John Griffiths

How to cite

How to cite

Abstract

Abstract

The invention and widespread dissemination of music in tablature was one of the great novelties and a key factor in the proliferation of solo instrumental music during the 16th century. An alternative to mensural notation, tablature offered systems of writing music better suited to polyphonic instruments, particularly keyboards and plucked strings such as lute, guitar, and vihuela. Tablatures emerged in a variety of forms that used the letters, numbers and conventional mensural symbols, and many aspects were shared between the notations devised for keyboards and plucked strings. Although we recognise specific idiomatic styles associated with individual instrument types, there is also a significant amount of music that shares common features and that can be performed on diverse instruments. This was recognised by Spanish musicians such as Luis Venegas de Henestrosa whose tablature published in 1557 was advertised as being for ‘tecla, harpa y vihuela’. This paper explores the idea of interchangeability associated with such tablatures, and a range of issues extending from the particularities of the Venegas book and its emulation by Cabezón in 1578, beyond national borders to consider the nature of tablature across notation styles, and instrumental practice in distinct regions of Europe.

About the Author

About the Author

John Griffiths researches Renaissance music and early instrumental music, especially from Spain. His work ranges from history and criticism to organology, music printing, notation and urban music. His recent work includes an encyclopaedia of tablature (in press), a new edition of the music of Luis de Narváez (Le Luth Doré), and essays on tablature and the nature of Renaissance performance. Currently he holds positions at the University of Melbourne and the Centre d’Etudes Superieures de la Renaissance (Tours). He is Editor of the Journal of the Lute Society of America, vice-president of the International Musicological Society and also performs on vihuela, lute and early guitars.

Outline

Outline

Sources are one of the fundamental pillars of any kind of historical performance practice of music. Particularly for those of us who play polyphonic instruments, reading from the same pages that were used by players in the 16th century – for the purposes of the present study – draws us closer to the essence of the music we are playing, or so we believe. It obliges us to see the music as they did, and it requires us to make many of the same decisions about many aspects of performance that were faced by the musicians who created the pieces we play, or who were its original consumers. From my own perspective as a lutenist and vihuelist, it is quite surprising to see the large number of contemporary harpsichordists and organists who interpret this by playing primarily from carefully edited modern editions, written in modern notation. The contemporary lute world is the reverse: nearly all modern lutenists play from tablature, from the original notation, whether in facsimile reprint or in a modern typeset version of the original. This anomaly of notational practice is the first of the two main discussions within this essay; the other concerns that uniquely Spanish practice of the 16th century of having music ‘para tecla, harpa y vihuela’ that could supposedly be played on keyboards, harp and lute from the same notation.

Tablature of one kind or another was the common notational language for keyboards and other polyphonic solo instruments during the 16th century. The exact extent of the surviving repertoire of works in tablature from before 1600 has not been calculated, but I would estimate it to be in the vicinity of 20,000 works, a substantial amount of music and a repertoire that is large enough not to be ignored. In this essay I wish to discuss some of the broader vision and distilled conclusions arising from a substantial research project about tablature in the 16th century. The project was actually based on all Western tablatures prior to c. 1750 that will soon be published as a single volume of encyclopaedic proportion representing tablatures for over forty instruments.1

Tablatures as Tables

As a point of departure, it is necessary to go back to first principles: to define tablature and to locate it within the broad family of music notations. Most definitions of tablature describe its external features rather than offer a real definition. Tablature is most commonly described as ‘music encoded using letters and numbers’. The Oxford English Dictionary definition, in contrast, is more a description than a definition, encompassing ‘Any of various forms of musical notation, esp. one differing from staff notation’, adding that it is specifically ‘a form of notation used for stringed instruments in which lines denote the instrument’s strings and markings indicate fingering and other features […]’ but omitting to acknowledge the existence of tablatures for keyboards and numerous other instruments.2

Limited as it is, the Oxford definition does not mention the use of letters as symbols. It is the idea of ‘playing by numbers’ that has often encouraged negative attitudes to tablature, as if it were a substitute for real notation, dismissed as simplistic, and categorised as a notation system for amateurs. This is no doubt reinforced by the widespread use of tablature for contemporary popular music, and the belief that it is designed for those who are unable to read conventional notation. Of course, none of this is true. One of the beauties of tablature is that it can be used by amateurs but, at the same time, it is a very sophisticated language that was also regularly used by professionals of the highest calibre.

The closest to a meaningful definition of tablature was given in passing by Johannes Wolf just over a century ago, but has not been taken up subsequently – by him or anyone else, as far as I know. Sometimes the desire for a complex definition interferes with our clarity of vision and blinds us in a way that makes the simplest things elude. After my own particular epiphany concerning the nature of tablature, it was somewhat sobering to realise that Wolf had happened upon the same idea although he chose not to develop it further. On the very first page of the second volume of his Handbuch, the one devoted to tablature, Wolf remarks that:

While the Greeks distinguished between vocal and instrumental notation, in the Middle Ages special types of notation for different instruments, tablatures, were also developed alongside vocal notation. The tabula was the tablet or sheet on which a piece of music was written down. Notations were created for all kinds of keyboard, plucked, string and wind instruments. Letters and numbers along with notes represented its basic elements.3

In the process of trying to define tablature, it is easy to overlook that the real definition of tablature is embedded in the term itself, as Wolf hints. In the other main notation treatise of the last century to deal with tablature, Willi Apel also avoids a direct definition of tablature, instead offering a long explanation that can be reduced to his separation of ‘ensemble music’ from ‘soloist music’, plus a further two elements: tablatures ‘are distinguished by special features such as the use of figures and letters’, in a format which involves ‘the writing of several parts on one staff’ instead of many.4

