Instances in Sixteenth-Century Keyboard Music Where Ornamentation and Changing Note Values Might Induce the Player to Vary the Beat

Domen Marinčič

How to cite

How to cite

Abstract

Abstract

Nicola Vicentino’s description of singers varying the beat in order to clarify the affect of the words and the harmony may seem to be relevant to certain keyboard music, all the more since sources point out that solo performers enjoy greater freedom than do ensembles. Tempo changes sometimes seem to be implied by striking differences between predominant note values in sections of a piece. One might expect shorter note values to be generally associated with a slower tactus, and longer note values with a quicker one, but some composers demand the opposite, so that the contrasts in the music are amplified rather than understated. Ornamented keyboard intabulations can occasionally be seen to imply textually and musically motivated tempo changes via noticeable variation in the density of ornamentation.

About the Author

About the Author

Domen Marinčič studied viola da gamba, harpsichord, and thorough bass in Nuremberg and Trossingen. He has performed extensively throughout Europe, in Canada, USA, China, Korea, and Vietnam, participating in more than 40 CD recordings for well-known labels. In 2021 he was appointed professor of historical performance practice at the Hochschule für Musik und Theater Hamburg.

Outline

Outline

Several sources from the second half of the 16th century mention changing the measure or varying the beat within pieces. One of the best known is Nicola Vicentino’s book of 1555 with its reference to vocal ensembles changing the measure when performing music in the vernacular.1 Here and elsewhere, we read about various things that would induce one to change the tempo, the most common being the affect, the sense of the words, and the harmony.2 The wording of such descriptions sometimes implies an association with rhetoric, and Vicentino draws an analogy with the orator who moves his listeners by speaking ‘now loud and now soft, now slow and now fast’.3 While such changes helped to express the affect, they also met the need for variety, which is another important factor mentioned in connection with tempo changes by Vicentino, his Neapolitan contemporary Giovanthomaso Cimello, and several later authors.4 We must therefore bear in mind – and this is perhaps especially important in the case of instrumental music – that the beat could sometimes change within a piece purely in order to provide variety, notably in instances when musical material is repeated. It seems that the use of different note values and proportional signs alone was not considered sufficient for expressing affect and providing variety in performance. The speed of the tactus was perceived as an important parameter in its own right, operating together with the other components.

The title of this article comes from a particularly intriguing text which mentions tempo flexibility in keyboard performance. Its author, Hanns Haiden, son of the music theorist Sebald Heyden, was organist at St. Sebald and St. Egidien in Nuremberg between 1567 and 1585. In 1575 he invented the Geigenwerk, a stringed keyboard instrument capable of sustained sound, graded dynamics and controlled vibrato. The passage in question appears in the second German edition of the Musicale instrumentum reformatum, a small book that he wrote in praise of this instrument, published in 1610, when he was in his mid-seventies. Among the advantages of the Geigenwerk, on which ‘one alone can achieve that which would otherwise require five or six violin players’, Haiden lists the possibility of varying the beat. He goes on to point out a telling difference vis-à-vis string consorts:

Secondly, the player can change the measure as he pleases, guiding it now slowly, now again quickly, which is also required in order to move the affections. Several violinists together, however, do not do this simultaneously nor can they achieve such good ensemble.5

Haiden does not specify any particular repertoire in which he expects keyboard players to vary the beat. While this practice was considered necessary for expressing affect, he also seems to suggest that there can be other reasons for changing the measure, or that it can be an end in itself. Such changes do not appear to have been fixed or predetermined and were left to the performer’s discretion.6 Furthermore, solo performance is described as being more flexible than ensemble playing. Perhaps Haiden would also have desired more flexibility, or better ensemble, from string consorts? His explanation for a depiction of a triumphal chariot glorifying music, dated 1607, shows the Mensur to be the whip in the hands of the allegorical figure representing the faculty of hearing, which makes the horses run quickly or slowly. Other elements positioned around the coachman include a sharp mind, nature, affect, and variety.7

Michael Praetorius cites the first part of Haiden’s statement in the chapter on the Geigenwerk in the second volume of his Syntagma musicum, replacing the remark concerning the limited flexibility of string ensembles with a recommendation that the practice of varying the measure ‘can similarly be observed on other instruments’.8 This brings the suggestion outside the context of Haiden’s argument and thus the reader wonders why Praetorius should associate tempo flexibility with this particular instrument and fails to mention it anywhere else in his book on organology.9 At the same time, his comment does suggest that the practice of changing the tempo should perhaps be applied more widely in instrumental music.

Note Values and Tempo

It is likely that the tempo would often have changed between one section and another of a piece, where these differ as regards their predominant note values. Such differences often coincide with changes in text, harmony and affect, but their implications for the tempo are not always clear.

The choice of tempo depends to some extent on the note values found in a piece, as well as on the types of rhythm and the levels at which they operate. Bartolomeo Ramos de Pareja explains in 1482 that if a piece has too many short notes, performers place the mensura on the semibreve or minim – although, in theory this should in fact be on the breve or semibreve.10 Such a shift in the level of the mensura implies a slower tempo for the semibreve or minim. A similar type of shift occurred later in the case of the note nere madrigals that began to appear around 1540. The emergence of this new style opened the door for composers to vary the compositional tactus, meaning harmonic and contrapuntal rhythm, between longer and shorter units within a piece, providing a variety of rhythmic and connotative devices to meet the affective demands of the poetic text.11

Contrary to the principle of choosing a slower tempo when the music features many short notes, Luis Milán demands in 1536 that in certain of his fantasias for vihuela the performer should provide more contrast between the chords, which he notates in minims, and the runs, notated in quavers:

And in order to play them with their natural style you need to direct yourself in the following way: all that might be in chords should be played with a slow beat and everything that is redobles [diminutions] should be played with a fast beat, and one should pause a little at each fermata.12

This approach, which Milán limits to very specific pieces, exaggerates the contrast between slow and fast and can be used to amplify differences in affect. Unwritten changes of measure in vocal music could have produced a similar result. Vicentino complains about singers ruining a sad passage, where his comments would suggest a slower beat on account of the affect, by showing off their talent for embellishment. He also mentions that he has heard singers make the opposite mistake by failing to show off their talent when a composer prescribes a cheerful passage with diminutions, possibly singing such a passage too slowly.13 This implies that sad music will normally have longer note values and a slower beat, while cheerful music may feature lively diminutions in shorter note values and a faster beat.

Variable Note Values

In the chapter on the division of the tactus and its administration in his Prattica di musica of 1592, Lodovico Zacconi explains:

Different tactus may be faster or slower, according to the place, time, and occasion, because this variety does not create any defect in music, as long as the one who gives the tactus knows how to contract and stretch it and make the above-mentioned rising and falling motions equal, and not altered.14

On account of a common misunderstanding of the terms ‘stringere’ and ‘allargare’, which in this context refer to the falling and rising motion of the tactus in analogy to the systole and diastole of the human pulse,15 this passage has traditionally been interpreted in the scholarly literature as describing tempo changes, but it remains unclear whether Zacconi is referring to varying the beat within pieces. He writes that observing the common tactus is easy in itself, but that compositions with diminutions sometimes make it difficult for the time-beater to keep time. In the chapter on the maestro di cappella, he repeatedly criticises time-beaters who slow down the tactus because of the difficulty of the figure (i.e. written notes), endeavouring to make them easier for the singers. In his opinion, this turns one note value into another, disregarding the composer’s intention:

In order to be understood by all, so that this blameworthy abuse may be completely removed from the present state of affairs, and this error may be eliminated completely, I say that there are some administrators of tactus who, when directing it in some difficult songs where there is a great abundance of quavers, in order to enable the singers to count them better and with less difficulty, slow down the said tactus so much that they make them sing as crotchets, and do not perceive that if the composer who has composed them had wanted them to be sung as crotchets he would not have made them quavers. It is, however, good that they are recognised by the listeners as quavers like they have been made by the composer. […] The figures may well be sung differently, for the composer is obliged to compose them according to the order of the signs and rules of tempo which he uses, and the singer to sing them as he pleases; for who can claim that the semibreve which is commonly worth one tactus should not be sung for a breve or longa, giving a multiplied value to each? Or to diminish them by half and make them move twice as fast under the same tactus? But just as this manner of singing would be a caprice, an extravagant manner, not to say reckless, so also changing quavers into crotchets is not praiseworthy, for in every way that one can sing and turn them, the composer who composed them could have formed them in this way if he wanted.16

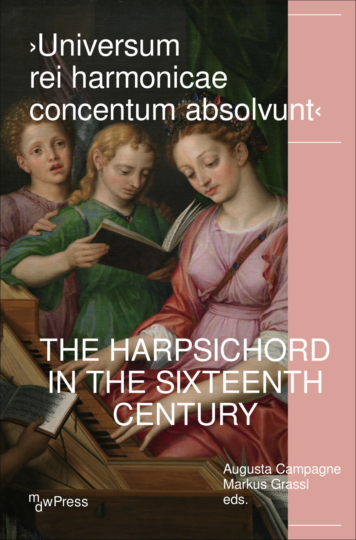

Notwithstanding such claims, there seem to have been occasional dilemmas regarding the choice of note values among composers and editors. A number of pieces have survived in more than one version, with one source showing halved or doubled note values in respect of the other. Sometimes such differences only affect a section of the piece, often the one with the shortest note values. At the end of a lute fantasia by Pietro Paolo Borrono published in 1546 and transcribed in Ex. 1 the composer provides an alternative, ossia version of the five bars containing semiquavers, which are the fastest notes in the piece and occur very rarely in this repertoire. In an accompanying comment Borrono explains the reason for this:

Since in the above fantasia there are some measures that learners may find difficult, I have written the same measures in a different and easier tempo, reducing the semiquavers into quavers, and the quavers into crotchets.17

It has been suggested that this represents only a different manner of notating the passage in question, but such an explanation seems questionable.18 Rather, one wonders how ‘learners’ understood this message and whether something similar may have applied elsewhere as part of performance pratice, even if it depended on the proficiency of the player.

