Italian Keyboard Intavolatura and Scribal Habit

Ian Pritchard

How to cite

How to cite

Abstract

Abstract

The commonly-understood conception of Italian keyboard intavolatura as a species of tablature notation carries with it certain implications: that intavolatura shares a basic affinity with lute and figure-based keyboard notational systems; that it is a ‘finger notation’, designed to transmit information necessary for the mechanical actions of playing, but not for voice leading and polyphonic detail; that its functioning was predicated upon a particular set of notational conventions or laws. The identification of intavolatura as a distinct notational system has been primarily established through a reading of Diruta’s treatise Il Transilvano – our most complete historical source describing intavolatura and the process of intabulating music in it – and through the volumes of keyboard music printed by 16th-century houses such as Gardano, Vincenti, and Verovio. However, not fully examined to this point has been conceptualizations of intavolatura on the part of scribes working on the Italian peninsula, mainly because there hasn’t been a thorough examination of extant intabulations in manuscript.

An examination of these intabulations further supports the conceptual framing of intavolatura as a system of conventions – a system that was tacitly understood by scribes as well as printing houses. An investigation into scribal habits further highlights the functioning of intavolatura as a kind of lute tablature for keyboard that used mensural notation in place of figures. At the same time, the use of mensural notation allowed for instances in which scribes use intavolatura as a kind of ‘partitura’, ignoring its conventions and rules in order to show the original voice leading of the polyphonic model. In their very divergence from intavolatura convention these instances further solidify the systematic conception of intavolatura; at the same time, they also show that scribes were aware of the possibility of bypassing the rules for the sake of showing polyphonic detail.

About the Author

About the Author

Ian Pritchard, harpsichordist, organist, and musicologist, is a specialist in early music and historical keyboard practices. A Fulbright scholar, he earned his PhD in musicology from the University of Southern California; his research interests include keyboard music of the late Renaissance and early Baroque, improvisation, notation, compositional process, and performance practice. Ian has released two discs of solo keyboard music, and has worked as a continuo player with many leading ensembles in Europe and the United States. Ian is currently based in Los Angeles, where he serves as Chair of Music History and Literature at the Colburn School Conservatory of Music. He also serves as music director of the Los Angeles-based ensemble Tesserae. In 2015 he was elected an Associate of the Royal Academy of Music.

Dedicated to the memory of Liuwe Tamminga (1953–2021)

Due to the fact that the notational signs used in Italian keyboard intavolatura are derived from mensural notation, the functional ‘identity’ of intavolatura as a species of tablature is grounded in notational convention – that is, the ways in which the notation ‘behaves’ on the page – rather than through the use of specific figures or signs, such as numbers or letters. The original users of intavolatura seemed to largely agree on the use of these conventions (we might call them ‘rules’),1 which diverge considerably in some ways from those of modern keyboard notation.2 In fact, the conventions align intavolatura with other figure-based tablature systems used in the Renaissance; as in these other tablatures, the notation in intavolatura was conceived on a mechanical basis, in that it prescribes the mechanical actions of the player on the keyboard rather than providing an abstract view of polyphonic structures and voice leading and the like.

While intavolatura and its distinctive conventions have been established in modern scholarship, the main emphasis of this scholarship has been on printed sources.3 Interestingly enough, an examination of extant intabulations in manuscript sources reveals a broad adherence to the same conventions; this would indicate a common understanding of intavolatura as a codified and commonly-understood system, one shared between its users – composer, players, scribes, printing houses – who in turn shared the basic thought processes and procedures that informed the system. At the same time, intabulations in manuscript suggest a greater tendency to depart from the conventions; however, these departures most typically take the form of brief instances within intabulations that otherwise follow them. In fact, these brief flashes of departure only serve to highlight the common adherence to intavolatura’s conventions; the rules of intavolatura work as a sort of background force, one that works through the scribe on a seemingly unconscious or semiconscious basis, whereas the departures seem to deliberately push against that force in a conscious manner.

Many of the instances of rule-breaking seem to be undertaken to reveal the voice leading of the model, deliberately going against the normal functioning of intavolatura in obscuring polyphony and voice leading through the action of its conventions. In other words, the intabulators ‘bend the rules’ in order to treat intavolatura like a partitura, or full score. In doing so these manuscript intabulations offer the modern reader a unique view on the processes and inner workings of intavolatura, including the intabulation process itself.