Having considered these precedents, it is clear to me that the most concise definition of tablature is simply to consider it ‘music put into a table’. Adopted from the Italian ‘intavolatura’ that was first used as the title of Francesco Spinacino’s two books of Intabolatura de lauto published by Petrucci in 1507,5 the term was adapted into most modern European languages, apart from Spain where it was known as ‘cifra’, that is, in cipher. The Italian noun ‘tavola’ has various meanings from a piece of furniture through to a mathematical table, the latter often described as a ‘tabella’ in modern Italian. The resulting verb ‘intavolare’ describes the action of ordering objects rationally as a table, and the related noun ‘intavolatura’ describes objects (music) systematically arranged in a table.

Tables function to condense multidimensional information. To intabulate music – to put it into a table and make a tablature – produces a multidimensional table that arranges the music of individual polyphonic lines in manner that shows how they sound together when played. A musical tablature is therefore a score. The Italian term ‘partitura’ was not invented until the following century when multiple mensural staves were placed above one another on a page in the fashion that has subsequently been known as a score. As is well known from the studies of Jessie Ann Owens and others, polyphonic music was not notated in score during the 16th century.6 Her landmark study of the compositional techniques used by composers of vocal polyphony suggested alternate means that composers may have used during the compositional process to help them in understanding how the individual voices fitted together. Her findings pointed to the possible use of score sketches on paper, but suggested the use of non-permanent means such as incising on wax tablets or writing with chalk on slates among the likely ways that composers worked. Owens flirts with the use of tablature for the notation of scores but does not explore it in depth.

The very nature of tablature allowed music to be presented in a way that was difficult in the standard notational formats of polyphonic music, whether in choirbook format or separate part-books. There are no documented explanations of why mensural copyists did not notate their works in score, especially when considering how it would have simplified composition as well as gaining an understanding of written compositions. It can only be supposed that the reasons were connected to using materials efficiently. Writing separate parts saves parchment or paper particularly through the way that silences are notated. Tablature is even more efficient than mensural parts with a full polyphonic piece often taking less space than a single part. For players performing from the notation, this also greatly reduced the number of page turns.

Research into the use of tablature shows that musicians read both mensural music and tablature. With specific reference to keyboard tablatures, we have examples from Albrecht Dürer through to J. S. Bach who were practised in both formats. Dürer notated fragments of keyboard music in tablature in his sketchbooks and Bach used tablature in seven pieces in his ‘Orgelbüchlein’ to obviate page turns.7 With reference to lutenists, perhaps the most striking example is Palestrina who is known to have refused to send his latest compositions to his patrons until he had written them out in tablature and played them on his lute.8 There are many other documented cases. Examples such as these serve to show that some – perhaps many – musicians in the 16th and 17th centuries were equally at home with mensural notation and tablature. In the case of Palestrina and others like him, tablature appears to have been part of the composer’s toolkit. This implies a form of musical bilingualism that allowed musicians to use different notation forms for different purposes. In the 16th century, it appears that musicians used mensural notation for performing polyphonic vocal music, but often preferred any of the numerous keyboard and lute tablature formats for writing polyphonic scores as well as for other solo instrumental music. This practice persisted in many places throughout the 17th century as well.

Historiography

The factors that have led to unsympathetic academic attitudes to tablature in modern times derive from prejudices that possibly have their roots in the 19th century when ‘playing by numbers’ became increasingly associated with popular music genres and non-symphonic instruments such as the guitar, harmonium or ocarina among others. Restoring the legitimacy of tablature and its place among Western notations requires not only that these prejudices be overcome, but also that a number of related historiographic distortions be addressed and resolved. The outcome of such revisionism will have a positive effect in musicological thinking and also, hopefully, will encourage more contemporary keyboard players to use the historical notations that pertain to their instruments. With few exceptions, modern scholarship continues to deny the centrality of tablature. Tablature repertories are ignored in many writings as if they did not exist, an insignificant marginalised subset of Renaissance music.

The view of tablature as having limited significance is an historiographical issue that is closely tied to the pedagogy of music history. For much of the last century, the most widely used text books used at undergraduate level at universities – at least in the English-speaking world – have portrayed Renaissance instrumental music as little more than an afterthought to the mainstream of vocal polyphony, both liturgical and secular. This is the product of a conception of music that gave priority to sources and music genres over the idea of music as a social experience in Renaissance society.9 The result is the artificial partitioning of Renaissance music into ‘vocal’ and ‘instrumental’ categories, based on sources and notation, mostly without acknowledging that there were bilingual musicians who defied these boundaries and who were both polyphonists and instrumentalists. To separate them into categories would not occur in a social history of Renaissance music based on human activity rather than compositional genres. It is important for players and scholars today to realise that these distortions will not be rectified without effort and that the responsibility is ours to ensure it happens.10

