Renaissance Keyboards in the Christian Kingdom of Sixteenth-Century Ethiopia1

Janie Cole

How to cite

How to cite

Abstract

Abstract

Keyboards served as essential commodities in early modern European overseas exploration and expansion, and circulated as a motivation of colonial, diplomatic, commercial and religious interests. Yet while we know much about the circulation and use of keyboards in trading centres, missionary and ambassadorial ventures, and educational institutions in the New World and Asia, few studies have focused on their presence, dissemination and cultural functions in sub-Saharan Africa, aside from some traces in the kingdom of Kongo and in South Africa.

Drawing on 15th–17th-century travellers’ accounts, Portuguese dignitaries’ letters, and the voluminous surviving Jesuit documentation, this essay explores the dissemination, musical functions and cultural significance of the earliest documented Western keyboards, including harpsichords, in the Christian kingdom of Ethiopia in the early modern period, exploring themes around musical circulation, keyboards as diplomatic and evangelical tools, and how keyboard music served as a construct for representation, identity, agency and power in Afro-European encounters and colonial perspectives. It draws on two significant encounters between Ethiopia and Latin Europe during the early modern age of exploration, namely some of the earliest documented Ethiopian contacts with European music on Ethiopian soil from both secular and sacred contexts. First, one of the earliest documented encounters between a Portuguese embassy and the Ethiopian royal court of King Lebnä Dengel in 1520 provides significant new insights into the use of European music, a harpsichord and other keyboard instruments for diplomacy and gift-giving, the local faranji (foreigners) community, and arguably the earliest recorded Western keyboards to be brought into Ethiopia in a complex dissemination itinerary from Lisbon to Shewa, via Goa. The 1520 import of a harpsichord to the North-East African highlands appears to be the earliest documented exemplar of the use of a harpsichord as a diplomatic tool in sub-Saharan Africa. Then, encounters between Portuguese Jesuit missionaries from Goa and the Ethiopian indigenous communities during the Jesuit period (1557–1632) on the highlands reveal the import of keyboards for Jesuit missionary strategies and their musical art of conversion, which employed music as both evangelical and pedagogical tools, and blended indigenous and foreign elements.

These Ethio-European musical encounters offer tantalizing views on the spread of keyboard instruments in Portuguese courtly and Jesuit liturgical musical traditions across three continents, and how they served as central components of ambassadorial and evangelical ventures by colonial powers. The sources provide new documentation about how keyboard instruments were transmitted along the Portuguese routes of discovery, allowing the Oriental and Old Worlds to collide in interconnected musical experiences, thus giving broader insight into the role of harpsichords and other keyboards in constructing identity, religion, and the collisions of political, social and cultural hierarchies outside of Europe in an entangled global early modern period. Further investigation is now needed into other African locales to discern how widespread the use of Western keyboards was on the continent and how these were perceived by local indigenous communities in the context of wider Afro-Eurasian encounters and relations in these distant outposts of Renaissance music.

About the Author

About the Author

Janie Cole (PhD University of London) is a Research Scholar at Yale University’s Institute of Sacred Music and Visiting Professor in Yale’s Department of Music (2023–24), Research Officer for East Africa on the University of the Witwatersrand/University of Cape Town’s interdisciplinary project Re-Centring AfroAsia (2018–), and a Research Associate at Stanford University’s Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics (2022–). She will join the University of Connecticut’s Department of Music as an Assistant Professor of Musicology in 2024. Prior to this, she was a Senior Lecturer (adjunct) at the University of Cape Town’s South African College of Music for nine years (2015–23). Her research areas focus on musical practices, instruments and thought in early modern African kingdoms and Afro-Eurasian encounters, transcultural circulation and entanglements in the age of exploration; the intersection of music, consumption and production, politics, patronage and gender in late Renaissance and early Baroque Italy and France; and music and the anti-apartheid struggle in 20th-century South Africa and musical constructions of Blackness, apartheid struggle movement politics, violence, resistance, trauma, and social change. She serves on the Renaissance Society of America Council as founding Discipline Representative in Africana Studies (2019–23), is the co-founder of the international Study Group Early African Sound Worlds sponsored by the International Musicological Society, and is the Founder/ Executive Director of Music Beyond Borders (www.musicbeyondborders.net).

Keyboards served as essential commodities in early modern European overseas exploration and expansion, and circulated as a motivation of colonial, diplomatic, commercial and religious interests. The presence of Western keyboard instruments in the Far East can be traced back to the 13th century, with an organ being sent from an Arab court to China.2 As Jennifer Linhart Wood asserts, organs and other keyboards accompanied European travelers to China, Africa, India, Japan, Turkey and Russia between the 13th through 16th centuries whether for diplomacy, as gifts for foreign rulers, or for use by missionaries.3 Harpsichords, organs and virginals played a significant part in the history of Renaissance oriental diplomacy (especially between c. 1575 and c. 1625), including in musical exchanges and missionary activities in the Ming and Qing courts in Beijing in the early 17th and 18th centuries (from 1601 to 1793), and in Japan by the Jesuits in the 1550s and 1560s.4 And Jesuit and Franciscan missionaries took many portable organs and small harpsichords with them for use in mission schools in the Americas, including Brazil, Ecuador, New Mexico, Peru and Venezuela.5

Yet while we know much about the circulation and use of keyboards in trading centres, missionary activities, ambassadorial ventures and educational institutions in the New World and Asia, few studies have focused on their presence, dissemination and cultural functions in sub-Saharan Africa.6 A much-cited and one of the earliest references to missionary organs taken to the kingdom of Kongo is found in Rui de Pina’s Chronica d’el Rei Dom João II, brought by Portuguese Franciscans who accompanied De Sousa’s expedition there in 1490 and took with them ‘many, very rich ornaments for altars, crosses, candlesticks, bells, vestments, organs’7. A drawing from the early 1650s depicts the king of Kongo, Garcia II (r. 1641–60), on a European throne, accompanied by what Cécile Fromont describes as ‘a royal band of ivory horns, marimbas, harpsichords, tambourines, and an iron bell’ (Fig. 1a).8 While this might have constituted a very early ethnographic visual representation of European harpsichords in Africa, on closer inspection of the drawing it is clear that the reference to ‘harpsichords’ is incorrect: the so-called ‘harpsichord’ in question is, in fact, not a European keyboard at all, but a west African pluriarc (Fig. 1b), and the king of Kongo is surrounded by an ensemble of royal musicians playing indigenous west African instruments.9

Fig. 1a-b: King Garcia II of Kongo and His Attendants, with detail of royal musician playing a west African pluriarc. Detail of Anonymous, People, Victuals, Customs, Animals, and Fruits of the Kingdoms of Africa, c. 1652–63, Rome: Franciscan Museum of the Capuchin Historical Institute, MF 1370. Courtesy of the Capuchin Historical Institute.