***

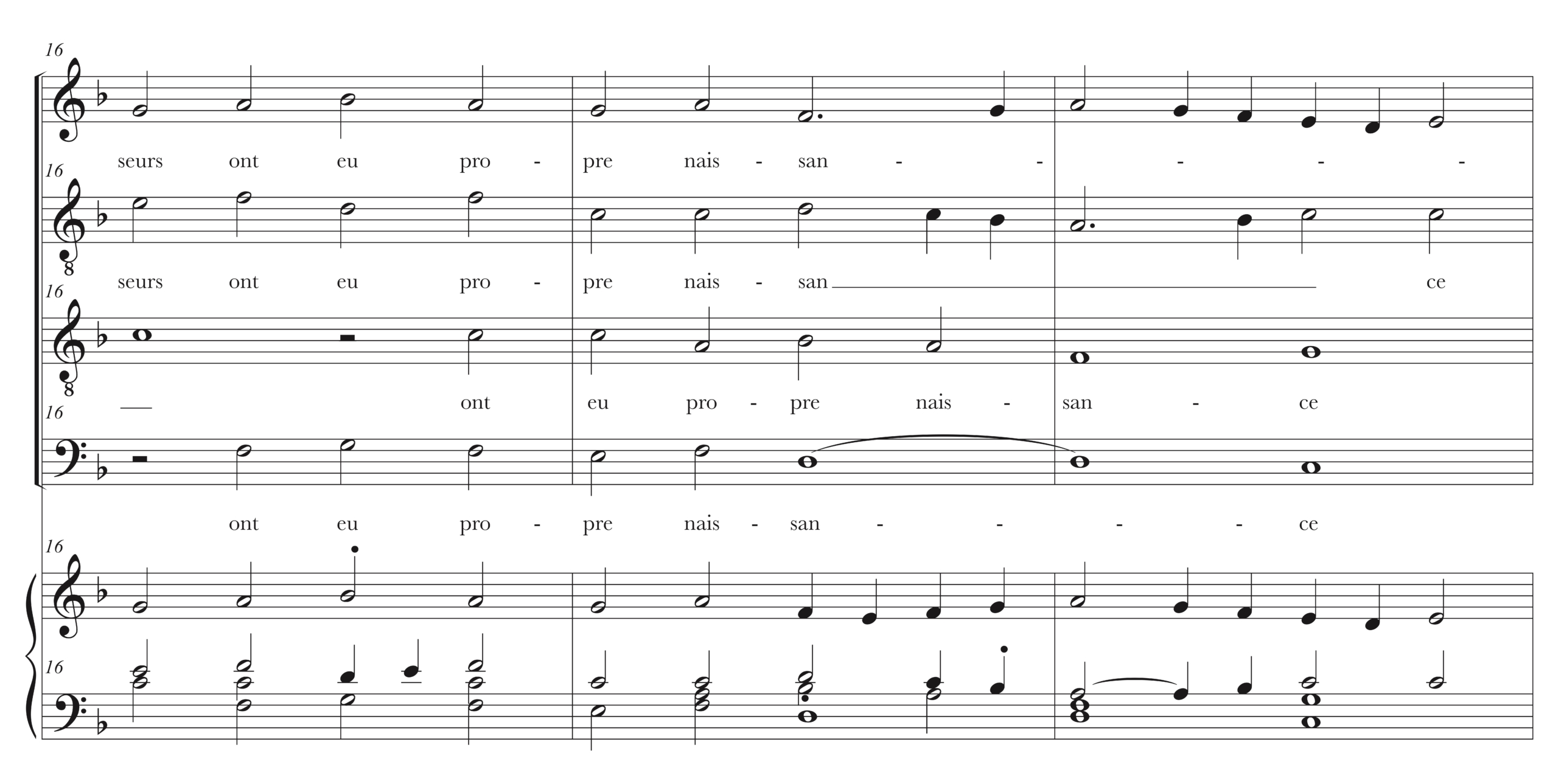

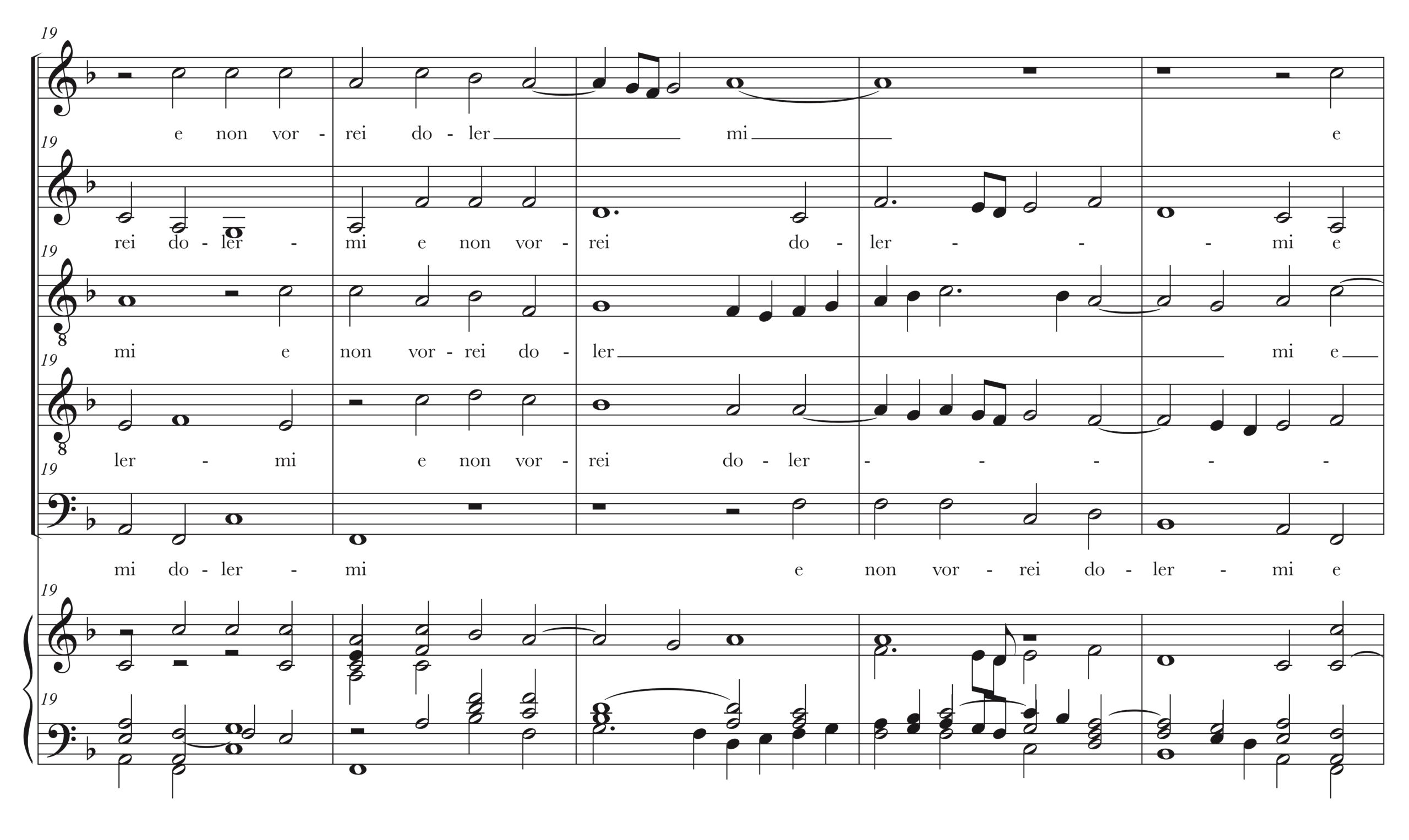

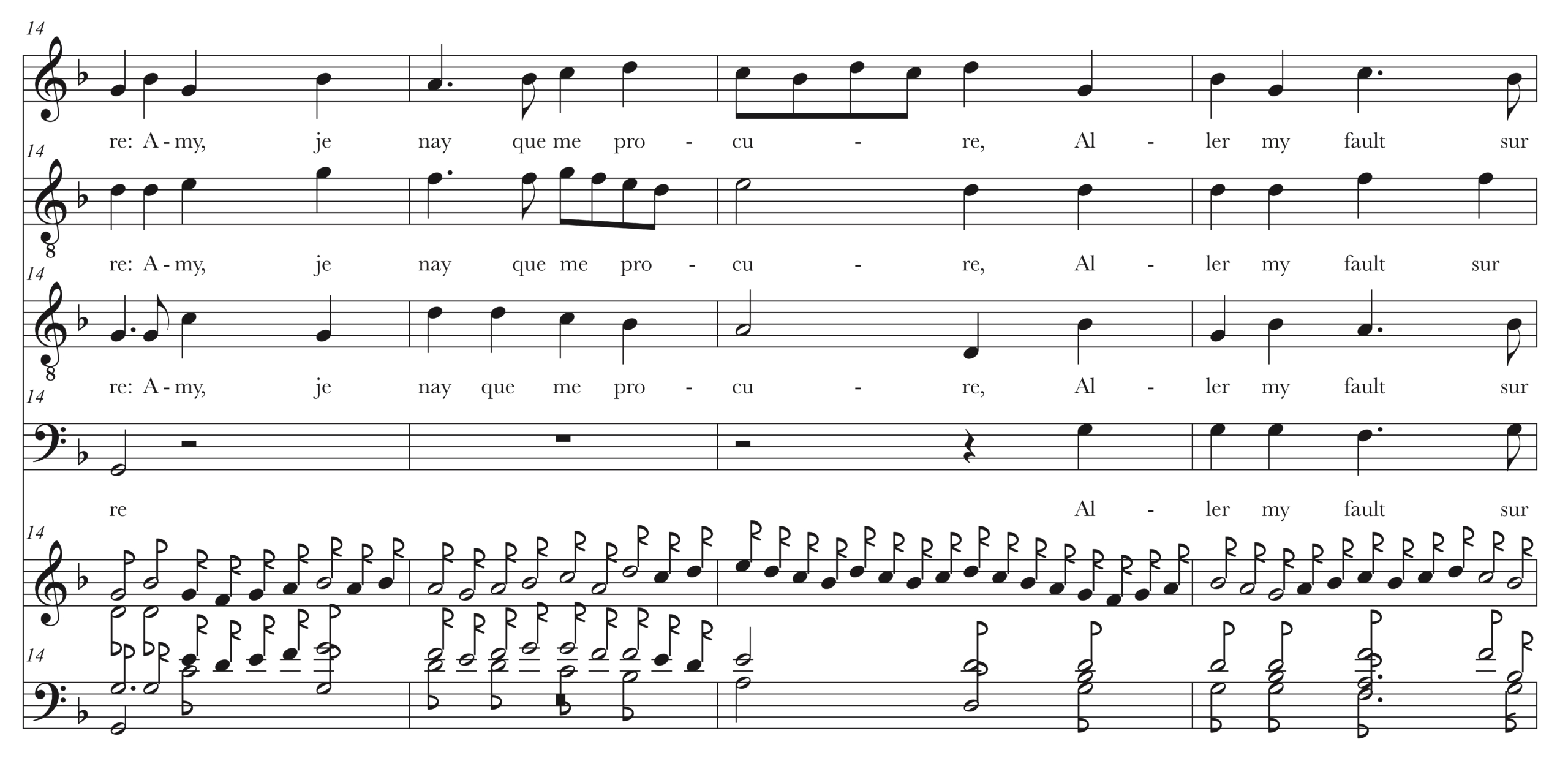

The notational conventions that define intavolatura are observable in the majority of works notated in the format, but their exact functioning is most easily observable in intabulations of polyphony, as a comparison of an intabulation with its polyphonic model allows for an in-depth examination of the parallel processes of adaption, (re)composition, and notational convention.4 In general, the majority of extant intabulations follow them. Here is a rather typical example from the Bardini Codex, an anonymous intabulation of Rore’s chanson ‘En voz adieux’ (Ex. 1). All of intavolatura’s conventions are more or less observable here.5

Ex. 1: A comparative model showing Rore’s chanson ‘En voz adieux’ (top four staves), alongside a transcription of the intabulation (anon.) from the Bardini Codex, mm. 16–23, fol. 89r–89v (I‑Fmba Ms. 967). The dots – which seemingly reinforce the key signature – are in the source.

To begin, the best-known feature of intavolatura is readily seen: the four parts of the original polyphony are arranged so that the notes to be played by the right hand are put in the top staff and the notes by the left in the bottom. As Augusta Campagne has convincingly demonstrated, the de facto arrangement for an intabulation in Italian keyboard intavolatura was for the top part to be placed on the top staff, and the bass and remaining middle parts (what Girolamo Diruta calls the parti di mezzo) in the left.7 We can see this clearly in mm. 16–18, with the bass and the middle parts all put on the bottom staff.

Other intavolatura conventions can be observed in this example as well: in m. 20, the alto voice is given an upward stem on the third beat, making it appear as if it belongs to the soprano voice that follows; in the fourth beat it moves to the bottom staff and appears in the tablature as if it belongs to the tenor. We see a similar thing in m. 16, in which the tenor c1 is restruck and given a downward stem; in the tablature this makes it look as if the bass and tenor form a continuous, single part. This practice represents another fundamental element, one that further defines intavolatura as a distinct notational system: the stem direction of a given note is dictated by its vertical placement in the score, rather than its role within one of the polyphonic parts. This results in ‘composite’ parts – formed of individual notes taken from, say, the tenor and the bass parts in the polyphony – created using the same process as a basso seguente part. When it happens in the upper voices, there is the parallel effect of a ‘soprano seguente’ part.8

The Rore intabulation contains other typical intavolatura conventions. The long notes in m. 19 and m. 21 (the soprano breve and bass semibreve in m. 19; the dotted alto d1 breve in m. 21) are split into shorter ones; in this case they are given ties although this could just easily not have been the case. In fact, from an understanding of performance conventions on plucked keyboard instruments during this time period, we know that ties might be broken in performance to avoid ‘leaving the [plucked keyboard] instrument empty’.9 In general, the practice of splitting longer notes into shorter ones – with ties or not – contributes to an inherent ‘verticalization’ of intavolatura, with polyphony reduced and made to coalesce around a structure of regular pulses (most typically at the minim level), an effect that has some parallels with the rhythmic system used in French and Italian lute intavolatura.10

Another typical convention is seen in the treatment of rests. In general rests in the polyphony are not notated when put into the tablature (‘to not entangle with or confuse the other notes’, as Diruta advises);11 this is seen here in m. 16. However, in m. 20 a rest that is not in the original is added. Often these added rests have a purely mechanical function: to simply inform the player to remove their finger from a key (we might call these mechanical rests, as they are literal instructions for a physical action). The added rest in m. 20, however, seems to be intended to clarify or signal the entrance of the tenor c1 – which, of course, is not the actual tenor of the model. This is what Alexander Silbiger called a ‘fictitious rest’.12 The intavolatura conventions work together to provide the appearance of voices that don’t exist in the model but work perfectly well and logically in the tablature; in other words, intavolatura notation presents a kind of score made up of the composite voices formed from the crossing of parts and the vertical placement of the individual notes. The functional existence of these composite voices is reinforced by the shared stem directions, which give the false impression of individual lines in a full score. In fact, all of intavolatura’s conventions work in concert to create this general effect. To expand upon Silbiger’s conception of ‘fictitious rests’, in a very real sense intavolatura has ‘fictitious voices’ or better, tablature voices (‘tablature’ in that they only exist in the tablature) that derive from yet supersede the original voices of the polyphony. In fact, they are conceptual and material recreations of the voices of the polyphony.13