Tablature Types

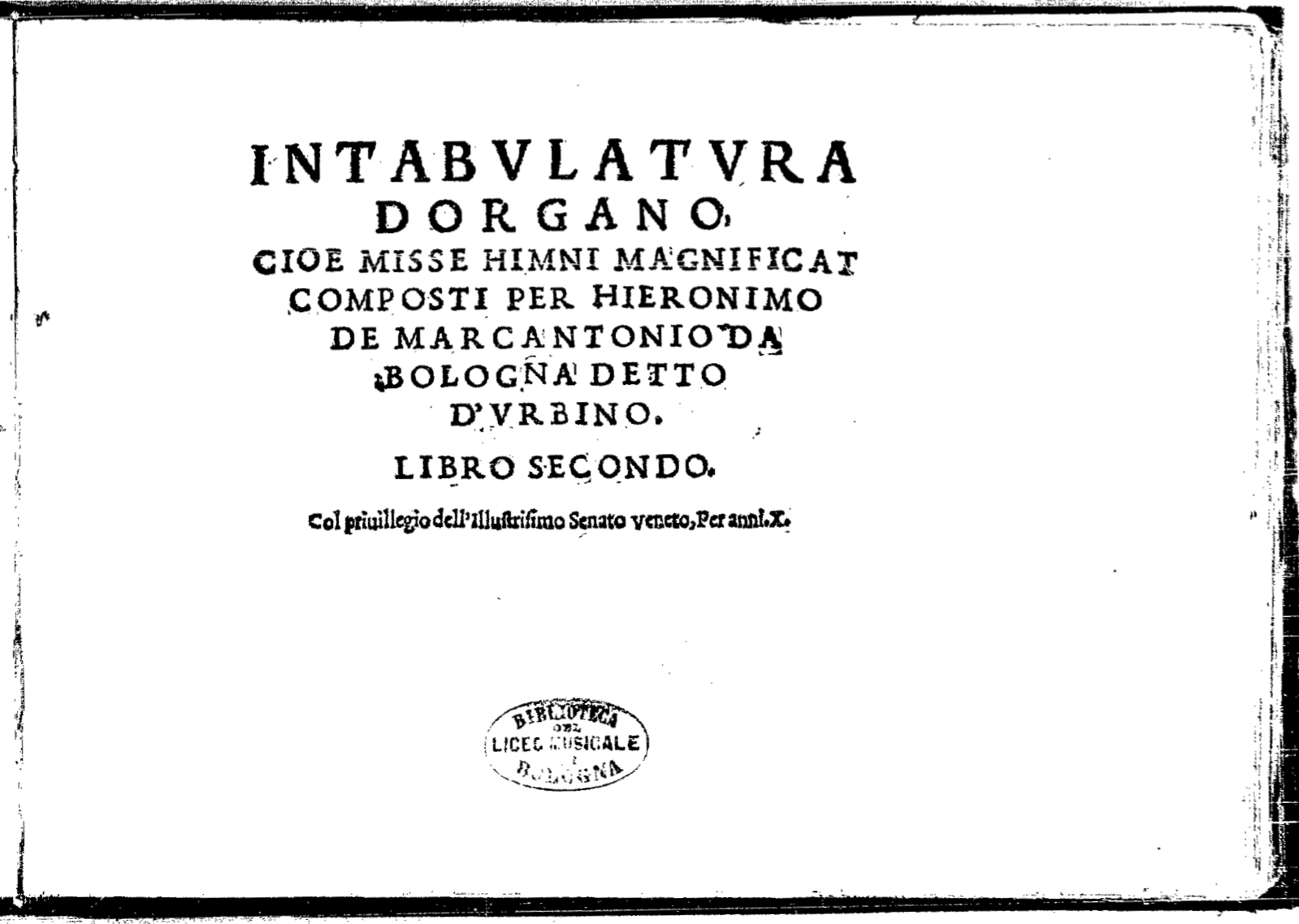

Most tablature is written using letters or numbers to represent pitch. Much 16th-century Italian keyboard music, however, was written in mensural notation on a multi-lined staff, but with all the voices combined onto the one staff, condensed into a table and thus designated by its composers as ‘intavolatura’ or ‘intabolatura’. A perfect example of this is the undated Intabvlatvra d’organo […] libro secondo by Girolamo Cavazzoni published in Venice some time after the libro primo issued in 1543. The title page leaves no doubt as to the composer’s understanding that his book was a tablature (Fig. 1), yet the notation is clearly in mensural notation on a pair of staves, divided according to the hands rather than by voices, although the correlation is very close (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1: Girolamo Cavazzoni, Intabvlatvra d’organo […] libro secondo (Venice [Girolamo Scotto], after 1543), title page.

Fig. 2: Girolamo Cavazzoni, Intabvlatvra d’organo […] libro secondo (Venice [Girolamo Scotto], after 1543), fol. 1v.