In South Africa, keyboards were imported into the Cape after the arrival of Jan van Riebeeck in 1652 and actively used in Cape colonial society and the colonization process.10 A harpsichord was played in 1660 on three separate occasions in aid of diplomatic relations and as a display of European technology between Van Riebeeck and the local indigenous Khoekhoen peoples, which this author believes to be among the earliest accounts of a Western keyboard instrument being played on southern African soil.11 The harpsichord performances in South Africa act upon displays of European identity, refinement and technological capabilities in order to build trade relations between the Dutch East India Company and the Khoekhoen, and to facilitate commercial activities for their trading post at the Cape.

Other examples of the presence of Western keyboards in southern Africa have yet to be uncovered, and it can be assumed that they would have been present in other parts of the continent along European trade networks and routes of exploration, or in areas of missionary activity, such as in Angola and Mozambique. A case of Portuguese keyboards reaching the North-East African highlands over a century earlier in the early 16th century sheds further light on the dissemination and diplomatic functions of keyboards, in particular a harpsichord, on the continent and Afro-European relations during this period. Indeed, the presence of a harpsichord and other keyboards (including an organ) in this early documented encounter of 1520 necessitates a re-evaluation of assertions by other scholars that the earliest accounts of keyboard instruments being used for diplomatic purposes all concern organs.12 It also appears to be the earliest documented exemplar of the use of a harpsichord as a diplomatic tool in Africa.

Fig. 2 The Christian kingdom of Ethiopia, 1400–1550 (Cox Cartographic Ltd., Matteo Salvadore, The African Prester John and the Birth of Ethiopian-European Relations, 1402–1555 [London/New York, 2017], map 5.1).

Drawing on 15th-, 16th- and 17th-century travellers’ narratives, Portuguese dignitaries’ letters, and the voluminous surviving Jesuit documentation,13 this essay explores the dissemination, musical functions and cultural significance of the earliest documented Western keyboards, including a harpsichord, in the Christian kingdom of Ethiopia (Fig. 2) in the early modern period, exploring themes around musical circulation, keyboards as diplomatic and evangelical tools, and how music might have served as a construct for representation, identity, agency and power in Afro-European encounters and colonial perspectives.14 It draws on two significant encounters between Ethiopia and Latin Europe during the early modern age of exploration – namely one of the first documented Ethiopian contacts with European music on Ethiopian soil—to explore some of the earliest recorded musical contacts and exchanges between Ethiopia and Latin Europe from both secular and sacred contexts. First, one of the earliest documented encounters between a Portuguese embassy and the Ethiopian royal court of King Lebnä Dengel (also known as Dawit III and Wänag Sägäd, 1508–40, Fig. 3) at Shewa in 1520 provides insight into the use of European music, a harpsichord and other keyboard instruments for diplomacy and gift-giving, and the first recorded Western musical instruments to have been brought into Ethiopia in a complex dissemination itinerary from Lisbon to Shewa, via Goa. Then, encounters between Portuguese Jesuit missionaries from Goa and the Ethiopian indigenous communities during the Jesuit period (1557–1632) on the highlands reveal the import of keyboards for Jesuit missionary strategies and their musical art of conversion, which employed music as both evangelical and pedagogical tools, and blended indigenous and foreign elements. These musical encounters offer tantalizing views on the spread of keyboard instruments in Portuguese courtly and Jesuit liturgical musical traditions from Lisbon to Goa to the Ethiopian Highlands, and how they were used as ambassadorial and evangelical tools by colonial powers in an intertwined early modern Indian Ocean world where music served to construct identity, agency and religion.

Fig. 3 Cristofano dell’Altissimo, portrait of King Lebnä Dengel, c. 1552–68, Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence.

***

Fig. 4 Title-page of the first edition of Francisco Alvares, Verdadeira informação das terras do Preste João das Indias (Lisbon: Luís Rodriguez, 1540).

The 1520 encounter between a Portuguese embassy and the Ethiopian court was recorded in Francisco Alvares’ (the mission’s chaplain) 1540 account Verdadeira informação das terras do Preste João das Indias, the first published extensive eyewitness account of Ethiopia (Fig. 4).15 While Alvares’ account must be viewed critically given his ignorance of the country he is describing and the imperialist perspectives of the embassy he represented, we also find an account imbued with accuracy and objective, even sympathetic, observations about the kingdom, including musical practices. Alvares provides details of the Portuguese retinue, including a musician; their long journey from Lisbon to the Ethiopian highlands, via Goa, the capital of Portuguese India; the Ethiopian royal court structure and the encounter between Lebnä Dengel and the Portuguese embassy, including musical performances; and the musical instruments that were taken, and their diplomatic functions.16

The Portuguese embassy left Lisbon for Goa on 7 April 1515, and circumnavigated the African continent, with the aim of stopping off at Goa before traveling on to Ethiopia.17 The gifts brought by the embassy matched the interests of earlier Solomonic rulers in their missions to the Latin West, especially for ecclesiastical garments and objects, but notable is the Portuguese King Manuel’s request for two full organs and two organists to be sent to Ethiopia.18 The embassy arrived in Goa in September 1515, but did not land and sailed on to Cananor and Cochin. There they awaited for most of 1516 to embark on their final mission to Ethiopia, which was delayed until early 1520 when they were forced to return to Goa.19 Reports show that the fabulous gifts intended for the Ethiopian negus (king) were also lost in transit, while the rest was eventually looted in Cochin by the governor Lopo Soares de Albergaria and his cronies.20 It is therefore unlikely that the two original organs sent from Lisbon by the king of Portugal ever arrived in Goa, or proceeded on to Ethiopia. Finally, on 13 February 1520, a Portuguese fleet again set out from India, which included the Portuguese embassy of about 17 men headed by a young fidalgo, Dom Rodrigo de Lima (1500–n.a.). It was the biggest European delegation to an Ethiopian king to date, and included a musician, Manoel de Mares, a ‘player of organs’.21 Since De Mares is not mentioned in the original retinue traveling from Lisbon via Cananor and Cochin to Goa, he may have embarked in Goa on the Portuguese galleon bound for Massawa. However, the Portuguese records of 1514–15, which detail the gifts and personnel to be sent to Ethiopia by order of King Manuel I, explicitly state that ‘two organists’ were to be sent,22 therefore it is highly likely that De Mares had originally been hired to be dispatched to Ethiopia by the Ethiopian ambassador Mateus upon his arrival in Portugal in 1514. The choice to bring a musician and painter in the retinue was carefully positioned in the well-known knowledge that the negus, as Krebs argues, had previously requested that Western craftsmen be sent to his realm, primarily from Italy and Aragon;23 though little did the Portuguese know that he already kept a small academy of European artists and probably musicians on the highlands. The presence of a keyboard player was also imperative in order to have the skilled personnel to perform before the Ethiopian king, as they must have assumed that a competent keyboard player would not be found at the Ethiopian court.24 Their now depleted gifts from the Portuguese king included, amongst other items, ‘some organs’ and a clavichord.25 Since the original keyboards from Lisbon were almost certainly lost en route, the present keyboards now heading to Ethiopian soil must have come from Goa, either originally imported to Portuguese India from Europe, or produced in India given the sophisticated skills of Indian craftsmen and the huge supply in manpower of the coastal regions, which served as resources from which the Portuguese and later missionaries were able to mobilize for Ethiopia.