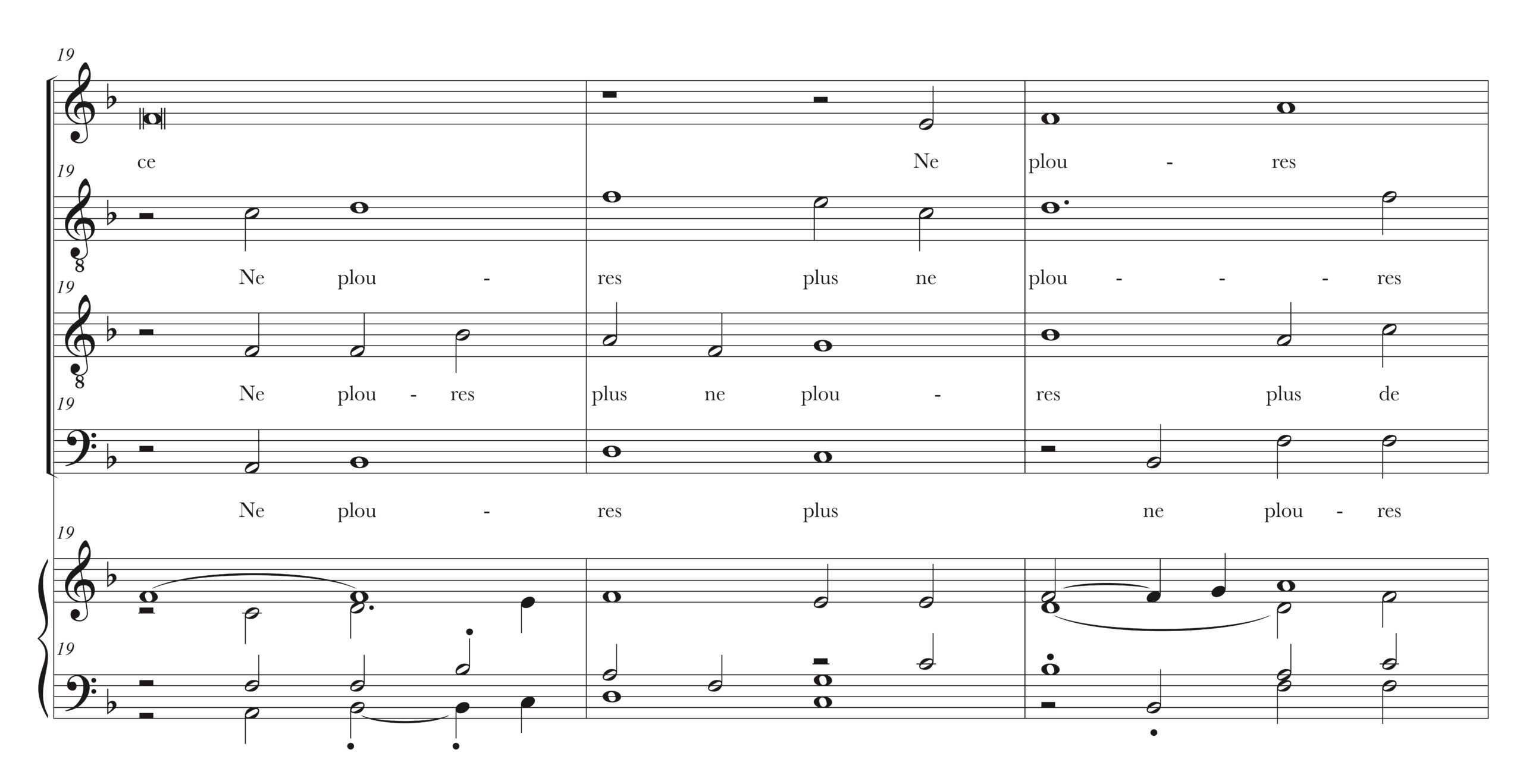

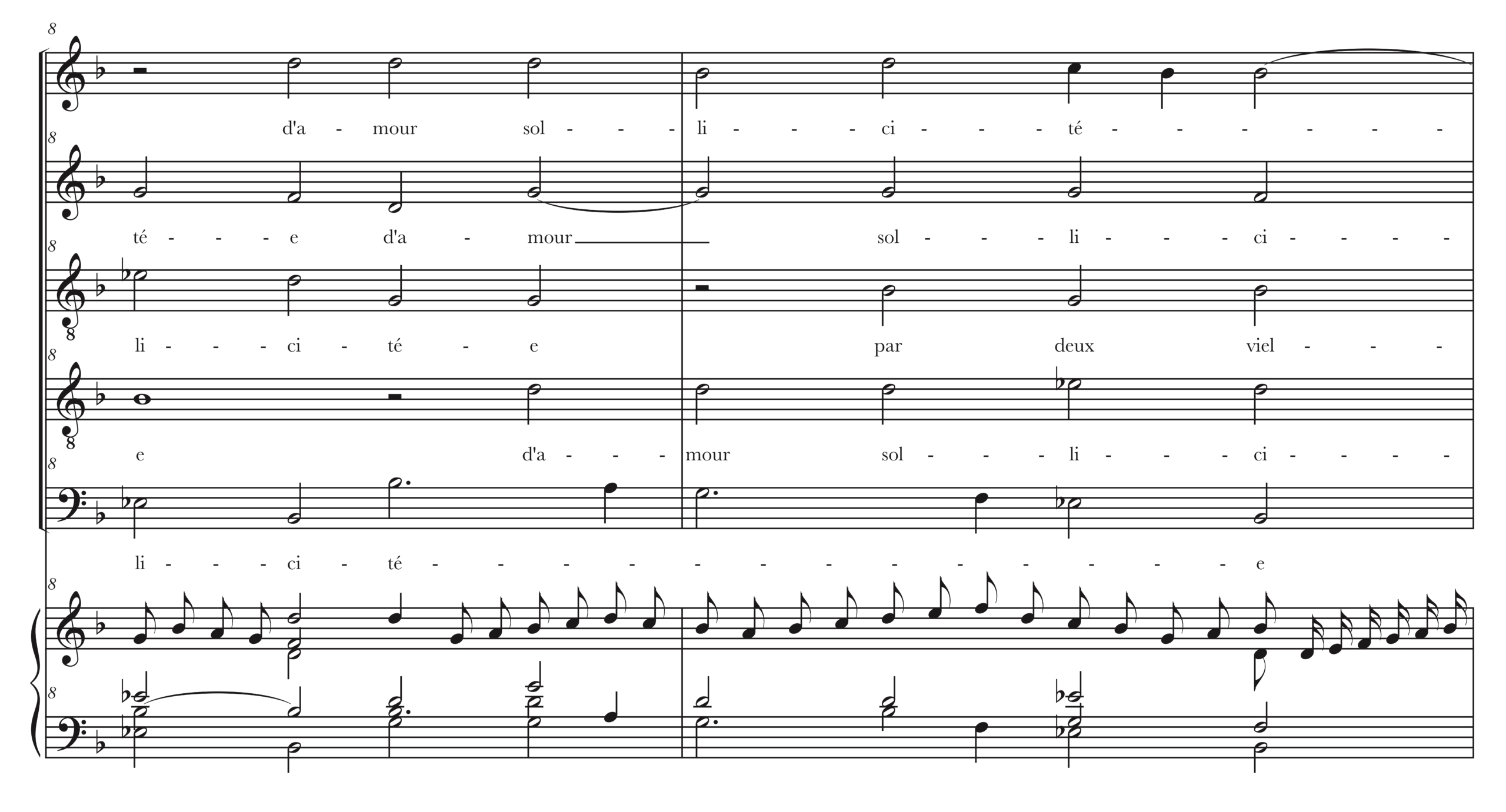

Tablature voices and the conventions of intavolatura also share a common link by virtue of being rooted in what we might identify as the idiom of 16th-century keyboard playing: the ‘unwritten traditions’ of keyboard playing in the cinquecento, which have to be seen as a broad set of musical activities that were largely grounded in improvisation but also included technical elements such as fingering, and composition.14 In Ex. 2, a fragment from an intabulation of Lasso’s ubiquitous ‘Susanne un jour’, we can clearly see the tendency of intavolatura to ‘translate’ vocal polyphony into idiomatic 16th-century keyboard textures.15

Ex. 2: Lasso’s ‘Susanne un jour’; bottom staves: transcription of the intabulation from the Layolle manuscript, mm. 25–30, fol. 21r–21v (I-Fl Ms. Acquisti e Doni 641).

As part of this process of translation, the complexity of the original polyphony is often reduced into textures that point towards a homophonic musical conception.16 Note, for example, the ‘blatant’ parallel fifths and octaves (mm. 25, 28), including the use of what we might call ‘filled octaves’ (after Galeazzo Sabbatini) in the left hand.17 Highlighting the closeness of this intabulation to idiomatic keyboard playing is the fact that the parallels are not a by-product of applying the normal intavolatura notational conventions to Lassus’ original polyphony, but are due to the recomposition of the polyphony by the intabulator: they are the product of the intabulator’s arranging, not Lassus.

The link with idiomatic keyboard music further highlights the fact that intavolatura’s conventions are interconnected, working in tandem to inform a system, a notational format that, for practical purposes, meets what we might call the standard ‘criteria’ for defining a tablature notation. As Alexander Silbiger succinctly put it:

One way of characterizing tablature notation is to say that it provides no information beyond what is required to realize a piece of music physically; or to put it less kindly: tablature addresses the fingers of the players rather than their musical understanding – their bodies rather than their minds.18

The conventions work together to create a notation that meets this ideal of ‘finger notation’; polyphonic detail is hidden by the action of the conventions, which seem obviously geared towards the practical expediencies of keyboard playing. Conceptually, it makes sense to view intavolatura as a close cousin of lute intavolatura, one that happened to use mensural signs as opposed to figures, lines, and flags. In this view, intavolatura remains, like lute intavolatura, an essentially graphical notation; the mensural notational signs are actually ‘figures’ that represent the literal action of depressing a key for a given length of time, rather than the more abstract representation of sounding tones. Such a view explains, for instance, the reasoning behind the bottom and top staves prescribing the disposition of parts between the left and right hands, and so forth.

At the same time, keyboard intavolatura cannot ‘construct’ its identity through the use of symbols like other tablature notations do; Italian lute tablature or German organ tablature are obviously removed from mensural notation because they don’t use its signs, and their direct relationship to performance is made clear by the graphical representation of the elements of performance, such as keys, frets, and strings. However, Italian keyboard tablature does not have the luxury of using graphical signs to unambiguously tell us that it is a tablature, geared towards playing rather than ‘musical understandings’. This leads to a certain level of ambiguity that is inherent to the system itself: it would be relatively easy for users of keyboard intavolatura to treat the two staves as a partitura, using stem directions of the notes to make clear which notes belong to which polyphonic voice, as opposed to obscuring the voice leading through the use of fictitious voice leading. As Silbiger demonstrated, this was the normal state of affairs not just in modern keyboard practice, but also in many historical systems that used two staves and mensural notation, from English Renaissance keyboard music to Bach fugues.19 Two-staff keyboard notation has a ready ability to adequately demonstrate complex voice leading, but intavolatura’s users normally ignored this possibility. In fact, the many instances in which they don’t ignore this possibility, bending intavolatura’s conventions to treat the notational like a partitura, only demonstrate the importance of the point.

***

It is obvious that establishing a global functioning for intavolatura – one that held for the vast majority of keyboard music written down in Italy in the 16th and 17th centuries – would entail that the majority of music notated in the format demonstrates a general adherence to the conventions described above. Luckily, a thorough examination of sources in intavolatura shows this to be the case. Even a quick scan through the Bardini Codex (from which Ex. 1 was taken) reveals a broad alignment with intavolatura and its functioning on the part of its scribe. In fact, while various sources may show different overall degrees of adherence, sources using intavolatura generally show a basic adoption of its conventions. This is especially the case when taking the role of individual scribal habit into account; it is very rare to find a single source, for example, that completely ignores all of the conventions of intavolatura. Rather, we see individual intabulations that show instances in which the ‘rules’ were not followed entirely: a scribe puts one too many notes in a staff or in a chord, creating a brief moment of a rather unidiomatic keyboard texture, or overcrowds the staff through the use of too many rests. In these instances, the system is still at play but its rules are bent a bit. In most cases, these examples stick out for being in an intabulation that otherwise does stick to the conventions, making them momentary instances of aberration rather than system-wide, defining features.