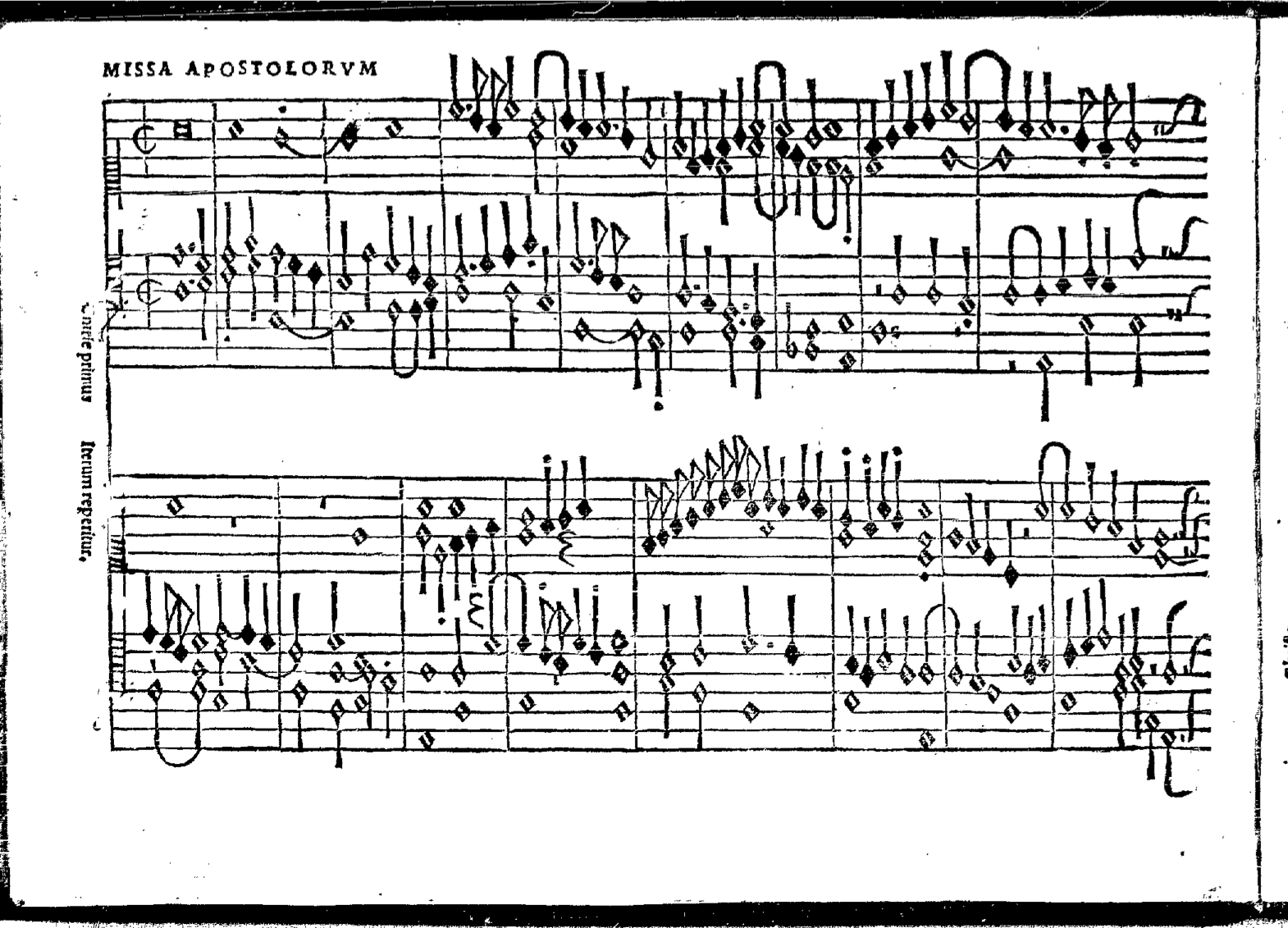

It is clear from the preceding example, then, that Italian keyboard tablatures are not very different to tablatures written with numbers or letters. This is clearly how they were perceived by the musicians who created and used them. Despite the differences in their appearance, especially the symbols for indicating the pitch of notes, they were all considered to be music in table format and, hence, tablatures. In each tablature type, in notation built from numbers, letters or mensural symbols, there are many variants, whether on the basis of the instruments they served, the practices adopted in different geographical locations, or variants designed to improve earlier types or individual differences that are best described as idiosyncratic. There are many family resemblances between certain tablature types whereas others are completely different. In the course of our research, however, we were able to distil these diverse tablature types into two broad families independent of whether they use numbers, letters or mensural symbols to designate pitch. These have been denominated ‘matrix tablatures’ and ‘fingerboard tablatures’. Matrix tablatures are the oldest, and the ones that are particularly relevant to keyboard music (Fig. 3). They are the tablatures that use either numbers, letters or mensural signs to represent pitch, and that have the multiple voices written with each voice as a separate row placed one above another. These tablatures appear first to have developed in the German-speaking world, even though the oldest example dating from the 14th century is preserved in England.11 In contrast, fingerboard tablatures are those in which the lines of the conventional music staff are re-envisaged as the strings of an instrument running along a fingerboard (Fig. 4). The number of lines is defined by the number of strings on the instrument, with numbers or letters to represent the places on the fingerboard where strings are stopped. This tablature seems to come from the Italian peninsula but became common throughout all Europe.

Fig. 3: Josquin des Prez, ‘Benedicta es caelorum regina’, opening, from Jacob Paix, Thesavrvs Motetarvm: Newerleßner zwey vnd zweintzig herrlicher Moteten (Strasbourg: Bernhart Jobin, 1589) (VD16 ZV 26531), fol. 3r. Online: <https://mdz-nbn-resolving.de/details:bsb00031714> (accessed 3 August 2022).

Fig. 4: Vincenzo Capirola, ‘Ricercar otavo’, US-CN Case MS VM C. 25, The Capirola Lute Book (c. 1517), fol. 44v. Online: <http://ricercar-old.cesr.univ-tours.fr/3-programmes/EMN/luth/pages/notice.asp?numnotice=4> (accessed 3 August 2022).

