subject have changed, changes that she herself has witnessed and which are perhaps nothing compared to those that her granddaughter and the people of 2070 will have experienced. To trace feelings that are there but do not yet have a name, like the feeling that inspires her to write.”

Annie Ernaux, The Years (2008), p. 253

“The book to be written would be her contribution to the revolt. She has not abandoned this intention, but in the meantime it is more important to her to capture the light that falls on faces that are now invisible, on tablecloths with food that has disappeared, a light that was already there in the stories of her childhood, at Sunday family dinners, and that has since shone on everything she has experienced, an earlier light. To be saved (…)”

Annie Ernaux, The Years (2008), p. 254

Saving something of the time you will never be in again.

Annie Ernaux, The Years (2008), p. 255

[1] Pierre Bourdieu, »Àpropos de la famille comme catégorie réalisée«, in: Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales (1993), S. 32-36.

[2] Danilo Kiš, »Enzyklopädie der Toten« (1981), in: ders., Enzyklopädie der Toten, aus dem Serbokroatischen von Ivan Invanji, München: Hanser 1986, S. 45-75.

Table of Contents