Repertoire, Interpretation and Meaning

Andrés Cea Galán

How to cite

How to cite

Abstract

Abstract

Antonio de Cabezón (1510–1566), as a musician in the service of the Spanish royal court, held a really prominent position that allowed him to come into contact with musicans and players of very diverse origins, not only in Spain but also in Italy, Austria, Germany, the Netherlands and England. In this paper, an overview of his work is presented in the context of European music of his time, together with comments on aspects of the interpretation and meaning of this repertory in the light of historical sources.

About the Author

About the Author

Organist, musicologist, educator and editor, Andrés Cea Galan studied in Spain, France and at the Schola Cantorum Basiliensis. He completed his doctorate at Madrid Complutense University with a dissertation on Spanish keyboard tablatures. His books and articles are devoted to the performance of Spanish music as well as to the history and aesthetics of the organ in Spain. As a music editor, he has published the music of Francisco Fernández Palero, Sebastián Raval and Juan Cabanilles, among others. As a performer, he is frequently invited to play concerts all around Europe, México, South-America and Japan, and has also been invited to lecture and teach by international academic institutions. He has recorded for Lindoro, Almaviva, Tritó, Aeolus and Universal labels. He is the president of the Instituto del Órgano Hispano (www.institutodelorganohispano.es).

Bive agora Antonio el ciego, tañedor de la Capilla de la Emperatriz, que en el arte no se puede más exmerar, porque dicen que [ha] hallado el centro en el componer.1

This article aims to offer an overview of Antonio de Cabezón’s music in the European context of his time. Before entering into the relevant aspects of his compositional output, it is necessary to review an important part of Cabezón’s life. Only then can any guidelines for the interpretation of his music be presented in light of the most recent research.

As a point of departure, let us consider the words contained in the preface to Obras de música, published by Antonio’s son, Hernando, in 1578:2

And no one was so mad as to not surrender their fantasies to the renowned genius of Antonio de Cabezón. This was understood not only in Spain, but also in Flanders and Italy, where he journeyed in the service of our lord the Catholic Monarch King Philip.3

Evidently, this passage seeks to express the importance and singular nature of Antonio de Cabezón as a composer and performer in the European context of his time. Though this description may seem an exaggeration to us, one must bear in mind that during his lifetime, Antonio de Cabezón stood at the centre of the world.

It bears emphasising that Antonio de Cabezón served as a musician in the Spanish Royal Court over the span of 40 years, beginning in 1526 at the age of 16 and continuing uninterrupted until his death in 1566.4 During this period, he was in turn in the service of the members of the royal family listed in Tab. 1.

| Tab. 1: Antonio de Cabezón (1510–66) in the service of the Spanish Royal Court | |

|---|---|

| 1526–39 | Empress Isabel of Portugal |

| 1539–48 |

Infantas (princesses) Juana and María, and Prince Philip, |

| 1548–56 | Prince (later King) Philip II |

| 1557–59 | Prince Carlos (son of Philip II) |

| 1559–66 | King Philip II |

Empress Isabel of Portugal was the wife of the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, grandson of Maximilian I of Habsburg. Isabel acted as regent in the Spanish territories during the long absences of her husband, whose involvement in state affairs required extensive travel. Following the death of the empress in 1539, Cabezón went into the service of her daughters Juana and María of Austria.

María of Austria married Maximilian II of Austria in 1548. Together they succeeded the Empress Isabel as regents in Castille during the continued absences of the emperor, now often accompanied by his own son, Prince Philip. Maximilian and María left Spain in 1552 for his native Vienna. Following the death of Maximilian in 1576, María returned to Madrid and retired to the convent of Las Descalzas Reales, an institution founded in 1577 by her sister Juana. Among her retinue there, serving as a chaplain, was the composer Tomás Luis de Victoria. Though now relegated to the role of dowager empress, given her status as the widow of Emperor Maximilian, two of her sons, Rudolf and Matthias, would both eventually secure their own election to the imperial throne.5 Furthermore, María was mother of two rulers of the Low Countries (Ernest and Albert of Austria),6 as well as mother of Maximilian III, regent of Austria. María’s daughter Elisabeth became queen of France by marriage7 and her daughter Ana married her own uncle, Prince Philip, after his accession to the Spanish throne as Philip II.

María of Austria’s younger sister, Juana, married King Joâo Manuel of Portugal. Their son would later succeed to the Portuguese throne as Sebastiâo I. Following the death of her husband in 1554, she returned to Spain and assumed a regency for the duration of her brother Philip II’s voyage to England to marry Mary Tudor.

Throughout this period, the Spanish court had no fixed residence. As a court musician, Cabezón’s travels therefore took him across Europe, where he passed through the many cities listed in Tab. 2.

| Tab. 2: Cities in which Antonio de Cabezón’s music sounded |

|---|

| 1. SPANISH CITIES WHERE ANTONIO DE CABEZÓN LIVED WITH THE COURT |

| Valladolid, Palencia, Burgos, Toledo, Segovia, Avila, Salamanca, Zamora, Badajoz, Burgo de Osma, Medina del Campo, Tordesillas, Alcalá de Henares, Madrid, Lerma, Arévalo, Aranda de Duero, Ocaña, Aranjuez, El Pardo, Torquemada, Villalón, Monzón, Zaragoza, Barcelona or Valencia, among many others. |

| 2. THE ITINERARY WITH PRINCE PHILIP TO BRUSSELS |

| Valladolid (2th October 1548), Zaragoza, Barcelona |

| Genoa (25th November 1548), Alessandria, Pavia, Milano, Malegnano, Lodi, Cremona, Mantova, Villafranca, Rovereto, Trent, Bolzano, Brixen |

| Innsbruck (4th February 1549), Munich, Augsburg, Ulm, Heidelberg, Saarbrücken, Luxemburg, Namur |

| Brussels (1st of March 1549–12th July 1549) |

| 3. CITIES VISITED IN THE LOW COUNTRIES WITH PRINCE PHILIP |

| Lovain, Dendermonde, Gant, Brugge, Ypres, Bergues, St. Omer, Bethune, Lille, Tournai, Douai, Bapaume, Cambrai, Valenciennes, Le Quesnoy, Binche, Mons, Soignies, Malines, Lier, Amberes, Bergen op Zoom, ‘s-Hertogenbosch, Gorinchem, Dordrecht, Rotterdam, Delft, ‘s-Gravenhage, Leiden, Haarlem, Amsterdam, Utrecht, Amersfoort, Harderwijk, Campen, Zwolle, Deventer, Zutphen, Arnhem, Nijmegen, Middelaar, Venlo, Roermond, Weert and Turnhout, among other cities along the way. |

| 4. ITINERARY OF THE RETURN TO SPAIN WITH PRINCE PHILIP |

| Brussels (26th October 1549–7th June 1550), Aachen, Köln, Augsburg (8th July 1550–25th May 1551), Genoa, Barcelona (12th July 1551) |

| 5. TRIP TO ENGLAND WITH PRINCE PHILIP |

| Tordesillas, Santiago de Compostela, La Coruña (13th June 1554), Southampton (24th July), Winchester, London and other Tudor residences (mid-August 1554–August 1555), Brussels (September 1555–January 1556). Antonio de Cabezón returned to Ávila (Spain). |

From 1548, Cabezón was in the exclusive service of Prince Philip. This decision was taken at the start of the prince’s journey to Italy, Austria and Germany, where he was to be presented as the successor to the Spanish crown in the Low Countries.8 As a member of the entourage, Cabezón departed from Valladolid on the 2nd of October 1548 (Tab. 2). Travelling via Zaragoza and Barcelona, their fleet of one hundred ships was received in Genoa by Admiral Andrea Doria himself. From Genoa, they travelled on through Milan, Cremona, Mantua, Rovereto and Trent. They crossed the Alps via Bolzano and Brixen, arriving in Innsbruck in early February of 1549. Here the entourage was received by Ferdinand I, the regent of Austria and Prince Philip’s uncle. They continued on through Munich, Augsburg, Ulm, Heidelberg, Luxembourg and Namur, arriving in Brussels on the 1st of March 1549, six months after their departure from Spain. Prince Philip finally joined his father, the Emperor Charles, as well as the Emperor’s two sisters, Queen Mary of Hungary and Queen Eleanor of France. After an initial four-month stay in Brussels, the retinue (Cabezón ever present in the roster) visited the most important cities in Flanders and Holland, which were ready to acknowledge Philip as the apparent heir to the throne. This trip, along the cities listed in Tab. 2, took more than three months. They then returned to Brussels and remained for another seven months, finally departing at the beginning of June 1550. Thus, Cabezón spent a total of fourteen months in the Low Countries in the course of this journey.

On the 7th of June of 1550, Philip and his father, accompanied by their respective entourages, departed for Augsburg via Aachen and Cologne. There they were hosted by the Fugger family and attended the Diet of the Holy Roman Empire. Its main agenda at the time was to contain the spread of Protestantism in Europe. Their stay in Augsburg lasted more than ten months: from the 8th of July 1550 to the 25th of May 1551.9 They finally returned to Spain via Genoa in July 1551. In total, Cabezón’s journey in the service of the prince lasted two years and eight months.