Spanish Keyboard Tablatures

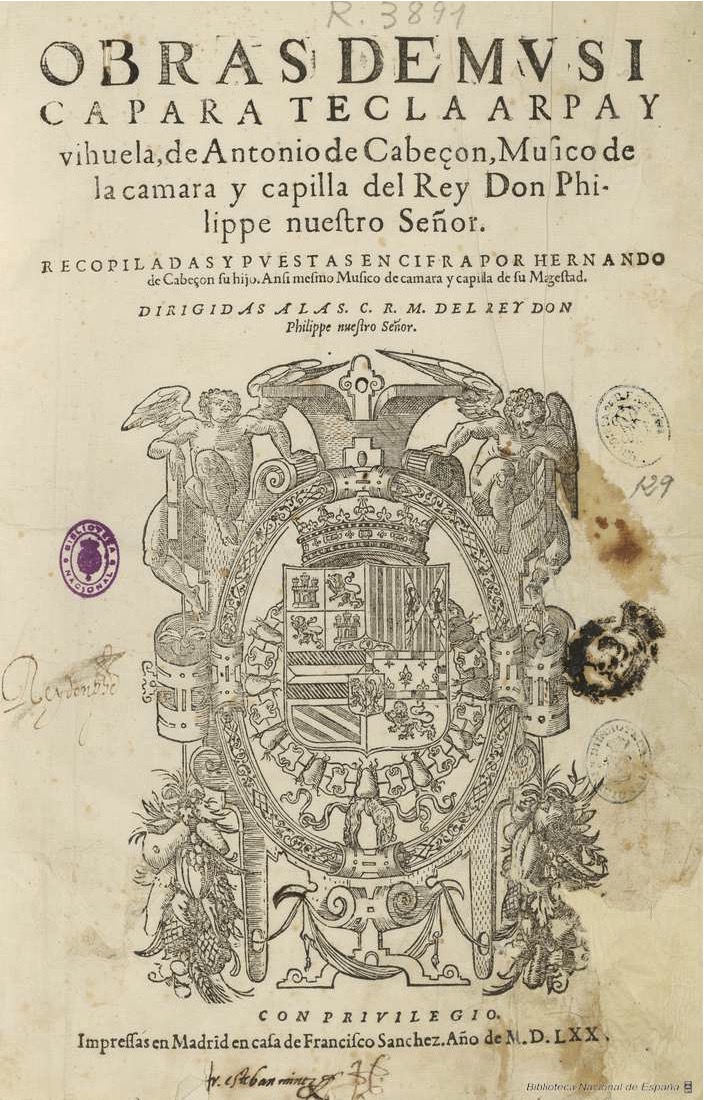

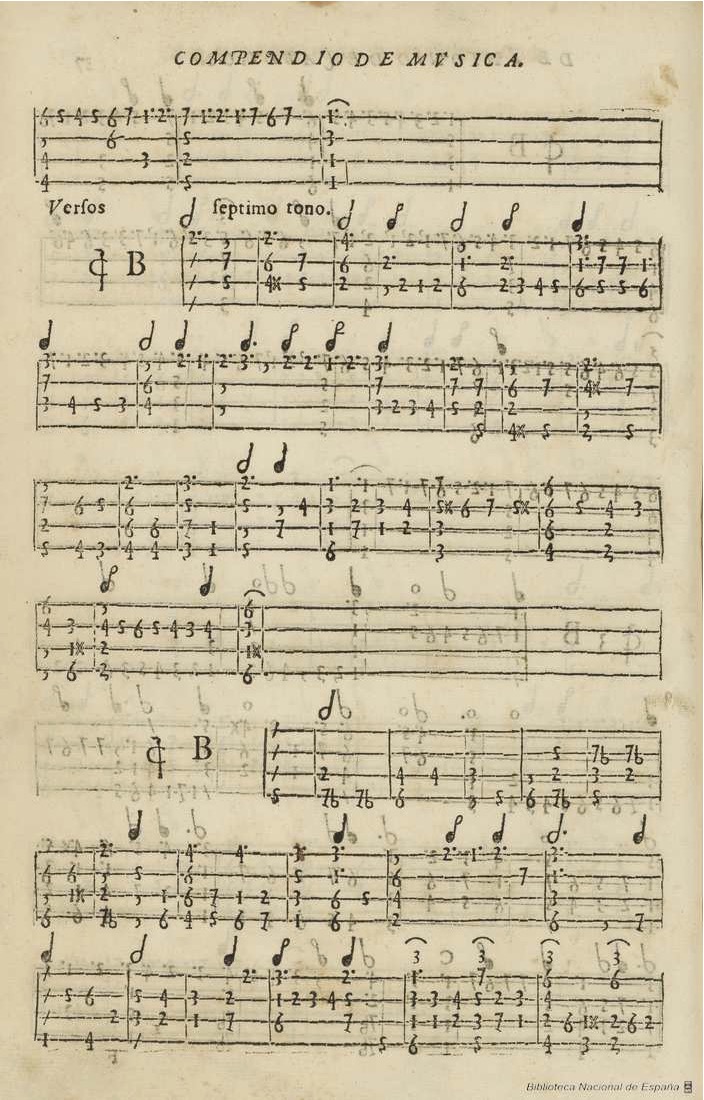

The second part of this essay is directed specifically to keyboard tablatures on the Iberian Peninsula, especially Spain. There is evidence of tablature use in Spain from the early 16th century. The earliest example is a fragment of fingerboard tablature, probably for vihuela, found in the endpapers of a book printed in 1513.12 The earliest keyboard tablature from the Iberian peninsula is the Arte […] pera aprender a tanger (Lisbon: Germao Galharde, 1540) by Gonzalo de Baena, written in an idiosyncratic alphabetic matrix tablature, independent of any other known tablature type. Only fairly recently rediscovered, this book is not so well known, with a first modern edition issued only in 2012.13 The best known type of Spanish tablature was the invention of Luis Venegas de Henestrosa, and used for his Libro de cifra nueva printed in Alcalá de Henares in 1557 by Juan de Brocar (Fig. 5). In the prefatory pages of the book, Venegas explains how he came to invent his tablature and expresses his desire that it should become a universal notation for all solo instruments. With improvements added by Hernando de Cabezón in his publication of the Obras de música of his late father Antonio in 1578 (Fig. 6), Venegas’ tablature became the predominant keyboard tablature used in Spain until the early 18th century. Even though Venegas’ tablature achieved considerable longevity, it is but one of numerous tablature types invented on the Iberian peninsula. These include the organ tablature proposed by Alonso Mudarra in his Tres libros de música (Sevilla: Juan de Léon, 1546), the continuous numeric tablature proposed by Bermudo in his Declaración de instrumentos (Ossuna: Juan de Léon, 1555) and then the dozen or so other Iberian tablatures revealed by Andrés Cea Galán in his doctoral dissertation of 2014.14

Fig. 5: Venegas de Henestrosa, Libro de cifra nueva (Alcalá de Henares: Juan de Brocar, 1557), title page. Online: <http://bdh-rd.bne.es/viewer.vm?id=0000039213&page=1> (accessed 23 June 2022).

Fig. 6: Hernando de Cabezón, Obras de música (Madrid: Francisco Sánchez, 1578) (RISM 158724), title page. Online: <http://purl.org/rism/BI/1578/24> (accessed 24 June 2022).

The present study, however, revolves around Venegas de Henestrosa’s Libro de cifra nueva (1557), and Hernando de Cabezón’s Obras de música (1578), a book that brought into print an anthology compiled many years earlier by Antonio de Cabezón who had died in 1566. The interesting feature of both volumes is that they are subtitled para tecla, harpa y vihuela, an indication that they are ‘for keyboard, harp and vihuela’. The sentiments of this phrase, the insinuation of a common notation and interchangeable repertory for the principal polyphonic instruments of the time, appears to be validated further when it is echoed in the title of Fray Tomás de Santa María’s keyboard treatise of 1565 titled Libro llamado Arte de tañer Fantasía, assi para Tecla, como para Vihuela, y todo instrumento, en que se pudiere tañer a tres, y a quatro vozes, y a mas. (A book called the Art of the Fantasia, equally for Keyboard as for Vihuela, and all instruments upon which one might play in three, four or more voices).15