A similar intervention was undertaken in the revised edition of a collection of bicinia published by Pierre Phalèse. The thirteen textless bicinia by Orlando di Lasso had first been published more than thirty years earlier and had meanwhile also been issued by Phalèse in their original form in 1590. In Phalèse’s new edition of 1609, all note values from the middle onwards were doubled in seven of the thirteen pieces.19 In their original form the pieces in question display a relatively wide range of note values, starting slowly in minims, accelerating during the course of the piece and ending with lively quaver movement. The revised versions are not without problems of musical consistency, but they achieve a steadier basic pace and a greater sense of unity, with much less contrast in note values. Since these are didactic pieces, the changes have possibly been introduced with beginners in mind. One wonders whether the beat would have varied in this type of music: a collection of bicinia published by Seth Calvisius in 1599 finishes with a set of rules for singing, among which we find the indication sometimes to accelerate and sometimes to slow down the tactus for reasons of harmony and text.20

Ex. 1: Pietro Paolo Borrono, Fantesia dell’eccellente P.P. Borrono da Milano, bb. 165–201.21

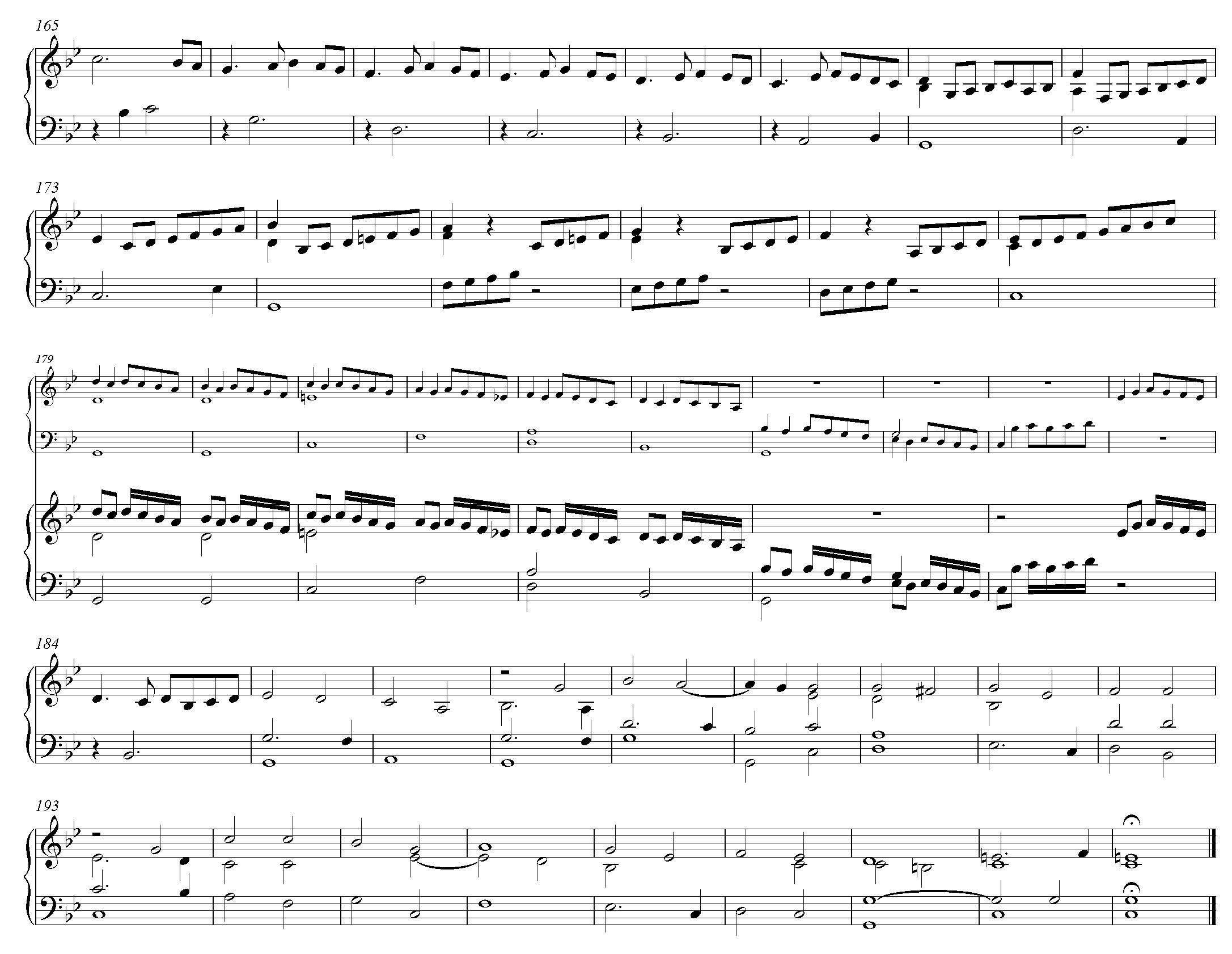

The opposite type of revision, one doubling the speed of a passage, is probably seen in the introductory section to one of the best known keyboard fantasias by William Byrd, as shown in Ex. 2. The version in the Fitzwilliam Virginal Book changes the quaver runs in the last few bars into semiquavers. A scribal error is not plausible since the writing in both sources is neat and clean, and the rhythms all add up. The difference is perhaps indicative of the improvisatory nature of the flourishes. For the performer this can imply greater flexibility, or perhaps a non-proportional acceleration in relation to the quaver scales occurring earlier. On the other hand, semiquaver passages return later in the work, and one might speculate that this newly established correspondence reflects Byrd’s later thoughts.22 The two versions may have been meant to sound different, since the version in semiquavers retains only one of the three ornament signs, but this does not eliminate the possibility of performers adjusting the tempo at the point where semiquavers start.

Despite the differences found in these variants, all of them – Borrono, Lasso, and Byrd – can make musical sense when performed without noticeable tempo changes. They do, however, raise doubts about the reliability and definitive quality of musical notation. We might, after all, imagine a situation in which only the alternative versions of pieces such as Borrono’s or Lasso’s survive.

Ex. 2: William Byrd, Fantasia C2, BK25, bb. 6–15. Comparison of versions in My Ladye Nevells Booke and The Fitzwilliam Virginal Book.23

A literal interpretation with a more or less steady, unchanging beat seems very improbable in two of Claudio Merulo’s toccatas preserved in the so-called Turin Tablature. Copied between 1637 and 1640 and notated in ‘new German organ tablature’, these are believed to be primitive versions, perhaps from as early as 1567, of toccatas published in 1598 and 1604 respectively. The large collection in Turin contains both versions of these two toccatas, the earlier versions having been copied from an unknown source and the later ones from Merulo’s printed books of toccatas. Besides many differences in the passagework, the first of these toccatas, no. 18 in the manuscript and no. 8 in the 1598 print (see Ex. 3), evidences a revision that is suggestive of a tempo change between sections. The earlier version in Turin includes a short ricercar-like section notated traditionally in minims. While this section was later removed, the transition to the subsequent section remained, albeit with the quaver figuration changed into semiquavers. It thus seems likely that the imitative section in long note values and the subsequent transition, as notated in the earlier version, were intended to be played at a faster tempo than the rest.

Ex. 3: Comparison of Claudio Merulo, Toccata di Ms. Claudio, no. 18, from the Turin Tablature, and Quarto Tuono: Toccata Ottava, from Toccate d’intavolatura d’organo […] libro primo, bb. 52–57.24

The situation is clearer still in the next toccata, no. 19 in the Turin Tablature and no. 8 in Merulo’s second book of toccatas. As shown in Ex. 4, the imitative section starting at b. 45 is retained in the 1604 print, albeit in a revised version with halved note values. All imitative sections in Merulo’s printed toccatas are notated in this manner, in crotchets rather than minims, producing an overall smaller range of note values and less rhythmic contrast between sections. Unless the two surviving versions were intended to sound very different in terms of tempo, Merulo must have expected considerable tempo changes at the transitions from one section to another in at least one of these versions.

