Fabio Antonio Falcone

How to cite

How to cite

Abstract

Abstract

Andrea Antico’s 1517 print of keyboard intabulations of frottolas is rather well known to modern scholars, mostly because it is the first print of keyboard repertoire in Italy. Frottolas were a codified genre where a strophic text often predated the music and followed strict literary rules. Since Antico published instrumental arrangements, the texts are not immediately visible, yet they were very well known to the reader of those days. How was the music then performed when no text was heard? How was this monodic repertoire understood by the contemporaries? Did the player infer the correct accentuation of the music from an implicit text? If so, a correct understanding of the meter and of poetical conventions would be an essential element for an adequate performance of Antico’s arrangements of this vocal repertoire.

About the Author

About the Author

Fabio Antonio Falcone is a performer specialized in Renaissance and early Baroque repertoire. He is especially interested in 16th-century Italian keyboard music, as well as vocal and instrumental repertoire of the Baroque period. He performs as a soloist and continuo player at international venues and festivals such as MITO Festival, Early Music Festival Bad Arolsen, Maison de la Radio France, Fondazione Giorgio Cini Venice. He studied in the Netherlands with Bob van Asperen, in Italy with Maria Luisa Baldassari and Jesper Bøje Christensen, and in Switzerland with Francis Biggi. He devotes himself to research in music didactics, in particular to the reconstruction of teaching practices from the analysis of historical sources. He is currently a member of the research group in didactics of arts (DAM) and lecturer in didactics of music at the University of Geneva.

Outline

Outline

This article proposes a hypothetical way to conceive the interconnection between music and text in specific cases where the text is missing, such as in Andrea Antico’s Frottole intabulate da sonare organi, libro primo (1517). First, I will present the subject and the research questions. Second, I will illustrate the methodology employed for the analysis of the repertoire. Finally, I will discuss the conclusions of this investigation. Special attention will be given to the specific aspects of performance practice that are involved.

1. The Interconnection between Text and Music in the frottola Genre

In 1517 Andrea Antico published a set of keyboard arrangements of vocal pieces.1 This publication is well known to modern scholars because it is the first example of printed keyboard repertoire in Italy.2

The pieces arranged in the collections are frottolas. The generic term frottola designates a set of fixed-form poems set to music in a significant variety of poetic structures. Though frottolas were most often composed in four separate parts, many historical records show that they were mostly performed by one singer accompanying himself or herself on the lute.3 In this repertoire, the same music is frequently set to different texts, as in the case of other poetic forms like strambotti where often only the music for the first two verses is provided. Furthermore, in his Libro quarto (1505) (RISM 15055) Petrucci includes the music of an aer da cantar versi latini (air to sing Latin verses) and a modo de cantar sonetti (air to sing sonetti) without providing any text, which indicates that in this repertoire the music is a neutral medium for declamation of different texts.4

As stated by Coelho and Polk, there can be several motivations behind the composition of an intabulation which determine its function and essence. Drawing a parallel with the practice of translation, the authors state that intabulations can cover a wide range of approaches: from faithful rendition of the original model to simple quotation of main themes. The motivations of the composer/arranger and the ensuing features of the intabulation are closely determined by the recipient or dedicatee of the work.5

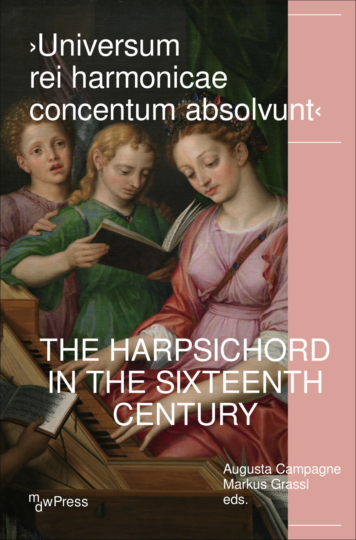

In the case of Andrea Antico’s collection, it is plausible to assume that the main recipients were the highest-ranking members of the courts of the Italian peninsula. The keyboard instruments represented in the wooden inlays in the studiolo of Federico da Montefeltro and Isabella d’Este show the growing interest in these instruments by the most discerning musical patrons of the 16th century.

Giovanni de’ Medici, who later became Pope Leo X, also commissioned inlays. He owned several keyboard instruments and was himself a skilled instrumentalist and seems to have had a talent for singing.6 As a young man he was initiated into music by the Flemish composer Heinrich Isaac.7 During his years of musical training at the court of his father Lorenzo the Magnificent, the young Giovanni de’ Medici had the opportunity to listen to the greatest improvisers of the time, who used to recite poems accompanied by the lyre or lute. Baggio Ugolini (the main actor in the Mantuan performance of Poliziano’s Orfeo), Aurelio Brandolini (improviser of vernacular and Latin verses), and Cardiere (known for his talent as an improviser of verses on the lyre) were all received on several occasions at the court of Lorenzo il Magnifico during Giovanni’s years of training.8

Antico published an instrumental version of twenty-six frottolas, wherein no text was included. Most likely these pieces were well-known as vocal works to his public, since the collection contains tablatures of frottolas that had been circulating since 1507 in collections published by Petrucci and Antico himself.9

Contemporary sources confirm that singers of frottolas were supposed to base their performances on the content of the lyrics.10 Singers were expected to be aware of the poetic content and the literal meaning of the text. They had also to be aware of the form and structure, which includes the metre of the lyrics.

Brunetto Latini (1220–1294) distinguished ‘the speaking in prose’ from ‘the speaking in verses’ in his Li livres dou Tresor. He states that speaking in verses is governed by three parameters: weight, number and measure. Whoever whishes to speak in rhyme must count out all the syllables with his fingers in order to be sure that the verse has the right number. He must measure the last two syllables of each verse, in order to make the rhyme work properly. Finally, and most importantly, he must respect the correct accentuation of the words in order to make the rhymes and the rhythm of the verse work properly.11 Thus, Brunetto Latini tells us that the right accentuation of syllables was strictly respected while reading verses, as early as the 1260s.

Modern Italian poetry is based on the quality of the syllables, which can be strong or weak, rather than their quantity, as in the case of Latin poetry.12 In Latin poetry the length of the syllable was the building block of the metre and the accent had no structural importance. In Italian poetry the rhythm is the product of the arrangement of arsis and thesis – that is, tonic (stressed) syllables and unstressed syllables.13 The quantity of syllables was not perceived anymore, and the tonic accent was the only important element.

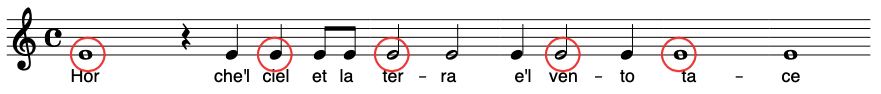

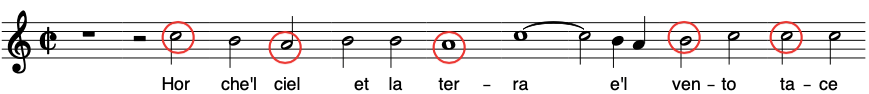

Stefano La Via states that when we set an Italian text to music, the syllable automatically becomes quantitative: longer notes for accented syllables.14 From 1550 onward, accented syllables were set to music chiefly with long notes and on downbeats. This is the case for most madrigals from the second half of the 16th century onward. However, frottolas are very different. We often note discrepancies between the metric structure (the accents of the verse) and the music. For instance, we find strong tonic accents set to weak parts of the measure, often on upbeats. An example is the first endecasillabo15 of Petrarch’s Hor che’el ciel et la terra set to music by Monteverdi and then the version by Tromboncino. The metrical reading of the verse is:

Hor che ’l ciel et la terra e ’l vento tace (-u,-uu,-u,-u,-u).16

Ex. 1: Claudio Monteverdi, ‘Hor che’l ciel et la terra’ (SV 147), in: Madrigali guerrieri, et amorosa […] Libro ottavo (Venice: Alessandro Vincenti, 1638) mm. 1–6.

Ex. 2: Bartolomeo Tromboncino, ‘Hor che’l ciel et la terra’, in: Frottole libro secondo (Rome: Andrea Antico?, c. 1516) (RISM [c. 1516]10), mm. 1–6.

In the Monteverdi example, the music respects the metrical structure of the verse. The same is not the case in the frottola of Tromboncino. In the seconda prattica, the music was at the service of the text, amplifying the metrical structure and the meaning of the lyrics. But in the case of frottolas the music often seems to be nothing more than a neutral medium for reading the text out loud, in a sort of declamation. It is particularly interesting that Vincenzo Calmeta, a follower and biographer of Serafino dall’Aquila, encourages young lovers who want to conquer ladies through their singing to choose frottole, stanze or barzellette over genres with skilfully crafted diminutions, in order to better understand the text.17 Calmeta suggests following the example of Cariteo or Serafino: to imitate ‘the judgement of a discerning jeweller, who, having to show the finest and whitest pearl, will place it not on a golden cloth, but on some black silk, that it might show up better’.18

Therefore, in frottola repertoire the music seems to have been a blank canvas for performing any text; the music was conceived as a generic structure over which different texts could be sung. This would also explain why different texts are often set in music with the same or very similar musical material. In the next examples, the first two verses from Petrarch’s sonetto ‘Hor che’l ciel et la terra’ and from the anonymous strambotto ‘Zephyro spira’, are both set to music by Tromboncino: they show almost identical musical material despite the different texts.

