Towards Ideals of Perception and Performance in Sixteenth-Century Keyboard Music

Catalina Vicens

How to cite

How to cite

Abstract

Abstract

The study of 16th-century keyboard music, integral to historical performance since the early music revival of the late 20th century, has traditionally focused on structural analysis from notated sources and inferred improvisation practices. A paucity of historical performance sources has left many performance aspects unaddressed, relying heavily on aesthetics established by earlier generations. This article takes a transdisciplinary approach to examine Renaissance keyboard music, unravelling the complex interplay of elements in harpsichord playing, encompassing tangible and intangible factors. It aims to bridge the gap between contemporary aesthetics and the historical context, shedding light on the ideals shaping musical perception and performance.

Exploring George of Trebizond’s rhetorical treatise De suavitate dicendi, and its emphasis in the importance of sweetness in rhetoric, the article parallels ideals of speech delivery with the art of harpsichord playing. It introduces a novel method to integrate non-musical historical sources into performance practice, applying rhetorical principles to analyse 16th-century keyboard musical taste, including tempo, rhythm, embellishments, timbral variety, technical aspects, material culture, and the composition-performance relationship. Addressing how to translate theory into guidance for modern performers, the methodology offers a structured framework for studying and performing 16th-century keyboard music, not presenting empirical results but fostering a alternative approach to better understand and convey the era’s musical ideals.

About the Author

About the Author

Catalina Vicens performs globally as a soloist on antique keyboards encompassing harpsichords, organs, and pianos, and is considered one of the leading experts on medieval and Renaissance keyboards. Directing the Tagliavini Collection of historical keyboards at San Colombano Museum in Bologna, she passionately promotes these musical treasures. Her role as a researcher and harpsichord teacher extends worldwide, with posts at the Royal Conservatory of Brussels, Oberlin Conservatory, delivering masterclasses at renowned centres such as the Curtis Institute, the Juilliard School and UdK Berlin. She imparts her expertise as a jury member at esteemed competitions, notably the International Harpsichord Competition in Bruges, and her lectures resonate in museums and universities across the globe.

Outline

Outline

Background

Since the beginning of the early music movement, Renaissance keyboard music has attracted performers and audiences. At the turn of the mid-20th century, pioneering recordings like those of Ralph Kirkpatrick with his 16th Century Harpsichord Music by Cabecon, Byrd, Gibbons, Bull, Sweelinck set the tone for a new era of historical keyboard music recordings. It was soon followed by national keyboard music anthologies such as Claude Jean Chiasson’s French Harpsichord Masters released in 1951, the organ recitals by Flor Peeters, Old English Masters, and Old Italian Masters released in 1953 and 1954 respectively and Thurston Dart’s series, Masters Of Early English Keyboard Music, recorded on the clavichord, harpsichord, and organ. By the 60s, while 18th-century music overtook the recording output produced by the developing early music movement, LPs like Gustav Leonhardt’s Englische Virginalisten recorded on a harpsichord by Johannes Ruckers (Antwerpen 1640), Giuseppe Zanaboni Bolognese’s anthology performed on the historical organs of San Petronio in Bologna (1475 and 1594), and Hubert Schoonbroodt’s Lublin Tablature’s Dances on the organ of the Basilica of Our Lady in Maastricht (1652) showed with mastery the potential of incorporating the use of antique historical keyboards into the historical performance practice discourse. In the 70s, artists like Elisabeth Chojnacka and János Sebestyén continued to unveil Polish and Hungarian Renaissance keyboard music while fostering new music for the instrument, and personalities like Colin Tilney as well as Christopher Hogwood, Trevor Pinnock, and Ton Koopman reminded their audience about the music of the virginalists while becoming pivotal figures in baroque music.

On the other hand, over the last half-century, Renaissance Studies has become one of the most diverse and developed fields in modern-day academia, and historical musicologists devoted to studying 16th-century sources, compositional practices, musical culture, and organology have produced an impressive output. Nevertheless, proponents of historically informed performance practice have chosen to include only a reduced scope of scholarly research and have stayed mostly impermeable to other fields of study. In this regard, we cannot underestimate the weight of the pioneering generation of 20th-century harpsichordists and organists, and that which followed, in the way we listen to and perform 16th-century keyboard music today. It is also pertinent to be reminded of how the sonic image of Renaissance keyboard music has been shaped by the implied notion that it is a repertoire that precedes, leads to, and culminates in the artistic climax of the great baroque keyboard works. Consequently, it has often been coloured by the search for achieving contrast to what is understood as a point of arrival and resulting in aesthetic decisions driven by the attempt to define that which is opposed to the baroque rather than describing what truly constitutes the Renaissance keyboard music ideal itself.