Just three years later, Cabezón again accompanied Philip on his journey to England to marry Queen Mary Tudor. They departed from Spain on the 13th of June 1554, this time with a fleet of 125 ships, arriving in Southampton 41 days later. The princely court settled in Winchester, where the wedding was celebrated in the cathedral. Their arrival in London was delayed until mid-August, where they remained for one year until August 1555, when Philip departed to Brussels for a third visit. Cabezón spent another four and a half months there before he was granted permission to return to Spain. His brother Juan de Cabezón, also a member of the Spanish Royal Chapel since 1546, continued in the Prince’s service.

Thus, Cabezón spent a total of four years and five months of his life away from Spain, with long stays in Brussels (more than fifteen months), Augsburg (more than ten months) and London (one year) and punctuated by visits to many important cities in Italy, Austria, Germany, the Low Countries, England.

It is worth noting, that in addition to other ceremonies, the sung Catholic mass was celebrated daily by the Spanish Royal Chapel in each and every one of the cities they visited. No doubt local musicians participated in many of these ceremonies, religious or otherwise. The frequency and variety of these occasions provided a rich meeting place for Cabezón and a diverse array of musicians, an environment in which he would have encountered many different repertoires and styles of playing. Given his official role as a court organist, he would surely have been able to listen to and perhaps even play many of the organs of the churches in which the Royal Chapel heard and celebrated mass.10

Philip remained abroad until 1559. Back in Spain, Antonio de Cabezón spent the next two years in the service of Philip’s son Prince Carlos in Valladolid, after one year’s leave of absence in his hometown in Ávila to marry Luisa Nuñez. When Philip returned to Spain to rule, Cabezón returned to his service. At this time, the members of the now defunct Emperor’s Flemish Chapel were incorporated into the Spanish Chapel in Madrid, thus strengthening and consolidating the pre-existing musical exchange between these two professional institutions.11

As far as the context of Antonio de Cabezón’s professional life is concerned, the most thorough analysis can be found in the work of the musicologist Macario Santiago Kastner. His research seeks to establish concrete connections between Cabezón and the numerous musicians whom he would have been able to meet, both in Spain and abroad. He notes, for example, Cabezón’s possible influence on Peter Paix, the organist of the Fugger family in Augsburg. This hypothesis is based on the appearance of the first description of the use of both thumbs in the context of German keyboard music, in the writings of Jacob Paix, Peter’s son.12 This practice had been an integral facet of keyboard technique in Spain since the middle of the 16th century, if not earlier. Kastner also notes the presence of a copy of Antonio de Cabezón’s Obras de música in the library of Wolfenbüttel, signed by Gregor Aichinger, an organist and composer active in Augsburg. For Kastner, these facts point to a probable diffusion of Cabezón’s music in the region.13 Moreover, Kastner points out that Cabezón’s visit to London coincides with Thomas Tallis’s duties in the English capital, when he was employed by the Chapel Royal under Mary Tudor. He also speculates on the possibility of a meeting between Cabezón and Tallis’ student William Byrd (who was at this time about fourteen years old), and thus suggests Cabezón’s variations as a model for the style of the English virginalists.14 Appearing some years after Willi Apel’s publication ‘Neapolitan links between Cabezón and Frescobaldi’, Kastner’s observations are part of a well-established line of research into the probable connections between Cabezón and other national schools of composition.15

We could add some more data to those connections. The presence of Obras de música in France, for example, can be traced back to a reference by Pierre Trichet in his Traité des instruments (c. 1640). In 1586, only eight years after the publication of Obras de música, at least seven copies of the book were sent to colonial Mexico. Likewise, two of the extant exemplars preserved in Brussels and Washington D.C. attest to the presence of Cabezón’s music in Portugal.16 One can also imagine Antonio de Cabezón hearing and likely playing the organ of the cathedral church of Notre-Dame in Saint-Omer. Jehan Titelouze was born there in 1562 and later took up his first post as organist in this very church. Also noteworthy is Cabezón’s visit to the Oude Kerk in Amsterdam, which at this time boasted two organs. Jan Pieterzoon Sweelinck began his illustrious career as city organist associated with this church in 1577. Even more intriguing is the meeting in Brussels between Peter Phillips, Peter Cornet and John Bull in the immediate wake of Cabezón’s 18 month stay in this city.

Unfortunately, it is difficult to draw any solid conclusions about these relationships and possible influences in the absence of both concrete documentary references and of any surviving music by many of the musicians whom Cabezón would have encountered (especially those attached to the courts of Brussels and London and to the city of Augsburg). What is known for certain, however, is that having heard and probably played a great many instruments in the course of such widespread travels across Europe, Cabezón proposed to engage a Flemish organ builder when the construction of new organs became an imperative for the Royal Chapel in Madrid.17 In particular, he put forward the name of Jean Crinon, who had built not only the organ of St-Omer mentioned above (later played by Titelouze), but also several other important instruments which he would have known in Brussels, at least from their regular use at state occasions. Crinon declined the royal invitation to work in Spain, because he was already busy with a number of important commissions in Flanders, and by this time, also surely because of his advanced age. These circumstances paved the way for the appearance of Gilles Brebos in the context of organ building in Spain.18 Brebos was commissioned to carry out the most important organ project in 16th century Europe: four large organs for the Basilica of the Monastery at El Escorial. In addition, he provided a variety of smaller instruments, both for the monastery itself and for other institutions associated with the Spanish Royal Court.19

***

All things considered, Antonio de Cabezón’s most important legacy is his music, which still speaks to us eloquently five centuries after its creation. The printed sources account for a total of at least 282 compositions, of which 157 are brief versets or fabordones. A further 125 pieces can be considered major works. The composition of one vocal piece has been attributed to the period of his stay in England.20 Not included in this account are a number of pieces probably by Cabezón, but without any indication of authorship. These are the anonymous pieces published in the Libro de cifra nueva of 155721 and the pieces marked Ca or A.C. in the Coimbra manuscript (P-Cug MM 242).22 Also excluded are pieces by other composers which have been misattributed to Cabezón.23

As presented in Tab. 3, the preserved repertoire is remarkable for its quantity and in its variety. These qualities led Willi Apel to define Antonio de Cabezón as an exception in the panorama of 16th-century European keyboard music, since his output includes examples that represent the full range of genres and styles used by the musicians of his time.24 In absolute terms, because of the large amount of surviving music, he occupies a position among Renaissance composers of keyboard music which is similar to that of Francesco da Milano in the field of lute music.

| Tab. 3: Pieces by Antonio de Cabezón preserved in printed sources | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1557 | 1578 | Total | |

| Tientos | 15 | 12 | 27 |

| Hymns | 17 | 20 | 37 |

| Versets | – | 124 | 124 |

| Fabordones | 1 | 32 | 33 |

| Intabulations | – | 42 | 42 |

| Diferencias | 3 | 9 | 12 |

| Others | 3 | 4 | 7 |

| Total | 39 | 241 | 282 |

Although all of the tientos by Cabezón printed in 1557 and half of those published in 1578 generally fit the ricercar or the fantasia models,25 six tientos in Obras de música exhibit considerable originality at many levels. Commenting on these six pieces, Willi Apel writes that each of them, ‘is a master-piece, and has individual features and many remarkable and captivating details’.26 Combining imitative sections with others based on fabourdon techniques, they anticipate the toccata style, a genre whose nascent features scarcely appear in any other keyboard repertoire before Cabezón’s death in 1566. Of the six, Apel believes that it is the Tiento de primer tono which ‘represent[s] the climax of Cabezón’s works’.27 In many respects, the style achieved by Cabezón in these pieces not only predates the style developed in the tientos of Aguilera de Heredia, Correa de Arauxo or Rodrigues Coelho in Spain, but also exhibits many of the techniques explored in the fantasias of Sweelinck and Pieter Cornet.28

With regard to the hymn settings, Willi Apel likewise observes that, ‘no organ master crystallised this [cantus firmus] style so purely, filled it so perfectly with content, as Cabezón’.29 Many extraordinary passages in these pieces confirm a unique approach to diminution. For those hymns in which Cabezón places the melody as a cantus firmus in the bass, the resulting texture heralds the style adopted by Titelouze for each of the opening versets of his own Hymnes, published in 1623. Among other conspicuous outliers is a singular Pange lingua composed in protus mode, with the cantus firmus maintained in tritus.