We can also consider the possibility that Merulo’s idea of the degree of contrast between sections evolved over time, and that rapid passages were later played more slowly, while imitative sections became faster, than when he first wrote down the toccatas. Such passages could, for example, have slowed down if the harpsichord was exchanged for the organ. One detail that would support the idea of a slower tempo for the semiquaver passages in the later version is the intensification of the ornamentation and the introduction of occasional demisemiquavers. Moreover, both versions of the imitative section contain trills in semiquavers. Whereas the surrounding notes are halved in the print, many of these trills remain written as semiquavers, only with fewer repercussions, and solely the short tremoletti are transformed into demisemiquavers. It is more likely, however, that the additional scales and repercussions in demisemiquavers found in the print fall within the scope of the original performance practice and that similar florid passages could have been improvised by expert players. It has been suggested that the early versions of these toccatas may have been copied from an early print, announced in 1567 and now lost, and that the intensification of ornamentation was enabled by the change in printing technology from movable type to copper plates.25

Ex. 4: Comparison of Claudio Merulo, Toccata del Ms. Claud., no. 19, from the Turin Tablature, and Ottavo Tuono: Toccata Ottava, from Toccate d’intavolatura d’organo […] libro secondo, bb. 42–50.26

While the early versions of these toccatas feature greater rhythmic contrast between sections, this contrast is provided mainly by the diminutions. With all figurations, trills, and scales removed, the early versions would appear to be more unified, with slower harmonic movement retained throughout the pieces. Yet in performance they seem to require more obvious tempo changes than the revised versions, where the imitative sections are notated in crotchets.

Taking Additional Time for Ornamentation

Several late 16th-century treatises discourage the momentarily slowing down of the beat in order to perform diminutions:

I say that it is difficult to keep the diminution in tempo, and this is of greatest importance for everyone who follows this profession of making diminutions with all kinds of instruments. Therefore, let everyone, in their study, strive to beat time, and never study without this order, and become accustomed to the tactus; for to do otherwise would not be a good thing.

(Girolamo Dalla Casa, Il vero modo di diminuir [1584])27

It is good, however, to avoid them [parallel fifths and octaves] as much as possible, and anyone will do it easily with attention to time and measure, because to tell the truth, however swift, skilful and distinct the ricercata may be, if perchance it is not achieved in time, it loses all its elegance.

(Riccardo Rognoni, Passaggi per potersi essercitare Nel Diminuire [1592])28

One should never give way to any of the singer’s voices, because giving way to the desires of this or that singer to give them time to fill the songs with graces makes the harmonies weak and slow, and the [other] singers find it unreasonably tiresome, hating that slowing down and unwelcome intervention.

(Lodovico Zacconi, Prattica di musica [1592])29

Some are in the habit, in order to accommodate passaggi in their own way, of holding a one-beat note for two or three beats, for what reason I do not know: what I do know is that it is more praiseworthy when making passaggi to remain bound to the correct pulse, as written in the part, except at the end, that is on the final note.

(Giovanni Battista Bovicelli, Regole, passaggi di musica [1594])30

While Dalla Casa and Rognoni may be seen to focus on correct time-keeping in a didactic context, Zacconi and Bovicelli seem to criticise existing practices. Differentiation between solo and ensemble performance is also possible, as suggested in the discourse sent by Giovanni de’ Bardi to Giulio Caccini around 1578. Towards the end of his letter Bardi criticises certain ensemble singers:

There are also others who are so complacent when performing passaggi that they disregard the tactus, breaking it down and stretching it out so much that they do not allow their companions to sing in a good manner at all.

A few lines later, Bardi writes that different criteria apply to solo performance:

When singing alone or to the lute, harpsichord, or other instrument, one may contract or stretch the tactus at will, as it is up to the singer to lead the measure according to his judgement.31

As regards the question of flexibility of tempo, Bardi, like his contemporary Haiden, sees a considerable difference between solo and ensemble performance. While stating that the solo performer may vary the beat ‘à suo piacere’, or ‘nach seinem selbst gefallen’, they both imply that such practices may cause problems in an ensemble. Whereas Haiden mentions the requirement to change the measure to express affect, Bardi criticises ensemble singers for slowing down the beat for ornamentation. Bardi does not seem to be criticising simple tempo changes: such passaggi seem to have demanded a tactus which was either much too slow or too irregular and unpredictable for other ensemble members to follow. While he does not say whether in solo singing the beat would also have varied on account of diminutions, this is perhaps not unlikely.