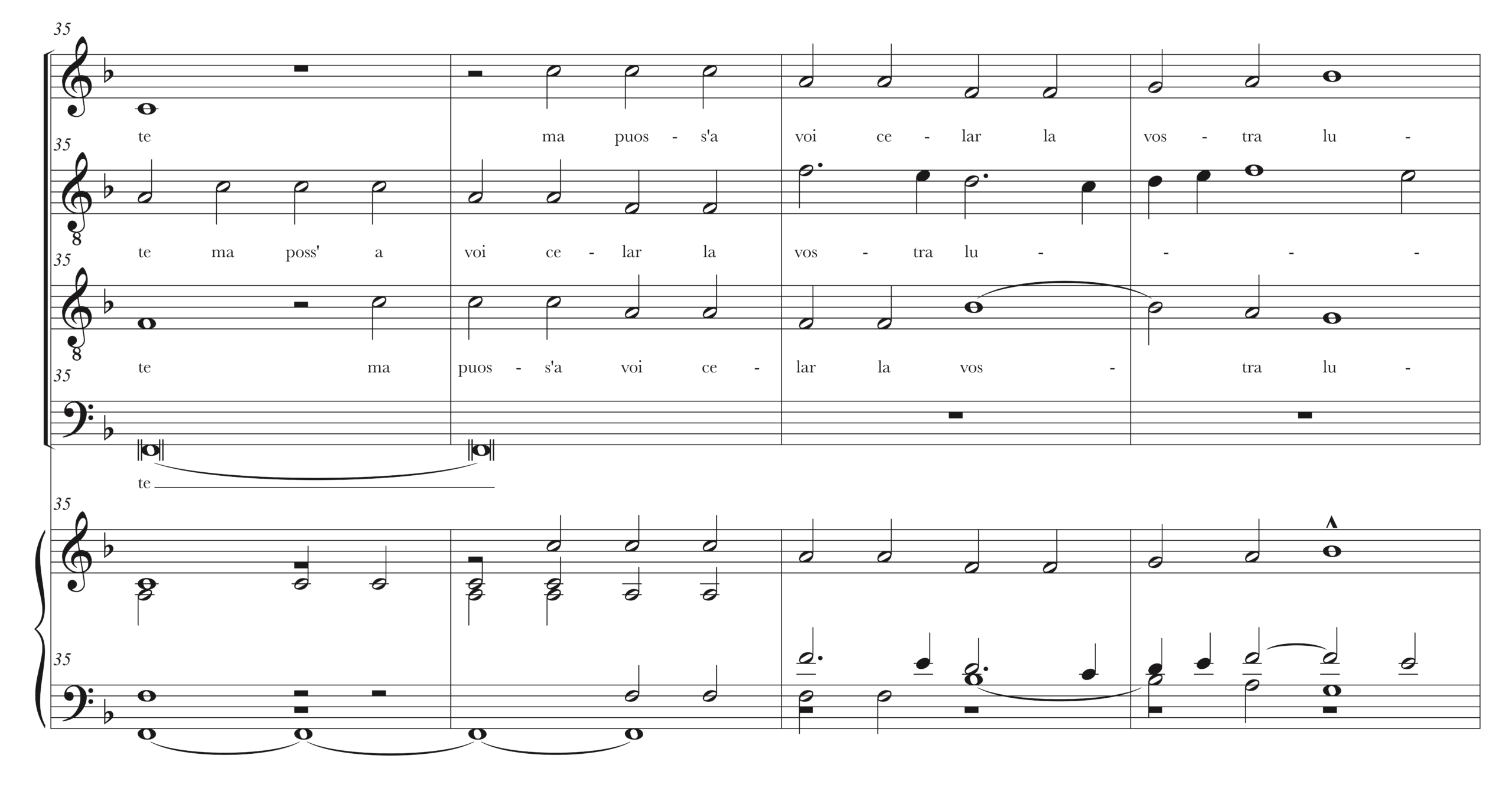

Each of the following examples (Exs. 3–5) is transcribed from a separate manuscript source, but in each we can observe a general adherence to intavolatura’s conventions, with a few deviations here and there. The first is from Ruffo’s madrigal ‘Per monti aplestri’, from the Pietro Francese manuscript (Ex. 3).

Ex. 3: Top staves: Ruffo’s ‘Per monti alpestri solitari et hermi’; bottom staves: transcription of the anonymous intabulation from the Pietro Francese manuscript, mm. 19–23, fol. 3r (D-Mbs Mus Ms. 9437).

Here, the intabulator’s apparent desire to faithfully transcribe the original polyphony leads to the inclusion of chord voicing that is decidedly unidiomatic, with awkwardly held tied notes in the middle of chords. At the same time, the conventions of intavolatura are followed broadly; see, for example, the seguente bass in mm. 20–21, and the treatment of the unison in the last measure of the example. In the second example, an anonymous intabulation of Maschera’s Canzona Quinta (‘La Maggia’) from the Castell’Arquato collection (Ex. 4), the inclusion of rests from the bass part in mm. 39–40 goes against intavolatura convention; usually these rests from the polyphony would not be notated. However, at the same time, stem direction rules are generally followed (for example, the treatment of the alto a1 and tenor f#1 in the top staff in m. 41), as is the staves-for-hands prescription (see the disposition of parts between the staves in the same measure).

Ex. 4: Top staves: Maschera’s Canzona Quinta La Maggia; bottom staves: transcription of the anonymous intabulation from the Castell’Arquato manuscripts, fasc. 10, mm. 38–41, fol. 8r–11r (I-CARcc).

The third example is taken from yet another anonymous intabulation, this one of Arcadelt’s ‘Occhi miei lassi ben’ (Ex. 5). This is also from Castell’Arquato, although, it should be noted, from a different scribe than the Maschera intabulation.20 Immediately notable are the several instances of ‘unnecessary’ rests; in normal intavolatura practice these rests would not be notated. In addition, there are several awkwardly large intervals that challenge the playability of the intabulation, as seen, for example, in m. 36. At the same time, however, a general adherence to intavolatura convention can again be seen; in, for example, the treatment of the unison d1 between the alto and tenor in m. 40.

Ex. 5: Top staves: Arcadelt’s ‘Occhi miei lassi ben’; bottoms staves: transcription of the anonymous intabulation from the Castell’Arquato manuscripts, fasc. 1, mm. 35–43, fol. 1v–2r (I-CARcc).

Therefore, while it is not uncommon to see exceptions to intavolatura convention, these exceptions are often contextualized within a general adherence to the conventions. In general, the old adage of the ‘exception to prove the rule’ seems to apply here. To think of it another way, intavolatura seems to be a constant background force in the minds of these intabulators, perhaps even operating on a subconscious or semi-subconscious level. In fact, the cognitive dissonance between a broad adherence to intavolatura conventions and the many instances in which the conventions are deviated from only highlights the mental ‘acceptance’, on the part of scribes and printers, of the systematic nature of intavolatura: its identity as a notational format as defined by a set of commonly-understood and intertwined set of conventions and unwritten rules.

***

Of course, if intavolatura operated as a distinct notational system with a commonly-understood set of conventions, one must ask why a scribe, publisher, or composer would ever depart from them. In the case of printed volumes, many instances of departure can at least partially be explained as the product of technological limitations. This has already been pointed out by scholars, and it is especially illuminated when comparing volumes produced using moveable type and volumes that were printed from copper plates; a classic example seen in the comparison between Merulo’s keyboard music printed using moveable type, such as the canzonas, and the toccatas, which were published by Verovio in Rome using intaglio techniques. The two volumes of toccatas demonstrate far more notational nuance and detail, while the canzonas show many instances in which one gets the sense that the notation was being pushed to its very limits.21

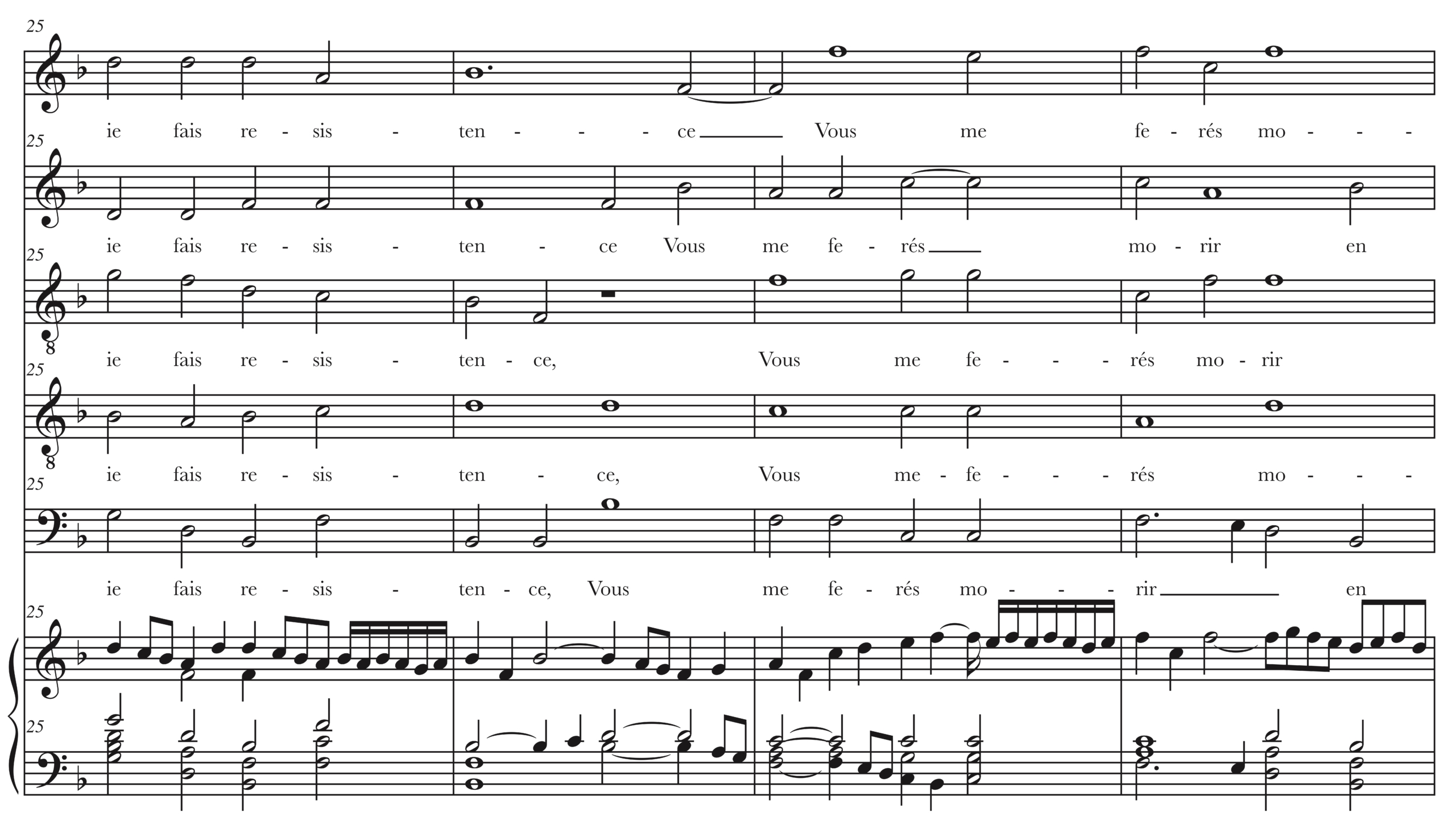

Ex. 6a: Top staves: Lasso, ‘Susanne un iour’; bottom staves: Andrea Gabrieli, ‘CANZON deta Susanne un iour A Cinque Voci d’Orlando Lasso’, mm. 8–9, [n.p.], in: Canzoni alla francese et ricercari ariosi, tabulate per sonar sopra istromenti da tasti […] libro quinto (Venice: Angelo Gardano, 1605).

In Ex. 6, two excerpts from Andrea Gabrieli’s intabulation of Lasso’s ‘Susanne un jour’ (which was printed in 1605 using moveable type), many instances can be observed in which Gabrieli (or someone in the Gardano firm, or perhaps Giovanni Gabrieli) goes against typical intavolatura convention in order to show Lasso’s original voice-leading.22 The tie in the left hand of m. 8 (Ex. 6a) is used to show that the two b-flat’s both belong to the quintus; without it, the stem directions – which do follow normal intavolatura procedure – would obscure this fact, leading one to believe that the notes had originally belonged to different voices. While long notes in intavolatura were typically split into shorter ones, as shown earlier, in this case the tie connects two notes that appear visually to be in different voices, at least in the tablature; if the tie were followed literally (and not broken in performance), it would also entail a rather awkward finger substitution. The dotted b-flat on the third beat – quite a finicky notational detail to include normally – does the same thing. The distribution of the chords in m. 42 (Ex. 6b) (including a stretch of a twelfth) is quite unidiomatic in terms of intavolatura convention and to the idiom and style of 16th-century Italian keyboard music.

Ex. 6b: Top staves: Lasso, ‘Susanne un iour’; bottom staves: Andrea Gabrieli, ‘CANZON deta Susanne un iour A Cinque Voci d’Orlando Lasso’, mm. 42–43, fol. 3r, in: Canzoni alla francese et ricercari ariosi, tabulate per sonar sopra istromenti da tasti […] libro quinto (Venice: Angelo Gardano, 1605).