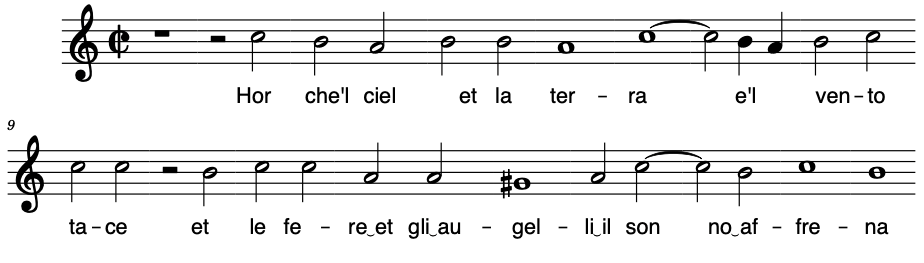

Ex. 3: Bartolomeo Tromboncino, ‘Hor che’l ciel et la terra’, in: Frottole libro secondo (Rome: Andrea Antico ?, c. 1516) (RISM [c. 1516]10), mm. 1–10.

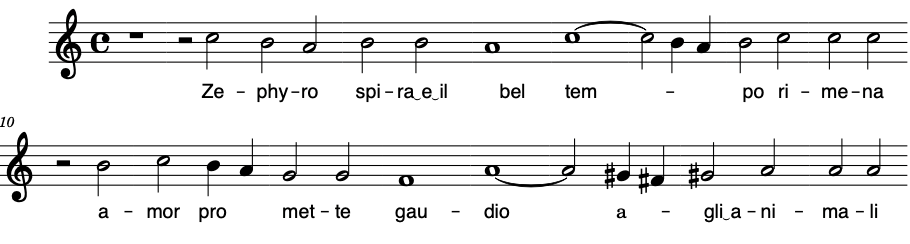

Ex. 4: Ex. 4: Bartolomeo Tromboncino, ‘Zephyro spira’, in: Frottole libro octavo (Venice: Ottaviano Petrucci, 1507) (RISM 15074), mm. 1–10.

A similar kind of melodic line can be found in other guises, such as the first verse of Petrarch’s canzona Che debbio far, set to music by Tromboncino.

Ex. 5: Bartolomeo Tromboncino, ‘Che debb’io far’, in: Canzoni novi con alcune scelte di vari libri di canto (Rome: Andrea Antico, 1510) (RISM 15101), mm. 1–6.

We find a number of melodic formulas in the frottola repertoire, called aere or modi19, and each of these formulas fits a different kind of metre. This allows us to find musical formulas for almost any kind of verse.20

Similar relationships exist between text and music in the ottava rima, where stereotyped melodic formulas reflect its improvisatory origin. The sung ottava rima is a popular practice still surviving in Tuscany, with the improvisation of Italian endecasillabi while singing standard musical patterns. The performers are familiar enough with the musical patterns that they can use them to sing different texts. As we can still hear in Tuscany today, the sung ottava rima has always been improvised in a way that lies between folk and literary tradition.21 The lyrics are improvised on a musical formula called aere, which works as a fixed musical structure to help the poet to compose the texts with the right number of syllables and without the need to count them out.

Renaissance frottolas, as we have seen, are similar: Pirrotta already pointed out that frottolas owe their form to a folkloric oral tradition, though they are a nobler and more refined version of this tradition. Frottolas were equally a product of the cultivated North Italian Courts and a creation for their use.22

Like the ottava rima, frottolas are based on the aere musical formulas. Frottola repertoire is mainly monodic; the use of polyphony is limited. A prominent upper voice often sings syllabically, and melismas are scarce; as in the ottava rima, they are present only at cadenzas. Records survive of the preference for solo performances over polyphonic renditions during the Renaissance. These highlight the interconnection between music and text as well as the central role played by the intelligibility of the text. Baldassarre Castiglione praises the ‘declamation on the viola’ over polyphonic singing not only because we can better understand the melody but because it allows a better recitation of the lyrics:

[…] but as even far more beautiful, to sing to the accompaniment of the viol23, because nearly all the sweetness lies in the solo part, and we note and observe the fine manner and the melody with much greater attention when our ears are not occupied with more than a single voice, and moreover every little fault I more clearly discerned, – which is not the case when several sing together, because each singer helps his neighbour. But above all, singing to the viol by way of recitative seems to me most delightful, which adds to the words a charm and grace that are very admirable.24

Another similarity with the ottava rima is the frottola’s roots in oral tradition. This is particularly evident in the case of the strambotto, the most widespread poetic form of the genre, as used by the improviser Serafino dall’Aquila. In his Apologia, Angelo Colotio describes the way Serafino dall’Aquila performed his strambotti. The description highlights the close relationship between text and music in these improvisations, and the attention Serafino paid to the pronunciation of the words:

They will say that the pronunciation gave him grace; we will confess that in this he surpassed himself. They will say that he spoke in a singular way, but that he tried to match the words to the lute in order to stamp them more deeply on people’s minds, to inflame them and calm them down, as Gracchus adapted his style in the Senate. I say that just as Terpander will always be praised for having added his voice to music and Dardanus to his flute, so Seraphin will always be praised for having given a way to express the passions of love in rhyme, more than anyone else ever before.25

In his essay Qual stile tra’ volgari poeti sia da imitare (What style to imitate among Italian vernacular poets), Calmeta legitimises accompanied monody as a genre of poetry. He invites the reader to imitate

those [poems] accompanied with the instrument, in order to better impress upon not only amorous but also learned hearts. […] Likewise, those who, in singing, put all their effort into expressing the words well when they are of substance, and make the music accompany them in the way that masters are accompanied by servants, are to be held in high esteem.26

Calmeta’s passage clearly illustrates the subordination of music to poetry: poetry, with the help of music, better reaches not only the amorous but also – most importantly – the erudite hearts. It highlights the need to express the words and declaim the text well.

In a letter to Pico della Mirandola, Angelo Poliziano describes a banquet in the Orsini palace.27 During the dinner, Fabio, the son of Paolo Orsini, sings polyphony with friends for the guests. Poliziano points out that the piece was performed from notation; the musicians were reading the music from part books. However, Poliziano is notably more enthusiastic when Fabio sings some verses by Piero dei Medici alone, accompanying himself on a lute:

No sooner were we seated at the table than [Fabio] was ordered to sing, together with some other experts, certain of those songs which are put into writing with those little signs of music [it is difficult to render the sense of contemptuous diffidence conveyed by that ‘quaedam … notata Musicis accentiunculis carmina’], and immediately he filled our ears, or rather our hearts [‘immo vero in praecordia’], with a voice so sweet that (I do not know about the others) as for myself, I was almost transported out of my senses, and was touched beyond doubt by the unspoken feeling of an altogether divine pleasure. He then performed an heroic song which he had himself recently composed in praise of our own Piero dei Medici … his voice was not entirely that of someone reading, nor entirely that of someone singing: both could be heard, and yet neither separated one from the other; it was, in any case, even or modulated, and changed as required by the passage. Now it was varied, now sustained, now exalted and now restrained, now calm and now vehement, now slowing down and now quickening its pace, but always it was precise, always clear and always pleasant; and his gestures were not indifferent or sluggish, but not posturing or affected either […].28

In this account Poliziano explains that Fabio’s voice, singing the monody, was neither that of a reader nor that of a singer; the listener could have perceived it as both, without being able to distinguish whether he was singing or reading. These contemporary testimonies emphasise certain recurring elements: first and foremost, the preference for an accompanied monody rather than a polyphonic rendition, through which the singer could better interpret the meaning of the text; and the extreme flexibility of the sung rendition of the text, in which the sung voice was not easily distinguishable from the spoken voice.

If this is how this monodic repertoire was understood by the contemporaries, we should ask ourselves how this was mirrored in the performance practice of instrumental intabulations of the same music and period. Did the player infer the correct accentuation of the music from an implicit text? If so, a correct understanding of the meter and of poetical conventions would be an essential element for a correct performance of Antico’s arrangements of this vocal repertoire.

Analysis of the Repertoire: Two Examples

In this part, after describing the methodology used, the analysis of two frottolas will be presented in more detail. In order to perform this instrumental repertoire whilst respecting the original vocal model as much as possible, a metrical and semantic analysis of the texts is necessary.

The poetic material can be analysed on the basis of two criteria: first, a metric/prosodic criterium, which defines the subdivision of the verse into metric unities – syllables, feet, stanzas and so on – regardless of the meaning of the text; second, a syntactic/semantic criterium, which divides the text into unities of logically complete meaning.29 These two unities may or may not coincide, although it is often the case in much Italian Renaissance poetry that the two do overlap.