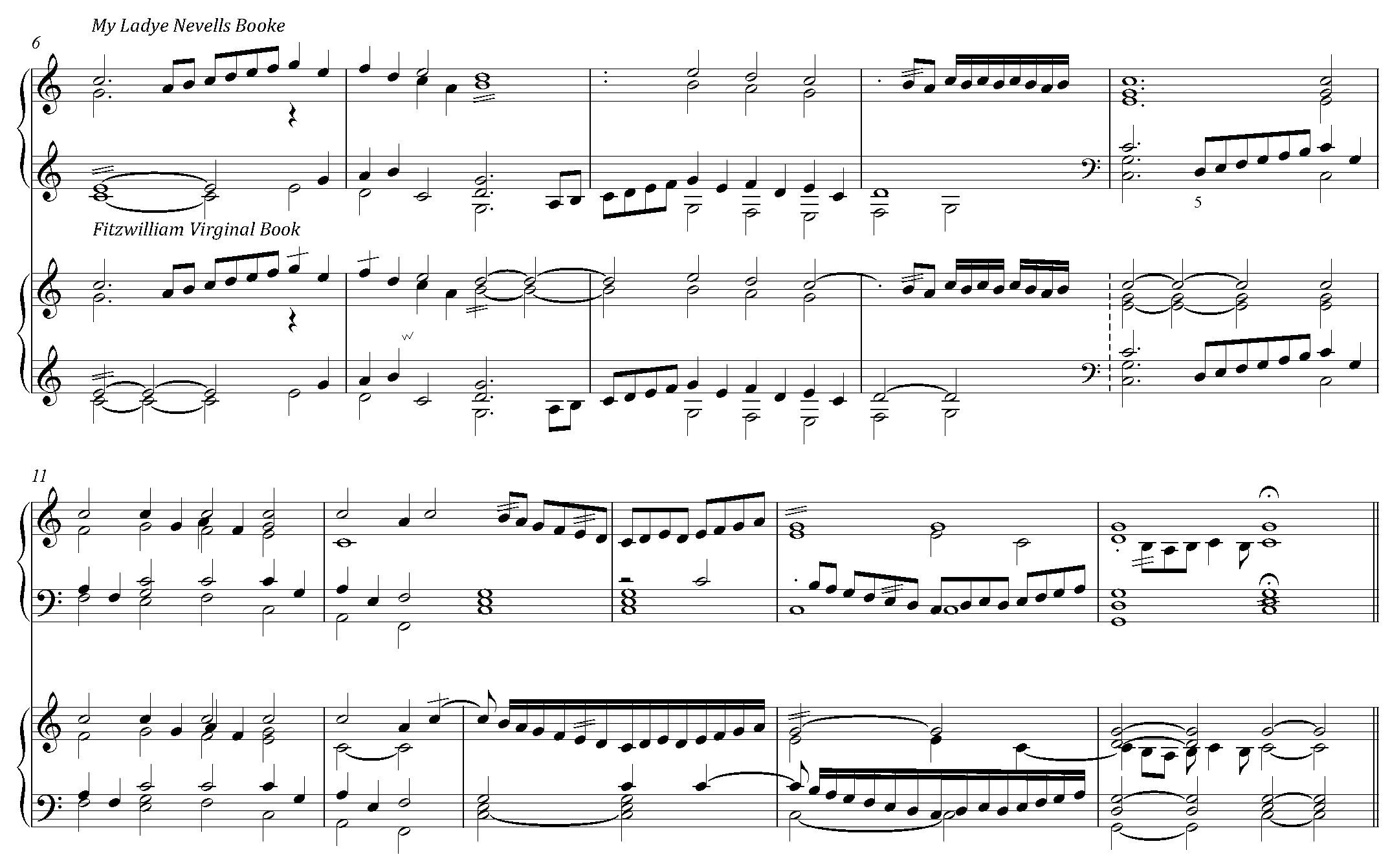

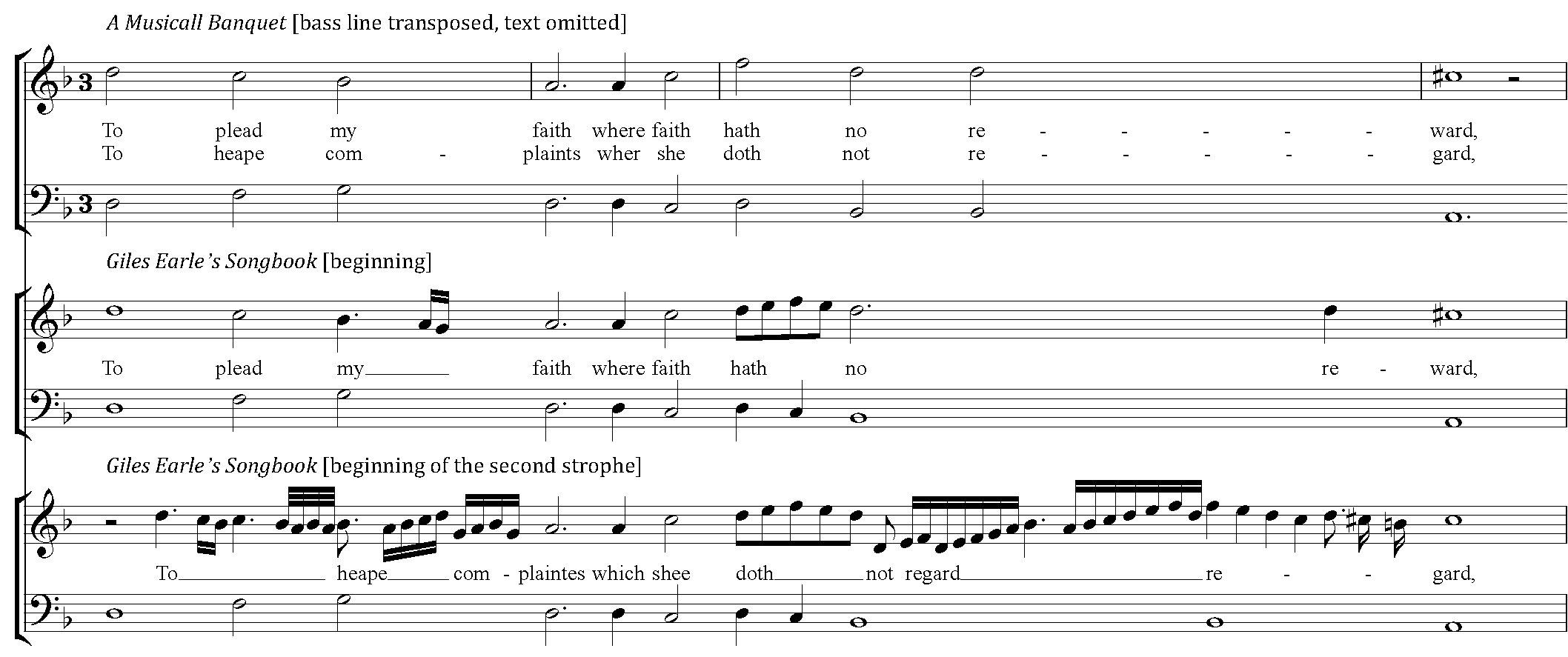

Ex. 5: Daniel Bacheler, ‘To Plead My Faith’, bb. 1–4. Comparison of versions in A Musicall Banquet (1610) and Giles Earle’s Songbook (c. 1615–26).32

Cases where the beat has to be suspended or slowed down momentarily in order to accommodate written-out ornamentation at cadences and elsewhere are especially common in English solo songs of the early 17th century, among which we find ornamented versions of songs by Giulio Caccini.33 Sometimes, in respect of the unornamented original versions, notes are prolonged. In Ex. 5, which shows three versions of the opening phrase of a song by Daniel Bacheler, the penultimate note is doubled in length at the written-out repeat to provide more time for cadential diminution.

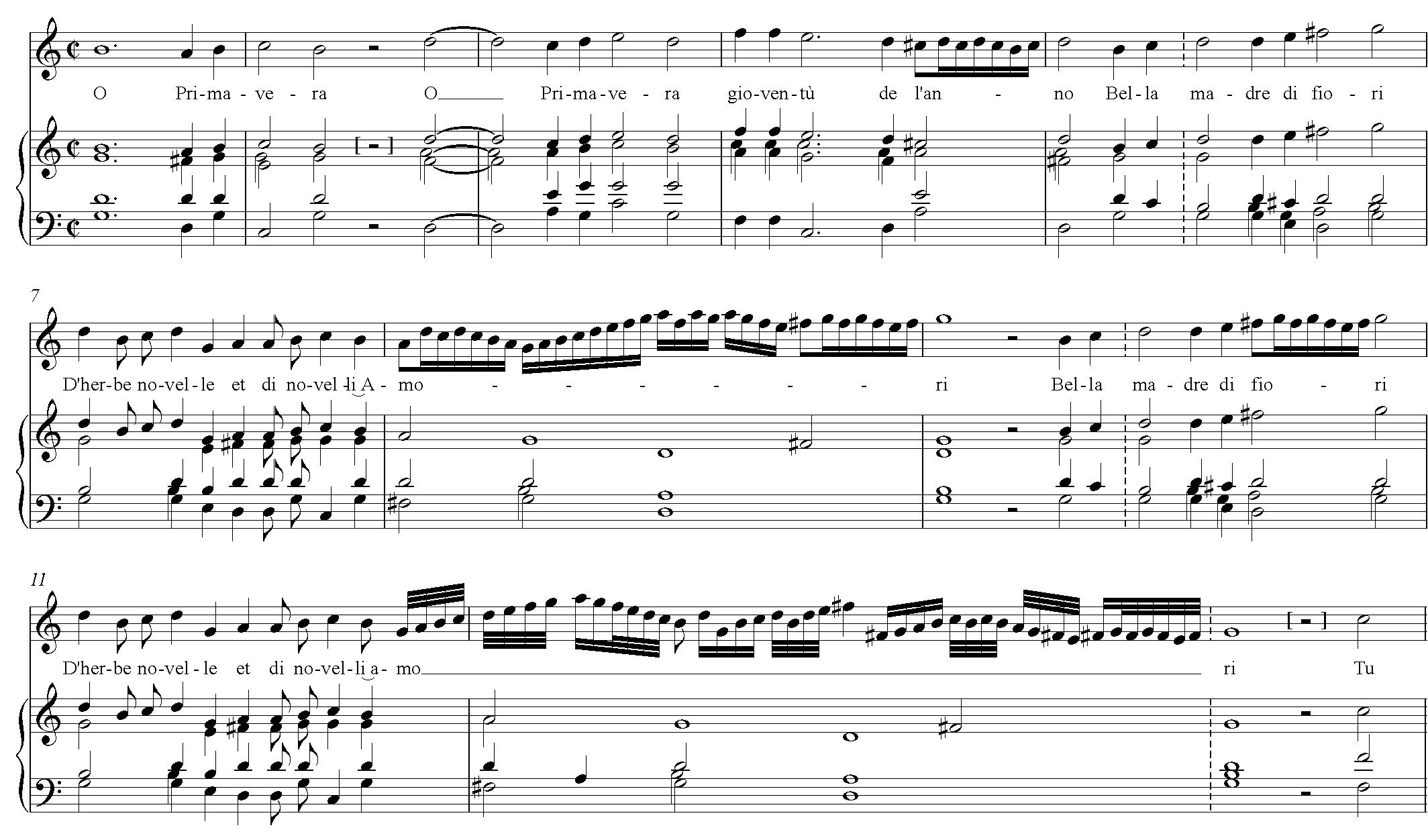

Sometimes, diminutions are carefully rhythmicised to fit into the underlying structure, but their density and speed might be a reason for performers to slow down considerably. See, for example, b. 12 of Ex. 6, taken from Luzzasco Luzzaschi’s madrigals for one to three voices and keyboard, printed in 1601 but probably written in the 1580s.

Ex. 6: Luzzasco Luzzaschi, ‘O Primavera’, bb. 1–13.34

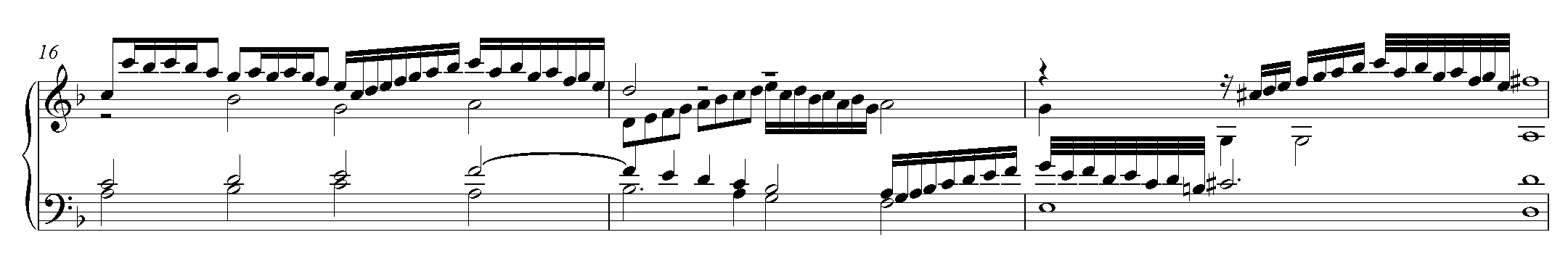

Ex. 7 shows an excerpt from Jacques Arcadelt’s madrigal Ancidetemi pur in an intabulation by Ascanio Mayone published in 1603. The figure present in the first two bars subsequently appears in halved note values, perhaps mainly in order to fit it into the rhythmical structure of the original madrigal. A literal interpretation is very unlikely, and the cadence in b. 18 would possibly been slowed down to half tempo.

Ex. 7: Ascanio Mayone, Ancidetemi pur (after Jacques Arcadelt), bb. 16–18.35

Such practices must have had their roots in improvised ornamentation. In the passage quoted above, Bovicelli mentions that some performers double or triple the length of the beat so that they can sing the diminutions ‘a modo loro’, implying a personal style and possibly either questionable taste, incompatibility with other ensemble members, or both. He considers it more praiseworthy to stay in the right time as written, except for the penultimate note at the very end. Throughout his treatise on diminution, Francesco Rognoni gives many examples of cadential passaggi that are two or more beats longer than the originals. He seems to be in agreement with Bovicelli, since these instances are all limited to final cadences.36 Examples such as the ones given above suggest, however, that, at least in solo performance, some practitioners considered taking more time or slowing down for ornamentation to be acceptable at cadences within a piece.37

Tempo and the Density of Ornamentation

Noticeable variations in the density of ornamentation, or even the presence and absence of diminutions in different sections of a piece, may perhaps indicate tempo changes intended by the composer. Their actual interpretation must sometimes remain open to question, since diminutions may demand either a slower beat or a livelier one, depending on the context. Vicentino’s criticism of singers for adding inappropriate diminutions to sad passages does not mean that all slow music must be devoid of passaggi. On the contrary, a slow beat can enable more florid ornamentation, while lively sections in a faster beat may provide less opportunity for diminution.