It is also worth noting that including these details in the printing process must have cost additional labour and effort (this is perhaps especially noticeable when looking at the original source – see Fig. 1). For rather obvious reasons, it was much easier for a scribe (or a printing house using intaglio technique) to include this sort of notational detail, rather than a print shop using moveable type technology. The fact they are included, costs and labour notwithstanding, adds weight to the importance of their inclusion.

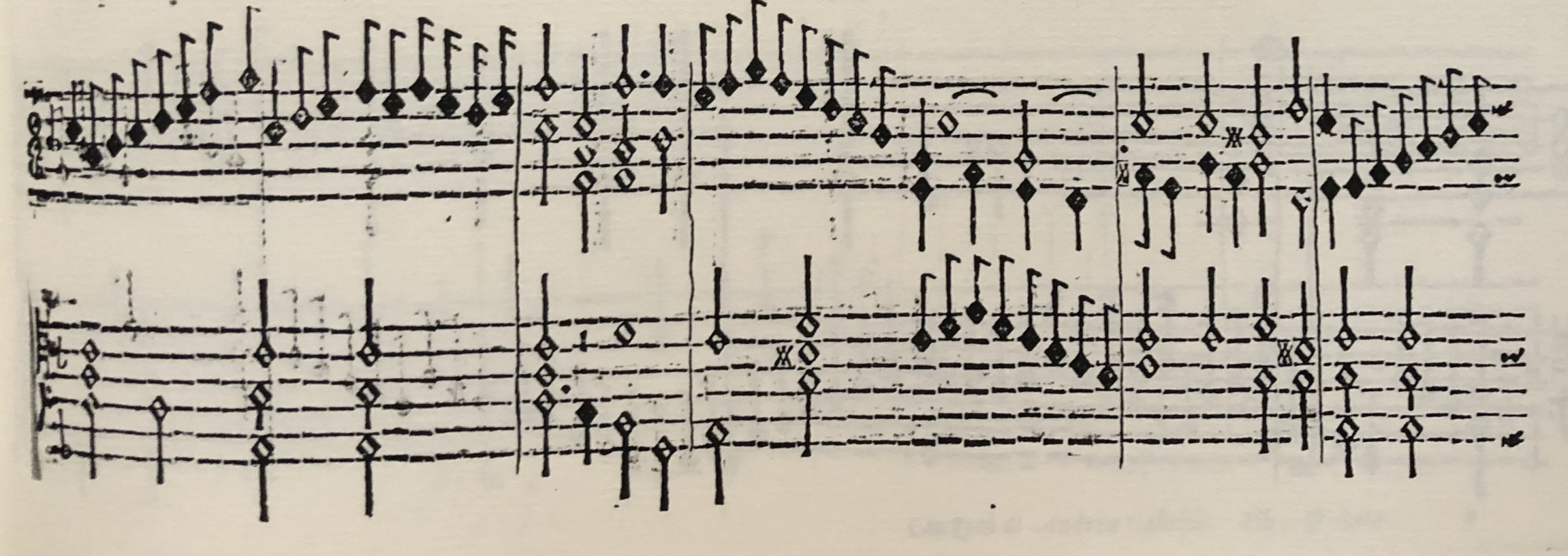

Fig. 1: Andrea Gabrieli, ‘CANZON deta Susanne un iour A Cinque Voci d’Orlando Lasso’, mm. 41–44, in: Canzoni alla francese et ricercari ariosi, tabulate per sonar sopra istromenti da tasti […] libro quinto (Venice: Angelo Gardano, 1605), 3r.

Having said that, instances such as the ones shown in Gabrieli’s intabulation are also fairly common in manuscript intabulations, indicating that print limitations are far from the only reason to explain instances in which intavolatura conventions were not followed. Highly intriguing are examples in which the rules of intavolatura – which generally work to hide polyphonic detail in favour of playability – are broken in order to reveal polyphonic voice leading.

It is notable that the vast majority of these ‘rule breaking’ episodes seem to be grounded in what appears to be an attempt, on the part of the scribe, to use the tablature as a partitura; in doing so, the scribe goes against the general ethos and aesthetic – and, of course, the conventions – of intavolatura. However, the possibilities of intavolatura being used as a partitura seemed apparent to many scribes, some going so far as to use special symbols or techniques to reveal voice-leading of the original polyphony, pushing against the ‘natural’ tendency of intavolatura to hide it. One of the two scribes of the Layolle manuscript consistently uses a custos or direct sign23 to signal instances in which voices move from stave to stave.24 These signs thus clarify the original polyphony of the model, pushing back against intavolatura’s conventions as they ‘blindly’ work to hide the original voice motion – this blind functioning is again cast into relief by the fact that the intabulation normally does follow the conventions. Interestingly enough, in other intabulations rests can be used for a similar purpose (the fictitious rest in the left hand of m. 42 seems to clearly be used to indicate the fact that tenor part moves from the bottom to the lower staff in Ex. 6a above), although here the signs are clearly visually distinct from rests.25