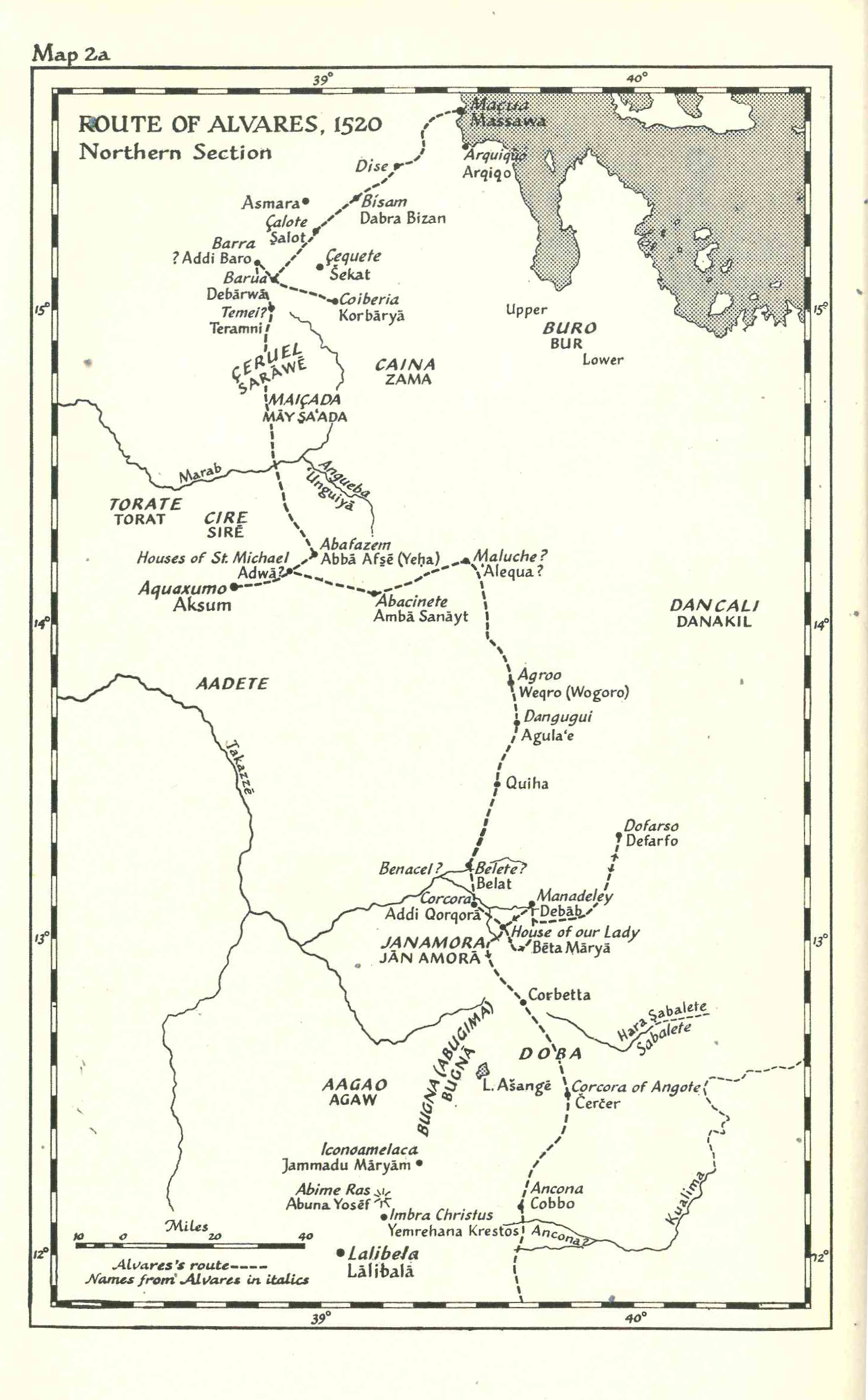

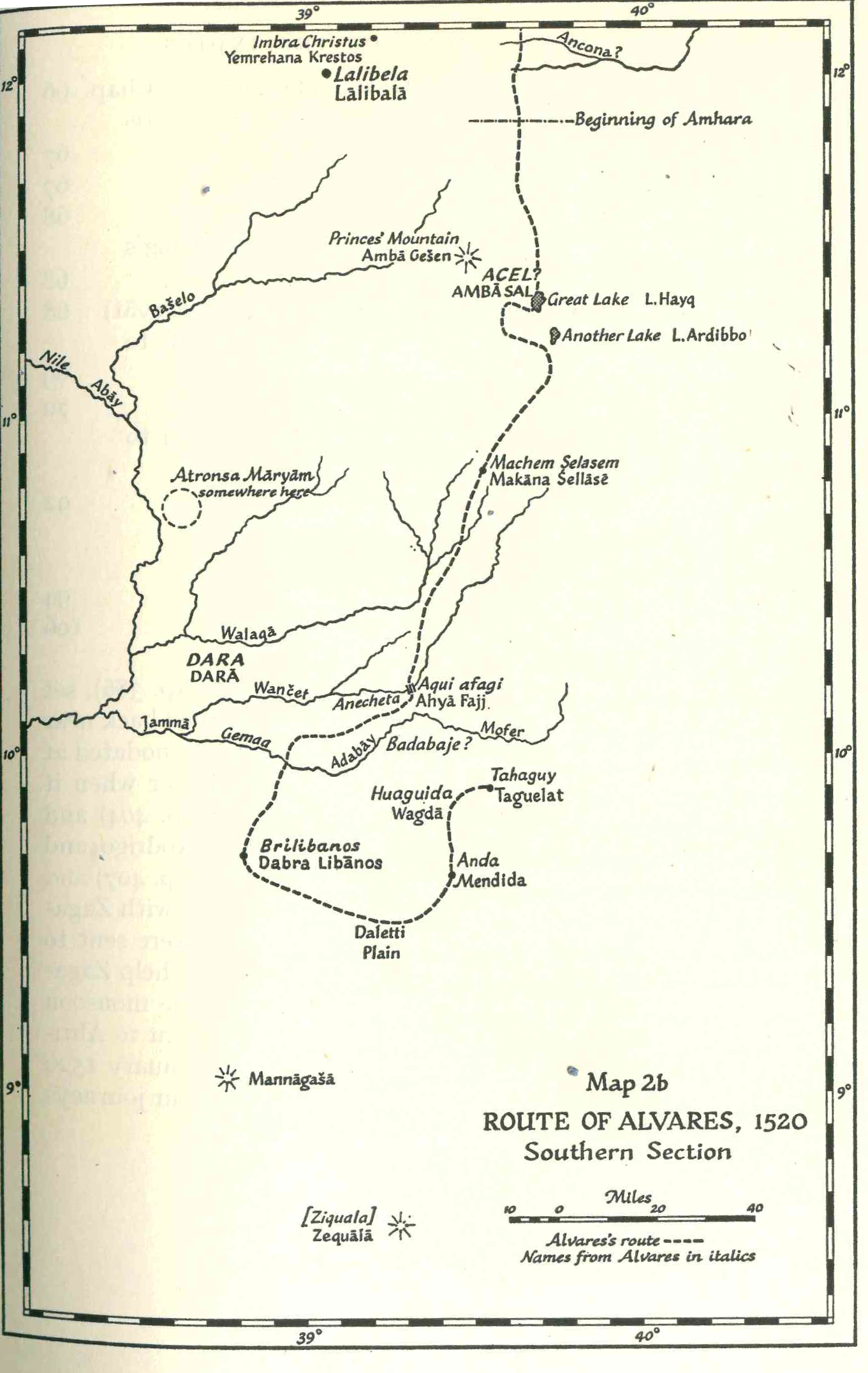

The embassy landed at Massawa, the biggest port on the African littoral, on 9 April 1520 and was shown the way (Figs. 5–6) inland by local Ethiopian troops to reach the highland royal court in Shewa, going via Debarwa, past the Mareb River into Tigray to Adwa, Axum, then south to Shewa, all with the help of the monk Sägga Zä’ab, a major protagonist in later Ethiopian-European relations who served as the king’s ambassador.26 Finally, six months later on 19 October, it arrived at the royal court in Tagulat in northern Shewa, a vast metropolis containing between 20,000 and 40,000 people in an orderly array of multi-coloured tents, hence easily rivaling Europe’s largest capitals.27

Fig. 5 Route of Francisco Alvares in 1520 (Northern Section) (Alvares, The Prester John of the Indies […], ed. Charles F. Beckingham and George W.B. Huntingford [Cambridge, 1961], map 2a).

Fig. 6 Route of Francisco Alvares in 1520 (Southern Section) (Alvares, The Prester John of the Indies […], ed. Charles F. Beckingham and George W.B. Huntingford [Cambridge, 1961], map 2b).

Alvares’ account gives details of the musical encounters and Western keyboard instruments used, presumably to be played by Manoel de Mares, and their various functions in the Portuguese diplomatic processes with the Ethiopian negus. According to Woodfield, this encounter was, in fact, ‘the first recorded instance of the use of keyboards in an overtly diplomatic role in the Portuguese Eastern Empire.’28 It is the opinion of this author that the keyboards mentioned by Alvares are the earliest documented Western keyboards to have been imported to the Ethiopian highlands, perhaps originating from Lisbon (via Goa), or certainly from Goa. It also appears to be the earliest documented exemplar of the use of a harpsichord being used as a diplomatic tool in Africa and perhaps even one of the first documented cases of the use of Western keyboards for diplomatic use on the continent.

It is, however, highly likely that Western keyboards had already reached the royal court prior to October 1520 given the documented presence of faranji (meaning Franks, traditionally used to identify European Catholics) as early as 1402, but almost certainly present in the country decades, if not centuries earlier.29 The establishment of a fully-fledged European community in the late 1420s and early 1430s might have brought, or constructed locally, keyboards, lutes, shawms, viols, harps, flutes, and other 15th-century European instruments.30 One trace in the archival records dates an Italian organ present on the Ethiopian highlands forty years earlier. Francesco Suriano (c. 1450–1530), a Franciscan friar who worked as a missionary in the Holy Land in the early 1480s, recounted in his Treatise on the Holy Land the details of a Franciscan mission from Jerusalem to Ethiopia in 1480–84/85, which included Baptista da Imola, who travelled repeatedly between Jerusalem and Ethiopia in the early 1480s.31 Suriano reported that in late 1481, Baptista da Imola saw ‘an organ made in the Italian style’ in a ‘church of the king [Ba’eda Maryam], who in those days had died’, which was as ‘large as the church of St. Mary of the Angels’ and called ‘Geneth Ioryos’.32 ‘Geneth Ioryos’ is identifiable as the royal church of Gännätä Giyorgis in Amhara founded by king Eskender (r. 1478–94);33 however this church was only founded after the death in 1478 of his father, Ba’eda Maryam, and therefore could not have served as Ba’eda Maryam’s burial place unless he was moved there by 1481. Baptista’s mention that the church containing the Italian organ was the burial place of Ba’eda Maryam would place it as Atronsa Maryam, where the king had been newly buried in 1478 prior to Baptista’s visit. In his Itineraries, Alessandro Zorzi recounts the same story of how Suriano and his companions were ‘amazed’ to find a large painted organ ‘in the Italian style’ in the ‘king’s church where he was buried’ (‘andamo sino alla chiesia dello Re. In la qual de quelli di era stato sepellito. In la qual vedemo uno grande et ornato organo facto alla taliana, et fossimo tuti stupefati’), but dates the visit to 1482 and O.G.S. Crawford identifies the location as the royal church of Atronsa Maryam.34 Crawford also attributes the design and construction of the organ to the Venetian painter-monk, Nicolò Brancaleon (c. 1460–after 1526), one of the most well-known foreign artists in Ethiopia at the time (whom Alvares also met in 1520), who decorated churches including Atronsa Maryam, and thus deduced that ‘doubtless it was he who made that “Italian organ”– surely the first of its kind to be exported – which so naturally surprised our travelers.’35 Hence the organ appears to have been constructed in situ, but there is no hard evidence in the textual sources linking its construction and design to Brancaleon, who had arrived in Ethiopia between 1480 and 1482.36 Brancaleon is a possible candidate for the decoration of the organ given his prominent court status as a painter, his work in the church of Atronsa Maryam, and his presence in Ethiopia before Baptista’s visit.37 Brancaleon, another foreign artist, or a contemporary Ethiopian artist (such as the priest-artist Afnin) belonging to the same artistic circles painting in a European style during 1460–1530 might have been commissioned by the negus Eskender.38 But it is unlikely that he would have known how to construct an organ, an intricate mechanical device, as there is no evidence of him having received any musical training. Rather the 1481/82 Italian organ is more likely to have been constructed by an Italian musician, indicating that Italian and other foreign musicians were almost certainly among the faranji community on the Ethiopian highlands by the second half of the 15th century.39 Whether the 1481/82 Italian organ was designed by Brancaleon or another foreign artist or musician living at the court, it is clear that the Ethiopian court had already been introduced to European keyboards by this time. However, the details given in Alvares’ narrative appear to reveal the first documented keyboards to have been imported to the Ethiopian highlands in 1520 and their use as diplomatic tools.