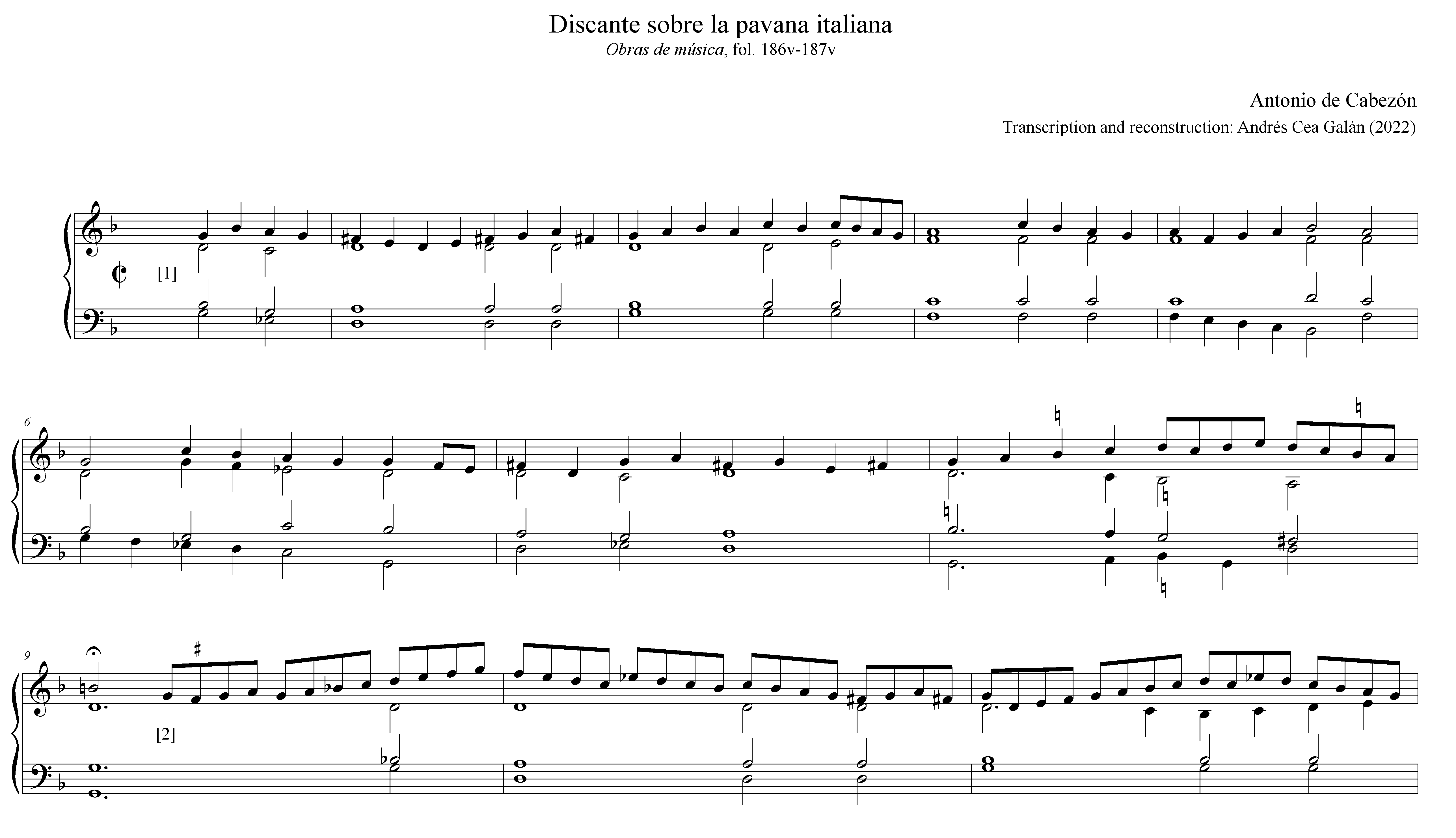

No less remarkable is Cabezón’s collection of diferencias (variations). Among them, the Diferencias sobre el canto llano del caballero is an elaboration of the cantus firmus of the Gombert chanson ‘Dezilde al cavallero’, presented successively in the sopran, tenor, altus and bass. This same technique is found in the work of later composers, including in that of Sweelinck and Titelouze. Cabezón’s other diferencias are developed as variations on a ground, but with incessant reference to the original melodies. Among these, three are clearly constructed adhering to Italian dance forms: Discante sobre la pavana italiana, Diferencias sobre la Gallarda milanesa and Diferencias sobre la pavana italiana. The Diferencias sobre el canto de La Dama le demanda is simply another version of the same Italian pavan, a piece later reproduced by Thoinot Arbeau in the Orchésographie of 1588. From this collection, the Discante sobre la pavana italiana (Appendix 1) emerges as a highly significant piece, for it became a model reused by John Bull, Sweelinck, Scheidt, Thomas Robinson, Alfonso Ferrabosco, Michael Praetorius and many other European composers, who often acknowledged its provenance with such titles as Spanish pavan or Pavana hispanica.30

Three pieces in Obras de música are based on the ground of Las Vacas, a Hispanic variant of the Romanesca. However, it is the Diferencias sobre el villancico de quien te me enojó Isabel that stand out as the most remarkable of Cabezón’s variations (Appendix 2). As has already been expressed in an article,31 this piece comes down to us in a corrupted version. This is probably due to the fact that Cabezón’s son Hernando copied and published his father’s music from incomplete or imperfect drafts. This piece consists of three main sections: the first presents four complete variations on the passamezzo moderno; the second comprises two variations and is constructed as a pavan on the same ground, albeit harmonically enriched, with the main melody in the bass. This latter technique echoes the style found some decades later in the pavans composed by William Byrd. The final section exhibits many textural changes, which according to subsequently codified performance practices can suggest interesting changes of character and tempo in the overall context of a style which also anticipates some elements of the nascent Italian toccata.

Apart from these phenomena, it is perhaps the collection of intabulations (based on 3, 4, 5 and 6-part chansons, madrigals, motets and sections of the mass), which represents Cabezón’s most valuable contribution to the keyboard repertoire. The importance of the intabulations in terms of volume is immediately evident when comparing the number of pages devoted to each of the genres represented in Obras de música, as shown in Tab. 4:

| Tab. 4: Obras de música. Repertoire in proportion | |

|---|---|

| Duos | 2% |

| Tercios | 2% |

| Versets and fabordones | 11% |

| Kyries | 5% |

| Hymns | 6% |

| Tientos | 9% |

| Intabulations | 57% |

| Diferencias or Variations | 8% |

There are several elements of interest in these intabulations that merit further scrutiny, such as the homogeneous distribution of the diminutions between the different voices as well as the introduction of imitative techniques in the ornamental material. Moreover, Cabezón seems to be the first to write intabulations in six voices with diminutions explicitly for keyboard instruments. Four motets and two madrigals of this kind are included in the publication. Particularly in these pieces, the overall impression is one of the original polyphony reduced to simple chords and consonances while the diminutions flow around. The scales and passages pass from one voice to another in a style that frequently approaches that found in the intonazioni and toccate of the Gabrieli family as well as in those of Claudio Merulo. Nevertheless, there are important stylistic differences between Antonio’s intabulations and those of his son Hernando. Four of Hernando’s intabulations have survived, included in Obras de música, whose title page conspicuously bears his father’s name. As Marie-Louise Göllner asserts in a 1990 article, Hernando makes use of new and advanced imitative techniques and treats each verse of the original work differently in relation to the meaning of its text. In her view, the appearance of similar elements in the music of succeeding generations connects his compositions with the toccata and madrigale passeggiato style developed by Neapolitan composers (among them Ascanio Mayone and Giovanni Maria Trabaci) some three or four decades later.32

***

Interest in Cabezón’s music is heightened by the fact that there is an enormous quantity of information about his playing style at the keyboard, as well as about his compositional process. The principal source for this information is Arte de tañer fantasía, published by Tomás de Santa María in 1565.33 This book includes the first and most complete description of all the fundamental aspects of keyboard music interpretation: the position of the hands and fingers, fingering, articulation, ornamentation and diminution. Santa María readily informs us that his work was supervised by both Antonio and Juan de Cabezón. Just as it was addressed to the musicians and theorists of their time, this affiliation continues to affirm the work’s faithful transmission of the interpretative and compositional tradition of the Cabezón brothers.34

It bears noting that Santa María’s treatise presents an evidently advanced approach to fingering in the context of mid-16th century Europe, with extensive use of the thumb in both hands and the use of groups of two, three, four and even five fingers up and down in succession (arreo).35 With regards to ornamentation, Santa María offers descriptions of both small ornaments and trills as well as diminutions. He also differentiates between the ‘old’ and ‘new’ ornaments, encouraging players to apply the latter rather than the former, and therefore implying a clear idea of evolution, progress and adaptation to the prevailing tastes of the day. These ‘new’ ornaments start on the upper note and before the beat. Curiously, the quantity and quality of information about ornamentation transmitted by Santa María and other Spanish theorists contrasts with an almost total absence of signs in the music itself indicating where these ornaments are to be played. The exact opposite situation occurs in the English repertoire of the same period, wherein an abundance of signs in the musical sources contrasts with a lack of information about the meaning of these signs.36

Perhaps the most interesting part of Santa María’s treatise refers to the practice of ‘tañer con buen ayre’ (‘playing with good taste’). This signifies primarily an articulation technique, but also a manner of inégal interpretation. In tandem, these two elements are associated with good taste or grace in playing.37 Similar forms of inégalité likewise existed in France and Italy at this time. As Anne Smith writes broadly concerning Renaissance music, ‘this is one of the areas of 16th century performance practice where much may still be discovered’.38

Furthermore, Santa María’s book is a manual for the study of polyphonic improvisation, describing Renaissance compositional techniques in all their rigour as well as how to apply them extempore.39 From this wealth of detailed contemporary information, Antonio de Cabezón emerges as the sole composer of Renaissance instrumental music for whom such a complete textual record exists, both of the prevailing method of composition and of the interpretation of his work. In this respect he can only be compared to Claudio Merulo who actively participated in the writing of Girolamo Diruta’s treatise Il Transilvano.

