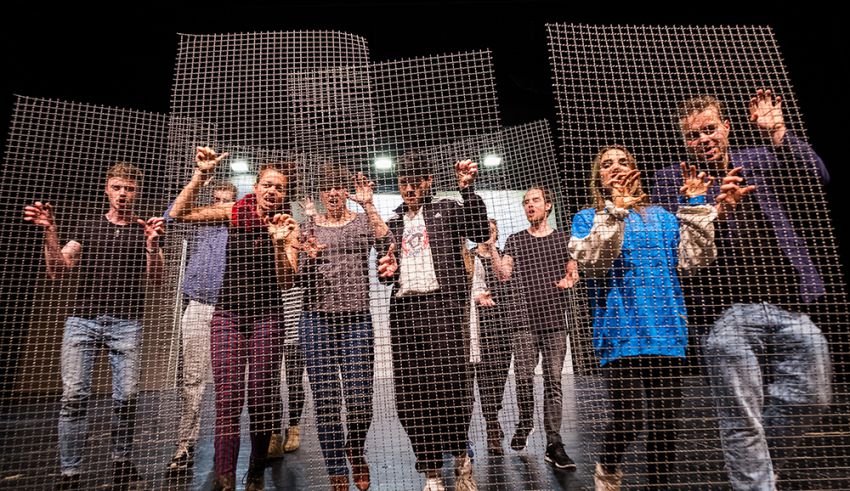

“In Wahrheit ist’s ne Lüge” is going to premiere in Schönbrunn Castle Theatre on 17 May 2017.

Plays with songs in them have a long tradition. This is not something exclusive to Vienna, but thanks to Nestroy, it is something of a Viennese speciality.

What’s more, today’s theatrical world in general is demanding better and better singing skills from actors. Consequently, training in music joins role coaching, speech, and physical training as the fourth pillar of the Max Reinhardt Seminar’s acting programme. Students are offered seven semesters of voice training and singing instruction, areas that collaborate closely with speech and physical training to form the basis of a young actor’s vocal functionality. The second year of practical musical training includes individual song interpretation lessons, which merge into preparation of a staged recital during the third year.

The focus here is on developing the ability to interpret songs on one’s own. And there are also many things to be learned here that can support actors in all aspects of their professional work later on. The way we work on songs makes this clear:

Our priority is to tell a story. For this reason, we start with the lyrics. In much the same way as it happens with one’s lines in role coaching sessions, lyrics get taken apart, put back together, kneaded, and chewed on until they unfold naturally in speech. This is a both intellectual and associative process.

Next, we listen to the music, experiencing its narrative of moods, tone colours, tensions, and rhythms. This frequently seems to contradict the work done on the lyrics, which is precisely why putting together the language and the music gives rise to the kind of tension that makes this kind of work so special: the music and the lyrics, after all, have their own respective rhythms and their own respective melodies—and these wrestle to be heard. If the music wins, the thoughts behind the song take a back seat to the overall whole. But when the text’s rhythm and melody are clear to be heard, the narrative becomes well-grounded and direct.

Smoothly flowing back and forth between the rhythms and melodies of both the lyrics and the music transforms a piece of music with verbal content into a musically intensified narrative. This back-and-forth between priorities is essential, since it allows actors to arrive at an interpretation that builds on their personal qualities while also rendering their differing musical talents less important.

But this, of course, is also frequently the most difficult aspect: switching over from a song’s rhythm to the free rhythm of prose can sometimes seem a bit like attempting to yank the thin tyres of a racing bike out of a tram track groove. After all, by the time you attempt it, you’re thoroughly in the groove. This groove—which is to say: rhythm—is often something of a stepchild, in our case. But being rhythmically assured means physically internalising the beat, feeling the body’s impulsive answer to a rhythm, and not letting go of it. And then placing the rhythmic motifs of the melody and the lyrics on top of that.

A basic prerequisite for all this is something that I consider this work’s greatest adventure: listening. Listening means taking a break from the world we normally inhabit, in which our students’ existence is dominated by urges to create, to show one’s personalities, to make progress, and to rush from one lesson to the next…

Those who listen are in the here and now. Neither a tenth of a second before, nor already in the next sentence. To listen is to flow. And this flow is something unfamiliar, unstable: it means letting go, jumping in, losing control, giving oneself over. Listening is the most important thing.

As listeners, we go onstage to experience something. After all, if we wanted to get something across, this intention would insert itself between us and the moment like a glass wall. It does seem paradoxical, though, to want to experience something when we know both that it will happen and (for the most part) how it will happen.

Music is immanently suited to learning how to deal with this paradox: it’s a way to passively experience something that one does actively without becoming a distant observer. This is so because the spiritual and emotional experience of music-making is so strong and direct. Shaping one’s interpretation takes place beforehand. Once we hit the stage, it’s all about experiencing. We teach singing with help from the Indian system of solmisation known as sargam, which is easy to grasp in its basic elements and trains both the ear and one’s temperament in a very special way.

There are, of course, many musical elements that have to be worked out: phrasing, how one’s breathing is shaped, dynamics. But at this point, many things become clear thanks to the work one has already done. Connecting them with the actor as a person is the next step. In order to bring out our young actors’ very own perspectives on a song’s themes, we employ relaxation and visualisation techniques derived from autogenic training. Here, they find an authentic, direct, personal, and perhaps even archetypical approach to their songs, an approach that draws on very different sources than before.

It is following all this that the work to put it onstage begins…

In the course Musikalische Rollengestaltung [Musical Role Coaching], this process is expanded to encompass work in a group. Choir rehearsals with plenty of rhythmic trance-based work create that “more than the sum of its parts” that is theatre, the ensemble, and the resonance amplifier of meaning that arises from contextualisation: themes relevant to our times form the nutrient solution that feeds performances of songs and entire scenes, even if they seem to have nothing to do with each other thematically. Formally, such themes create structure and friction: for instance, last year’s migration of refugees along with touching attempts to come to terms with the topic of entropy and, formally, with that of the alternation between chaos and order. And this year, we will be using the play In Wahrheit ist’s ne Lüge [In Truth, It’s a Lie] to grapple with the inscrutability of information in the information age. All this then comes back to form the framework and backdrop for the actors when they go onstage and sing Nestroy’s famous lyrics: “Die Welt steht auf kein’ Fall mehr lang, lang, lang, lang.” [This world surely won’t be around for long, long, long, long.]

Information about the current piece.

- Find information about current productions as well as all representation dates on the website of the Max Reinhardt Seminar.