The three versions of Alvares’ narrative which survive offer slightly different accounts of the European instruments involved in the 1520 musical encounter at the Ethiopian court, though the basic facts are the same. These are Alvares’ original Portuguese account and the version in the first volume of Giovanni Battista Ramusio’s ground-breaking collection of travel narratives, Delle navigationi et viaggi (Venice, 1550), which incorporates another lost source.40 Already noted as accompanying Alvares was Manoel de Mares, ‘player of organs’, and the gifts destined for the court of Lebnä Dengel included ‘some organs’,41 or as Ramusio says ‘un organo’.42 Gift-giving was central to European diplomatic visits to Africa and the East, often in return for the permission to trade, or in this case, where the Portuguese sought an alliance with the Christian Kingdom of Ethiopia in the context of competing Portuguese and Ottoman expansions in the Indian Ocean. The Adali were also asserting their claims in the outskirts of Ethiopia, while the Portuguese and the Ottomans converged on the region.43 Every European institution with interests in Africa and the East was concerned with the choice of suitable objects for presentation on diplomatic voyages. As Ian Woodfield explains, an ideal gift displayed the best aspects of European craftsmanship, mechanical ingenuity and artistry, with costs kept at a low.44 A keyboard instrument met all these requirements. Tracing the historical lineage of keyboards, Woodfield writes that ‘the practice of presenting organs, musical clocks and other automata as diplomatic gifts can be traced back to the 8th-century Byzantine Empire’,45 when an ‘organum’ was sent from Constantinople to Francia by the Byzantine Emperor Constantine V to Pepin, King of the Franks, in 757.46 Further continuities evolved when ‘Western keyboard instruments were sent out to the Far East in the 13th century’ at a time when ‘the Mongol Empire was open to European travelers’. Woodfield surmises that the Portuguese probably rediscovered the attraction of keyboards as musical gifts in their overseas empire in the East through the experiences of Portuguese missionaries who took many portable organs and small harpsichords for use in mission schools.47 Already mentioned are missionary organs taken to the Kongo by Portuguese Franciscans accompanying De Sousa’s expedition in 1490. Woodfield further cites ‘the first portable organ to land on Indian soil was probably an instrument brought by the Franciscans who accompanied Cabral in 1500’.48 The success of gifting these functional instruments may have encouraged more ornate presentation keyboards and at this stage in European history, the organ (as well as the clock) was ‘one of the most technologically advanced objects then in existence’ and ‘the most complex of all mechanical instruments developed before the Industrial Revolution.’49 In the 1520 Ethiopian context, a painted harpsichord could be displayed as an artistic work of art, was (like the organ) an innovative mechanical device with its method of sound production, would undoubtedly have been seen as a novelty on Ethiopian soil, and the costs to produce, transport and hire a musician to accompany it would not have been exorbitant.50 Like the Ethiopian royal drums (nägärit), its visual presence alone was significant and, as Richard Leppert argues in the Indian colonial context, this was as much a ‘totemic function as a musical one’, as the emphasis on sight over sound attributes to music a ‘potential but unrealized practice […] but one nonetheless semantically rich.’51 Leppert even suggests that the high impracticality of having keyboards – being delicate, easily damaged, difficult to maintain, and sensitive to temperature and humidity, especially within the context of a southern African climate – increases their ‘ideological value’ and as expensive pieces of furniture (made of rare materials like exotic woods, ivory or silver) which essentially do not ‘do’ anything, aside from produce a sound which is ethereal, positioned them as ‘perfect signs of social position’ and ‘markers of racial difference.’52 The sound of a plucked stringed keyboard (harpsichord), as opposed to the air-blown mechanism of the organ, would have been a further sonic novelty on the Ethiopian highlands.

The Portuguese visitors were taken to the royal enclosure, however they were not permitted to either see or speak to King Lebnä Dengel, who instead questioned them through his officials. Lebnä Dengel repeatedly summoned and questioned Ambassador Lima, but never revealed himself, even asking Lima to perform for his own amusement. On the night of 3 November, Alvares reported: ‘[The king] sent to say that they should play with sword and shield, and the Ambassador ordered two men of his suite to come out. They did it reasonably well, and yet not as well as the Ambassador desired that things Portuguese should be done […] The Prester could see them very well from behind the curtains, and took great pleasure in it […] After this the Prester John sent to ask that they should sing to a manichord [clavichord], and dance, and they did so.’53 Ramusio refers to the instrument as ‘un organo’, a discrepancy which is probably a simple error.54 The performance with sword and shield served to showcase their military, athletic and tactical prowess, while the request for a musical encounter acts upon discourses in cultural identity, refinement and expertise. While organs and a harpsichord were important as diplomatic gifts, the musical performance itself and communication between the Portuguese musician and his Ethiopian audience were less significant; the Portuguese simply sought approval to get access to the king and to further their political cause.

Wood suggests, in the context of Thomas Dallam’s organ in the Ottoman empire, that the instrument is not merely an object of commercial or musical exchange, but instead early modern cross-cultural encounters at sonic events created soundwaves that ‘calibrate everything on the same frequency of vibration’, producing what she theorizes as the ‘sonic uncanny’, which offers a new framework to consider these intercultural interactions beyond the categories of Western musical theory, mimicry or colonization projects, rather ‘conceptualized as a vibrating wave calibrating bodies on the same frequency.’55 In this way, as Wood clarifies, ‘the vibrating sonic uncanny makes the foreign familiar through the connective soundwave’, so the Portuguese embassy’s harpsichord performance had a physical impact on the space where it was played and on the indigenous audience if we consider sound ‘as a vibrating wave that touches all matter present at a sonic event […] networks or assemblages are formed among bodies, objects, and environments as they are attuned to the same frequency of vibration’, and as a result it creates the sensation of experiencing the foreign and the familiar simultaneously and ‘blurs the demarcation between the familiar and the foreign, the self and the “other”’.56 The instrumental performance on the highlands can thus be seen as one of colonial expansion by sonically claiming and altering a space, as the sound of the instrument moved bodies present where it was played ‘quite literally along the same wavelength, changing them in the process.’57 However, unlike the 1660s context of harpsichord and keyboard performances in South Africa where keyboards were used as an aggressive display of power in the Cape, the 1520 encounter was very clearly structured on the Ethiopians’ own terms from the outset: Lebnä Dengel demonstrated active agency by acting independently and exerting his power over the embassy by turning down its repeated appeals for an audience; not revealing himself for weeks on end and only communicating through his officials; humiliating them by seeming to advance, only to suddenly hinder their mission; and turning his Portuguese guests into objects of entertainment and curiosity.58

