FAMILY HISTORIES

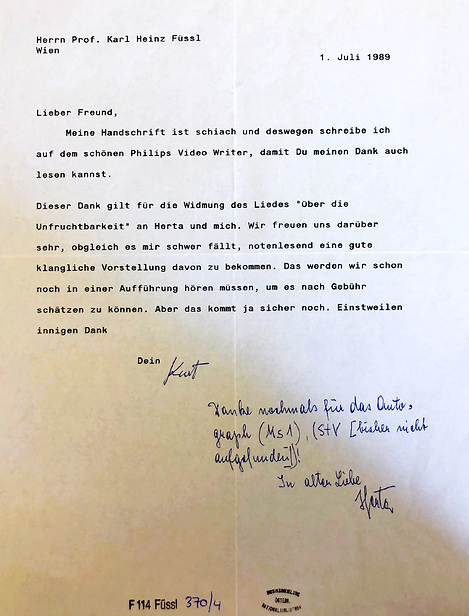

In all likelihood, Herta Singer and Kurt Blaukopf first met in 1948 while working on the editorial staff of the Austrian newspaper “Der Abend” (cf. Blaukopf, K. 1998: 21-49). From that moment onward, a life-long intellectual relationship started to develop between the two scholars, who only became romantically involved years later. Following their marriage in 1959, their son, Michael Blaukopf, was born in 1962 (cf. Seiler 2018: 88). However, the successful nature of their research partnership and scientific collaboration, which they managed to continue and intensify throughout their lifetimes, certainly is to be viewed against the backdrop of biographical similarities, shared experiences and suffering (cf. Reitsamer 2019, Chaker/Viehböck [forthcoming]).