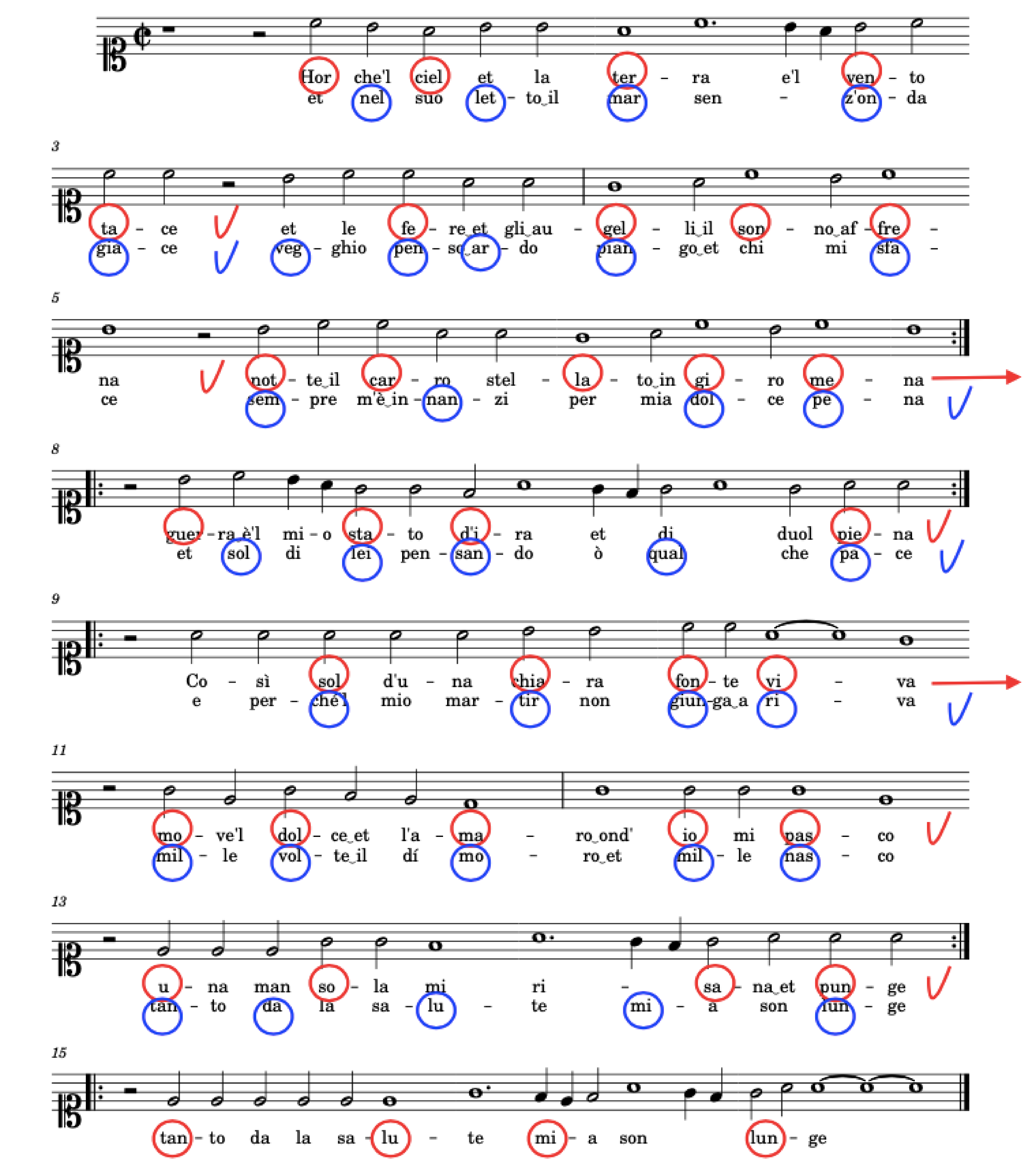

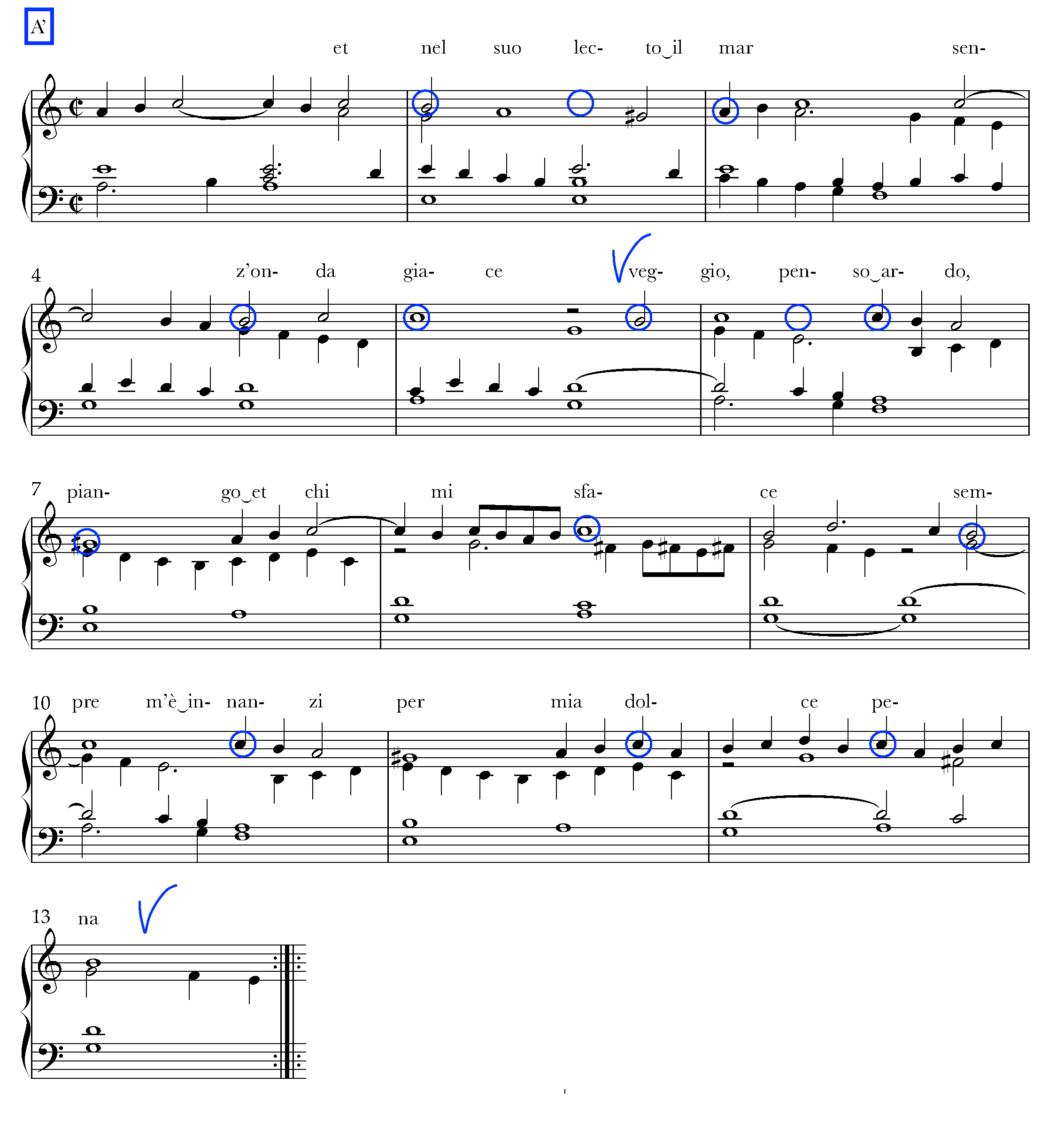

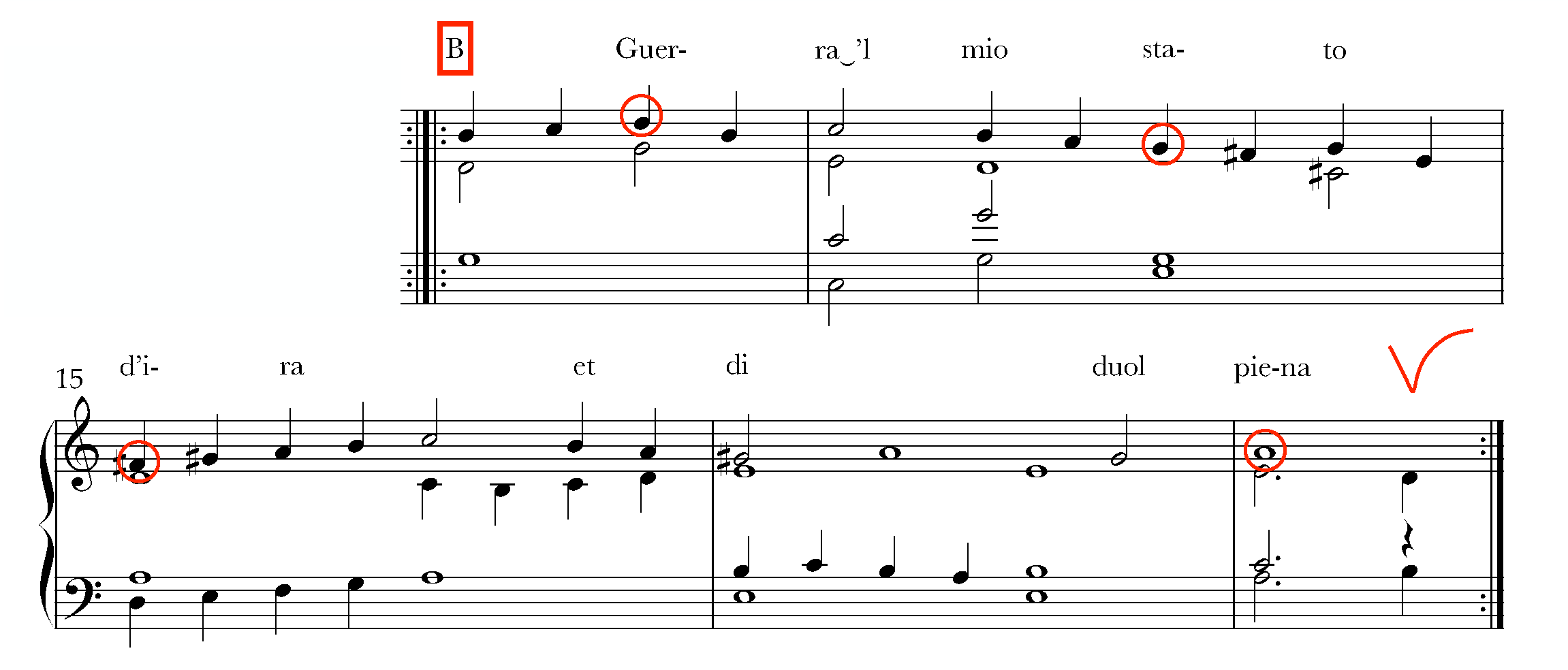

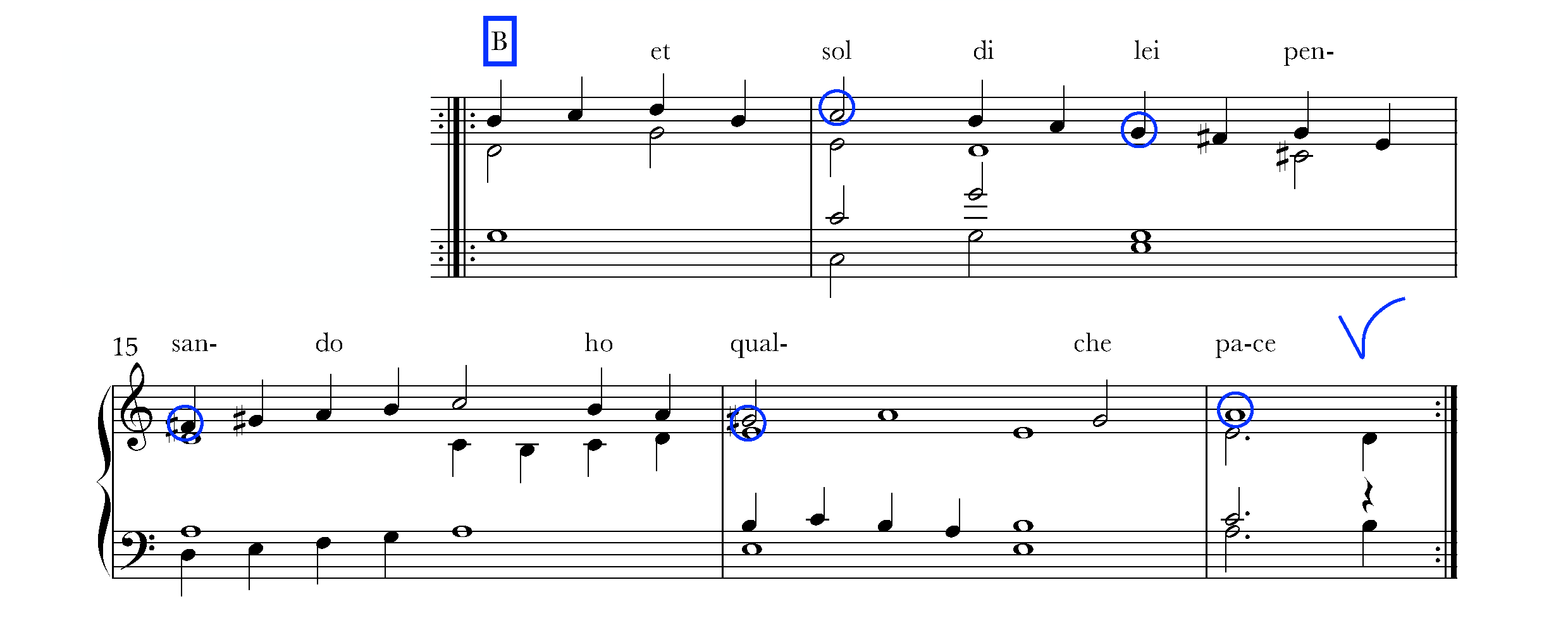

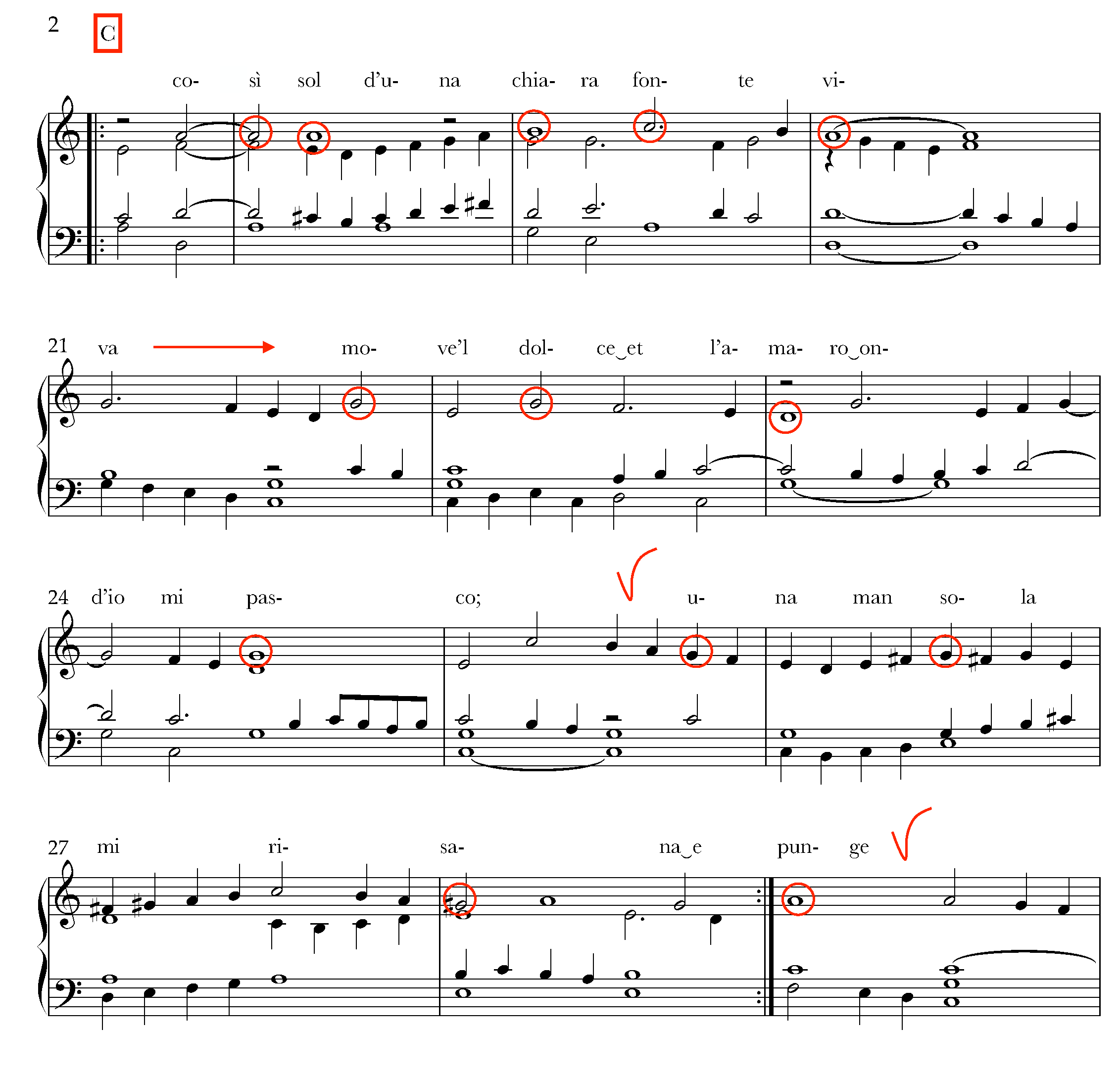

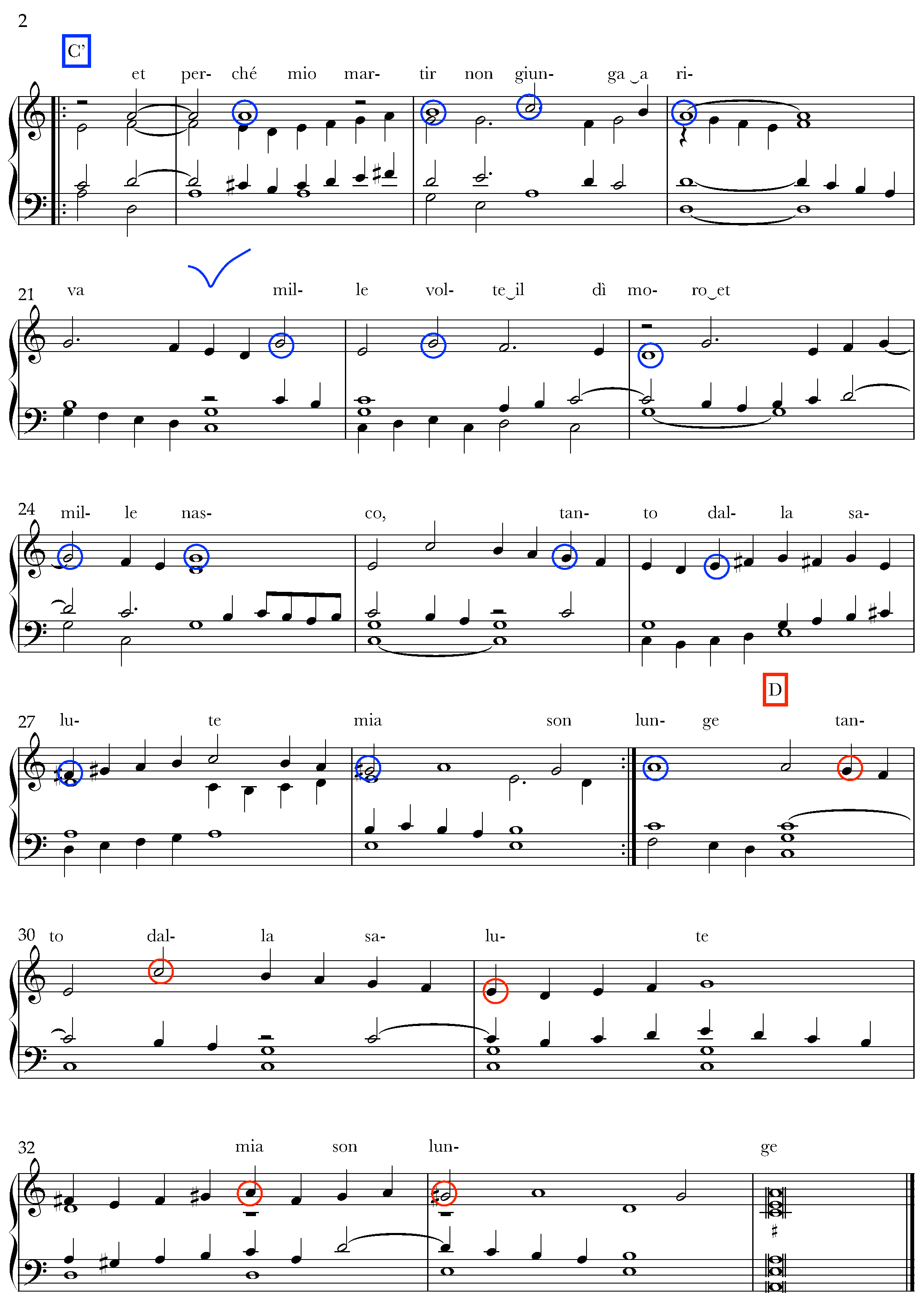

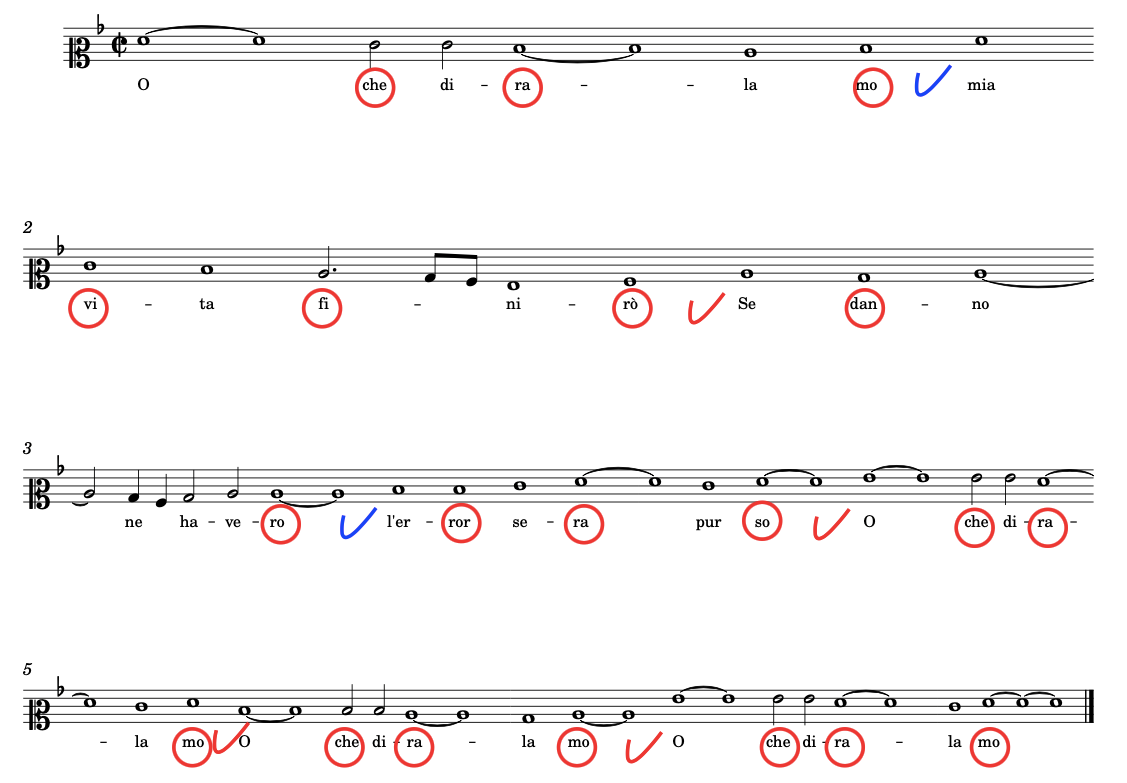

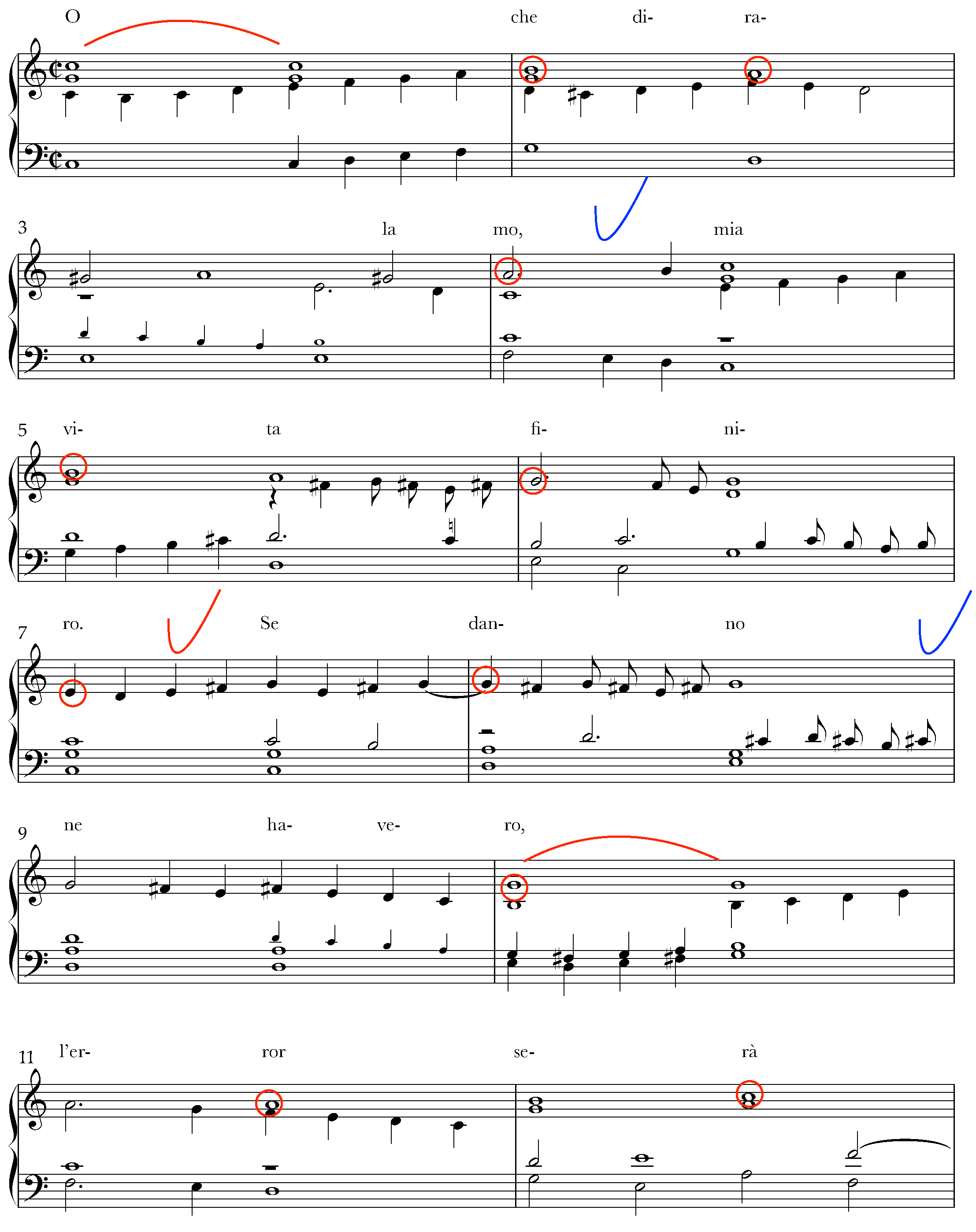

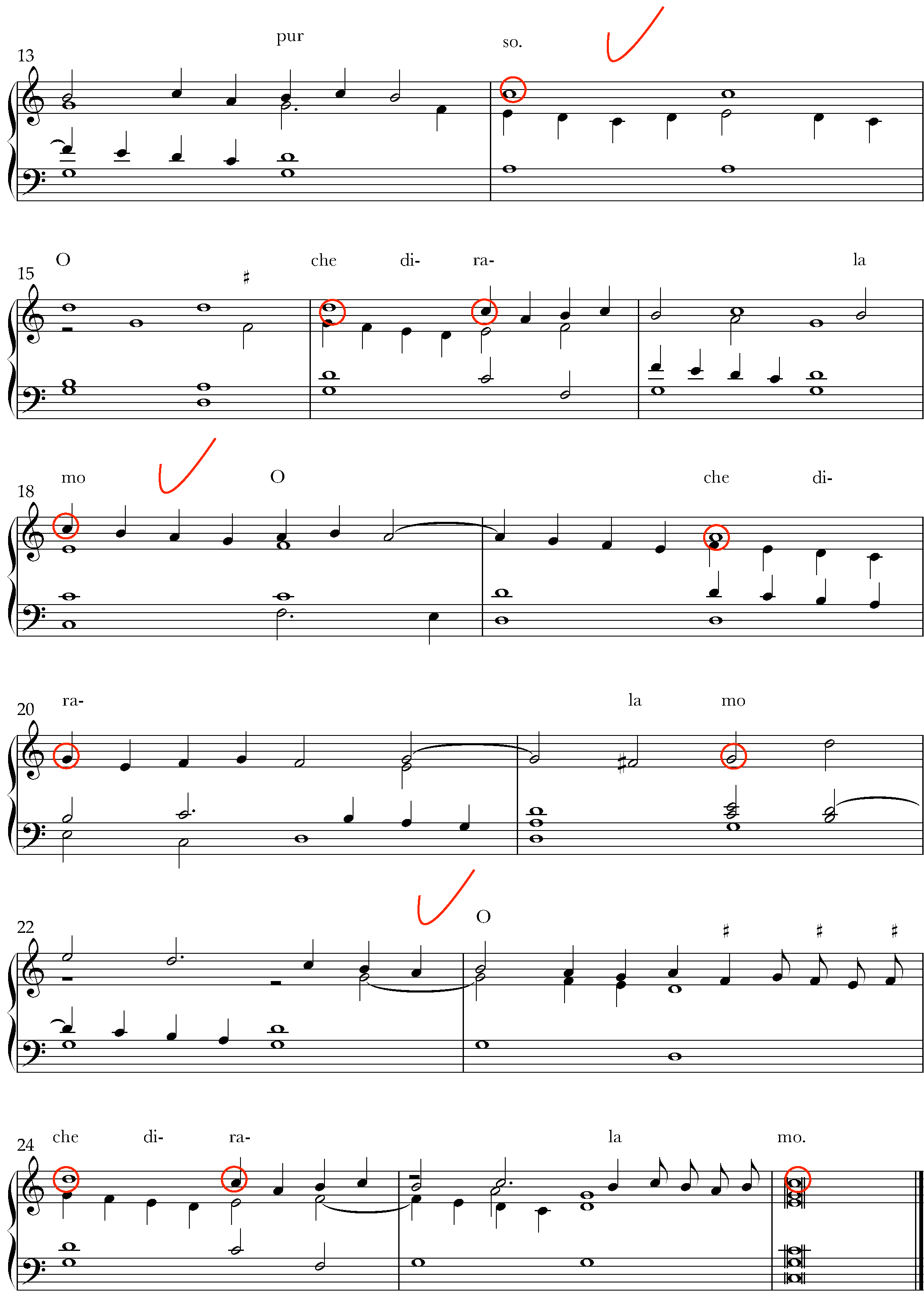

In this study, the lyrics have first been transcribed from the vocal score, trying to respect the correct placement of the text on the keyboard intabulation as much as possible. The lyrics have then been analysed according to the two criteria mentioned above. Tonic syllables of the text are circled directly