As relations between the embassy and negus developed over the coming months, other musical encounters ensued. On 17 January 1521, the Portuguese performed a vocal piece accompanied by the harpsichord: ‘The whole of this tent was spread with very beautiful carpets, and it was large like a reception room […] The Prester sent to tell us to sing and dance after our fashion, and to enjoy ourselves. Then our people began to sing songs to a harpsichord which we had here, and afterwards dance and sing all together.’59 Ramusio also confirms the instrument: ‘Subito li nostri cominciarono à cantar canzoni in un clavocimbalo, che havevamo portato noi.’60 Thus, it is clear that the Portuguese brought several instruments: organs (as confirmed by both Alvares and the Carta das Novas)61 and a string keyboard, whether a harpsichord and/or a clavichord. The exact identification of the string keyboard is difficult to ascertain, as Woodfield says, ‘since confusion between the terms for the harpsichord (‘cravo’) and the clavichord (‘manicordio’) is commonplace in accounts written by non-musician travellers’, as, indeed, were both Alvares and Ramusio.62 Both Alvares and the Carta das Novas concur that the musician carried a clavichord, so perhaps Ramusio mistranslated the term. In any case, as Woodfield also concludes, it is likely ‘that the harpsichord or clavichord was played during the secular entertainments’, while ‘the organ was [probably] reserved for the celebration of Mass’, and also in this case as a gift.63

Most members of the Portuguese embassy finally left Ethiopia in 1526, back to Portuguese Goa, having left Shewa for the coast in 1521. The keyboard player, Manoel de Mares, was presumably with the party, and it is unknown whether he left his keyboard instruments behind at the Ethiopian court. By the mid 16th century, harpsichords and organs were used regularly as diplomatic gifts throughout the Portuguese Eastern Empire. Francis Xavier presented keyboards in Japan in 1551, which according to Woodfield, precipitated an influx of small keyboard instruments into Japan thereafter, where Western musical instruments were sought intensively.64 In the context of missionary ventures, harpsichords, organs and clavichords are mentioned extensively in numerous letters by Jesuit missionaries working in various parts of the world, such as in Japan during the 1560s and 1570s,65 in China at the Ming and Qing courts in the early 17th century,66 and in Portuguese Goa, for example in 1558, when the Viceroy joined the Jesuit Colégio de São Paulo and held magnificent public processions on the Feast of the Virgin, with Portuguese fidalgos, litters, parasols, Portuguese pages, Mozambican slaves, and bands of musicians ‘playing shawms, drums, trumpets, flutes, viols and a harpsichord.’67 The musical education at the Colégio de São Paulo in Goa, considered by 1560 the most influential Jesuit institution in the East, included instrumental learning on the organ, harpsichord and the viol.68 Portuguese missionaries took many portable organs and small harpsichords for use in mission schools abroad.69

Likewise, music and keyboard instruments played a central role in Jesuit musical practices on the Ethiopian highlands at Catholic seminars and services, especially after the Ethiopian kingdom briefly became Catholic from 1624 to 1632 following King Susenyos’ (1606–32) conversion.70 In c.1550, Ignatius of Loyola (co-founder of the Society of Jesus) instructed those Jesuit missionaries going to Ethiopia to found a chapel with a choir and organs if the Ethiopian king so permitted.71 Luís Cardeira (1585–1640), who arrived on the highlands in 1624 with several instruments (including viols, bandurria, a harp and an organ), was a skilled musician and keyboard player of organs, harpsichord and clavichord, who founded a choir at the Gorgora residence72 and taught polyphonic singing, multiple instrumental playing and instrument-making.73 The Jesuits set up educational programs teaching catechism, reading, writing and mathematics in Feremona and Gorgora from 1608 onwards, and music was incorporated to teach Christian spirituality and doctrine, as well as for children to sing and play in the divine offices and at other religious festivities. At the church of Gorgora Iyäsus during Easter week, the Laudate Dominum and Magnificat psalms were sung accompanied by an organ.74 In 1624, the Jesuit father Manoel de Almeida visited the king at Dänqäz (the royal camp) and brought ‘organs, which Father Luís Cardeira played skilfully, then the harp, harpsichord and other musical instruments, which he [the king] greatly applauded.’75 Western keyboards, including harpsichords and clavichords, were therefore both imported into the Ethiopian highlands from the mid 16th century and fabricated locally.

***

The evidence of these earliest documented European keyboards, including a harpsichord, organs and a clavichord, in the Christian kingdom of Ethiopia in 1520 points to the importance of musical performance and keyboard instruments specifically as central components in European, in this case Portuguese, overseas diplomatic discourses in Africa. Music served as a construct for identity, agency and power by both Europeans and Ethiopians in the earliest documented musical encounters that survive between Ethiopia and Latin Europe.76 Their interactions reveal an Afro-European story of mobility and migration which offers insights into the workings of an intertwined early modern Indian Ocean world that reached across three continents, from Lisbon to Shewa, via Goa. When the Portuguese mission finally reached the Ethiopian royal court after a century of relentless efforts in search of the fabled Prester John, one of the most surprising aspects of the Ethiopian kingdom was the existence of a faranji community and several well-integrated Europeans living and detained there as subjects. The existence of this foreigners’ community – which almost certainly included foreign musicians given the presence of the 1481/82 Italian organ – in 15th- and 16th-century Ethiopia adds to wider scholarship that dispels the Ethiopian isolation paradigm as it demonstrates the circulation of European musical knowledge in the Indian Ocean world and that Christian Ethiopians of the highlands were not only an integral part of the Red Sea world, but also that they welcomed foreigners, especially those with technology and artistic accomplishments – both qualities that are embodied in European musicians, musical performance and keyboards. Whether the harpsichord, clavichord and organs brought by the 1520 Portuguese embassy to the Ethiopian court were, in fact, the earliest exemplars to be brought into the highland kingdom and North-East Africa, or merely the earliest documented exemplars, the Ethiopian court had officially been introduced to Western keyboards – beyond the 1481/82 Italian organ constructed locally and found in a local prestigious royal church – and early modern European music and technology. It also appears to be the earliest documented exemplar that we have so far of the use of a harpsichord as a diplomatic tool in sub-Saharan Africa. These early Afro-European musical contacts offer views on the spread of Portuguese musical traditions and instruments along the Portuguese routes of exploration, giving broader insight into the role of music in constructing and defining identity and cultural hierarchies by colonial powers in early modern North-East Africa. Further research on early Western keyboard instruments in Ethiopia should explore iconography and iconological questions, as a closer look at paintings, mural illustrations and manuscript drawings might yield visual representations of Western keyboards. It is unlikely that harpsichords, clavichords and organs from 1520 or the later Jesuit period would have survived after the devastating impact of the invasion by the Sultanate of Adal headed by Ahmad ibn Ibrahim al-Ghazi the Grañ (1506–43) in the mid-late 1520s,77 which saw the destruction of churches and monasteries, plundering of precious materials, massacre of priests and monks, and almost surely destroyed what musical instruments and cultural artefacts were on the highlands from either side of the Ethio-Portuguese encounter. In the later Jesuit period, very little material culture has survived since the missionaries’ expulsion saw their residences looted, temples desecrated and the buildings partly or totally destroyed.78 The Jesuits themselves claimed to have destroyed many of their possessions to prevent the Ethiopians from doing the same, and only a few valuable items might have been taken back to India.79 For any artefacts that did survive the Jesuit expulsion, climatic conditions, parasites and a lack of maintenance would probably have left them to decay in any case. Further investigation is now needed into other sub-Saharan African locales to discern how widespread the use of Western keyboards, especially harpsichords, was on the continent and how these were perceived by local indigenous communities in the context of wider Afro-Eurasian encounters and relations in these distant outposts of Renaissance music.