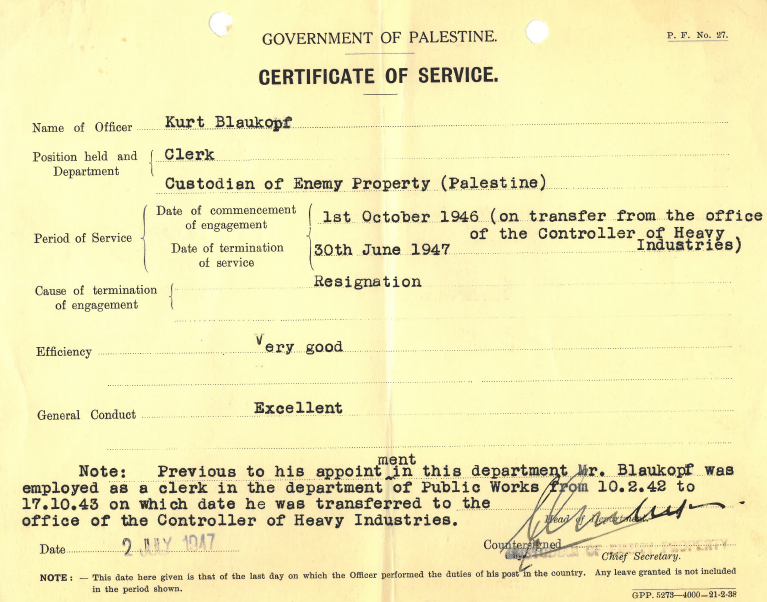

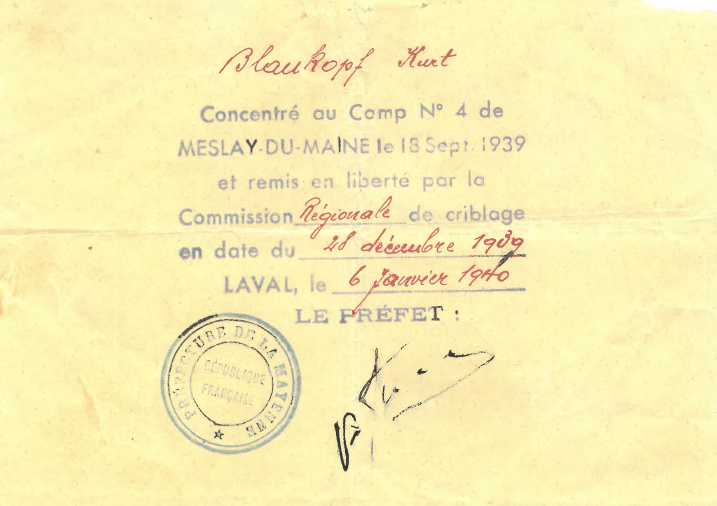

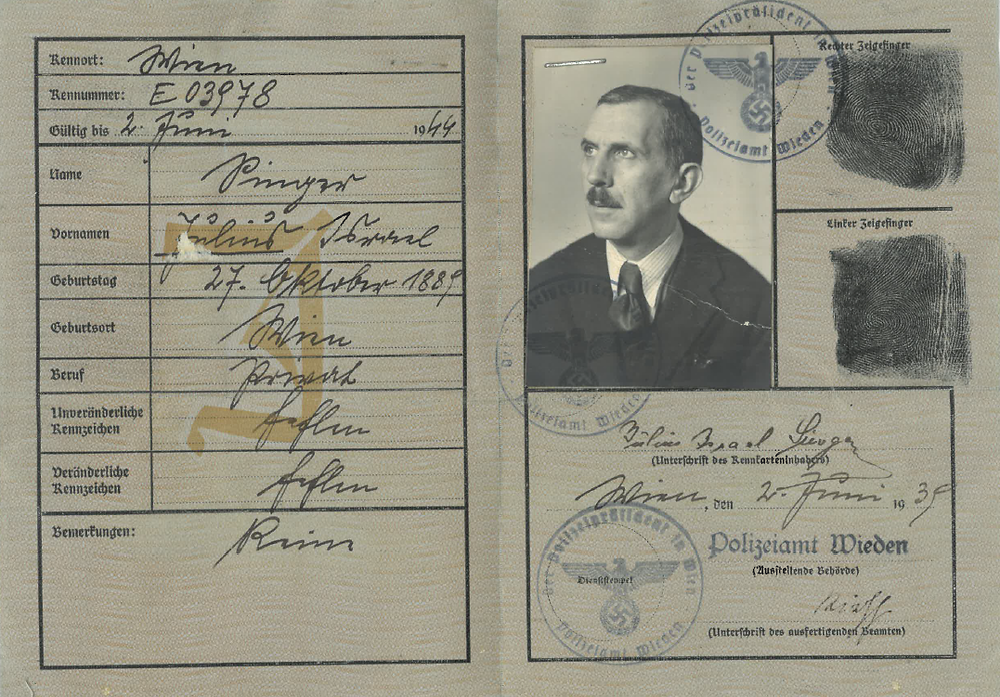

First and foremost, it must be pointed out that both Herta Singer’s and Kurt Blaukopf’s lives were severely affected by numerous instances of antisemitic discrimination motivated by the rise of National Socialism from the 1930s onwards. Since both of them had Jewish ancestry, they became victims of the repressive politics and violence instigated by the Nazi regime (cf. Reitsamer 2019: 1-2). Herta Singer, for instance, was denied a continuous education. While she was forced to change schools repeatedly during her teenage years, she was ultimately banned from higher education altogether and had to wait for the Second World War to end in order to study at university (cf. Seiler 2018: 89). During the war, her piano teacher, Olga Novakovic, introduced her to a number of central figures pertaining to the so called “Schönberg-Schule”, who had gone into hiding in order to avoid persecution. Some of them, such as Anton von Webern, but also others such as the clarinettist and composer Friedrich Wildgans, secretly gave lectures on music theory that Herta Singer would attend. However, also her family helped some of their relatives to go underground and even hid Herta’s aunt in their own home (cf. Göllner 2002). Kurt Blaukopf, on the other hand, was arrested in 1937 and kept imprisoned for several weeks. While he was never officially informed about the reason for his detainment, he suspected it to be linked to his aiding incarcerated members of the organisation “Republikanischer Schutzbund” and their families (Blaukopf, K. 1998: 21). In 1938, Kurt Blaukopf managed to flee to France, where he was interred in a camp near Meslay-du-Maine by the beginning of the war. Two years later, he succeeded in obtaining a visa for Jerusalem, while his parents and brother were able to emigrate to the United States via Portugal. Unlike his family, who fully broke their ties to Austria due to their traumatising experiences within the National Socialist regime, Kurt Blaukopf returned to Vienna in 1947 in order to participate in rebuilding the country’s intellectual life and scientific institutions (ibid.: 21-49) – a vision that was also shared by Herta Singer.

Besides their suffering caused by antisemitic repression, violence and war experiences, the individual biographies of the two scholars also share other elements that facilitated the successful development of their long-term research partnership (cf. Reitamer 2019, Chaker/Viehböck [forthcoming]). Coming from (upper) middle-class backgrounds, Herta Singer and Kurt Blaukopf experienced similar upbringings and socialisation rituals, particularly with respect to music: Both were well versed in the realm of classical music (regarding theoretical knowledge as well as practical skill) and entertained contacts to a vast network of international artists and creatives throughout their entire lifetime. For instance, Richard Fränkel, Herta Singer’s grandfather, was head of the social-democratic “Arbeitersängerbund” (cf. Seiler 2018: 90), while Kurt Blaukopf’s mother, Anna Blaukopf (née Tropp) performed as a professional pianist (cf. Blaukopf, K. 1998: 43). In addition, the Blaukopf family also participated in the salon-culture of the time and frequently organized events that brought together illustrious figures such as writers, actors and actresses or musicians, including the renowned Kolisch-Quartett (cf. Blaukopf, K. 1998: 14). Consequently, both Herta Singer’s and Kurt Blaukopf’s families can be located within the intellectual circles of the upper-middle-classes. However, the Singer family in particular tried to share their liberal-democratic ideals with society and actively participated in the political system: Herta Singer’s grandfather as well as her parents, Julius and Anna Singer (née Fränkel), were committed social democrats and long-term members of the “Sozialistische Partei Österreichs”.

Sources

Blaukopf, Kurt: Unterwegs zur Musiksoziologie: Auf der Suche nach Heimat und Standort, Graz/Wien 1998.

Chaker, Sarah/Viehböck, Raphaela: „Miteinander gearbeitet haben wir, seit wir einander kannten“. Zur wissenschaftlichen Partner*innenschaft von Herta und Kurt Blaukopf, in Fornoff-Petrowski, Christine/Bagge, Maren/Ricke, Anna/Rode-Breymann, Susanne (Hg.): (Wahl-)Verwandtschaften: Gemeinschaftliches kulturelles Handeln. Böhlau Verlag (forthcoming).

Göllner, Renate: Leben und Überleben im Dritten Reich. Ein Gespräch mit Herta Blaukopf über das unterirdische Fortwirken der Schönberg-Schule, in: Zwischenwelt. Zeitschrift für Kultur des Exils und des Widerstands 19/2 (2002), S.13-18.

Reitsamer, Rosa: Presentation given at the first award ceremony for the Herta and Kurt Blaukopf Award for outstanding dissertations at the mdw – University of Music and Performing Arts Vienna, 16 December 2019.

Seiler, Martin: Blaukopf, Herta, geb. Singer, in: Korotin, Ilse/Stupnicki, Nastasja (Hg.): Biografien bedeutender österreichischer Wissenschafterinnen, Wien 2018, S. 88-95.