on the score. The colour red is used for the first text and blue for the repeat if present. On top of the metrical analysis, a set of signs to indicate a semantic analysis is superimposed: for instance, whenever a comma or a breath is needed for the understanding of the text, this has been indicated on the score. Punctuation marking on the lyrics have also been preserved.

The corpus of frottolas can be divided into two groups: those based on endecasillabi and settenari, and those based on ottonari or settenari tronchi. Since endecassilabi and settenari allow for freer accentuation patterns, the combination between music and text is often conflicting and generates unusual patterns, as we saw in the example previously with the two versions of ‘Hor che’l ciel et la terra’. We find several different metric feet in the structure of the verses in these frottolas, such as iambs, trochees, dactyls, resulting at times in a structure close to spoken language. Tonic syllables of the text are placed both on downbeats as well as upbeats of the music. Conversely, we find much clearer accentuation patterns in the second group of frottolas. Here the metrical accents of the verse mainly coincide with the strong accents of the measure, since the ottonario or the settenario tronco is made mostly of iambic feet that gives a very regular rhythm to the verse.

2.1. Hor che’l ciel et la terra

The text comes from Petrarca’s Canzoniere; it is a sonnet built on Italian endecasillabi.

Hor che ’l ciel et la terra e ’l vento tace

et le fere e gli augelli il sonno affrena,

Notte il carro stellato in giro mena

et nel suo letto il mar senz’onda giace,

vegghio, penso, ardo, piango; et chi mi sface

sempre m’è inanzi per mia dolce pena:

guerra è ’l mio stato, d’ira et di duol piena,

et sol di lei pensando ò qualche pace.

Cosí sol d’una chiara fonte viva

move ’l dolce et l’amaro ond’io mi pasco;

una man sola mi risana et punge;

e perché ’l mio martir non giunga a riva,

mille volte il dí moro et mille nasco,

tanto da la salute mia son lunge.