Endnotes

Bibliography

Manuel de Almeida, Historia Aethiopiae, in: Camillo Beccari (ed.), Rerum Aethiopicarum Scriptores Occidentales Inediti a Saeculo XVI ad XIX, 14 vols. (Rome, 1903–1917), vi

Manuel de Almeida, Some Records of Ethiopia 1593–1646: Being Extracts from the History of High Ethiopia or Abassia, by Manoel de Almeida, together with Bahrey’s History of the Galla, ed. C.F. Beckingham and G.B.W. Huntingford (London, 2010), 109–32

Francisco Alvares, Verdadeira informação das terras do Preste João das Indias (Lisbon: Luís Rodriguez, 1540)

Francisco Alvares, The Prester John of the Indies. A True Relation of the Lands of the Prester John, Being the Narrative of the Portuguese Embassy to Ethiopia in 1520, Written by Father Francisco Alvares, ed. Charles F. Beckingham and George W.B. Huntingford (Cambridge, 1961)

Jean Aubin, ‘Le prêtre Jean devant la censure portugaise’, in: Bulletin des Études Portugaises et Brésiliennes 41 (1980), 33–57

Deresse Ayenachew, ‘The Southern Interests of the Royal Court of Ethiopia in the Light of Berber Maryam’s Ge’ez and Amharic Manuscripts’, in: Northeast African Studies 11, no. 2 (2011), 43–57

Deresse Ayenachew, ‘Territorial Expansion and Administrative Evolution under the “Solomonic” Dynasty’, in: A Companion to Medieval Ethiopia and Eritrea, ed. Samantha Kelly (Leiden, 2020), 57–86

Cates Baldridge, Prisoners of Prester John: The Portuguese Mission to Ethiopia in Search of the Mythical King, 1520–1526 (Jefferson, NC, 2012)

Camillo Beccari (ed.), Rerum Aethiopicarum Scriptores Occidentales Inediti a Saeculo XVI ad XIX, 14 vols. (Rome, 1903–1917)

Francesco Béguinot, La cronaca abbreviata d’Abissinia: nuova versione dall’Etiopico e commento (Rome, 1901)

Theophilus Bellorini, Eugene Hoade and Bellarmino Bagatti (eds.), Treatise on the Holy Land (Jerusalem, 1949)

Olivia Bloechl, ‘The Catholic Mission to Japan, 1549–1614’, in: The Cambridge History of Sixteenth-Century Music, ed. Iain Fenlon and Richard Wistreich (Cambridge, 2019), 163–75

Olivia Bloechl, ‘Music in the Early Colonial World’, in: The Cambridge History of Sixteenth-Century Music, ed. Iain Fenlon and Richard Wistreich (Cambridge, 2019), 128–57

Ian Campbell, ‘A Historical Note on Nicolò Brancaleon: as Revealed by an Iconographic Inscription’, in: Journal of Ethiopian Studies 37, no. 1 (2004), 83–102

Marzia Caria (ed.), ‘Il Tratatello delle indulgentie de Terra Sancta secondo il ms. 1106 della Biblioteca Augusta di Perugia. Edizione e note linguistiche’, PhD thesis, Università degli Studi di Sassari, 2008

Enrico Cerulli, ‘L’Etiopia del secolo XV in nuovi documenti storici’, in: Africa Italiana 5 (1933), 57–112

Stanislaw Chojnacki, ‘Notes on Art in Ethiopia in the 15th and Early 16th Century’, in: Journal of Ethiopian Studies 8, no. 2 (1970), 21–65

Stanislaw Chojnacki, Major Themes in Ethiopian Painting: Indigenous Developments, the Influence of Foreign Models and their Adaptation from the 13th to the 19th Century (Wiesbaden, 1983)

Stanislaw Chojnacki and Carolyn Gossage, Ethiopian Icons: Catalogue of the Collection of the Institute of Ethiopian Studies Addis Ababa University (Milan, 2000)

Victor Coelho, ‘Connecting Histories: Portuguese Music in Renaissance Goa’, in: Goa and Portugal: Their Cultural Links, ed. C. Borges, S. J. and Helmut Feldmann, Xavier Centre of Historical Research Series 7 (New Delhi, 1997), 131–47

Leonardo Cohen, ‘Cardeira, Luís’, in: Encyclopaedia Aethiopica, ed. Siegbert Uhlig, vol. 1: A-C (Wiesbaden, 2003), 686

Leonardo Cohen, The Missionary Strategies of the Jesuits in Ethiopia (1555–1632) (Wiesbaden, 2009)

Janie Cole, ‘Traces of Renaissance Keyboards in Early Modern Sub-Saharan Africa’ (forthcoming)

Janie Cole, ‘Constructing Racial Identity and Power in Music, Ceremonial Practices and Indigenous Instruments in Early Modern African Kingdoms’, in: The Routledge Companion to Race in Early Modern Artistic, Material and Visual Production, ed. Nicholas R. Jones, Christina H. Lee and Dominique Polanco (forthcoming 2024)

Janie Cole, ‘Jesuit Missionaries, the Musical Art of Conversion and Indigenous Encounters in the Christian Kingdom of Ethiopia (1557–1632)’, in: Music in Africa and its Diffusion in the Early Modern World, ed. Janie Cole and Camilla Cavicchi (Turnhout: Brepols, forthcoming 2024)

Janie Cole, ‘Not a disagreeable sound: Music, Diplomacy and Foreign Encounters at the Court of Lebnä Dengel in 16th-Century Ethiopia’ (forthcoming 2024)

Gaspar Correia, Lendas da India [c. 1560], vols. 2–4 (Nendeln, 1976)

O.G.S. Crawford, Ethiopian Itineraries Circa 1400–1524 (Cambridge, 1958)

Anne Damon-Guillot, ‘Toucher le cœur des schismatiques: Stratégies sonores et musicales des jésuites en Éthiopie, 1620–1630’, in: Le Jardin de Musique. Revue de l’Association Musique ancienne en Sorbonne 6, no. 1 (2009), 65–99

Anne Damon-Guillot, ‘Sounds of Hell and Sounds of Eden. Sonic Worlds in Ethiopia in the Catholic Missionary Context, 17th–18th Centuries’, in: Toward an Anthropology of Ambient Sound, ed. Christine Guillebaud (New York, 2017), 39–55

Marie-Laure Derat, Le domaine des rois éthiopiens, 1270–1527: Espace, pouvoir et monarchisme (Paris, 2003)

Aida Fernanda Dias, ‘Um presente régio’, in: Humanitas 47 (1995), 685–789

Erik Dippenaar, ‘Conquering the Cape: the Role of Domestic Keyboard Instruments in Colonial Society and the Colonisation Process’, Ph.D. thesis, University of Cape Town, 2021