***

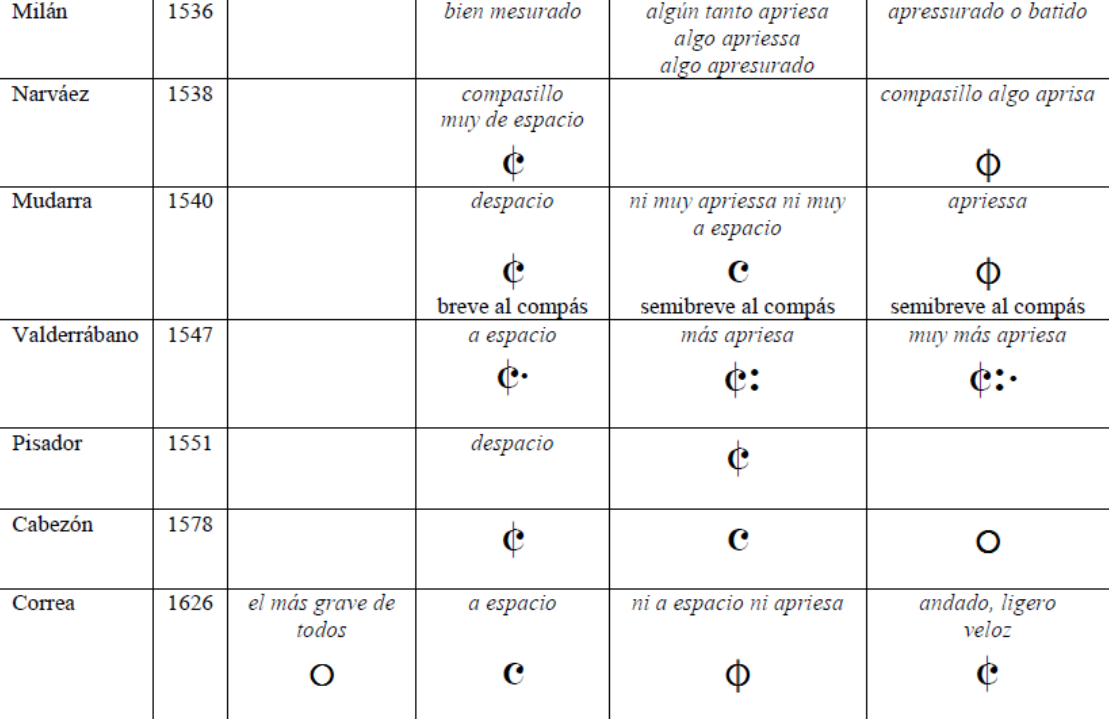

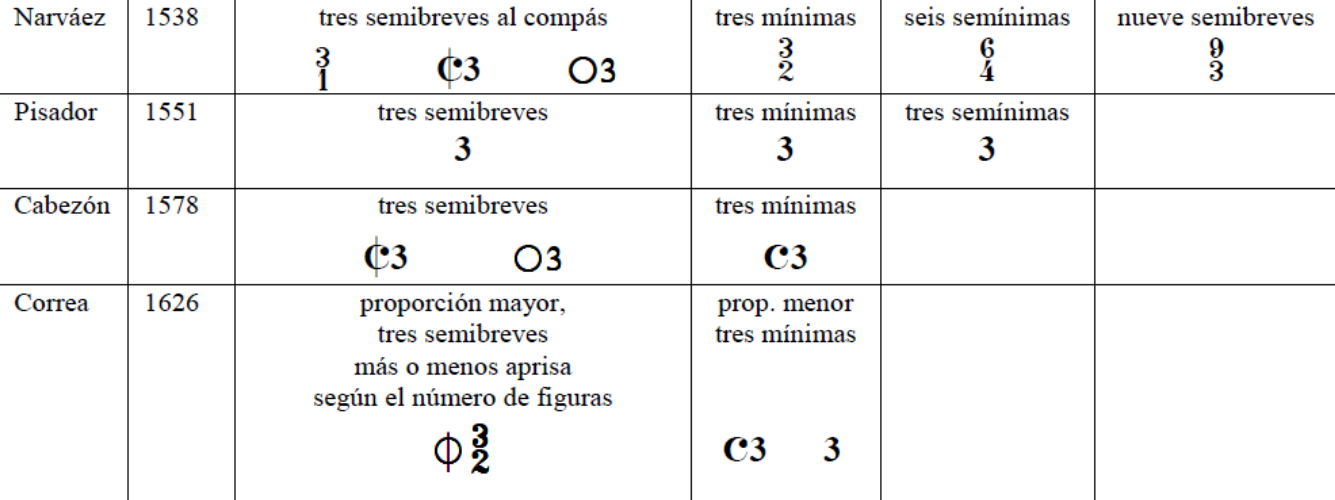

Another prominent feature of Obras de música is the inclusion of a complete system of both binary and ternary tempo indications (Tabs. 5 and 6). These were used to indicate the proper playing speed of a piece or sections thereof, following a practice previously described in multiple vihuela books published by Milán, Narváez, Mudarra, Valderrábano and Pisador. In one way or another, together with Cabezón, they anticipate the use of the terms adagio and allegro invented in Italy for similar purposes around the year 1600. The Spanish system of indicating tempo reaches its peak with the Facultad orgánica of Francisco Correa de Arauxo, published in 1626.40 41

| Tab. 5: Binary tempo signatures in Spanish printed sources (1536–1626) |

|---|

|

| Tab. 6: Ternary tempo signatures in Spanish printed sources (1538–1626) |

|---|

|

These tempo indications are complemented by Luis Milán’s instructions concerning the concept of ‘tañer de gala’42 on the vihuela. He describes a refined manner of playing and implies alternating between slow and fast sections in a single piece.43

Nearly two centuries later, Pablo Nassarre, a student of Pablo Bruna, describes a similar manner of playing in his publication Escuela música (1724),44 in which he compares the performance practices of the Spanish and Italian musicians of his time. According to his description, both groups played ‘especially in instrumental music’ alternating between slow and fast sections within a piece. However, it is the ‘early Spanish masters’ (as Nassarre refers to them) who preferred to handle transitions between sections by applying accelerando and ritardando, while it was the Italians who performed tempo changes abruptly.45 Nassarre thus attributes to these early Spanish musicians a practice which at present, interpreters tend to associate solely with the Italian style cultivated by members of the Frescobaldi circle. It is also possible that Nassarre had in mind the Italian sonata or cantata style of the 17th century. A more difficult task, however, is to locate the music of Spanish origin to which he refers. Although it can be inferred that he was addressing his remarks to keyboardists and organists, it seems evident that Nassarre’s general approach is equally applicable to the vihuela/guitar and harp repertoire, as well as to some vocal music. Though a connection can be made with Milan´s instructions of 1536, it is otherwise difficult to establish with any degree of certainty the provenance of this Spanish approach to the performance of instrumental music as described by Nassarre. With regard to the practice of tempo changes in Spanish music, it is worth noting that the term allarga la batutta first appeared around 1600 in the music of composers such as Giovanni Maria Trabaci, all of whom were associated with the Spanish court in Naples.