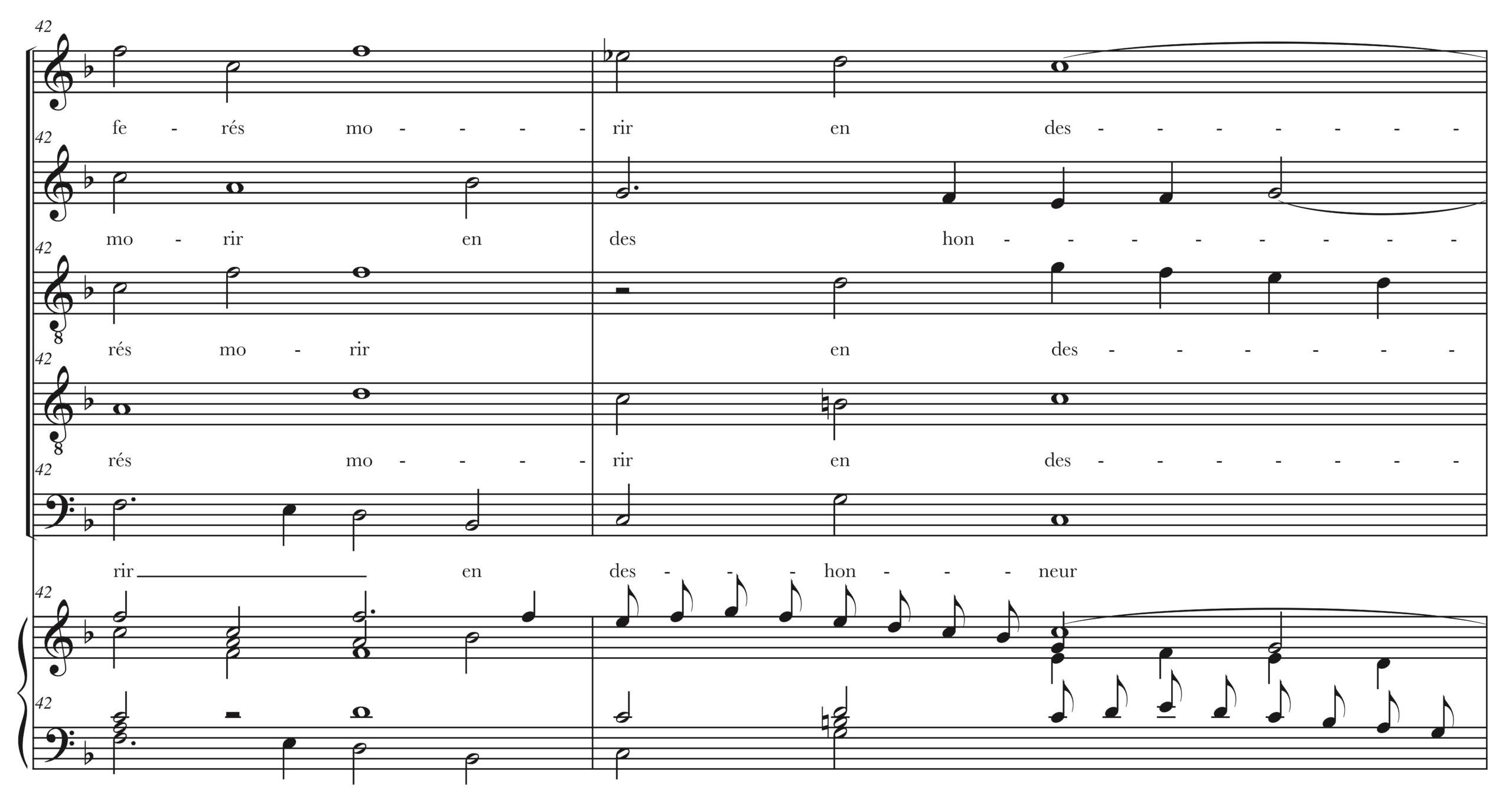

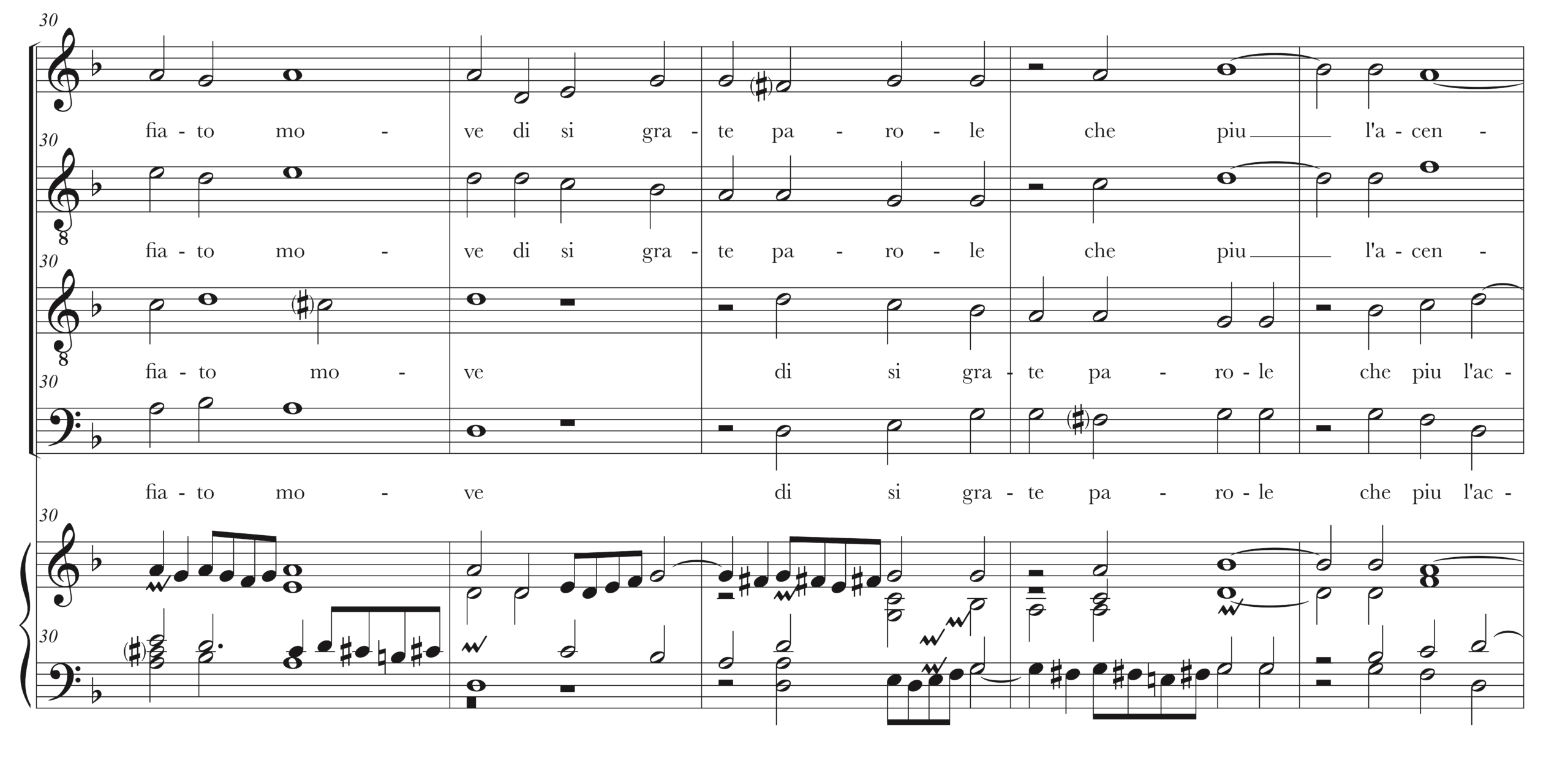

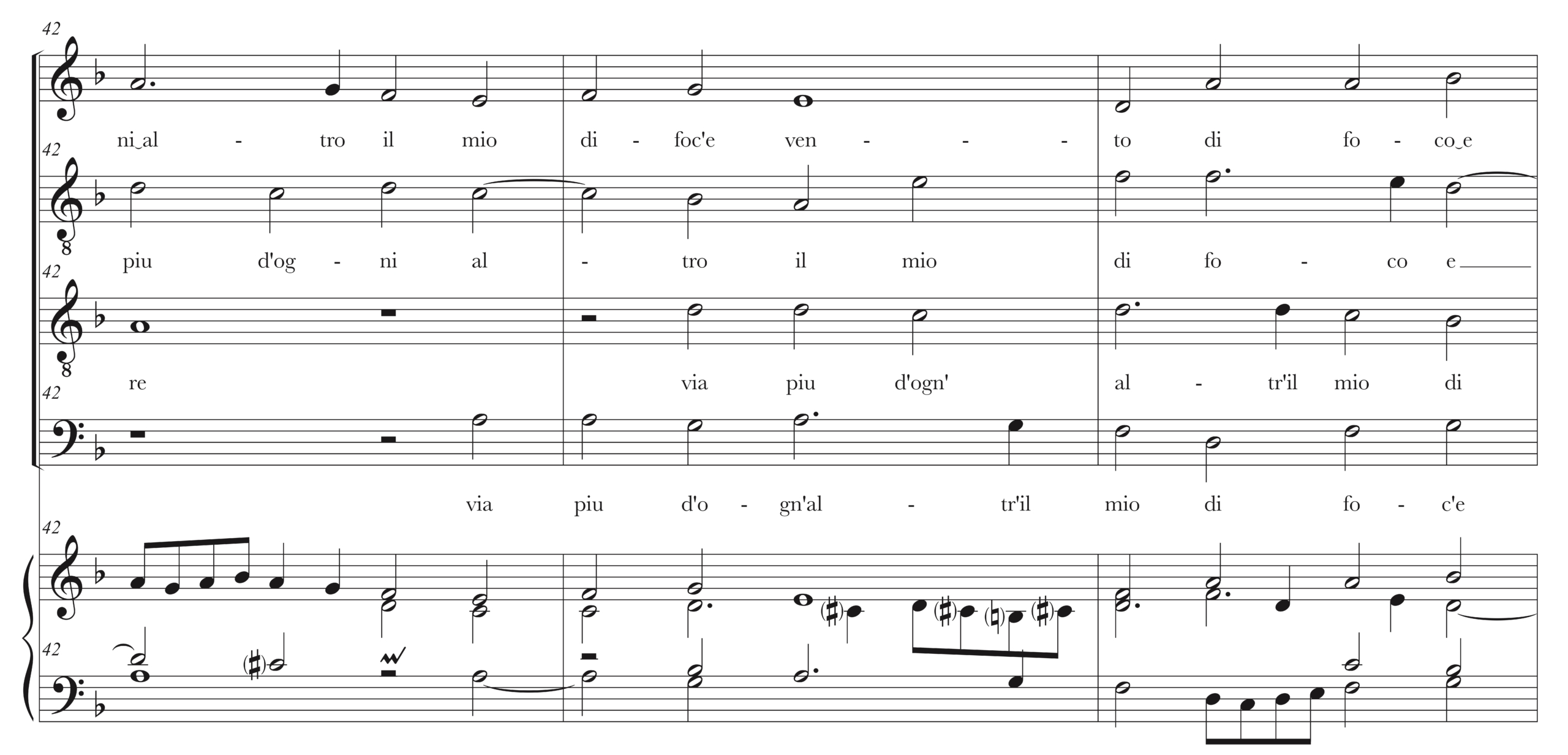

The intabulation of Berchem’s ‘O s’io potessi donna’ (Ex. 7) clearly demonstrates the functioning of these custos signs. In a sense, the scribe uses them to subvert the tendency of intavolatura to hide this sort of detail automatically. In m. 31, the sign is used to signal that the tenor moves to the right-hand staff on the downbeat, and is then used again for its return to the left-hand staff in m. 33. In m. 32, a slew of custos signs is used (four in total!), to signal swapping between the two parti di mezzo on the two staves. The tendency on the part of the scribe to prevent voice-leading from being hidden by intavolatura is further supported by the fact that they often combine the use of the custos signs with double stems, which are of course wholly unidiomatic to intavolatura and its normal ‘suppressing’ of double-stemmed notes. The double-stemmed notes are used, however, to show unisons that occur in the polyphonic model – see, for example, the double-stemmed g in the left-hand of m. 33 (Ex. 7a), or the double-stemming (in two voices) in m. 44 (Ex. 7b). Yet, at the same time we can still observe the background action of intavolatura conventions as a global force throughout the intabulation as a whole. In m. 34, the voice leading is obscured between the inner parts as the intabulator follows the general rules for stem directions; in addition, unisons are not treated uniformly: the unison between the alto and the tenor in m. 31 (Ex. 7a) is not given a double-stem, nor are the unisons in m. 43 (Ex. 7b) on the third and fourth beats. Note that the unison on the downbeat of m. 44 is double-stemmed, however. This might indicate that, again, intavolatura’s conventions were seen as an undeclared background force, one that was perhaps understood subconsciously by the intabulator – or perhaps consciously as they felt the need to ‘push against’ it.

Ex. 7a: Top staves: Berchem’s madrigal ‘O s’io potessi donna’; bottom staves: transcription of the intabulation from the Layolle manuscript (by Alamanne de Layolle?), mm. 30–34, fol. 4v (I-Fl Ms. Acquisti e Doni 641).

Ex. 7b: mm. 42–44, fol. 5r.