Uncritical acceptance of this phrase has led to the assumption that the music of these books, if not all Spanish keyboard music is suitable for all three instruments and can be freely exchanged between them. Our musicological forefathers accepted the phrase without question and even if silently, never questioned its veracity. The dominant 20th-century Spanish scholar, Higinio Anglés, in his 1944 edition of Venegas’ Libro wrote, for example, that ‘our organists published music for keyboard, which could also be used for the other instruments in vogue at the time.’16 This view of the interchangeable repertoire of ‘our organists’ has persisted without serious interrogation. My task here is to expose the manner in which this phrase ‘para tecla, harpa y vihuela’ came into existence, how it spread and consequently, to dispel the notion of an interchangeable Spanish repertory for solo instruments. This study demonstrates how Venegas’ use of the term ‘for keyboard, harp and vihuela’ makes sense in the context of his own book, but suggests that Cabezón’s use of the same phrase is likely to have been a hasty last minute addition, probably for commercial reasons. In Santa María’s case, the phrase is not the same, and the precise meaning of his wording needs to be carefully untangled. From the micro-history of these three books it becomes impossible to accept that the use on two occasions of the same phrase reflects a widespread Spanish practice of interchangeability in the way that has often been supposed.17

Venegas de Henestrosa and Hernando de Cabezón

Luis Venegas de Henestrosa (c. 1510–70), a musician in the employ of the Archbishop of Toledo from at least 1535 to 1545, and subsequently a parish priest in the town of Hontoba in Guadalajara, invented a new format of keyboard tablature and used it to compile the anthology that he accordingly named a ‘Book of new ciphers’ adding that it was ‘for keyboard, harp and vihuela’ in a very matter-of-fact fashion to reflect its contents.18 It is genuinely music ‘para tecla, harpa y vihuela’ in contrast to the later book by Hernando de Cabezón which is not. Venegas’ years in Toledo had allowed to move in highly cultured circles and to become familiar with the best music of his time. In contrast, his later life as a parish priest in a small rural community made him aware of the difficulty of access to good music for liturgical use. He begins the preface of his book ‘Al lector’ (To the reader) explaining that he expected to be the subject of the insults of professional musicians for having invented his tablature and thereby creating a ‘shortcut’ that would allow others of very inferior status to learn in a short time what had taken them years to achieve.19 Venegas knew, however, that his book would fill a void. As a church musician, he lamented the lack of competent organists for parish churches. As an organist, he lamented the lack of keyboard music in circulation. He wanted to help fill this void both directly and indirectly: by offering players a useful anthology, but also by inventing a new simple but effective notation, and by giving players tools to expand their own repertoire. He also saw in his tablature the possibility of a universal notation that could be used by all instrumentalists. Even if in modest employ, Venegas was a man with a broad perspective, perhaps an idealist if not a dreamer.

Venegas de Henestrosa’s tablature is remarkably simple. It is a matrix tablature on a staff of a varying number of lines disposed with one line per voice, and the numerals 1-7 used to represent the natural notes of each octave, starting on F (1 = F, 2 = G, 3 = A etc). The music is barred in tactus units and there are no rhythmic symbols: the numbers are spaced so that their duration is to be intuitively intelligible. As can be seen in the following example (Fig. 7) is very easy to read.

