„Künstlerehe. Suche behufs Ehe Bekanntschaft mit […] Sängerin.“ Kontaktanzeigen beschränken sich immer auf das Notwendigste, und so formulierte 1903 ein Künstler sehr knapp, was er sich von seiner Zukünftigen erhoffte, nämlich eine Künstlerehe. Es ist nicht die einzige Anzeige, die im Neuen Wiener Tagblatt erschien, und der Heiratswillige konnte außerdem darauf vertrauen, dass das Modell der Künstler- oder Musikerehe nicht weiter erklärungsbedürftig sei: Nicht erst seit den Ehepaaren Hasse und Bordoni, Lebrun und Spohr, seit Marìa Malibran und Charles de Bèriot, Clara und Robert Schumann, Joseph und Amalie Joachim, den Ehepaaren Jaëll und von Bronsart, Teresa Carreño und Eugen d’Albert, den Sängerpaaren Vogl, Schnorr von Carolsfeld und zahllosen anderen waren Künstlerehen auch in der Musik eine häufige Erscheinung.

Dieser Befund stand zu Beginn des Forschungsprojekts Paare und Partnerschaftskonzepte in der Musikkultur des 19. Jahrhunderts: Musikerehen sind nicht die Ausnahme, sondern eine quantitativ auffällige Erscheinung. Hinter dem Vorhang des eheuntauglichen, vom Liebesglück gemiedenen oder allenfalls mit einer Muse liierten Genies, das die musikhistoriografische Wahrnehmung auf Einzelpersonen lange dominiert hat, standen (und stehen bis heute) eine Vielzahl von Ehepaaren und künstlerischen Partnerschaften, oft sogar über mehrere Generationen hinweg: Marianne Tromlitz etwa, aus einer Musikerfamilie stammend und als Sängerin und Pianistin tätig, heiratete (in erster Ehe) den Klavierpädagogen Friedrich Wieck, die gemeinsame Tochter Clara fand später in Robert Schumann ihren Ehemann. Auch Tromlitz’ zweite Ehe nach der Scheidung von Friedrich Wieck war übrigens eine Musikerehe. Der Kombination verschiedener Professionen innerhalb der Musikerehen waren dabei kaum Grenzen gesetzt: Pianistinnen waren mit Kapellmeistern verheiratet, Komponisten oder Musikschriftsteller mit Sängerinnen, Musikwissenschaftler mit Pianistinnen, Intendanten mit Komponistinnen, Pädagogen mit Librettistinnen, Virtuosinnen mit Virtuosen, Sängerinnen mit Sängern … Die Verheiratung innerhalb des Berufsfelds Musik war, wie in anderen Berufen auch, durchaus von Vorteil: gemeinsames Reisen und Auftreten bei Bühnenberufen, gemeinsame Werkstätten im Instrumentenbau und -handel, ähnliche berufliche Herausforderungen, Karriereplanungen und Schwierigkeiten, ähnliche Netzwerke und Freundeskreise, bestenfalls ästhetische Geistesverwandtschaft.