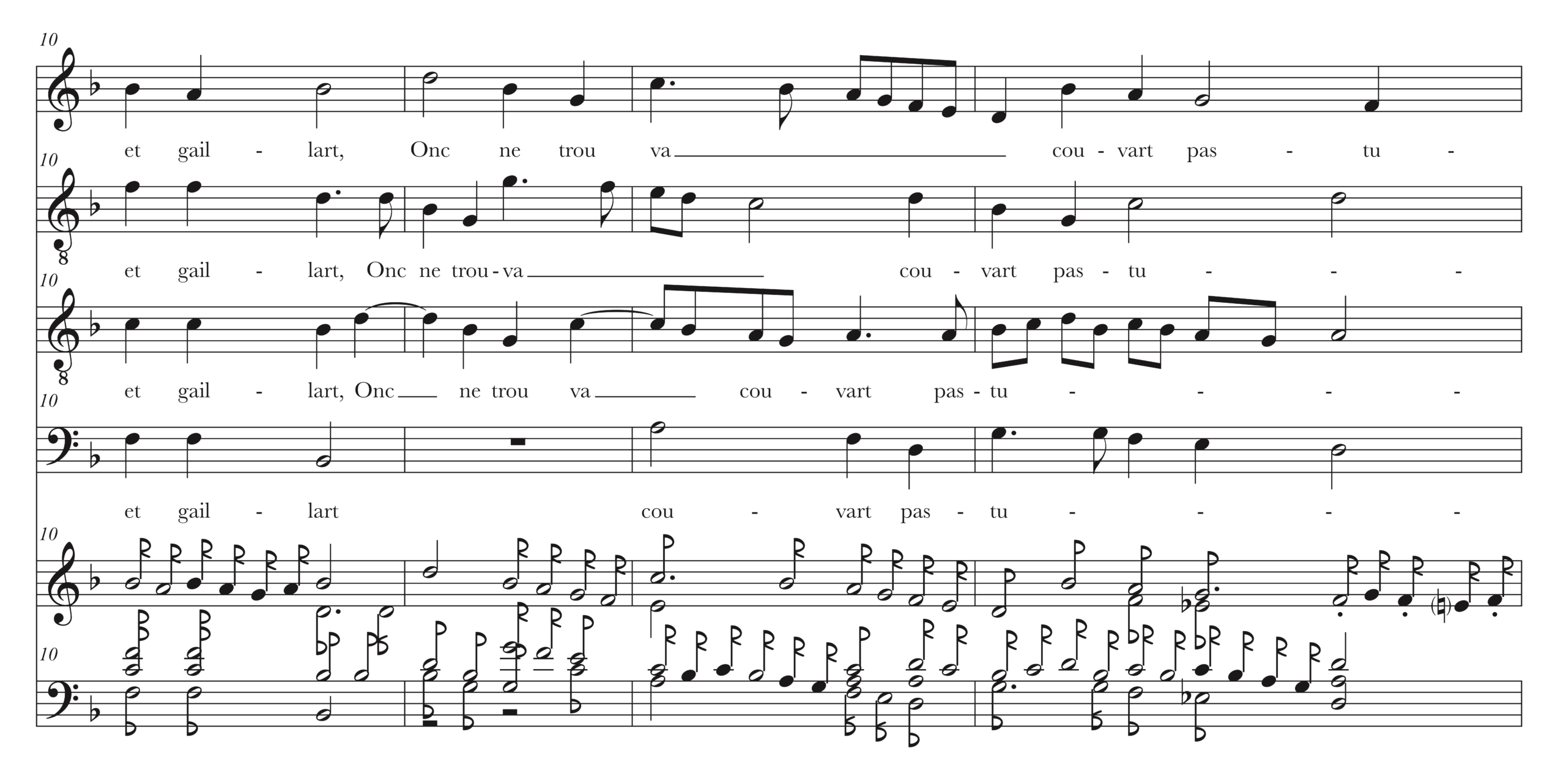

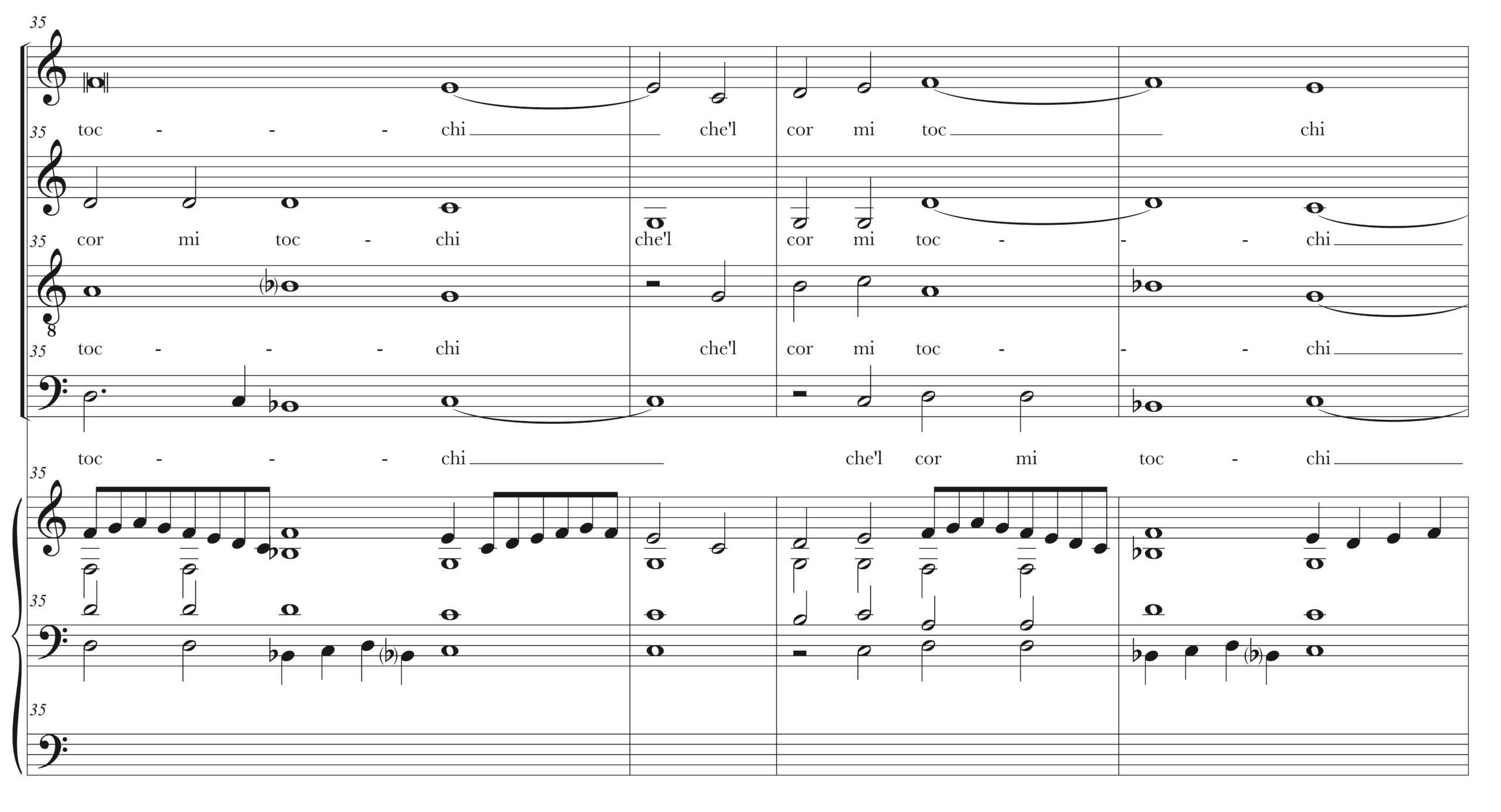

As a side note, many of the particular scribal habits seen in the intabulations in the Layolle manuscript – notably, especially those attributed to Alamanne de Layolle by Frank d’Accone – are also observable in the intabulations of Pierre Attaingnant (but not the use of the custos sign to show voice leading). In Ex. 8, from Attaingnant’s Vingt et cinque chansons musicales reduictes en la tabulature (1530), ‘unnecessary’ rests taken from the original polyphonic parts are seen in the bottom staves of mm. 11 and 15 (as shown above, this is not a typical feature of Italian intavolatura.)

Ex. 8: Top staves: Janequin’s ‘Aller my fault’; bottom staves: transcription of the intabulation from Attaingnant’s Vingt et cinque chansons musicales reduictes en la tablature (Paris: Attaingnant, 1530), fol. 41, mm. 10–17. In my transcription, notes have been transcribed into modern types, although details such as hand distribution, rest placement, and stem direction and length have been transcribed accurately.

At the same time, many of the conventions of Italian intavolatura can be observed – most importantly, the ‘staves for hands’ rule – although not all of them; for example, the adoption of stem direction based on the vertical placement of the note in the staff is not followed consistently (see note 2 above). Still, a broader examination of the connections between Attaingnant’s published intabulations and intavolatura – and, more broadly, the relationship between Attaingnant’s notation and intavolatura – is needed, especially as Daniel Heartz has pointed to hints of connection between French publishers and prominent early prints and print shops involved with intavolatura.26

***

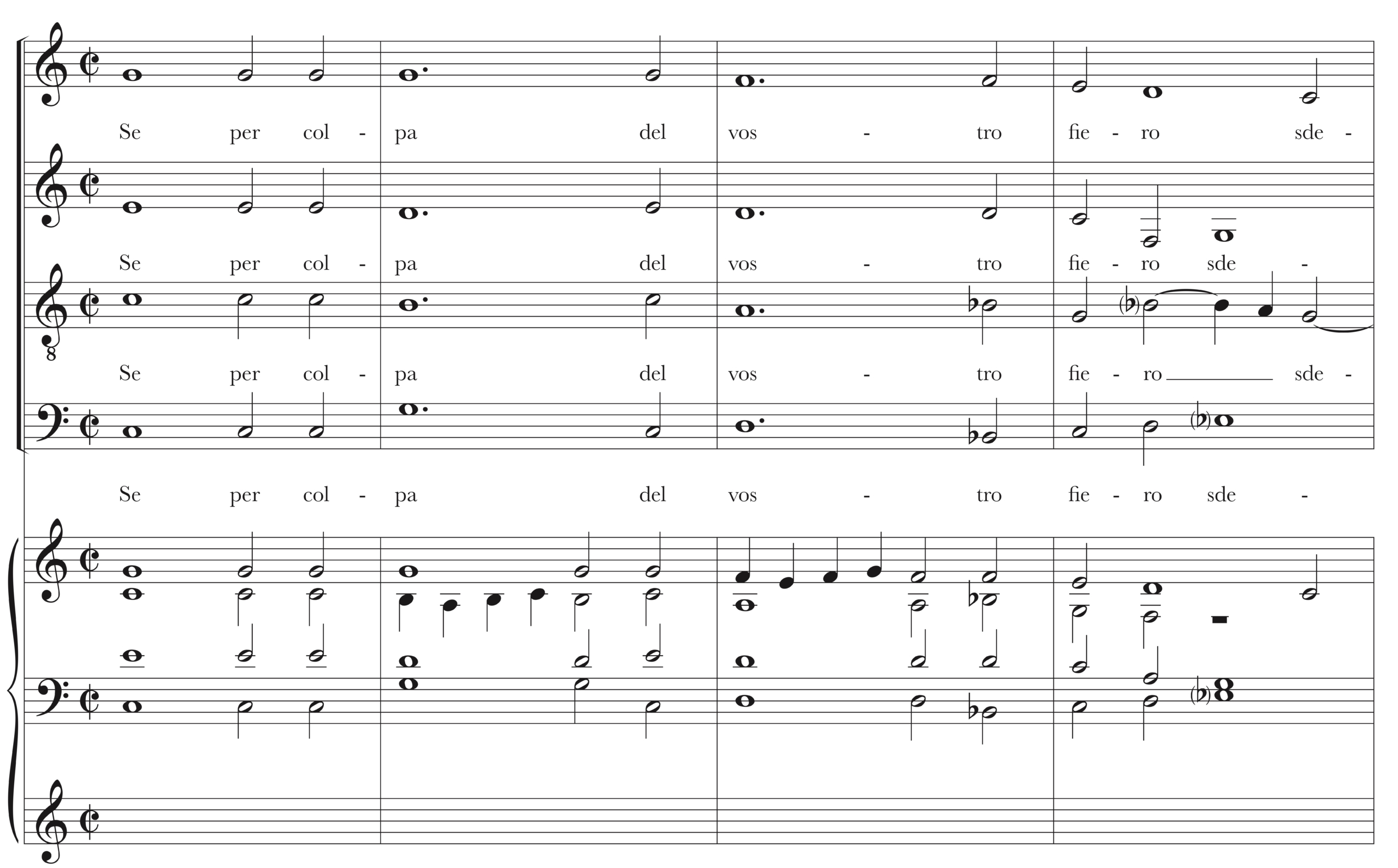

Broadly speaking, the discussion above highlights the utility of examining the intabulation process as a way to see the ‘inner-workings’ of intavolatura – and, perhaps, the inner working of the mind of the intabulator as well – in that this process clearly demonstrates awareness of both intavolatura as a system and the possibility of breaking its conventions. One instance – an anonymous intabulation of Arcadelt’s ‘Se per colpa’ from the Castell’Arquato collection – is arguably an ‘intabulational’ sketch and therefore offers a glimpse of the intabulation process itself; if this is the case, it would be one of the few examples we have of this that is specific to keyboard intavolatura.27 This intabulation likewise shows an attempt to use intavolatura as a partitura, while also revealing an awareness of the basic functioning of intavolatura’s rules and conventions.

Ex. 9a: Top staves: Arcadelt’s ‘Se per colpa’; bottom staves: transcription of the intabulation from the Castell’Arquato manuscripts, fasc. 5, mm. 1–8, fol. 22v.

The sketch is in three staves as opposed to the normal two; this is similar to the notation of many of the keyboard works attributed to Veggio in the collection, and is in fact a tendency common to one particular scribe. At first glance, the intabulation appears to be an attempt to write a complete partitura rather than a tablature. The normal intavolatura rule of stem directions is not followed at all; instead stems are used to clarify the contour of the original voices. Perhaps somewhat ironically, this lends further credence to the existence of ‘tablature voices’: that is, the notion that series of notes with the same stem direction in a tablature can be interpreted as constituting a new tablature part. However, at the same time this intabulation clearly seems meant to work as an idiomatic keyboard adaption: note the adaption of the polyphony into a more squarely chordal texture with the restriking of chords (m. 2 and 3, Ex. 9a), the addition of parts (m. 6, Ex. 9a), and even the extension and restriking of chords into rests (m. 8, Ex. 9a). Stereotypical keyboard ornamental figures are added, and the polyphony is briefly rearranged to accommodate them. This rearrangement of the original voice leading is also used to facilitate a more generally idiomatic texture, one that is more normally seen in intabulations.