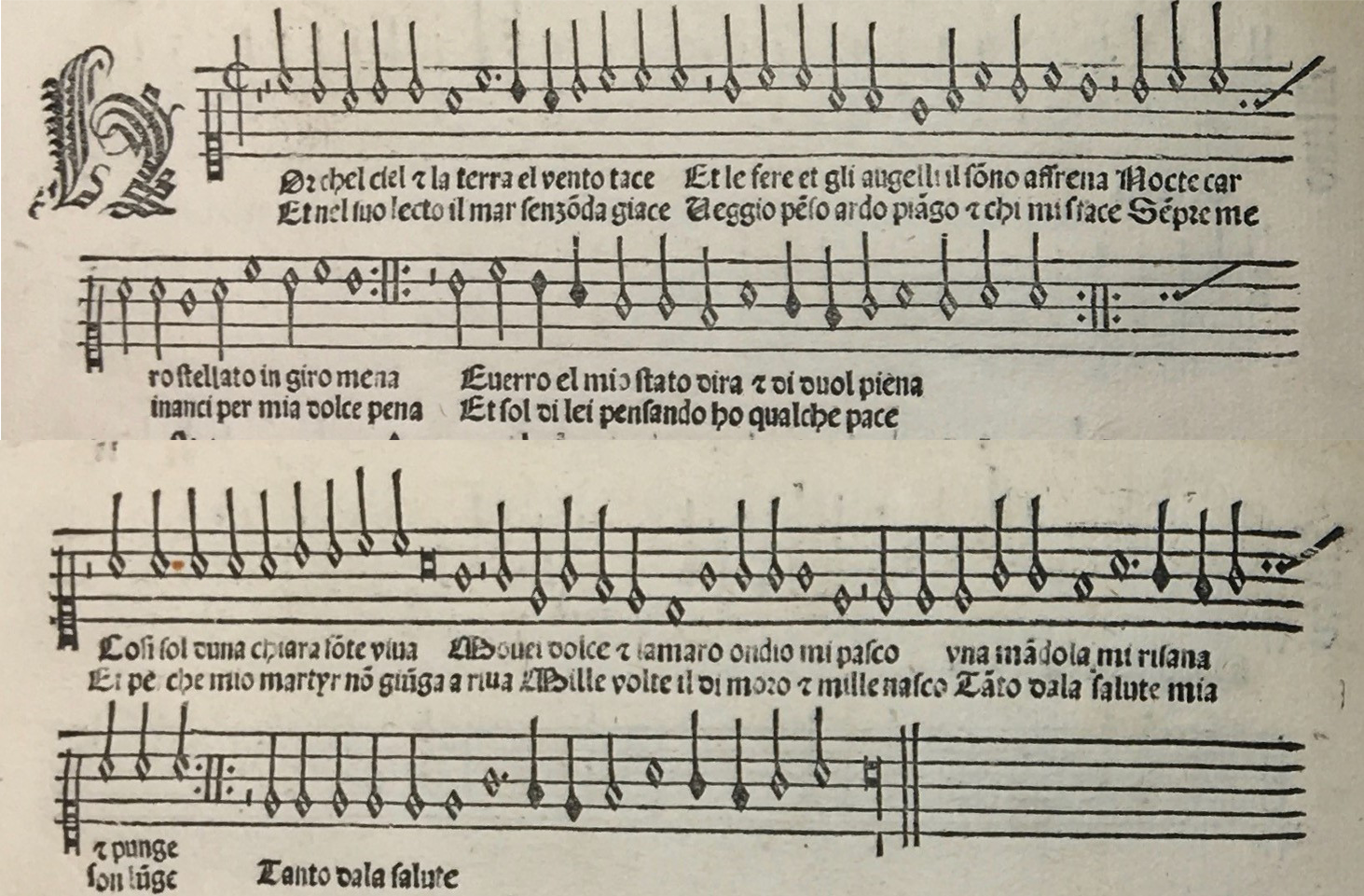

Ex. 6: Bartolomeo Tromboncino, ‘Hor che’l ciel et la terra’, cantus, in: Frottole libro secondo (Rome: Andrea Antico ?, c. 1516) (RISM [c. 1516]10).

Before proceeding to the analysis of the frottola intabulated by Andrea Antico, an analysis of the original frottola is proposed in the following example. Accented metrical syllables have been circled in red and blue depending on whether they refer to the first or second text. Similarly, indications concerning semantic analysis have been marked in red when referring to the first text and in blue when referring to the second.

Ex. 7: Bartolomeo Tromboncino, ‘Hor che’l ciel et la terra’, cantus, in: Frottole libro secondo (Rome: Andrea Antico ?, c. 1516) (RISM [c. 1516]10).

The music follows the structure AA’BB’CC’D, and is based on a common aere, as mentioned above. The piece begins with shifted accents: we have an upbeat on the syllable ‘Hor’, that according to the meter of the verse should be on a downbeat, followed by an accented syllable on ‘che’, which on the contrary should be weak. The second verse of the sonnet starts with an anapest (uu-) with the tonic accent on ‘fe-re’ falling here on the weak beat of the bar.

In the instrumental version (see Ex. 8) the note c2 in the cantus on the syllable ‘fe’ (the word ‘fere’, b. 6) is notated as a single long note, probably from imagining a performance on the organ, whereas in the vocal version the note c2 is syllabically repeated for the two syllables (‘fe’ and ‘re’). In order to underline this accentuated syllable, we would repeat the C, breaking the single long note.

The third verse of the sonnet presents the same structure of the first line: a trochee, a dactyl, and other three trochees (-u,-uu,-u,-u,-u). The first tonic accent on the syllable ‘noc’ (the word ‘nocte’, b. 9) falls here on an upbeat, and the second strong accent of the syllable ‘car’ (the word ‘carro’, b. 10) on a weak beat of the bar. Once again, we have only one long note in the instrumental version. But since the text continues semantically, between A and A’, we should in this case not stop the flow of the cadence.

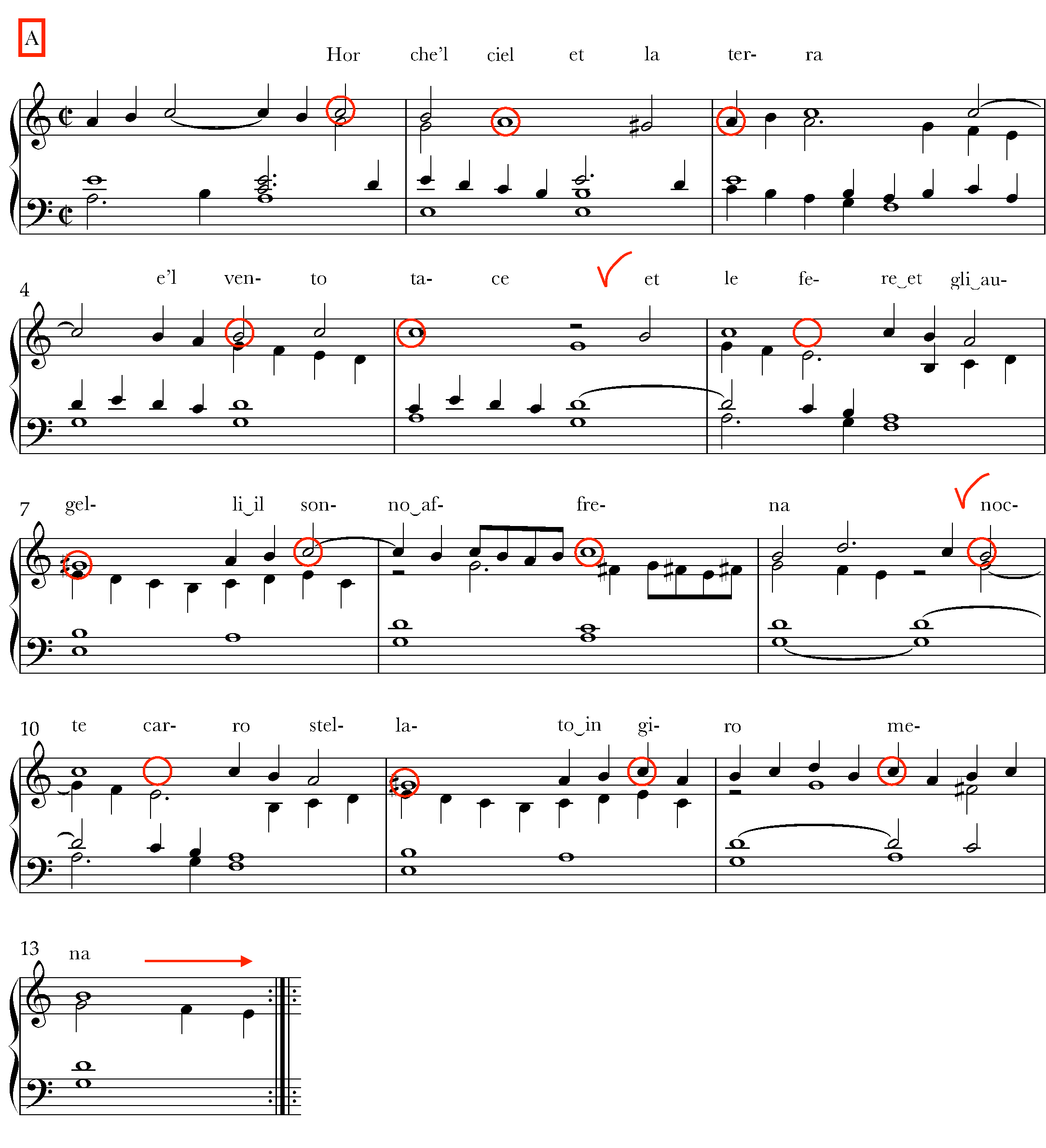

Ex. 8: Andrea Antico, ‘Hor che’l ciel et la terra’, in: Frottole intabulate 1517, mm. 1–13.

In the section A’, the metrical structure is more regular, and the tonic accents of the lyrics generally coincide with the strong beats of the bar. Yet, in the fifth verse of the sonnet the syllable ‘veg’ (the word ‘veggio’, b. 5) falls on an upbeat instead of a downbeat, and later on in the same line, the syllable ‘pen’ (the word ‘penso’, b. 6) is also placed on a weak beat. The same happens in the sixth verse of the sonnet with the syllables ‘sem’ (‘sempre’, b. 9) and ‘pe’ (‘pena’, b. 12).

Ex. 9: Andrea Antico, ‘Hor che’l ciel et la terra’, in: Frottole intabulate 1517, mm. 1–13.

The sections B and B’ contain only one discrepancy between text and music: the tonic accent of the word ‘guer-ra’ falls here on an upbeat rather than the downbeat which is prescribed according with metre of the verse.

Ex. 10: Andrea Antico, ‘Hor che’l ciel et la terra’, in: Frottole intabulate 1517, mm. 13–17.