Perspectives

The revived interest in the performance of 16th-century keyboard music on the harpsichord has developed significantly over the last decade. It has catalysed the need to find spaces for sharing information and perspectives, of which the first symposium on ‘Universum rei harmonicae concentum absolvunt: the Harpsichord in the 16th century’ organized by Augusta Campagne and Markus Grassl, held in April 2021 at The University of Music and Performing Arts Vienna, is a worthy example.

While baroque and classical repertoires have been at the core of the development of educational programs on historical performance practice in many European countries and across the world, 16th-century keyboard music performance has not yet been institutionalized. This offers a new set of possibilities that can be derived from a critical evaluation of the methodologies used in the teaching of baroque performance practice and a rethinking of the modes of knowledge transmission established in the last half-century. Engaging in such a process at this point of Renaissance keyboard music performance practice may help to avoid the patterns that have prevented ongoing research to dialogue with performance, and have served to establish modern ‘schools’ of historical performance rather than fostering a critical understanding of historical musical and artistic concepts.

A renewed attitude can foment the musician’s ability and curiosity by not limiting the reading of sources (often using fragmentary information) to establish exclusive performance truths, and that instead supports and encourages the continuous critical reading of diverse source types, including the wealth of research on medieval and Renaissance intellectual culture allowing to access the 16th century from a chronological perspective.1 Just as importantly, it finally would grant the space required for acknowledging the elements of theoretical and practical research that are not quantifiable but fundamental to the musical process, which can result in a conscious and critical engagement in the process of translation and embodiment.

Score vs Source: Re-Identifying the Blanks

Aesthetic understanding is only possible within

a culture through the contextual references to

the forms of life. To describe an ensemble of

aesthetic rules means to describe a specific culture.2

Performers dealing with any repertoire conceived in the distant past, are subject to fill in information left out of the musical page. From the multiple parameters that constitute a performance, those that cannot fit on a table of rules are certainly complex to treat and intimidating to address consciously and systematically. To confront them, identifying those blank spaces is the first step.

How does the performance of instrumental polyphonic music change depending on the sound source? How do we listen to the instrument, its registers, its tuning, its consonances and dissonances, and how do we make sense of them when performing a structured musical thought? How does the instrument’s nature affect an improvisation based on a historical compositional style? How did musical migration shape the composers’ and performers’ discourse and how does that affect our idea of style and ornamentation? Why would we strike the keys in one way or the other on different instruments and what are we aiming to achieve with each approach to touch? What is a specific keyboard technique, such as the use of fingering patterns, useful for, and what does it really imply, allow, prevent and look for? What are we trying to achieve when adding diminution and ornamentation to a pre-existing compositional model, and how do we understand and affect the original model in the process? How do we translate text and vocal music into the keyboard and what do we search by doing so? How do we hear the voice that sings and declaims? How do we imagine the 16th-century listener?

Musical understanding cannot be reduced to the mechanical application of explicit rules: the expressive game of musical rules obeys a tradition that is mostly implicit, which determines the choices.3

Many of these questions cannot be fully or even partially answered by looking at what we often understand as musical sources (mainly derived from musical notation or performance indications documented in historical treatises). In this article, I introduce an alternative methodology that can contribute to answering them by providing information that is explicitly open to different readings. Herewith I intend to lay out a way to address the complexity embedded in the study of 16th-century keyboard music and to encourage performers and educators to move toward a more holistic understanding of the music of the past.

While this type of approach to the work with sources gives space for a variety of modern performance outputs, I chose here to focus on what, I argue, is a key concept in Renaissance keyboard music and which can shape each of the questions above and certainly many more. Drawing from writings on rhetoric, aesthetics, and material culture, I explore a term that might seem trivial to the modern ear, but that can contribute to understanding the ideals which drove artists, writers, musicians, performers, and listeners alike: ‘sweetness’.