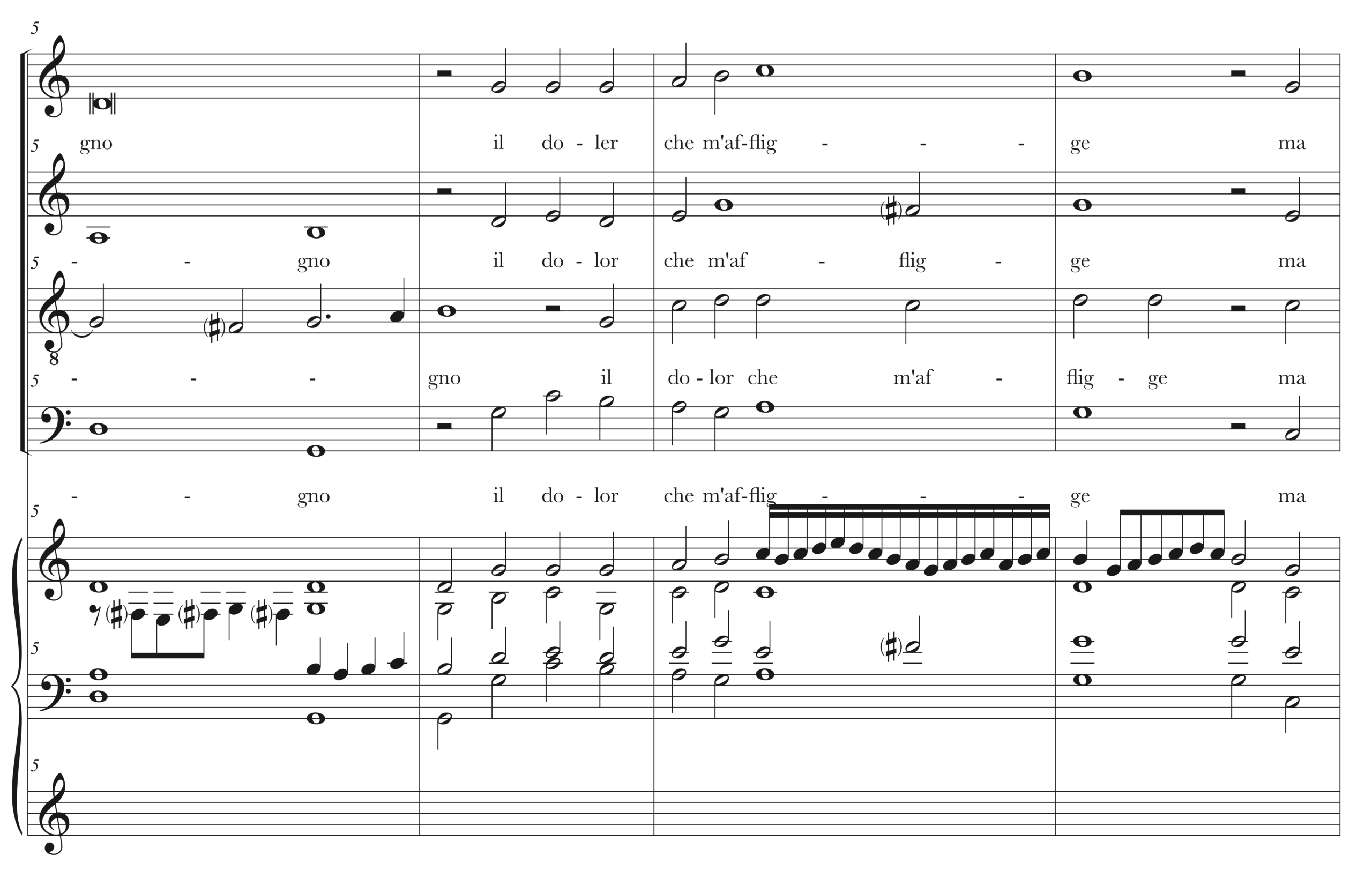

Ex. 9b: mm. 35–38, fol. 23r.

In addition, there are fascinating instances in which the parti di mezzo briefly swap places. These usually only last for a few beats, and seem to be a continuation of the ‘keyboardistic’ logic in the transcription (and a kind of preparation for the creation of proper tablature parts?), and/or to facilitate the inclusion of diminutions in another part. For example, in m. 37 (Ex. 9b) the tenor part of the vocal original – which is usually placed in the right hand in the intabulation – briefly migrates to the left hand. Is this to facilitate the upcoming passaggio (also in m. 37) in the soprano? It also makes sense to allow the ‘tablature alto’ (that is, the implied lower voice in the right-hand staff) to continue its logical journey that begins on the g in m. 35, instead of swapping back up to the b as the polyphonic tenor continues in m. 37. In fact, it could be argued that the logical continuation of the c1 in the intabulation from mm. 35 to 36 kicks off the whole swapping of parts in the first place; note that this also includes a brief rearrangement of the polyphony in m. 36, with the addition of the c1 in the left hand of the tablature and the absorption of the tenor’s rest and g into the long g of the polyphonic alto part. This sort of rearrangement (or recomposition) is commonly observed in intabulations. It is also interesting that the chords formed in places such as the last beats of mm. 35 and 38 are the typical ‘filled octave’ chords – an octave with a fifth in the left hand – so commonly seen in cinquecento keyboard style. The brief instance of recomposition in m. 36 – in which the filled-octave chord in m. 35 is extended in favour of Arcadelt’s original polyphony – highlights the point.

In general, this intabulation appears to be a hybrid intavolatura-partitura. I wonder if it might be an example of a ‘prep score’ for what might have eventually become a more run-of-the-mill type of intabulation, or in other words a version of the score that Diruta advises beginners to make from part-books before intabulating.28 The use of three staves might facilitate the process overall. If so, this might once again indicate an awareness of intavolatura as a background force: I think we could even ask ourselves if intabulators were even consciously aware of the system they may have been attempting to ‘hack’ when breaking the rules of intabulation.

***

As recent scholarship has demonstrated, intabulations and tablature notations are long overdue for a more thorough examination. In the present case, even a brief examination like the one conducted in this article shows that they can reveal quite a lot about the musical thought processes and conceptions of keyboardists in the Renaissance. These would include not only abstract musical conceptions and musical practices, but also the way in which these conceptions and practices were translated into a functioning notational system. Therefore, on a broader level, one could argue that a thorough examination of intabulations is absolutely essential to any study of improvisation and composition in Renaissance culture.

Endnotes

Bibliography

Andrea Antico, Frottole intabulate per sonare organi, libro primo (Rome: Andrea Antico, 1517), facsimile ed. (Bologna, 1970)

Pierre Attaingnant, Vingt et cinque chansons musicales reduictes en la tablature (Paris: Attaingnant, 1530), <https://mdz-nbn-resolving.de/details:bsb00082256>

Pierre Attaingnant, Transcriptions of Chansons for Keyboard, ed. Albert Seay, CMM 20 (n.p.: AIM, 1961)

Paul Anthony Luke Boncella, ‘The Classical Venetian Organ Toccata (1591–1604): An Ecclesiastical Genre Shaped by Printing Technologies and Editorial Policies’, PhD thesis, Rutgers University, 1991

David Bryant, ‘Gabrieli, Giovanni’, in: Grove Music Online, <https://doi.org/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.40693>

Hans Buchner, Sämtliche Orgelwerke, ed. Jost Harro Schmidt, 2 vols., EdM 54/55 (Frankfurt am Main, 1974)

Augusta Campagne, Simone Verovio: Music Printing, Intabulations and Basso Continuo in Rome around 1600, Wiener Veröffentlichungen zur Musikgeschichte 13 (Vienna, 2018), <https://www.vr-elibrary.de/doi/pdf/10.7767/9783205207184>

Augusta Campagne and Elam Rotem, Keyboard Accompaniment in Italy around 1600: Intabulations, Scores and Basso Continuo (Basel: Schola Cantorum Basiliensis, 2022), <https://forschung.schola-cantorum-basiliensis.ch/dam/jcr:4c34cff1-be77-4a28-a71b-83a3fced72ae/Keyboard Accompaniment Italy 1600.pdf>

Marco Antonio Cavazzoni, Recerchari, motetti, canzoni […] libro primo (Venice: Bernardo Vercelensis, 1523)

Leon Chisholm, ‘Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony, Circa 1600’, PhD thesis, University of California, Berkeley, 2015, <https://escholarship.org/uc/item/950881g4>

Giuseppe Clericetti, ‘Criteri per un’edizione moderna della musica per strumenti a tastiera di Andrea Gabrieli’, in: Andrea Gabrieli e il suo tempo, ed. Francesco Degrada, Studi di musica veneta 11 (Florence, 1987), 353–86

Victor Coelho and Keith Polk, Instrumentalists and Renaissance Culture, 1420–1600: Players of Function and Fantasy (Cambridge, 2016)

Frank D’Accone, ‘The ‘Intavolatura di M. Alamanno Aiolli’: A Newly Discovered Source of Florentine Renaissance Keyboard Music’, in: MD 20 (1966), 151–74

Frank D’Accone, ‘Layolle, Francesco de’, in: Grove Music Online, <https://doi.org/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.16159>

Girolamo Diruta, Seconda parte del Transilvano (Venice: Giacomo Vincenti, 1609), <http://www.bibliotecamusica.it/cmbm/viewschedatwbca.asp?path=/cmbm/images/ripro/gaspari/_D/D019/>

Dinko Fabris, ‘Lute Tablature Instructions in Italy: A Survey of the Regole from 1507 to 1759’, in: Performance on Lute, Guitar, and Vihuela: Historical Practice and Modern Interpretation, ed. Victor Anand Coelho (Cambridge, 1997), 16–46; repr. in: Musical Theory in the Renaissance: A Library of Essays on Renaissance Music, ed. Christle Collins Judd (Burlington VT, 2013), 451–82

Andrea Gabrieli, Canzoni alla francese et ricercari ariosi, tabulate per sonar sopra istromenti da tasti […] libro quinto (Venice: Angelo Gardano, 1605)

Angelo Gardano, Musica de diversi autori (Venice: Angelo Gardano, 1577) (RISM 157711), facsimile ed. (Bologna, 1971)

John Griffiths, ‘Turning the Tables: Reassessing Tablature’ (presentation, 2021 Annual Conference of the Musicological Society of Australia, December 9. 2021), <https://www.academia.edu/63608978/Turning_the_tables_reassessing_tablature>

Massimiliano Guido, ‘Counterpoint in the Fingers: A Practical Approach to Girolamo Diruta’s Breve & Facile Regola di Contrappunto’, in: Philomusica on-line 11, no. 2 (2012), 64–76, <http://riviste.paviauniversitypress.it/index.php/phi/issue/view/117>

Daniel Heartz, Pierre Attaingnant: Royal Printer of Music (Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1969)

Jacques Moderne, Musicque de Joye, ed. Samuel F. Pogue (Peer: Alamire, 1991)

Craig Monson, ‘Elena Malvezzi’s Keyboard Manuscript: A New Sixteenth-Century Source’, in: EMH 9 (1990), 73–128

Musica Nova: Ricercari, ed. Liuwe Tamminga, Tastature 3 (Colledara, IT, 2001)

Ian Pritchard, ‘Keyboard Thinking: Intersections of Notation, Composition, Improvisation, and Intabulation in Sixteenth-Century Italy’, PhD thesis, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, 2018

Cipriano de Rore, Tutti i madrigali […] spartiti et accomodati per sonar d’ogni sorte d’Istrumento perfetto (Venice: Angelo Gardano, 1577)

Alexander Silbiger, ‘Is the Italian Keyboard “Intavolatura” a Tablature?’, in: Recercare 3 (1991), 81–103

H. Colin Slim, ‘Some Puzzling Intabulations of Vocal Music for Keyboard, ca. 1600, at Castell’Arquato’, in: Five Centuries of Choral Music: Essays in Honor of Howard Swan, ed. Gordon Paine (Stuyvesant, NY, 1988), 127–52

Luigi Ferdinando Tagliavini, ‘The Art of “Not Leaving the Instrument Empty”: Comments on Early Italian Harpsichord Playing’, in: EM 11 (1983), 299–308