Fig. 7: Palero, ‘Primer Kyrie de Josquin glosado’, Libro de cifra nueva, fol. 54r.

Venegas believed that his tablature could be a universal notation for the harp and vihuela, the other polyphonic instruments in use in Spain at the time. In the prefatory texts Venegas gives guidance to harpists and vihuelists. He provides no specific text to assist harpists read the tablature given its similarity to the keyboard but provides a woodcut diagram on fol. 3 (sic = fol. 4) showing the strings of the harp and the corresponding cifras, commenting also that harpists will sometimes need to omit notes when the texture requires it. This tablature continued to be used by harpists in Spain until well into the 18th century, with the addition of fingering symbols in later sources for guidance.20

Using Venegas’ tablature on the vihuela required some memorisation, but was not difficult, but there is no evidence to suggest that it gained acceptance among players. Of greater relevance was Venegas’ recommendation to keyboard players that they learn how to rewrite lute or vihuela tablature into his cifra nueva. He notes (using the term vihuela to mean both vihuela and lute) that, because ‘of the many eminent vihuela players, both foreign and Spanish, with different airs and ways of playing, it seemed to me that it would be good to open to keyboard and harp players the door to all the vihuela music that is printed in cipher.’21 He was aware of reality: at the time his Libro de cifra nueva appeared in 1557, only twenty keyboard books had been published in Europe, in comparison to some hundred books of lute tablature. To exemplify how it was done, he transcribed twenty works by lutenist Francesco da Milano, and vihuelists Luis de Narváez, Alonso Mudarra and Enríquez de Valderrábano into his book. As John Ward showed in his incisive study of these adaptations, Venegas did not simply transcribe the works from one notation to another: he modified them in various ways to become more idiomatic keyboard pieces, sometimes in ways that today might be considered questionable.22

The content of Venegas’ book completely justifies it being subtitled ‘for keyboard, harp and vihuela’. The case for Cabezón is not as simple. His extensive ‘Proemio’ completely ignores the harp and vihuela, save a few passing references, and most of the music in his tablature is far too complex for harp and vihuela without significant modification.23 Use of the phrase ‘for keyboard, harp or vihuela’ in the book’s title is therefore not tied to the contents of the book which appears expressly conceived for keyboard, a compendium written by the greatest organist known in Spain in the 16th century and posthumously published by his son.

Hernando de Cabezón had decided to publish a manuscript of his father’s music by at least September 1575 when he was granted licence by Philip II for ‘a book made by Antonio de Cabezón your father […] called Compendio de música, suitable for keyboard, harp and vihuela, and which you have arranged and put into tablature.’24 There is no evidence of the notational format used by Antonio de Cabezón for his Compendio, but evidently it was not written in tablature. It may have been written in a format such as that used in the Coimbra manuscripts written in score.25 Hernando de Cabezón notated it using Venegas’ tablature but with the addition of mensural rhythmic signs to give greater precision (Fig. 8). In May 1576, Hernando visited the printer Francisco Sánchez in Madrid to arrange the printing. He took a copy of Venegas’ book with him to show the printer what he wanted. The details are specified in the contract that Hernando signed with Francisco Sánchez on 29 May.26 Cabezón spelt out all the details of the typography and layout closely based on Venegas’ book. He left his copy of the book with Sánchez so he could refer to it as needed and required him to sign it as proof that he had seen it.

Fig. 8: Cabezón, Obras de música, fol. 37v.

In the printing contract, Hernando de Cabezón’s book is described as ‘un libro de Antonio de cauezon, su padre, de tecla y bihuela, recopilado y Puesto en cifra por el dicho hernando de cauecon’ thereby revealing that by this date he was thinking of it as for keyboard and vihuela. No other documentation concerning the printing is conserved between the signing of the contract and the publication of the book in 1578. Curiously, when the book appeared in print, the title page of the Compendio de música, as Antonio had originally named it, had been changed to Obras de música without apparent warning. Nowhere prior to publication is there mention of the Libro de música, and it is only on the title page that it is thus described together with the reference to it being for keyboard, harp and vihuela: Obras de musica para tecla arpa y vihuela. This change must have happened at the very last moment after the typesetting of the tablature. It was customary with books of this type to print the main corpus of the book first and then add the title page, table of contents, preliminary texts and errata later. In the book itself, the first page of tablature has the original title of the book ‘Compendio de Música de Antonio de Cabeçon’ in large type. Throughout the entire corpus of tablature, the recto side of each folio also has ‘Compendio de Musica’ as its header.

My suspicion is that very late in the printing process, Hernando de Cabezón changed his mind about the title. There is no way of knowing who may have persuaded him, whether the printer, somebody else, or even the author himself upon reflection. The title ‘Compendio de música’ has the ring of a theory treatise rather than an anthology of works to play and enjoy. In that respect, Obras de música sounds less pretentious and perhaps might have helped achieve sufficient commercial success to recuperate the cost of printing. Contrary to this, it is to be observed that in the version of the printing licence included in the book (on fol. [*2v]) the book is described as ‘vn libro intitulado Compendio de musica: el qual seruia para tecla, vihuela y arpa’, using the original title with the added reference to ‘keyboard, harp and vihuela.’ It seems that the reference here to the instruments may have been added to the printed version and may not have been included in the original version of the licence issued in 1575. Even if not the case, there is no evidence that Cabezón’s book was intended for any instrument other than keyboards, particularly the organ but also the clavichord. Quite simply, there was no interchangeable instrumental repertoire in 16th-century Spain for ‘keyboard, harp or vihuela.’ Even though it was clear that Hernando de Cabezón wished to perpetuate the memory of his renowned father, the venture does not appear to have been a success. Details of the law suit initiated by Hernando in 1585 to recover money from Madrid book dealer Blas Robles to whom he had entrusted the sale of the books indicates that there was little appetite in Spain for the music of a master who had been dead for over twenty years.27