***

Another important aspect in the European context of Cabezón’s music is the question of temperament and the different approaches to the tuning of musical instruments described in Spanish treatises. Apart from a controversial precedent expressed by Gonzalo Martínez Bizcargui (1511), the aforementioned Santa María was the first in Spain to characterise the diatonic, or singable (cantable) semitone as ‘major’. He thus positions himself as an advocate of a novel approach to temperament, as first defended in Italy by Zarlino in 1558 and later again in Spain by Salinas in 1577 (Tab. 7).

| Tab. 7: Spanish treatises classified according to their consideration of the diatonic semitone as minor (Pythagorean approach) or major (Meantone approach) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diatonic semitone as minor (Pythagorean) | Diatonic semitone as major (Meantone) | |||

| Domingo Marcós Durán | Lux bella | 1492 | ||

| Guillermo de Podio | Ars musicorum | 1495 | ||

| Alfonso Españón | Introducción de canto llano | 1498 | ||

| Diego del Puerto | Portus musice | 1504 | ||

| Francisco Tovar | Libro de música práctica | 1510 | ||

| 1511 | Gonzalo Martínez Bizcargui | Arte de canto llano | ||

| Juan Espinosa | Tractado de principios | 1520 | ||

| Matheo de Aranda | Tractado de canto mensurable | 1535 | ||

| Gaspar de Aguilar | Arte de principios | 1537 | ||

| Fray Juan Bermudo | Arte tripharia | 1550 | ||

| Fray Juan Bermudo | Declaración de instrumentos | 1555 | ||

| Juan Pérez de Moya | Discursos de Aritmética práctica | 1562 | ||

| Luis de Villafranca | Breve instrucción | 1565 | ||

| 1565 | Fray Tomás de Santa María | Arte de tañer fantasía | ||

| 1571 | Juan Pérez de Moya | Tratado de mathemáticas | ||

| 1577 | Francisco Salinas | De Musica | ||

| 1592 | Francisco de Montanos | Arte de música | ||

| Andrés de Monserrate | Arte breve y compendioso … | 1614 | ||

| 1626 | Antonio Fernández | Arte de música | ||

| 1649 | Fray Tomás Gómez | Arte de canto llano, órgano y cifra | ||

| 1672 | Andrés Lorente | El porqué de la música | ||

| 1700 | Fray Pablo Nassarre | Fragmentos músicos | ||

| 1707 | Antonio de la Cruz Brocarte | Médula de música teórica | ||

| 1742 | José de la Fuente | Reglas de canto llano | ||

| 1748 | Antonio Ventura Roel del Río | Institución harmónica | ||

| 1760 | Diego de Roxas y Montes | Promptuatio armónico | ||

| 1761 | Gerónimo Romero de Ávila | Arte de canto llano | ||

| 1765 | Pedro de Villasagra | Arte y compedio | ||

| 1767 | Manuel de Paz | Médula de canto llano | ||

| 1776 | Francisco Marcos y Navas | Arte o compendio general | ||

| 1778 | Francisco de Santa María | Dialectos músicos | ||

More fundamentally, the first rejection of the classical Pythagorean division of the octave is found in the treatise Musica práctica (Bologna: Baltasar de Hyrberia, 1482) written by Bartolomé Ramos de Pareja. Later, Juan Bermudo presents an exemplary approach to equal temperament in his Declaración de instrumentos musicales.46 Using the term preparación to describe the process, his method is based on the division of the syntonic comma into three parts. Bermudo also proposes a modified version of this temperament suitable for the organ, the result of which approximates 1/8 comma meantone. As shown, Bermudo’s preparación of the syntonic comma anticipates the concept of participatio utilized by Zarlino in his mathematical and geometric definition of the various meantone temperaments.47

***

Antonio de Cabezón’s responsibilities as chamber musician at the Spanish court offer a final point of interest. Although he was then, as now, renowned as an instrumentalist, his duties also included singing. The eyewitness account of Pierre Maillard describes Cabezón singing while accompanying himself at the keyboard. A number of the hymn settings and motet intabulations included in Luis Venegas de Henestrosa’s Libro de cifra nueva are presented with their original texts printed in such a way that they align with the notated music (Tab. 8). This seems to suggest the practice described above, that of singing at the organ (cantar al órgano). In any case, the presence of these texts alongside the music opens up new perspectives for the interpretation of this repertoire.48

| Tab. 8. Libro de cifra nueva, 1557: Keyboard pieces in tablature printed with text | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Psalms | Motets | Chanzonetas / Villancicos | Hymns and others |

|

Cum invocarem Fabordón, in 4 parts |

Aspice Domine Palero, in 5 parts Text in the bass |

Iesu Christo hombre y Dios Polyphony in 4 parts |

Sacris solemniis Ioseph vir Polyphony in 4 parts c.f. in the sopran |

|

Nunc dimittis Fabordón, in 4 parts |

Si bona suscepimus Palero, in 5 parts Text in the bass |

Míralo como llora Polyphony in 6 parts Text applied to second soprano |

Salve regina, Antonio de Cabezón, in 4 parts Text in the bass |

|

Non accedet In 5 parts Text in the bass |

De la virgen que parió In 4 parts Text in the bass |

O gloriosa domina Polyphony in 3 parts c.f. in the tenor |

|

|

In pace In 5 parts Text in the bass |

Mundo qué me puedes dar In 5 parts Text in the bass |

Te Matrem Dei laudamus Fabordón, in 4 parts |

|

|

Al rebuelo de una garça In 4 parts Text in the bass |

|||

***

To conclude, even with the wealth of information available to help us interpret the music of Antonio de Cabezón, something will always be missing. Its real essence is not captured on paper or in the minutiae of Santa María, Milán and others; the scores and treatises alone cannot not describe all that it takes to achieve a convincing rendition. This repertoire lived in the mind, in the imagination of the blind Cabezón. His music became a true sonic reality to his audience only through his fingers and his voice. In this sense, one must always maintain a critical attitude when confronting Cabezón’s musical texts, especially bearing in mind the difficult circumstances surrounding their transmission, having passed first over the desk of copyist Pedro Blanco before their final delivery into the hands of Hernando de Cabezón. One must also consider the further editorial challenge which this music presented to Hernando himself, and also to Venegas de Henestrosa.49 Above all, it is essential to accept the impossibility of reaching the true centre, which is a complete understanding of the original meaning and importance of Antonio de Cabezón’s music, both in his context and in ours. Such efforts can never be in vain, however, as this music has been heralded as that of a new Orpheus, praised for ‘sweetness’, but also admired because of its ‘strangeness’.50