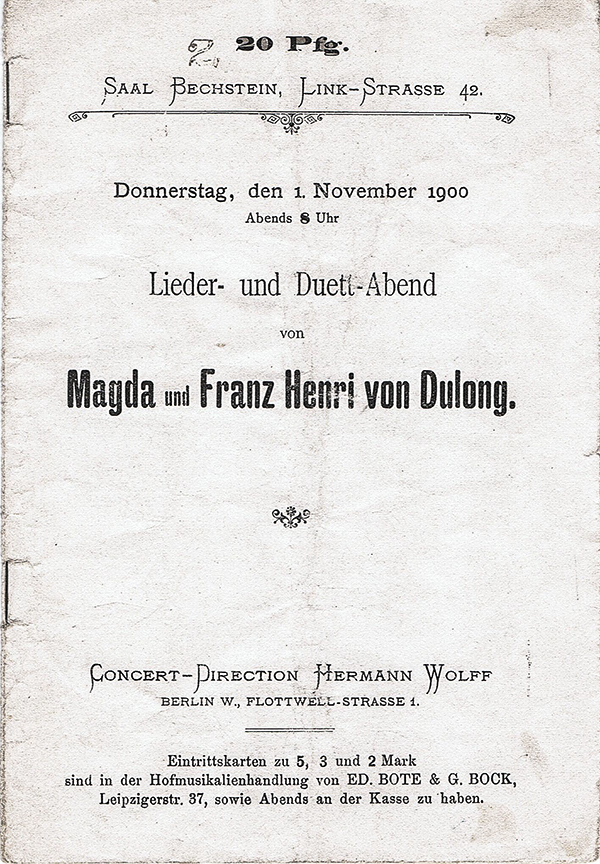

Eine solche Vielzahl und Vielfalt an Musikerehen war im 19. Jahrhundert nicht neu, denn auch zuvor sind innerhalb der Musikerfamilien die Teilhabe beider Ehepartner an der Musikprofession belegt: Musikerfamilien wie die Couperins oder Jacquets in Frankreich, oder auch die Bach-Familie, Stamitz, Danzi, Duschek, Lebrun, Cannabich, Wendling u. v. a. m. wären hier zu nennen. Neu aber war im 19. Jahrhundert zum einen, dass das bürgerliche Familienmodell die Geschlechterrollen der Ehepartner stärker auf eine Geschlechterpolarität zuschnitt, und zum anderen die Idee der Liebesheirat: Liebe als unbedingte emotionale Übereinstimmung zwischen zwei Menschen löste das Prinzip einer Versorgungsheirat ab. Musikerpaare standen damit vor einer neuen Herausforderung: Es galt nicht nur, eine professionelle Passgenauigkeit zu wählen, sondern sich als ideales Liebes-, Ehe- und Künstlerpaar zu finden, sich vor allem auch öffentlich als solches zu inszenieren. Die Presse der Zeit gibt immer wieder Hinweise darauf, dass die Harmonie in Liebe und Ehe gemeinsam mit einer künstlerischeren Passgenauigkeit wahrgenommen wurde: Gemeinsame Auftritte des Geigers Louis Spohr und seiner Ehefrau, der Harfenistin Dorette Spohr, wurden als „vollkommenste harmonische Vermählung des vortrefflichen Künstler-Paars“ beschrieben. Auch Sängerpaare wie Magda und Franz Henri von Dulong machten das gemeinsame Auftreten zum eigenen Markenkern (siehe Abb. Programmheft S. 16). Hans von Bülow nannte Therese und Heinrich Vogl wiederum ein „unvergleichliches Künstlerpaar“, und nachdem die beiden unter Bülows Leitung in München als Tristan und Isolde aufgetreten waren, veröffentlichte der Münchner Wagner-Verein 1872 ein Huldigungsgedicht („Heil dem edlen, echten Künstlerpaar …“) (siehe Abb. Ehepaar Vogl S. 18). Dass das Ehepaar Vogl auf der Bühne freilich das ehebrechende Liebespaar Tristan und Isolde verkörperte, stand für das Publikum keineswegs im Widerspruch zu den geltenden moralischen Vorstellungen: Der Ehebruch, wie er auf der Bühne als Hymnus an die Liebe zelebriert wurde, war im Gegenteil durch die Darstellung des idealen Sängerehepaares geradezu befriedet.

Einer solchen Idealisierung der Partnerschaft, die einen emphatischen Liebesbegriff mit den Konventionen bürgerlicher Ehevorstellungen zu verbinden versuchte, hielten freilich zahlreiche Realitäten kaum Stand. Tatsächlich stellte die Frage des bürgerlichen Familienideals und einer Künstlerkarriere für beide Ehepartner die Musikerpaare vor enorme Herausforderungen. Egodokumente wie Briefe oder (Ehe-)Tagebücher zeugen immer wieder von den oft schwierigen Aushandlungsprozessen einer künstlerischen Partnerschaft auf Augenhöhe: „Das erste Jahr unserer Ehe sollst Du die Künstlerin vergeßen, sollst nichts als Dir u. Deinem Haus und Deinem Mann leben […]. Das Weib steht doch höher als die Künstlerin, und erreiche ich nur das, daß Du gar nichts mehr mit der Oeffentlichkeit zu thun hättest, so wäre mein innigster Wunsch erreicht“, schrieb etwa Robert Schumann seiner als Pianistin erfolgreichen, essenziell auch für den Lebensunterhalt der Familie sorgenden Ehefrau Clara Schumann. Von solchen Sollbruchstellen zeugen die Quellen immer wieder: Abbruch von Karrieren, Änderungen der Karrierestrategien oder gar der Profession, Um-Definition von Erfolg/Misserfolg, das Austarieren der Rollen von Solo/Begleitung, Interpretation/ Komposition u. a. m.