Girolamo Frescobaldi, Luzzaschi’s pupil, draws an analogy between keyboard toccatas and modern madrigals, where the beat would have varied according to the affetti, or meaning of the words. In a separate clause, he also makes it clear that he expects the tempo to be adjusted to the ornamentation both in his partitas and in his toccatas, suggesting a broad tempo for those variations or toccata sections that feature passaggi and affetti.38 It is possible that some earlier composers likewise anticipated certain tempo changes, adding more diminutions when a slower beat provided more time. We might be able to reconstruct some of their ideas of tempo differentiation on the basis of written-out ornamentation, especially in intabulations of vocal music where tempo changes may have been motivated by the sense of the words. Such a practice is easier to argue on the basis of notation than the opposite possibility of heightening the contrast between passages notated in shorter or longer note values.

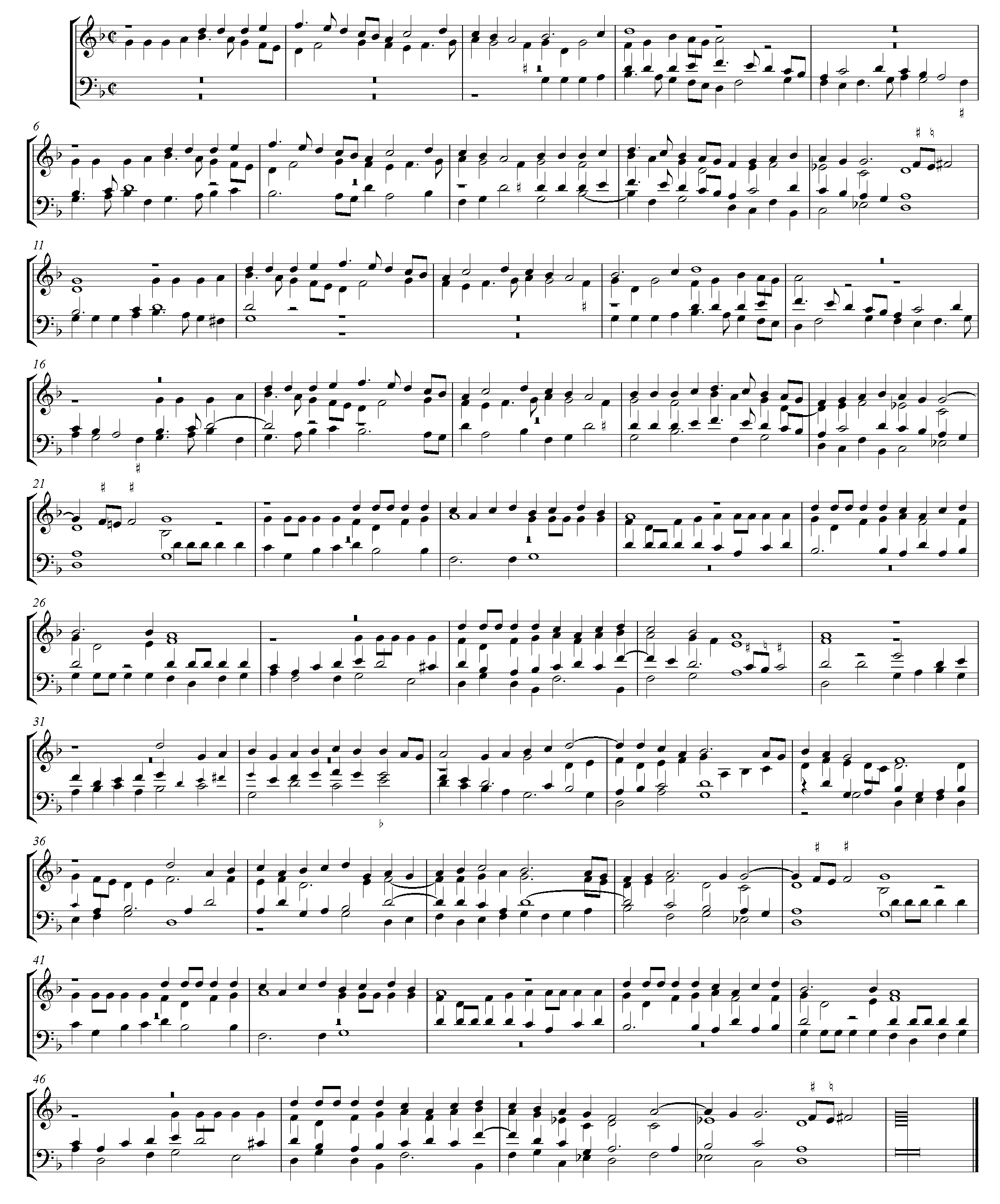

The appendix reproduces four complete pieces from late 16th-century Venice with hypothetical suggestions for tempo changes. Each of them belongs to a different genre: an intabulated madrigal, a motet with diminutions, a keyboard canzona, and a ricercar.

Andrea Gabrieli’s Ricercar Quinto Tono, published posthumously in Il terzo libro de ricercari of 1596 (see Appendix 1), features a striking contrast between ornamented and unornamented polyphony, with diminutions being completely absent in the second half of the piece. This would seem to make more sense if the tempo from the middle onwards, for example from the fifth appearance of the second subject at the end of b. 50, was expected to be noticeably faster in performance. A similar situation with a completely unornamented final section is found in those two Gabrieli ricercars that finish in triple time and where the change of measure is made obvious by the new time signature.39

Such quickening of the beat in a piece is described as being appropriate for motets, madrigals, and canzone villanesche, in an undated manuscript by Vicentino’s contemporary Giovanthomaso Cimello. He writes that such variation is more pleasing and entertaining.40 Nevertheless, such a tempo change is difficult to prove. The lack of ornaments in the second half of Gabrieli’s ricercar may be a deliberate effect, perhaps meant to provide variety. It is after all connected to the compositional design: while diminutions are almost invariably introduced in moments where the subjects are absent, the second subject is continuously present in one part or the other throughout bb. 43–93.