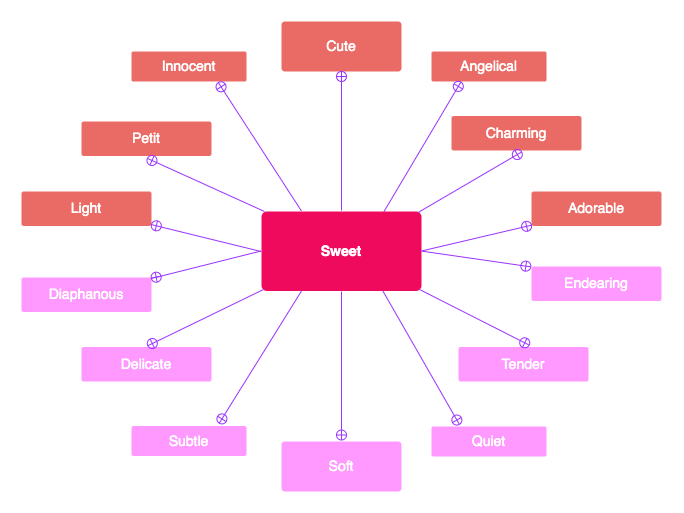

A Matter of Taste

The most evident way of understanding this term is in its use to describe a quality perceived by our gustatory and olfactory system as a basic taste.4 When applied to describe the quality of something outside of what can be identified by the sensory system as containing sugars, in its modern connotation it refers to something pleasant with the quality of something soft, charming, cute, delicate, diaphanous, light, airy, petit, subtle, tender, quiet, innocent, angelical, endearing and adorable (Fig. 1).5

During the late 15th and 16th centuries, the word ‘sweetness’ was used with particular frequency in written documentation that included the description of musical performance and the perception of sound quality. The ideal of a dolcezza mirabile was embedded in Baldassare Castiglione’s account of the solo performer,6 and Pietro Bembo’s description of Isabella d’Este’s singing with dolcezza e suavità.7 The marchioness of Mantua was a key figure in the development of Italian music culture during the turn of the 16th century, establishing aesthetic parameters that would be imitated and developed across the peninsula and beyond. Turning her court into an archetype of the transdisciplinary humanistic environment, she acted as a catalyser between arts and sciences, where music would be permeable to the various intellectual and aesthetic ideals in circulation.

Fig. 1: Semantic network of ‘sweet’ according to the English language. Image: Catalina Vicens.

One of the closest composers to Isabella, Marchetto Cara (1465–1525), is widely represented in the first Italian keyboard music print, the Frottole intabulate da sonare organi published by Andrea Antico in 1517. As described by Castiglione, Cara was able to move the listener, ‘by a delectable way and bursting with feeble sweetness, he tenderizes and penetrates souls, imprinting in them sweetly a delightful passion’.8 While the style of the author often uses literary oxymorons, here it does so to convey a complex picture of the performer-listener’s active and passive sensory experience, where intense sweetness has the piercing ability to move and stir passions. An image familiar to those keyboardists, whose instruments’ mottos and inner-lid paintings reminded them that the act of keyboard playing was beyond a mechanic reproduction of music.9

It is one of the first accounts that describe the sound of the harpsichord, half a century earlier, that also underlines its characteristical sweetness. ‘The harpsichord is an instrument of marvellous sweetness for making polyphonic music. It has metal strings in all its courses […] it’s percussive like the clavichord, except that it sounds sweeter and more sonorous’,10 writes Paulus Paulirinus in Liber viginti artium, finished c. 1463. In the description of musical instruments in this encyclopaedic work, it’s possible to identify qualities from the descriptions themselves but also from the comparison between instruments, which could challenge modern connotations (where for example the clavichord, the lute, and the harp are not described as sweet).11 Nevertheless, when ‘sweetness’ is read in Renaissance sources through a modern lens, it tends to lead to assumptions or even conflicting images.12

Suavis / suavitas and dulcis / dulcedo, dulcor, can be translated as ‘sweet’ and ‘sweetness’ in English, but are etymologically distinctive. They ‘are, however, from the earliest extant Latin literature down to late pagan and Christian Latin, broadly synonymous, being both used to express gustatory as well as other sensuous, emotional, and mental pleasures.’13 In the arts, this term has been applied throughout the centuries to denote the experience of something that represents ‘good taste’. When good taste is perceived in a contemporary context, defining it proves to be challenging but often unnecessary, as it is tacitly understood by the interactions between the agent and its environment. Therefore, for defining and describing the experience of something perceived as ‘tasteful’ in a moment of a distant past, what was considered a pleasurable or a desired artistic experience, we need to define the environment, or the agent and its context.