Gianfranco Fiaccadori, ‘Venezia, l’Europa e l’Etiopia’, in: Nigra sum sed formosa. Sacro e bellezza dell’Etiopia cristiana (Venezia, Ca’ Foscari, 13 marzo–10 maggio 2009), ed. Giuseppe Barbieri and Gianfranco Fiaccadori (Vicenza, 2009), 27–48

Cécile Fromont, The Art of Conversion: Christian Visual Culture in the Kingdom of Kongo (Chapel Hill/Williamsburg, Virginia, 2014)

William Brooks Greenlee, The Voyage of Pedro Alvares Cabral to Brazil and India: From Contemporary Documents and Narratives (London, 1938)

Eta Harich-Schneider, A History of Japanese Music (Oxford, 1973)

Marilyn E. Heldman, ‘Brancaleone, Nicolò’, in: Encyclopaedia Aethiopica, ed. Siegbert Uhlig, vol. 1: A-C (Wiesbaden, 2003), 620–1

Ronald J. Horvath, ‘The Wandering Capitals of Ethiopia’, in: The Journal of African History 10 (1969), 205–19

Verena Krebs, ‘Windows onto the World: Culture Contacts and Western Christian Art in Ethiopia, 1402–1543’, PhD thesis, Universität Konstanz/Mekelle University, 2014

Verena Krebs, Medieval Ethiopian Kingship, Craft, and Diplomacy with Latin Europe (Cham, 2021)

Manfred Kropp, Die Geschichte des Lebna-Dengel, Claudius und Minas (Leuven, 1988)

Manfred Kropp, ‘The Ser’atä Gebr: A Mirror View of Daily Life at the Ethiopian Royal Court in the Middle Ages’, in: Northeast African Studies 10, nos. 2–3 (1988), 51–87

Renato Lefèvre, ‘Riflessi etiopici nella cultura europea del Medioevo e del Rinascimento (Parte I)’, in: Annali Lateranensi 8 (1944), 9–89

Renato Lefèvre, ‘Riflessi etiopici nella cultura europea del Medioevo e del Rinascimento (Parte II)’, in: Annali Lateranensi 9 (1945), 331–444

Renato Lefèvre, ‘Riflessi etiopici nella cultura europea del Medioevo e del Rinascimento (Parte III)’, in: Annali Lateranensi 11 (1947), 255–342

Richard Leppert, The Sight of Sound: Music, Representation and the History of the Body (Berkeley, 1995)

Joyce Lindorff, ‘Missionaries, Keyboards and Musical Exchange in the Ming and Qing Courts’, in: EM 32 (2004), 403–14

David Lopes, Chronica dos Reis de Bisnaga (Lisbon, 1897), trans. into English in Robert Sewell, A Forgotten Empire (Vijayanagar) (London, 1900)

Hiob Ludolf, Historia aethiopica, sive Brevis & succincta descriptio regni Habessinorum (Frankfurt a.M.: Joh. David Zunner, 1681)

Giuseppe Marcocci, ‘Gli umanisti italiani e l’impero portoghese: una interpretazione della Fides, Religio, Moresque Aethiopum di Damião de Góis’, in: Rinascimento 45 (2005), 347–9

Andreu Martínez d’Alòs-Moner, Envoys of a Human God: The Jesuit Mission to Christian Ethiopia, 1557–1632 (Leiden, 2015)

Franz-Christoph Muth, ‘Ahmad b. Ibrahim al-Gazi’, in: Encyclopaedia Aethiopica, ed. Siegbert Uhlig, vol. 1: A-C (Wiesbaden, 2003), 155–8

Barbara Owen, Peter Williams and Stephen Bicknell, ‘Organ’, in: Grove Music Online, <https://doi.org/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.44010>

Gasparo Páez, Lettere annue di Etiopia del 1624, 1625 e 1626. Scritte al M.R.P. Mutio Vitelleschi Generale della Compagnia di Giesù (Rome, 1628)

Richard Pankhurst, An Introduction to the Economic History of Ethiopia, from Early Times to 1800 (London, 1961)

Richard Pankhurst, ‘Färänǧ’, in: Encyclopaedia Aethiopica, ed. Siegbert Uhlig, vol. 2: D-HA (Wiesbaden, 2014), 492

Jean Perrot, The Organ from its Invention in the Hellenistic Period to the End of the Thirteenth Century, trans. by Norma Deane (London, 1971)

Ruy de Pina, Chronica d’El Rei Dom Joaõ II (Lisbon, 1792)

Giovanni Battista Ramusio, Delle navigationi et viaggi (Venice: Heredi di Lucantonio Giunti, 1550)

Robert Ross, A Concise History of South Africa (Cambridge, 2008)

Matteo Salvadore, The African Prester John and the Birth of Ethiopian-European Relations, 1402–1555 (London/New York, 2017)

Matteo Salvadore and Gianfranco Fiaccadori, ‘Brocchi, Giovanni Battista’, in: Encyclopaedia Aethiopica, ed. Siegbert Uhlig, vol. 5: Y-Z, Supplementa, addenda et corrigenda (Wiesbaden 2014), 284–6

Robert Sewell, A Forgotten Empire (Vijayanagar) (London, 1900)

Robert Stevenson, ‘The Afro-American Musical Legacy to 1800’, in: MQ 54 (1968), 475–502

Henry Thomas and Armando Cortesāo, The Discovery of Abyssinia by the Portuguese in 1520: A Facsimile (London, 1938)

Jan Anthonisz Van Riebeeck, Journal of Jan Van Riebeeck, ed. H.B. Thom, trans. by C.K. Johnman and A. Ravenscroft, 3 vols. (Cape Town/Amsterdam, 1952)

J. Vaz de Carvalho, ‘Cardeira, Luís’, in: Diccionario historico de la Compania de Jesus, ed. Charles E. O’Neill and Joaquín Ma. Domínguez (Madrid/Rome, 2001), 652

David B. Waterhouse, ‘The Earliest Japanese Contacts with Western Music’, in: Review of Culture 26 (1996), 36–47

Peter Williams, ‘Organ’, in: New Grove, xiii, (London 1980), 710–79

Akalou Wolde-Michael, ‘The Impermanency of Royal Capitals in Ethiopia’, in: Yearbook of the Association of Pacific Coast Geographers 28 (1966), 146–56

Jennifer Linhart Wood, ‘An Organ’s Metamorphosis: Thomas Dallam’s Sonic Transformations in the Ottoman Empire’, in: Journal for Early Modern Cultural Studies 15, no. 4 (2015), 81–105

Ian Woodfield, ‘The Keyboard Recital in Oriental Diplomacy, 1520–1620’, in: JRMA 115 (1990), 33–62

Ian Woodfield, English Musicians in the Age of Exploration (New York, 1995)

Felix Zabala Lana, ‘Cardeira, Luis’, in: Músicos jesuitas a lo largo de la historia (Bilbao, 2008)