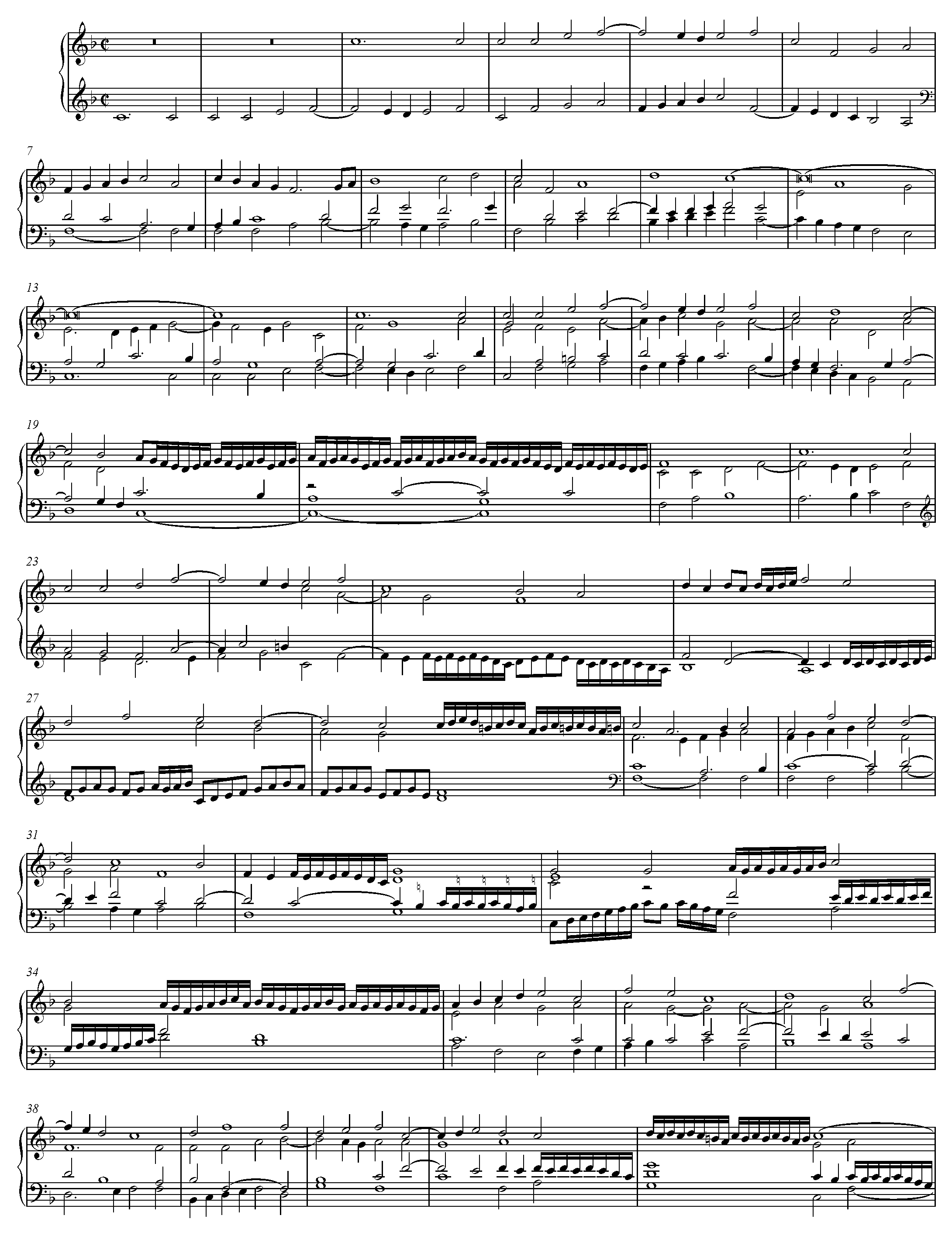

A change towards a quicker tempo may be suggested by the distribution of the ornamentation in Andrea Gabrieli’s intabulation of Cipriano de Rore’s famous madrigal ‚Anchor che col partire‘, published in the same collection as the Ricercar del quinto tono and given in Appendix 2. In the second half of the piece the ornamental figures are far fewer and much simpler. One could argue that the unornamented sections do not lend themselves to diminution, but this is disproved by the version of Gabrieli’s intabulation published in Bernhard Schmid’s Tabulatur Buch (Nuremberg: Lazarus Zetzner, 1607), where the ornamentation is distributed more or less evenly throughout the piece.41 A tempo change at the end of b. 18 seems a possible explanation for the lack of diminution, especially since it is supported by the affect of the text, attributed to Alfonso d’Avalos. The change occurs after a melancholy and tender opening, at the point when the lover assumes a more active role: ‘And thus a thousand thousand times a day I would like to part from you’. A different affect is already underlined by the use of shorter note values in Rore’s original, and a quicker beat would heighten this contrast despite reducing the difference between note values on the surface of Gabrieli’s ornamented version.42

It is of course also possible for a performer to introduce additional tempo changes and to return to a slower beat in both occurrences of the passage that speaks of sweetness (‘Tanto son dolci gli ritorni miei’). These moments are reminiscent, both textually and musically, of the section at the end of the first half (‘Tant’ è il piacer ch’io sento’). Since the one is ornamented and the other is left without any diminution, one could draw the conclusion that their tempi must be different, but a resumption of the original slow tempo for the ‘returns’ can provide additional variety. In this way the piece will have four tempo changes and three varying combinations of tempo and movement: 1) slow sections in long note values without passaggi, 2) ornamented slow sections, and 3) sections in a faster beat without diminutions and only occasional ornamental figures. Sections for which a faster tempo is suggested are marked in red in both the following text and the music given in Appendix 2.

|

Anchor che col partire Io mi senta morire, Partir vorrei ogn’hor, ogni momento, Tant’ è il piacer ch’io sento De la vita ch’acquisto nel ritorno. E cosi mille’e mille volt’il giorno Partir da voi vorrei, Tanto son dolci gli ritorni miei. E cosi mille’e mille volt’il giorno Partir da voi vorrei, Tanto son dolci gli ritorni miei. |

Although in parting I feel myself dying, I would like to leave every hour, every moment, So great is the pleasure that I feel From the life that I gain in returning. And thus a thousand thousand times a day I would like to part from you, So sweet are my returns. And thus a thousand thousand times a day I would like to part from you, So sweet are my returns.43 |