In order to engage with this complex task, I propose a transdisciplinary approach that uses the methodology of actor-network-theory to provide concrete elements that can guide the reading of musical sources and their application in performance.14 This comprehends building a network of historical references, in this case around the connotations and associations of the term ‘sweetness’, which, analysed from a performative perspective will add clarity about the historical musical agent in the interaction with its environment. In this process, the outcome will be the generation of new questions which will leave space for modern performers to search for an answer to them with an individual conscious approach, filling in the gaps of those blank spaces, while allowing for the network indicators, and therefore the questions, to keep expanding.

The Sound of Sweetness

Amor che ne la mente mi ragiona’

cominciò elli allor sì dolcemente

che la dolcezza ancor dentro mi suona.15

– Dante Alighieri, La Divina Commedia

(Love that converses with me in my mind,

he then began, so sweetly

that the sweetness sounds within me still.)

With these lines of the Divina Commedia and as a forerunner of the Renaissance, Dante pins down the definition of a new style. The sweet one. The Dolce Stil Novo puts sweetness at the forefront of literature, with a taste that goes beyond being a mere aesthetic quality, but intrinsic to a new rhetorical style. Sweetness is to be desired, is to be lived by, and is to be performed.

Dante draws from the biblical tradition, recalling in this passage psalm 118: ‘how sweet are your words to my taste, sweeter than honey to my mouth!’,16 where a close connection is established between taste and knowledge. Sweetness becomes not only a sensorial perception but a religious-infused moral act, where the sound of divine knowledge penetrates the heart through devoted listening. According to Artistotle, ‘the sense of touch is conducted by the flesh, and the taste by the tongue. Unlike cerebral senses vision, hearing, and smell, all of which operate out of the brain, touch and taste are both connected directly to the heart.’17 Augustine, one of the most influential authorities during the early modern period, acknowledges in his writings that suavitas is a desirable rhetorical quality, but he warns that it must be used only to flavour the ‘wholesome’ or ‘nutritious’ substance of truth or wisdom; if used to add appeal to evil or falsehood, it offers merely a ‘pernicious sweetness’. Eric Jager observes that suavitas and related words overlap in form and meaning with another family of terms that include suasio (persuasion) and suadere (to persuade). All the terms spring from the same Indo-European etymon meaning ‘sweet’.18

During the classic revival taking place in Italy during the 15th and early 16th centuries, other authors of antiquity are revised, and sweetness is incorporated into the arts as a way to convey meaning. A tasteful transmission of knowledge, through rhetoric and its application to the other arts, will lead to a pleasurable and balanced experience of sweetness.

Crafting Sweetness: Rhetoric in Trebizond’s De suavitate dicendi

In the early 15th century George of Trebizond dealt with sweetness as one of the most effective rhetorical tools. The Greek rhetorician embodies the synthesis of different traditions characteristic of the Renaissance, mixing the ideas of several figures from Antiquity, including the rhetorical writings by Aristotle, Cicero, and Demosthenes. He also analyses the seven styles of Hermogenes, whose discussion of rhetorical sweetness had not yet been explored in Western Europe.

In Trebizond’s treatise De suavitate dicendi, dedicated to Girolamo Bragadin, he introduces Byzantine rhetoric to the Latin West, writing about how to become the perfect orator through the ‘sweetness of speech’.19 According to Trebizond, sweetness is a particularly important element of performance as it will make the message persuasive not only by creating intellectual pleasure in the listeners but by pleasing synchronically all the senses. Therefore, since suavitas creates an emotional impact on the audience, the information can be absorbed easily and quickly.20

Defining the links and constitutive elements of form and figure of speech, Trebizond creates a cloud of components and qualities that result in the sweetness of speech. One of them is artificium, which is the way and the manner in which a thought is explained in words, where ‘all the embellishments, which many people call “figures of thought”, are to be considered here. [artificium] is encompassed by an artistic rhythm that is once confined and free.’21 Thus, the rhetoric command is achieved by the way or manner in which ideas are explained and embellished, and in how their rhythmical flow is structured. It also relies on the qualities of clarity, sincerity, and appropriateness (gravitas), elements that can be related to the composition (ideas, form, and genre) and their delivery (mode, swiftness, and character).

The author also points out that one of the chief means of creating sweetness is variatio: ‘variety seems to have the largest utility and sweetness not only for painters, poets, or actors but also in any field where it is appropriate, especially in the arena of the orator.’22 Alluding to Cicero, he sustains that variation is achieved by the variety in the tones of the voice (sonority, precision, force, and pointedness), the appropriate use of thoughts and approach to the thoughts, as well as the use of styles (in the rhythmical organization of figures, clauses, and cadences). Imitation is also an essential part of the rhetorical discourse. It does not rely on copying the models, the work of the greatest masters, but taking them as models and adapting them and variating them depending on the discourse. With the right combination of all the elements of sweetness, the orator will achieve eloquence and accomplish victory.