Endnotes

Bibliography

Higinio Anglés, La música en la corte de Carlos V con la transcripción del ‘Libro de cifra nueva para tecla, harpa y vihuela’ (Alcalá de Henares, 1557) compilado por Luys Venegas de Henestrosa, 2 vols., Monumentos de la Música Española II, III (Barcelona, 1944; repr. 1965)

Willi Apel, The Notation of Polyphonic Music: 900–1600 (Cambridge, MA, 1942)

Gonçalo de Baena, Arte novamente inventada pera aprender a tanger (Lisbon: Germao Galharde, 1540), <https://imslp.org/wiki/Special:ReverseLookup/216087>

Gonçalo de Baena, Arte para tanger (Lisboa, 1540), edition and introductory study by Tess Knighton (Lisbon, 2012)

Howard Mayer Brown, Music in the Renaissance (Englewood Cliffs, 1976)

Hernando de Cabezón, Obras de música (Madrid: Francisco Sánchez, 1578) (RISM 158724), <http://purl.org/rism/BI/1578/24>

Vincenzo Capirola, ‘Ricercar otavo’, US-CN Case MS VM C. 25, The Capirola Lute Book (c. 1517), <http://ricercar-old.cesr.univ-tours.fr/3-programmes/EMN/luth/pages/notice.asp?numnotice=4>

Girolamo Cavazzoni, Intabvlatvra d’organo […] libro secondo (Venice [Girolamo Scotto], after 1543)

Andrés Cea Galán, ‘La cifra hispana: música, tañedores e instrumentos (siglos XVI-XVIII)’, Doctoral thesis, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, 2014

Antonio Corona-Alcalde, ‘The earliest vihuela tablature: a recent discovery’, in: EM 20 (1992), 594–600

Gerhard Doderer, ‘Os manuscritos MM 48 e MM 242 da Biblioteca da Universidade de Coimbra e a presenca de organistas ibéricos’, in: RdM 34, no. 2 (2011), 43–62

Richard Freedman, Music in the Renaissance (New York, 2012)

John Griffiths, ‘The Lute and the Polyphonist’, in: Studi Musicali 31 (2002), 71–90

John Griffiths, ‘Venegas, Cabezón y las obras “para tecla, harpa y vihuela”’, in: Cinco siglos de música de tecla española – Five Centuries of Spanish Keyboard Music, ed. Luisa Morales (Garrucha, 2007), 153–68

John Griffiths, ‘¿Fantasía o realidad? La vihuela en las Obras de Cabezón’, in: AnM 69 (2014), 193–214

Donald J.Grout, A History of Western Music (New York, 1960), (with nine subsequent editions by Claude Palisca and Peter J. Burkholder)

Alec Harman and Wilfred Mellers, Man and his Music (London, 1962)

Santiago Kastner, ‘Los manuscritos nºs 48 y 242 de la Biblioteca General de la Universidad de Coimbra’, in: AnM 5 (1950), 78–96

Tess Knighton, ‘A newly discovered keyboard source (Gonzalo de Baenas’s Arte novamente inventada pera aprender a tanger, Lisbon, 1540): a preliminary report’, in: Plainsong and Medieval Music 5 (1996), 81–112

Jean Michel Massing and Christian Meyer, ‘Autour de quelques essais musicaux inédits de Dürer’, in: Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte 45 (1982), 248–55

Michael Maul and Peter Wollny, ‘Introduction’, in: J. S. Bach, Weimarer Orgeltabulatur (Kassel, 2007)

Jessie Ann Owens, Composers at Work: The Craft of Musical Composition 1450–1600 (New York, 1997)

Jacob Paix, Thesavrvs Motetarvm: Newerleßner zwey vnd zweintzig herrlicher Moteten (Strasbourg: Bernhart Jobin, 1589) (VD16 ZV 26531), <https://mdz-nbn-resolving.de/details:bsb00031714>

Cristóbal Pérez Pastor, ‘Escrituras de concierto para imprimir libros’, in: Revista de Archivos, Bibliotecas y Museos, 3ª época, i (1897), 363–71

Gustave Reese, Music in the Renaissance (New York, 1954)

Tomas de Santa María, Libro llamado arte de tañer fantasía (Valladolid: Francisco Fernandez de Cordova, 1565), <http://bdh-rd.bne.es/viewer.vm?id=0000158382&page=1>

Francesco Spinacino, Intabolatura de lauto libro primo and Intabolatura de lauto libro secondo (Venice: Ottaviano Petrucci, 1507) (RISM 15075 and 15076)

Luis Venegas de Henestrosa, Libro de cifra nueva (Alcalá de Henares: Juan de Brocar, 1557), <http://bdh-rd.bne.es/viewer.vm?id=0000039213&page=1>

John Ward, ‘The Editorial Methods of Venegas de Henestrosa’, in: MD 6 (1952), 105–13

Johannes Wolf, Handbuch der Notationskunde, 2 vols. (Leipzig, 1913–1919)