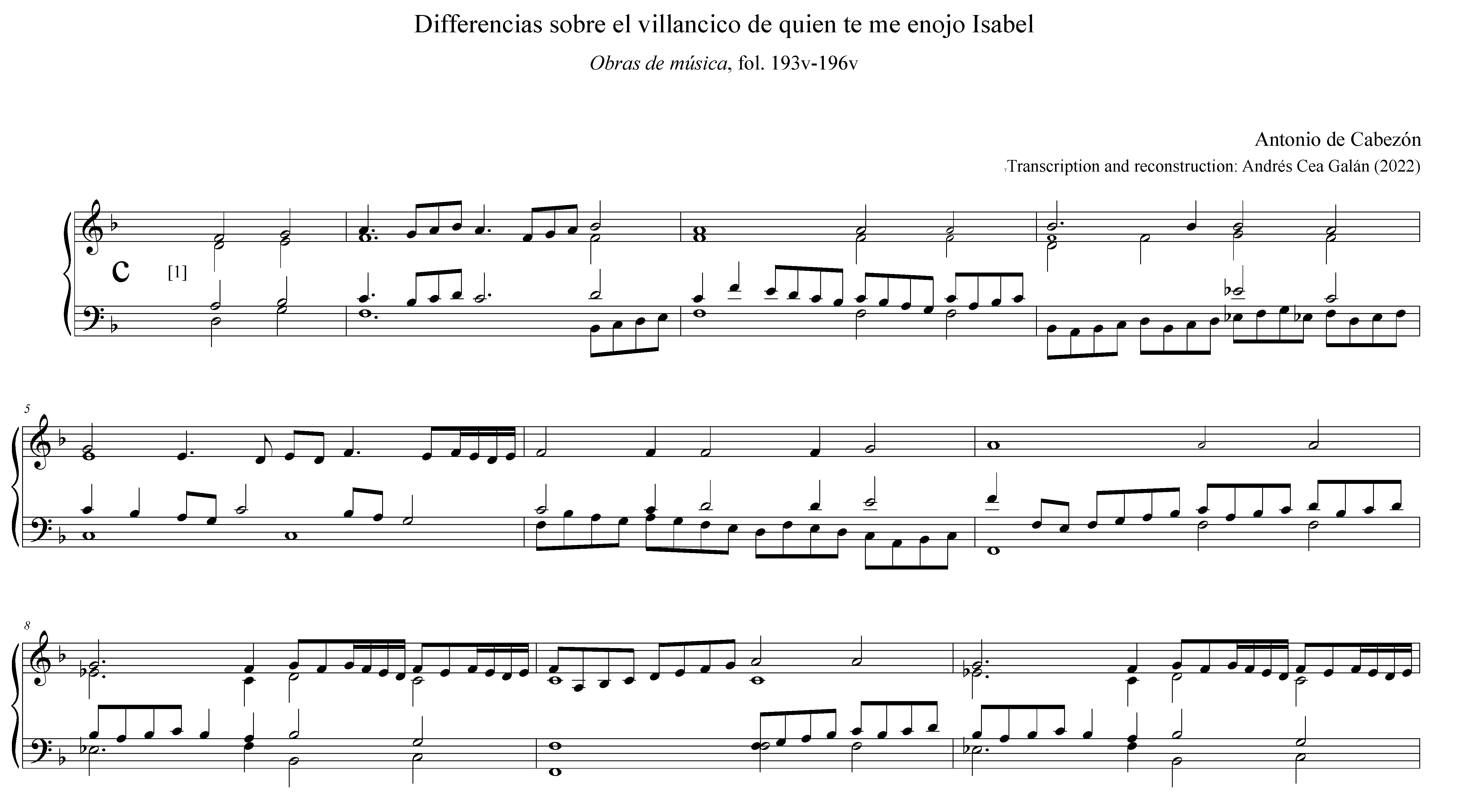

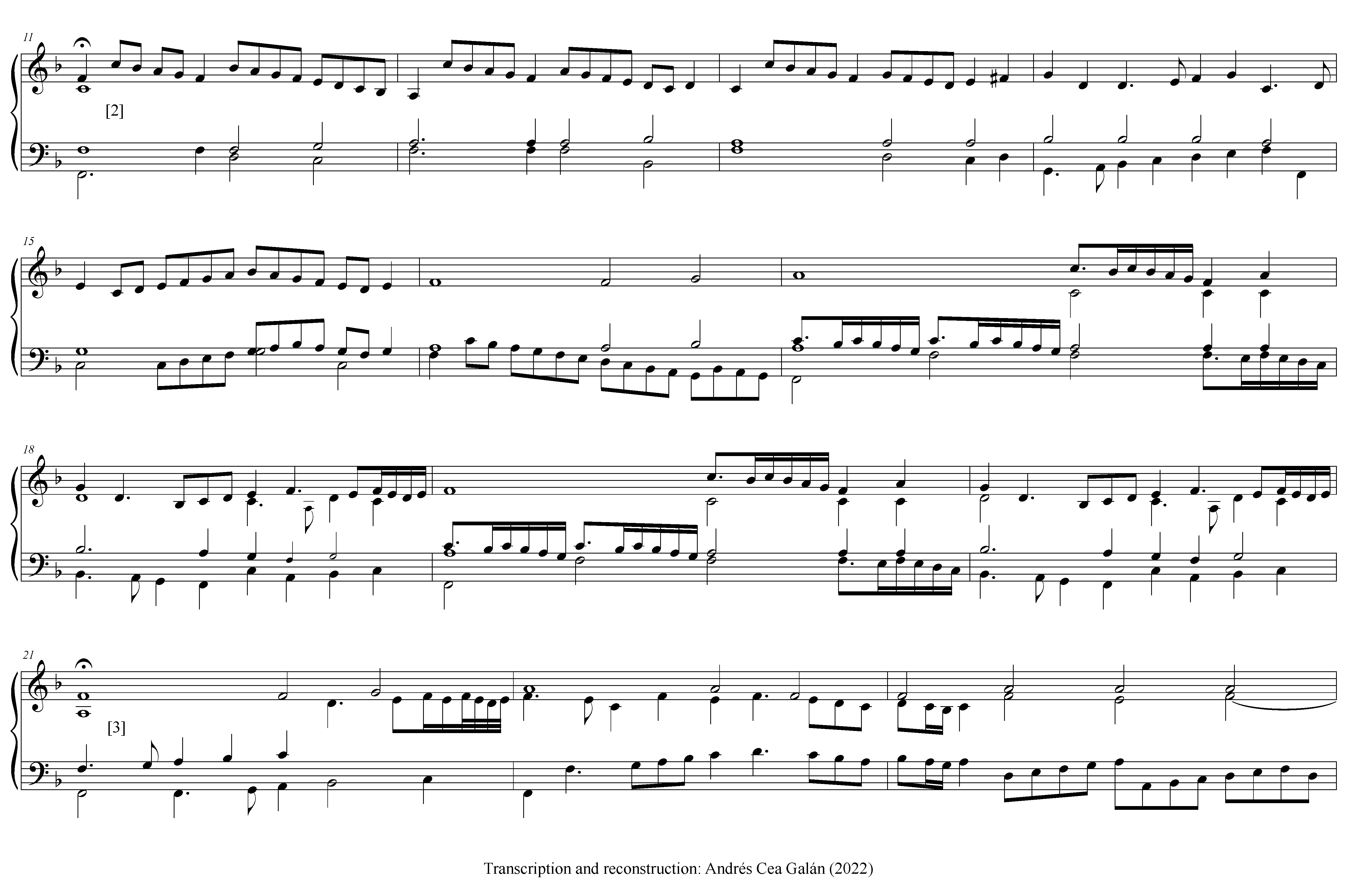

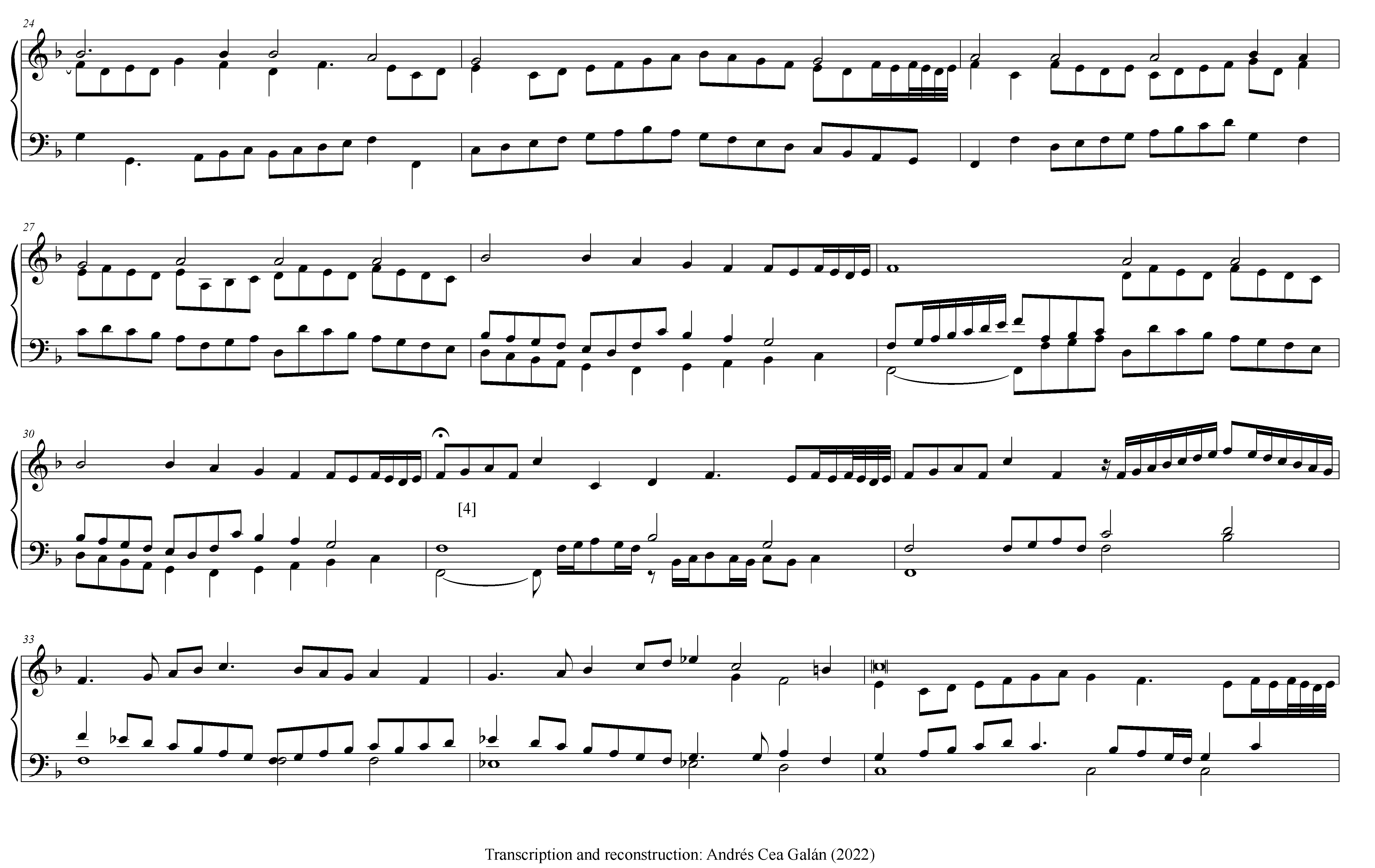

Appendix 1

Antonio de Cabezón, ‘Discante sobre la pavana italiana’, in: Obras de música (Madrid, 1578), fol. 186v–187v.

Transcription and reconstruction: Andrés Cea Galán

This edition is based on the analysis presented in a prior journal article ‘Nuevos pasajes corruptos en las Obras de música de Antonio de Cabezón’ (2010).51 In order to paint a clearer picture of the metric structure of the piece (exemplified by its characteristic up-beat opening) in this edition, each bar is equivalent to two bars of the original. Original note values have been retained. Bars 40 and 48–49, missing from the original source, have been reconstructed and are differentiated in the score by a slightly reduced font size. Additional chromatic alterations are signaled above and beneath certain notes. Previously used to indicate the end of each variation, certain fermatas have been restored to their proper places. Each variation has been assigned a number in brackets. Each performer may view these modifications as suggestions, which in no way should hinder any personal interpretative decisions concerning both the structure and details of this composition with reference to the original source material.