Darüber hinaus waren auch Sollbruchstellen in den Vorstellungen von Künstlersubjekt und bürgerlicher Ehe unübersehbar: Erstere war geprägt von männlicher Autonomie (was sowohl gegen eine Heirat des Künstlers als auch gegen eine Künstlerschaft der Frau sprach), Letztere von moralisch enggefassten Geschlechterrollen. Entsprechend kamen neben den emphatischen Manifestationen des Ideals vom Künstler- und Liebespaar immer wieder auch kritische Stimmen zu Wort. In Alphonse Daudets enorm populären Novellenband Künstlerehen (franz. Original: Les Femmes d’artistes, 1878), der in Deutschland bis 1926 knapp 20 Auflagen erreichte, zerbrach jede dieser Partnerschaften. Und um 1900 wurden mehrere Umfragen veröffentlicht („Ehen unter Künstlern. Eine Rundfrage bei Theaterleuten“ oder „Sollen Künstlerinnen heiraten?“), in denen mit ähnlicher Skepsis kontrovers über die Künstlerehe diskutiert wurde. So unterschiedlich die Antworten zu diesen Umfragen ausfielen – von der klaren Ablehnung der Künstlerehe bis zur selbstverständlichen Anerkennung – ist die enge Verzahnung vom Künstlerehediskurs und dem Diskurs um das bürgerliche Geschlechter- beziehungsweise Ehemodell unübersehbar, kulminierend in der Frage der Vereinbarkeit des Künstlerinnenberufs mit dem bürgerlichen Familienleben. Die Opernsängerin Paula Doenges wird mit dieser Problematik als Gegnerin der Künstlerehe zitiert: „Im Prinzip sage ich ‚Nein‘. Denn der größte Wirkungskreis der verheirateten Frau, Mutter und Hausfrau zu sein, ist für uns leider sehr schwer zu erfüllen.“ Dagegen hob Marie Wittich, ebenfalls Sängerin und als Uraufführungs-Salome durchaus mit antibürgerlichen Weiblichkeitskonzepten vertraut, die ergänzende Wirkung dieser beiden Bereiche hervor, es entstehe „eine Wechselwirkung zwischen Beruf und Häuslichkeit, die für alle Beteiligten von größtem Segen begleitet sein kann“.

Das Forschungsprojekt Paare und Partnerschaftskonzepte in der Musikkultur des 19. Jahrhunderts, das seit 2016 an der mdw beheimatet ist, nimmt den Diskurs um die Musikerehe in den Blick: das Konzept der bürgerlichen Ehe und das der Liebesheirat, das sich mit künstlerischer Partnerschaft verschränkt, oder an dieser Verschränkung scheitert. Denn so einfach, wie es (selbst) die (Forschungs-)Literatur lange aufgezeigt hat – er Genie, sie Muse –, ist es in keinem der zahlreichen Fälle von Musikerehen. Zahlreiche Egodokumente von Musikerpaaren werden dazu ausgewertet und mit Quellen in Beziehung gesetzt, die die öffentliche Auseinandersetzung über Musikerehen beleuchten: Zeitungsartikel, Novellen, wissenschaftliche Abhandlungen, visuelle Quellen, Repertoirebücher, Kompositionen, die Musikerpaaren gewidmet sind oder die für das Paar-Repertoire komponiert wurden, Opern, die Musikerpaare als Sujet verhandeln, u. v. m. Denn das Künstlerpaar, so harmonisch es in der Idealisierung der bürgerlichen Idee war – „Es war keine glücklichere, keine harmonischere Vereinigung in der Kunstwelt denkbar, als die des erfindenden Mannes mit der ausübenden Gattin“ (La Mara über das Ehepaar Schumann) –, blieb dennoch eine stete Herausforderung und Konfrontation des bürgerlichen Selbstverständnisses mit den künstlerischen Interessen von Musikerinnen und Musikern.