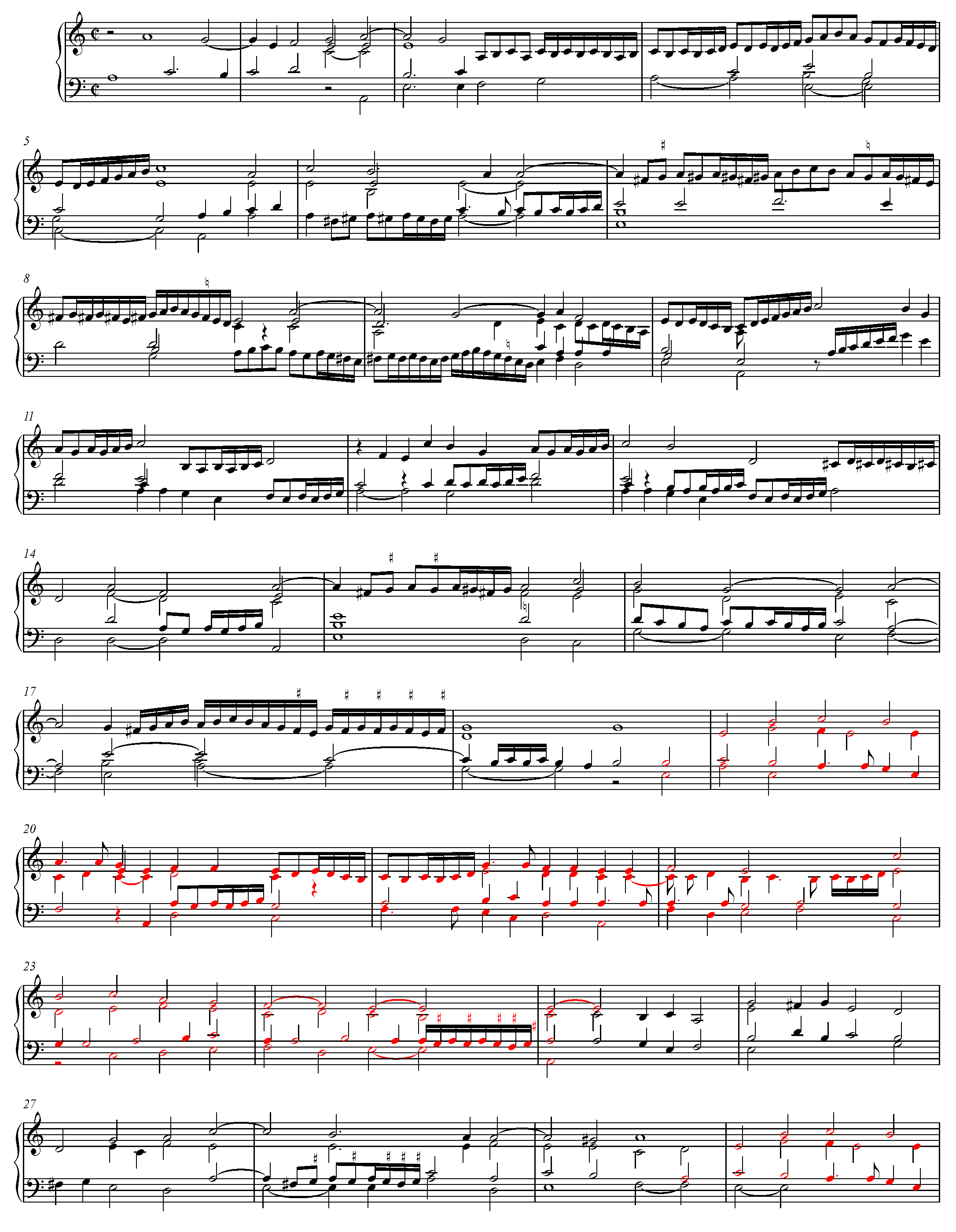

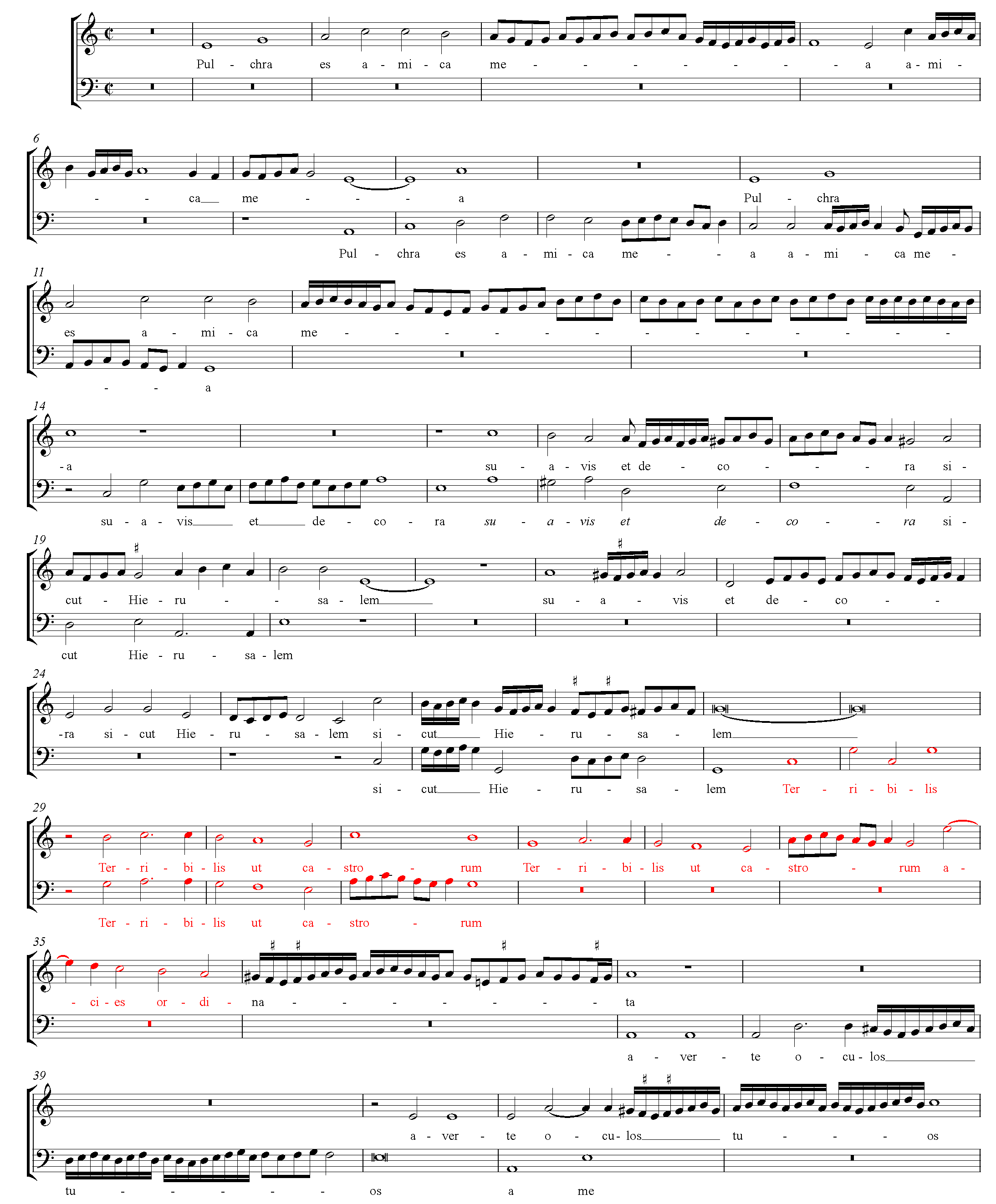

Giovanni Bassano’s ornamented version of Palestrina’s motet ‘Pulchra es’, published in 1591, can likewise be interpreted by considering the poetic text. Bassano provides texted diminutions for the two outer voices, reproduced in Appendix 3. In two sections found in the second half of the piece (bb. 29–35 and 44–55), he avoids diminutions in semiquavers, with the exception of the cadence in b. 36, which ends the first of these sections. From a purely musical viewpoint it may seem unusual, or even disappointing, to end the piece with diminutions in quavers, and not with a more profusely ornamented cadence such as the one mentioned above. On the other hand, performers might accept this slower movement as being suitable for the end of the piece. A viable solution to the problem of finding the appropriate tempo and movement is provided by the text, which is an excerpt from The Song of Songs:

|

Pulchra es, amica mea, Suavis et decora sicut Hierusalem Terribilis ut castrorum acies ordinata. Averte oculos tuos a me, Quia ipsi me avolare fecerunt. |

Thou art beautiful, O my love, Sweet and comely as Jerusalem, Terrible as an army with banners. Turn away thine eyes from me, For they have made me flee. |

The third line, ‘Terrible as an army with banners’, provides a strong contrast to the sweetness of the beginning. This passage is today considered to be an unfortunate Latin mistranslation of the Hebrew original,44 but, as it stands, it might imply a more forceful performance, perhaps with a faster beat. Since the movement in Bassano’s diminution is noticeably slower at this point, a faster beat might in fact have been expected until the ornamented cadence in b. 36. A faster tempo is more obviously implied by the final line, ‘for they have made me flee’. One would expect a faster movement, but Bassano avoids semiquavers until the very end. His diminutions enable a faster beat in both of these sections.

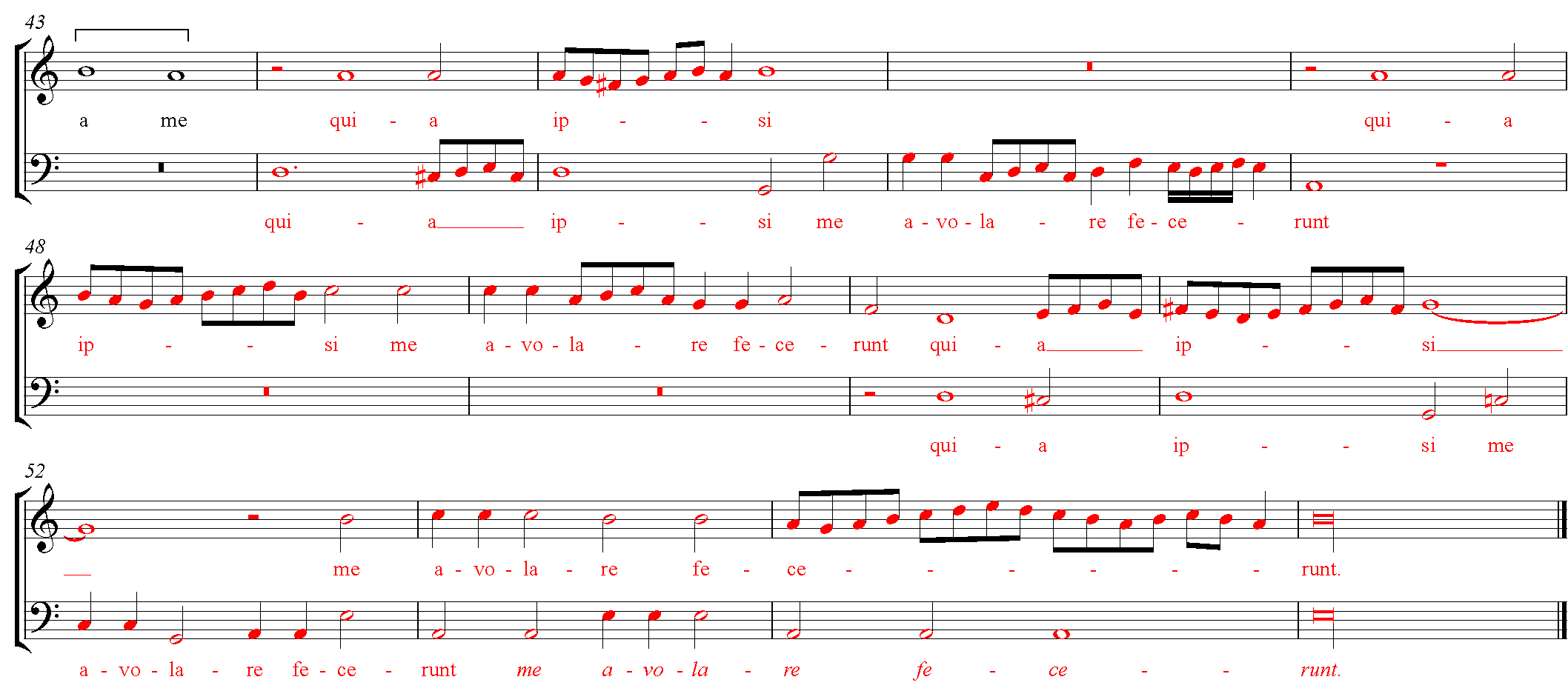

The final example is a canzona by Claudio Merulo. An ensemble version of this piece, by the title of L’Olica, appeared in a collection of canzonas of 1588 and is given in Appendix 4a. At first glance this version seems somewhat uniform, with no obvious change of note values from beginning to end. Merulo’s ornamented intabulation, published posthumously as La Radivila and shown in Appendix 4b, may shed light on tempo changes that he expected. We find a repeated section where diminutions are largely avoided and remain reserved for the final cadences (bb. 21–29 and 40–48). The character of this section with its energetic canzona motifs contrasts with the beginning of the piece, and a faster tempo seems appropriate.

Conclusion

While the changes of tempo suggested for the last three pieces can also be employed when performing the unornamented originals, they are hypothetical and by no means obligatory; the pieces would surely have been approached in various ways by musicians of the period. On the other hand, one can also imagine tempo changes in addition to the ones presented, especially since they are relatively simple: a single change in the ricercar, four changes in the intabulated madrigal, and three changes in both the ornamented motet and the keyboard canzona. They all occur in the middle of pieces, after the initial tempo has been well established, and can respond to the need for variety. Such tempo changes can easily be realised in an ensemble and do not seem to correspond to Haiden’s description of keyboard soloists changing the measure in ways that would be impracticable for a group of string players. Additional adjustments of tempo may, for example, be employed at the ornamented cadences.