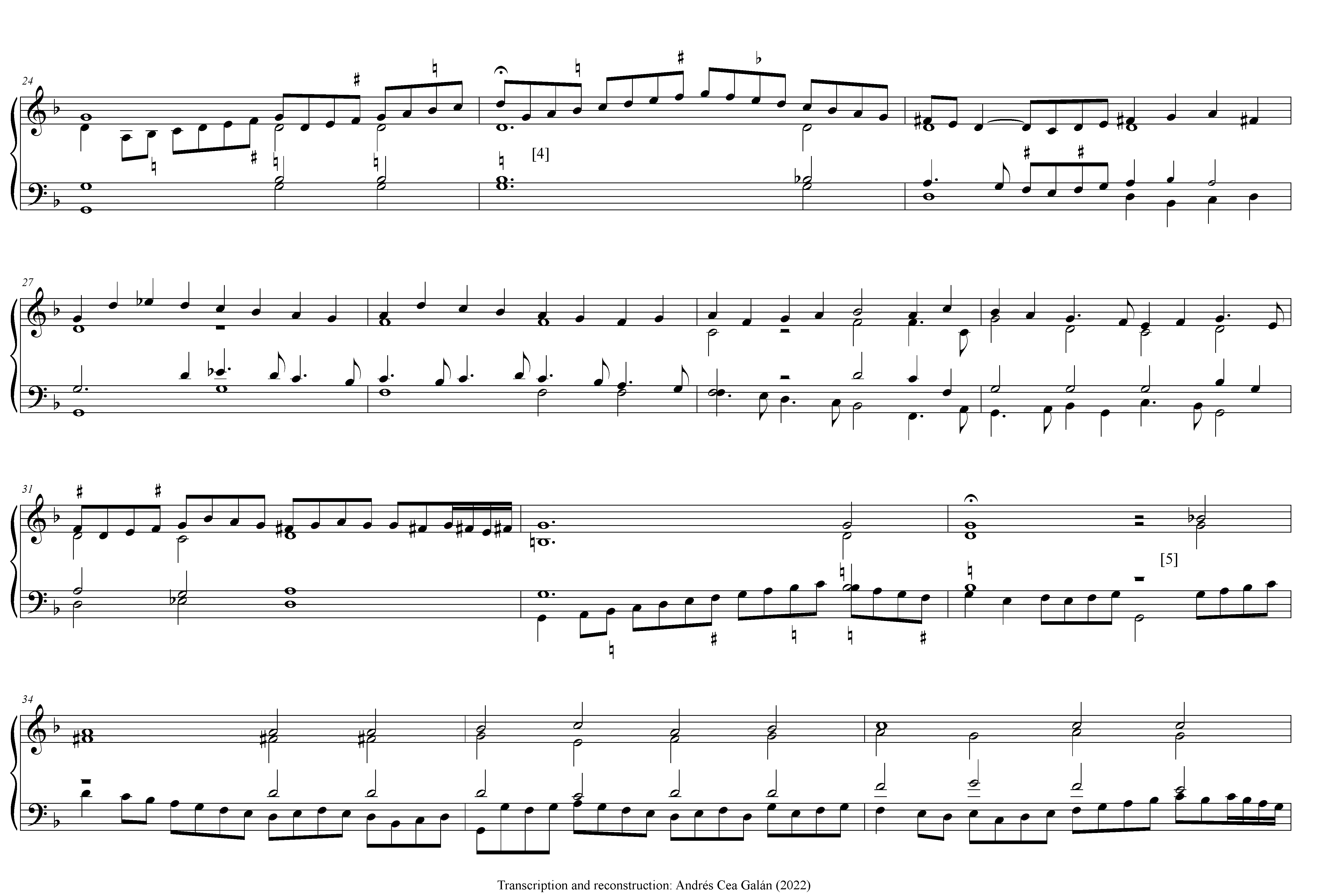

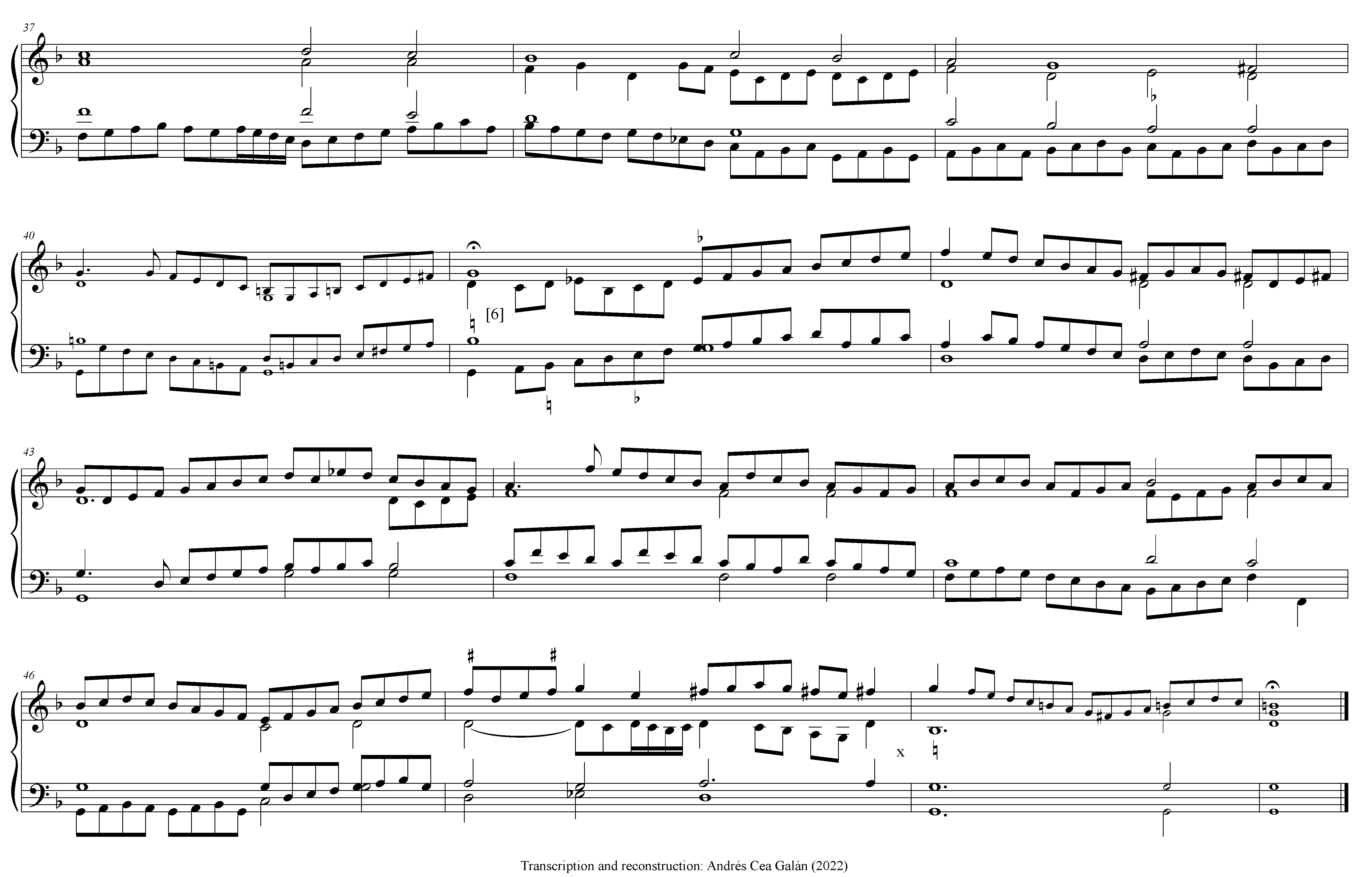

Appendix 2

Antonio de Cabezón, ‘Diferencias sobre el villancico de quién te me enojó, Isabel’, in: Obras de música (Madrid, 1578), fol. 193v–196v.

Transcription and reconstruction: Andrés Cea Galán

This edition is also based on a previous analysis made in another article, ‘¿Quién te me enojó, Isabel? y otras preguntas sin respuesta en las obras de música de Antonio de Cabezón’ (2007),52 wherein a preliminary version was presented. This piece comes down to us from the original source in a fairly corrupted version. Specifically in b. 17, and beginning from b. 19 on, the note values have been doubled in the original printed version, thereby obscuring the structure of the piece as a whole. Furthermore, the reprise included in each variation has usually been misplaced, as is the case with the fermatas indicating the end of each variation. In the original, only the first variation up to the middle of the second is presented in a correct reading. From an editorial point of view, the last variation is especially problematic in its presentation of unnecessary repeated bars among other inconsistences. Thus, in its reconstruction, the present version presumes the original structure and form of each variation.