In section C, music and text are not in agreement in line nine of the sonnet: on the anapest ‘così sol’ (uu-), the accented syllable ‘sol’ (b. 18) falls on a weak beat of the measure instead of a strong one; the same happens in verse ten on the syllables ‘mo’ (‘move’, b. 21) and ‘dol’ (’dolce’, b. 22), and again in line eleven with the syllable ‘man’.

Ex. 11: Andrea Antico, ‘Hor che’l ciel et la terra’, in: Frottole intabulate 1517, mm. 17–28.

Section C’ contains the same accented patterns found in section C, excepting line 14 of the sonnet where the syllable ‘dal’ (‘dalla’, b. 26) falls on a weak part of the measure instead of a strong one. The same happens in section D, in which the last verse of the sonnet is repeated exactly in the same way.

Ex. 12: Andrea Antico, ‘Hor che’l ciel et la terra’, in: Frottole intabulate 1517, mm. 17–34.

The following video contains the author’s version of this frottola. For clarity, the second text has been notated on the lowest staff:

2.2. O che dirala mo

This frottola is made of regular settenari tronchi and uses exclusively iambic feet (u-).

O che dirala mo

Mia vita finiro

Se danno ne havero

L’error sera pur so

O che dirala mo …

Piu non dira così

Amante aspecta el di

Che l giorno e l modo e qui

Che pace trovaro

O che dirala mo …

In the following example, an analysis of the original frottola is proposed. The metrical accents in the text of the first stanza are circled in red. Main caesuras in the text are marked in red, while secondary caesuras are marked in blue (for example to indicate the commas).

Ex. 13: Bartolomeo Tromboncino, ‘O che dirala mo’, cantus, in: Canzoni Sonetti Strambotti et Frottole libro tertio (Rome: Andrea Antico ?, c. 1518) (RISM [15181]).

The accentuation pattern in these lyrics is very clear, with a perfect match between metrical accents and musical accents. But in the instrumental adaptation we find some surprises. From a semantic point of view, the end of a musical sentence consistently overlaps the following one. This is emphasised by the quarter note passages systematically employed by Antico at these semantic caesuras, which makes breathing between semantic periods challenging. Given the regularity of the metrical accentuation, in the following example we show only the analysis of the first stanza. This analysis can also be applied to the other texts.

Ex. 14: Ex. 14: Andrea Antico, ‘O che dirala mo’, in: Frottole intabulate 1517.

Other examples of this group are ‘Per dolor mi bagno il viso’, ‘Animoso mio desire’ and ‘Non più morte ha il mio morire’.

The following video contains the author’s version of the previously analysed frottola:

Conclusions

The frottola was a codified genre in which the text often dictated the structure of the music, since it followed strict literary rules. In vocal repertoire, the metrical structure of the verse, by its own nature, leads the performer to pre-defined accented patterns that (in the specific case of frottolas) are often different from the musical ones. Conflicting accentuation patterns could ideally be solved in a sung performance: a singer can easily stress any tonic syllable, keeping the right accentuation of the verse, and can counterbalance a wrong accentuation with a correct stress in the performance. The singer can articulate the text, stressing tonic syllables and giving weight to the meaning of the text, and can modulate intonation, slowing down or quickening, to again quote Poliziano.30

In the case of the instrumental version of the same repertoire, the same approach would be challenging or could even appear unnatural since no words are present. The literary conventions of the time demand that the instrumentalist rethink the music and opt for what may be some unusual choices. In this article, the author attempts to propose a reading of instrumental repertoire that respects the constraints dictated by the literary conventions underlying the texts of the vocal models.

The solutions in the two frottolas above are practical realisations of what is suggested in this article; many other solutions are possible. Nothing would prevent a performance of these pieces ignoring all literary conventions, just as instrumental pieces on their own. However, if we make the assumption that the audience was familiar with the vocal models, it is fascinating to imagine that our rendition could be close to the practice of the time.

Endnotes

Bibliography

Andrea Antico, Frottole intabulate da sonare organi, libro primo (Rome: Andrea Antico, 1517) (RISM 15173)

Andrea Antico, Frottole intabulate per sonare organi, facs. ed., Bibliotheca Musica Bononiensis IV/42 (Bologna, 1984)

Andrea Antico, Frottole intabulate da sonare organi, 1517: Twenty-Six Keyboard Pieces for Organ, Harpsichord or Clavichord, ed. Christopher Hogwood (Tokyo, 1984)

Andrea Antico, Frottole intabulate da sonare organi (Roma, 1517), ed. Maria Luisa Baldassari (Bologna, 2016)

Apologia di Angelo Colotio nell’opere de Seraphino, al Magnifico Sylvio Piccolhomini S. et benefactore, in: Serafino di Ciminelli, Le rime di Serafino de’ Ciminelli dall’Aquila, vol. 1, ed. Mario Menghini (Bologna, 1894)

Francesco Bausi and Mario Martelli, La metrica italiana. Teoria e storia (Florence, 11993, 2021)

Pietro G. Beltrami, Piccolo dizionario di metrica, (Bologna, 2015)

Francis Biggi, ‘La Fabula di Orpheo d’Ange Politien ou comment rendre une œuvre à l’espace de l’interprétation?’, in: La Musique ancienne entre historiens et musiciens, ed. Rémy Campos and Xavier Bisaro (Geneva, 2014), 491–512

Vincenzo Calmeta, Prose e lettere inedite, ed. Cecil Grayson (Bologna, 1959)

Canzoni novi con alcune scelte di vari libri di canto (Rome: Andrea Antico, 1510) (RISM 15101)

Canzoni Sonetti Strambotti et Frottole libro tertio (Rome: Andrea Antico ?, c. 1518) (RISM [15181])

Baldassare Castiglione, Il libro del Cortegiano, ed. Amedeo Quondam and Nicola Longo (Milan, 2009)

Baldassare Castiglione, The book of the courtier by count Baldesar Castiglione, ed. Leonard Eckstein Opdycke (London, 1901)

Victor Coelho and Keith Polk, Instrumentalists and Renaissance Culture, 1420-1600: Players of Function and Fantasy (Cambridge, 2016)

Alfred Einstein, The Italian Madrigal, 3 vols., trans. Alexander H. Krappe, Roger H. Sessions, and Oliver Strunk (Princeton, 1971)

Gloria Filocamo and Maria Luisa Baldassari, ‘Le “Frottole intabulate da sonare organi” (Roma, Andrea Antico, 1517): testo musicale e contesto sociale della prima intavolatura italiana per tastiera a stampa’, in: Fonti musicali italiane 23 (2018), 7–26

Frottole libro secondo (Rome: Andrea Antico?, c. 1516) (RISM [c. 1516]10)

Frottole libro octavo (Venice: Ottaviano Petrucci, 1507) (RISM 15074)

Everett B. Helm, ‘Heralds of the Italian Madrigal’, in: MQ 27 (1941), 306–18

Stephen D. Kolsky, ‘The Courtier as Critic: Vincenzo Calmeta’s Vita del facondo poeta vulgare Serafino Aquilano’, in: Italica 67 (1990), 161–72

Brunetto Latini, Li livres dou Tresor, publié pour la première fois d’après les manuscrits de la Bibliothèque impériale, de la Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal, et plusieurs manuscrits des départements et de l’étranger, ed. Polycarpe Chabaille (Paris, 1863)

Stefano La Via, Poesia per musica e musica per poesia. Dai trovatori a Paolo Conte, 2nd edition (Rome, 22020)

Francesco Luisi, ‘La frottola nella esecuzione coeva’, in: Il flauto dolce 4 (1974)

Aldo Menichetti, Prima lezione di metrica (Rome/Bari, 2013)

André Pirro, ‘Les “Frottole” et la musique instrumentale’, in: RMl 3 (1922), 3–12

André Pirro and Gustave Reese, ‘Leo X and Music’, in: MQ 21 (1935), 1–16

Nino Pirrotta, Li due Orfei. Da Poliziano a Monteverdi (Turin, 1975)

Nino Pirrotta, Music and Theatre from Poliziano to Monteverdi (Cambridge, 1982)

Nino Pirrotta, ‘Before the Madrigal’, in: JM 12 (1994), 237–52

Dragan Plamenac, ‘The recently discovered complete copy of A. Antico’s Frottole intabulate (1517)’, in: Aspects of medieval and Renaissance music. A birthday offering to Gustave Reese, ed. Jan La Rue (New York, 1966), 683–92

William F. Prizer, ‘Performance practices in the frottola. An introduction to the repertoire of early 16th-century Italian solo secular song with suggestions for the use of instruments on the other lines’, in: EM 3 (1975), 227–35

William F. Prizer, ‘The frottola and the unwritten tradition’, in: Studi musicali 15 (1986), 3–37; repr. in: Secular Renaissance Music. Forms and Functions, ed. Sean Gallagher (Farnham, 2013), 181–215

Francesco Saggio, ‘Improvvisazione e scrittura nel tardo-quattrocento cortese: lo strambotto al tempo di Leonardo Giustinian e Serafino Aquilano’, in: Cantar ottave. Per una storia culturale dell’intonazione cantata in ottava rima, ed. Maurizio Agamennone (Lucca, 2017), 25–45