Such observations may nevertheless be useful to modern performers, many of whom remain unaware of these possibilities. Tempo changes provide more variety: they can help to hold the listener’s attention, and, when they are recognised as such, to contribute to the communication between performers and their audiences. While highlighting changes of affect, they can also clarify the musical and poetic form, elucidating certain compositional choices. Furthermore, they enable the performer to introduce greater contrasts by including tempi that are slower or faster than is viable when the tempo remains unchanged throughout a piece. Several of these aspects are confirmed by contemporary writers. Vicentino explains:

A composition sung with changes of measure is pleasing because of the variety, more so than one that continues on to the end without any variation of tempo. Experience with this technique will make everyone secure in it. You will find that in vernacular works the procedure gratifies listeners more than a persistent changeless measure.45

Appendix 1

Andrea Gabrieli, Ricercar del quinto tono, from Il terzo libro de ricercari (Venice: Angelo Gardano, 1596), fols. 7r–10r. Online: <https://doi.org/10.3931/e-rara-55399>.↩︎

Appendix 2

Andrea Gabrieli, ‘Anchor che col partire’ (after Cipriano de Rore) from Il terzo libro de ricercari (Venice: Angelo Gardano, 1596), fols. 34r–36r. Online: <https://doi.org/10.3931/e-rara-55399>. Sections for which a faster tempo is suggested are marked in red.↩︎

Appendix 3

Giovanni Bassano, ‘Pulchra es amica mea’ (after Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina), from Mottetti, madrigali, et canzone francese (Venice, 1591; original print lost, see Friedrich Chrysander’s copy from 1890 in: D-Hs Ms. M B/2488), no. 51. Sections for which a faster tempo is suggested are marked in red.↩︎

Appendix 4a

Claudio Merulo, L’Olica (keyboard reduction), from Canzon di diversi per sonar con ogni sorte di stromenti (Venice, 1588) (RISM 158831), fols. A2r (Canto), E2r (Alto), C2r (Tenore), G2r (Basso).↩︎

Appendix 4b

Claudio Merulo, La Radivila, from Libro secondo di canzoni d’intavolatura d’organo (Venice: Angelo Gardano, 1606), fols. 6r–7v. Sections for which a faster tempo is suggested are marked in red.↩︎

Endnotes

Bibliography

John Bass, ‘Would Caccini Approve? A Closer Look at Egerton 2971 and Florid Monody’, in: EM 36 (2008), 81–93

Giovanni Bassano, Mottetti, madrigali, et canzone francese (Venice, 1591); original print lost, see Friedrich Chrysander’s copy from 1890 in: D-Hs Ms. M B/2488

Severo Bonini, Affetti spirituali a dua voci (Venice: Bartolomeo Magni, 1615)

Giovanni Battista Bovicelli, Regole, passaggi di musica, madrigali et motetti passeggiati, ed. Gawain Glenton, trans. Oliver Webber (Frome, 2018)

William Byrd, My Ladye Nevells Booke, GB-BL MS Mus. 1591

William Byrd, Organ and Keyboard Works: Fantasias and Related Works, ed. Desmond Hunter (Kassel, 2019)

Seth Calvisius, Bicinia septuaginta ad sententias evangeliorum anniversorium (Leipzig: Jacob Apel, 1599)

Giovanthomaso Cimello, The Collected Secular Works, ed. Donna G. Cardamone and James Haar, RRMR 126 (Madison, WI, 2001)

Luigi Collarile, ‘Claudio Merulo nell’intavolatura tedesca di Torino: il problema delle fonti’, in: In organo pleno: Festschrift für Jean-Claude Zehnder zum 65. Geburtstag, ed. Luigi Collarile and Alexandra Nigito (Bern, 2007), 89–112

Thomas Crecquillon, Gioseffo Guami, and Claudio Merulo, Canzon di diversi per sonar con ogni sorte di stromenti (Venice: Giacomo Vincenti, 1588)

Girolamo Dalla Casa, Il vero modo di diminuir (Venice: Angelo Gardano, 1584), <http://www.bibliotecamusica.it/cmbm/scripts/gaspari/scheda.asp?id=2817>

Ruth DeFord, Tactus, Mensuration, and Rhythm in Renaissance Music (Cambridge, 2015)

Robert Dowland (ed.), A Musicall Banquet (London: John Benson and John Playford, 1610) (RISM 161020)

J. Cheryl Exum, Song of Songs: A Commentary, The Old Testament Library (Louisville, KY, 2005)

Francesco da Milano and Pietro Paolo Borrono, Intabulatura di lauto del divino Francesco da Milano, et dell’eccellente Pietro Paulo Borrono da Milano […] libro secondo (Venice: [Gerolamo Scotto], 1546) (RISM 154630), <https://s9.imslp.org/files/imglnks/usimg/8/81/IMSLP263476-PMLP427136-milano_intabolatura_de_lauto_2.pdf>

Girolamo Frescobaldi, Toccate e partite d’intavolatura di cimbalo (Rome: Nicolò Borboni, 1616)

Andrea Gabrieli, Ricercari […] libro secondo (Venice: Angelo Gardano, 1595), <http://doi.org/10.3931/e-rara-56111>

Andrea Gabrieli, Il terzo libro de ricercari (Venice: Angelo Gardano, 1596), <https://doi.org/10.3931/e-rara-55399>

Andrea Gabrieli, Sämtliche Werke für Tasteninstrumente, ed. Giuseppe Clericetti, 6 vols. (Vienna, 1997–99)

Luis Gásser, Luis Milán on Sixteenth-Century Performance Practice (Bloomington, 1996)

Giles Earle’s Songbook, GB-Lbl Add. 24655

Hanns Haiden, Musicale instrumentum reformatum ([Nuremberg, 1610]) (VD17 12:651984X), <https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:bvb:22-jh.mus.d.1-3>

Monika Holl, ‘“Der Musica Triumph” – Ein Bilddokument von 1607 zur Musikauffassung des Humanismus in Deutschland’, in: Imago musicae 3 (1986), 9–30

Edward Huws Jones, The Performance of English Song, 1610–1670, 2 vols. (New York, 1989)

Robert Floyd Judd, ‘The use of notational formats at the keyboard: A study of printed sources of keyboard music in Spain and Italy c. 1500–1700, selected manuscript sources including music by Claudio Merulo, and contemporary writings concerning notations’, 2 vols., PhD thesis, University of Oxford, 1989

Orlando di Lasso, Bicinia, sive cantiones suavissimae duarum vocum (Antwerp: Pierre Phalèse and Jean Bellère, 1590)

Orlando di Lasso, Bicinia, sive cantiones suavissimae duarum vocum (Antwerp: Pierre Phalèse, 1609)

Orlando di Lasso, Novae aliquot et ante hac non ita usitatae cantiones suavissimae (Munich: Adam Berg, 1577)

Lewis Lockwood, ‘Text and Music in Rore’s Madrigal “Anchor che col partire”’, in: Musical Humanism and its Legacy: Essays in Honor of Claude V. Palisca, ed. Nancy Kovaleff Baker and Barbara Russano Hanning (Stuyvesant, NY, 1992), 243–51

Luzzasco Luzzaschi, Madrigali […] per cantare et sonare (Rome: Simone Verovio, 1601), <https://lccn.loc.gov/2008561305>

Domen Marinčič, ‘“Now quickly, now again slowly”: Tempo modification in and around Praetorius’, in: De musica disserenda 15/1–2 (2019), 47–69

Ascanio Mayone, Primo libro di diversi capricci per sonare (Naples: Costantino Vitale, 1603)

Claudio Merulo, Libro secondo di canzoni d’intavolatura d’organo (Venice: Angelo Gardano e fratelli, 1606)

Claudio Merulo, Toccate d’intavolatura d’organo […] libro primo (Venice: Simone Verovio, 1598), <https://mdz-nbn-resolving.de/details:bsb00094272>

Claudio Merulo, Toccate d’intavolatura d’organo […] libro secondo (Rome: Simone Verovio, 1604), <https://mdz-nbn-resolving.de/details:bsb00094273>

Luis Milán, Libro de música de vihuela de mano intitulado El maestro (Valencia: Francisco Díaz Romano, 1536), <http://bdh-rd.bne.es/viewer.vm?id=0000022795>

Johann Nauwach, Libro primo di arie, passegiate à una voce (Dresden, 1623)

Claude V. Palisca, The Florentine Camerata: Documentary Studies and Translations (New Haven, 1989)

Michael Praetorius, Syntagma musicum II (Wolfenbüttel, 1619) (VD17 3:315037M)

Bartolomeo Ramos de Pareja, Musica practica (Bologna: Baltasar de Hyrberia, 1482)

Christopher Reynolds, ‘Alessandro Striggio’s Analysis of Cipriano de Rore’s “Ancor che col partire”’, in: Journal of the Alamire Foundation 9, no. 2 (2017), 197–218

Francesco Rognoni, Selva de varii passaggi (Milan: Filippo Lomazzo, 1620)

Riccardo Rognoni, Passaggi per potersi essercitare Nel Diminuire terminatamente con ogni sorte d’Instromenti (Venice: Giacomo Vincenti, 1592), <http://conquest.imslp.info/files/imglnks/usimg/7/75/IMSLP292311-PMLP474374-passaggi_etc_ricardo_ognoni_parte2.pdf>

Bernhold Schmid, ‘“Nec non Tyronibus quàm eius artis peritioribus summopere inservientes.” – Zur gedruckten Überlieferung von Lassos Bicinien’, in: Yearbook of the Alamire Foundation 6 (2008), 177–203

The Fitzwilliam Virginal Book, GB-Cfm, Mu. MS 168

Nicola Vicentino, L’antica musica ridotta alla moderna prattica (Rome: Antonio Barre, 1555), <https://mdz-nbn-resolving.de/details:bsb00103730>

Nicola Vicentino, Ancient Music Adapted to Modern Practice, trans. Maria Rika Maniates, ed. Claude V. Palisca, Music theory translation series (New Haven, 1996)

Lodovico Zacconi, Prattica di musica (Venice: Bartolomeo Carampello, 1592)

Gioseffo Zarlino, Le istitutioni harmoniche (Venice: Francesco de Franceschi, 1558), <https://digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc25960/>