Likewise, each bar is equivalent to two bars of the original so as to paint a clearer picture of the piece’s metrical structure, especially as it opens on an up-beat. Occasional notes missing from the original have been restored and are differentiated in the score by a slightly reduced font size. Additional chromatic alterations are signalled above and beneath certain notes. The fermatas have been restored to their proper places. Each variation has been assigned a number in brackets. Each performer may view these modifications as suggestions, which in no way should hinder any personal interpretative decisions concerning both the structure and details of this composition with reference to the original source material.

Endnotes

Bibliography

Willi Apel, ‘Neapolitan links between Cabezón and Frescobaldi’, in: MQ 24 (1938), 419–37

Willi Apel, The History of Keyboard Music to 1700 (Bloomington, 1972)

Juan Bermudo, Declaración de instrumentos musicales (Osuna: Juan de León, 1555), <http://bdh.bne.es/bnesearch/detalle/bdh0000046174>

Cristina Bordas, ‘Nuevos datos sobre los organeros Brebos’, in: Livro de homenagem a Macario Santiago Kastner, ed. Maria Fernanda Cidrais Rodrigues, Manuel Morais and Rui Vieira Nery (Lisbon, 1992), 51–67

Hernando de Cabezón, Obras de Música (Madrid: Francisco Sanchez, 1578) (RISM 157824), <http://purl.org/rism/BI/1578/24>

Juan Cristóbal Calvete de la Estrella, El felicíssimo viaje del muy alto y muy poderoso Príncipe don Phelippe (Amberes: Martín Nucio, 1552), modern edition by Sociedad Estatal para la Conmemoración de los Centenarios de Carlos V y Felipe II (Madrid, 2001), <https://bibliotecadigital.jcyl.es/es/consulta/registro.do?id=4546>

Andrés Cea Galán, ‘Órganos en la España de Felipe II: elementos de procedencia foránea en la organería autóctona’, in: Políticas y prácticas musicales en el mundo de Felipe II, ed. John Griffiths and Javier Suárez-Pajares (Madrid, 2004), 325–92

Andrés Cea Galán, ‘Órganos en España entre los siglos XVI y XVII’, in: ISO Journal 23 (July 2006), 6–32

Andrés Cea Galán, ‘Ayre de España: zu Tempo und Stil in der Escuela Música von Fray Pablo Nassarre’, in: In Organo Pleno: Festschrift für Jean-Claude Zehnder zum 65. Geburstag, ed. Luigi Collarile and Alexandra Nigito (Bern, 2007), 113–22

Andrés Cea Galán, ‘¿Quién te me enojó, Isabel? y otras preguntas sin respuesta en las obras de música de Antonio de Cabezón’, in: Cinco siglos de música de tecla española, ed. Luisa Morales (Garrucha, 2007), 169–94

Andrés Cea Galán, ‘Nuevos pasajes corruptos en las Obras de música de Antonio de Cabezón’, in: Diferencias 1, 2ª época (2010), 67–98

Andrés Cea Galán, ‘Nuevas rutas para Cabezón en manuscritos de Roma y París’, in: RdM 34, no. 2 (2011), 223–34

Andrés Cea Galán, ‘New Approaches to the Music of Antonio de Cabezón’, in: Early Keyboard Journal 27–29 (2012), 7–25

Andrés Cea Galán, ‘Cantar Victoria al órgano. Documentos, música y praxis’, in: Tomás Luis de Victoria: Estudios/Studies, ed. Javier Suárez-Pajares and Manuel del Sol (Madrid, 2013), 307–57

Andrés Cea Galán, ‘Audire, tangere, mirari: Notas sobre el instrumentarium de los Cabezón’, in: AnM 69 (2014), 225–48

Andrés Cea Galán, ‘La cifra hispana: música, tañedores e instrumentos (siglos XVI-XVIII)’, Doctoral thesis, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, 2014

Francisco Correa de Arauxo, Libro de tientos y discursos de música práctica y theórica de órgano intitulado Facultad orgánica (Alcalá de Henares: Antonio Arnao, 1626)

Gerhard Doderer, ‘Os manuscritos MM 48 e MM 242 da Biblioteca da Universidade de Coimbra e a presenca de organistas ibéricos’, in: RdM 34, no. 2 (2011), 43–62

Giuseppe Fiorentino, ‘Música española del Renacimiento entre tradición oral y transmisión escrita: El esquema de folía en procesos de composición e improvisación’, doctoral thesis, University of Granada, 2009

Marie-Louise Göllner, ‘The intabulations of Hernando de Cabezón’, in: De musica hispana et aliis. Miscelánea en honor al Prof. Dr. José López-Calo en su 65⁰ cumpleaños, ed. Emilio Casares y Carlos Villanueva, 2 vols. (Universidad de Santiago de Compostela, 1990), i, 275–90

Louis Jambou, Evolución del órgano español. Siglos XVI-XVIII, 2 vols., Ethos música 2 (Universidad de Oviedo, 1988)

Macario Santiago Kastner, ‘Parallels and discrepancies between English and Spanish keyboard music of the 16th and 17th century’, in: AnM 7 (1952), 77–115

Macario Santiago Kastner, Antonio und Hernando de Cabezón. Eine Chronik dargestellt am Leben zweier Generationen von Organisten (Tutzing, 1977); span. ed.: Macario Santiago Kastner, Antonio de Cabezón, ed. Antonio Baciero (Burgos 2000)

Jeannine Lambrecht-Douillez, Orgelbouwers te Antwerpen in de 16de eeuw, Mededelingen van het Ruckers-Genootschap 6 (Antwerpen, 1987)

Luis Milán, Libro de musica de vihuela de mano, intitulado El maestro (Valencia: Francisco Díaz Romano, 1536), <http://bdh-rd.bne.es/viewer.vm?id=0000022795>

Musica nova accomodata per cantar et sonar sopra organi […] (Venice: [Andrea Arrivabene], 1540) (RISM 154022)

Musicque de Joye (Lyon: Jacques Moderne, [c. 1550]) (RISM [c. 1550]24)

Pablo Nassarre, Escuela música según la práctica moderna (Zaragoza: Herederos de Diego de Larumbe, 1724), online: <https://bdh-rd.bne.es/viewer.vm?id=0000014534>

José Sierra Pérez, Antonio de Cabezón (1510–1566). Una vista maravillosa de ánimo (Madrid, Sociedad Española de Musicología, 2010)

Guido Persoons, De Orgels en de Organisten van der Onze Lieve Vrouwkerk te Antwerpen van 1500 tot 1650 (Brussels, 1981)

William Porter, ‘A stylistic analysis of the fugas, tientos and diferencias of Antonio de Cabezón and an examination of his influence on the English Keyboard School’, DMA thesis, Boston University, 1994

Luis Robledo Estaire, ‘Sobre la letanía de Antonio de Cabezón’, in: NASS 5, no. 2 (1989), 143–9

Luis Robledo Estaire, ‘La música en la Casa del Rey’, in: Aspectos de la cultura musical en la Corte de Felipe II, ed. Luis Robledo Estaire et al., Patrimonio Musical Español 6 (Madrid, 2000), 99–193

Miguel Ángel Roig-Francolí, ‘Compositional theory and practice in mid-sixteenth century spanish instrumental music: the ‘Arte de tañer fantasía’ by Tomás de Santa María and the music of Antonio de Cabezón’, PhD thesis, Indiana University, 1990

Miguel Ángel Roig-Francolí, ‘En torno a la figura de Cabezón y la obra de Tomás de Santa María: aclaraciones, evaluaciones y relaciones con la música de Cabezón’, in: RdM 15 (1992), 55–85

‘Miguel Ángel Roig-Francolí, ‘Modal paradigms in mid-sixteenth-century Spanish instrumental composition: Theory and practice in Antonio de Cabezón and Tomás de Santa María’, in: JMT 38 (1994), 249–91

Miguel Ángel Roig-Francolí, ‘Playing in consonances: a Spanish Renaissance technique of chordal improvisation’, in: EM 23 (1995), 437–49

Tomas de Santa María, Libro llamado arte de tañer fantasía (Valladolid: Francisco Fernandez de Cordova, 1565), <http://bdh-rd.bne.es/viewer.vm?id=0000158382&page=1>

Samuel Scheidt. Tabulatura nova, ed. by Harald Vogel, Part II (Wiesbaden/Leipzig/Paris, 1999)

Anne Smith, The Performance of 16th-Century Music. Learning from the Theorists (Oxford, 2011)

Luis Venegas de Henestrosa, Libro de cifra nueva (Alcalá de Henares: Juan de Brocar, 1557), <http://bdh-rd.bne.es/viewer.vm?id=0000039213&page=1>

Cristóbal Villalón, Ingeniosa comparación entre lo antiguo y lo presente (Valladolid: Nicolas Tyerri, 1539), ed. Manuel Serrano y Sanz, Libros publicados por la Sociedad de Bibliófilos Españoles 33 (Madrid 1898), <https://bibliotecadigital.jcyl.es/es/consulta/registro.do?id=18741>