In the following diagram, the different elements described in Trebizond’s De suavitate dicendi are organized through nodes and points linked by directed edges or arrows. They leave the space for creating new network links within the system that can expand the significance of different relationships between elements of rhetoric.

Fig. 2 Sweetness definition network after Trebizond’s De suavitate dicendi. Image: Catalina Vicens.

The elements of Trebizond’s rhetoric can also be applied to composition and performance, as the role of the orator can be mirrored and translated into the musical domain as that of the composer/performer. Thus, while Trebizond is only one of the rhetorical models that were highly influential in the Italian peninsula and the rest of Europe during the Renaissance, the application of rhetorical sweetness into the study of early 16th-century keyboard music can provide keys to the understanding of 16th-century harpsichords, their music, and their performance.

From this diagram we can extract questions such as the following ones:

-

What does a free and confined rhythm balance mean, how can it be applied to the overall musical structure and metrical structure, and according to which parameters does the performer alternate or fluctuate between them?

-

If embellishments, as figures of thought, are meant to convey meaning, how do musical embellishments documented in 16th-century keyboard sources add significance to the musical message? How do written-out diminutions, graces, and embellished musical gestures change the rhythm of the discourse? How does the knowledge of their function within the musical discourse give us information about how and why to add embellishments where they are not written and shape our understanding of style?

-

How could the importance of timbric variety change our understanding of the aesthetic of 16th-century instrument building itself? Do certain qualities of antique Renaissance keyboard types resonate with principles of sonic variety described in Trebizond?

-

What are the technical means to create variety in the harpsichord’s sonority? Can control and variation of force in the performer’s touch help to give structure and flow to the composition?

-

How can the familiarity with other closely related instruments, such as fretted Renaissance clavichords, 16th-century organs, and Renaissance plucked instruments inform about the variety of sound within a sound source’s identity?

-

What does it mean to variate in precision? Is it referred to the precision of chords (alternation between arpeggiation and synchronic chords), to the interpretation of rhythm and meter, or another performative parameter? How does this differ from variating the level of pointedness in the performance? Does this instead relate to the degrees of incisiveness of touch or rhythm as well?

-

How do the variations in composition taken from a model tell us about the discourse (and its function) intended by the composer or arranger?

-

How does variation in the use of a variety of modes and genera (diatonic, chromatic, and enharmonic) in a polyphonic composition develop from the search for rhetorical suavitas, and how does it influence the delivery of the musical thoughts?

-

If imitation is not copying, how does the performance of vocal intabulation at the keyboard imitate the model and variate it?

-

Which elements of the score allow choosing the mode, swiftness, and character of the piece?

-

What does it mean to perform gravitas (with sincerity, clarity, and appropriateness) today? How does the changing of performative context change all the technical elements in order to deliver a ‘speech’ appropriate to the listener?

Exploring the ideals of perception and performance in 16th-century harpsichord music through other disciplines of Renaissance studies, such as Trebizond’s elements of rhetoric, it’s possible to unveil and redefine the components that form the implicit rules for the delivery of musical meaning. Doing it so from a chronological perspective, and embracing alternative methodologies for the teaching and learning of Renaissance keyboard music, can help to pose the essential performance questions that are often left untackled.

While we cannot quantify the changes in our own performance when setting an aesthetic and/or environmental goal, taking such path for the re-reading of historical sources containing information such as compositional styles, ornamentation, keyboard technique, fingering patterns, musical and grammatical text analysis, etc., will allow for a ‘translation’ with a more complex and refined de-codification system.

This approach leaves room to embrace serving as a performer of today while being translators and mediators of an art of the past,23 grappling the fact that a performance is not deducible from the sum total of causal factors, and allowing a process of accumulating knowledge to shape musical communication. Thus, I argue, a historically informed/inspired musical embodiment process may begin.

Endnotes

Bibliography

Willi Apel, Geschichte der Orgel- und Klaviermusik bis 1700 (Kassel, 1967)

Eliot Bates, ‘Actor-Network Theory and Organology’, in: JAMIS 44 (2019), 41–51

John Bryan, ‘“Verie Sweete and Artificiall”: Lorenzo Costa and the Earliest Viols’, in: EM 36 (2008), 3–18

Mary Carruthers, ‘Sweetness’, in: Speculum 81 (2006), 999–1013

Baldassarre Castiglione, Opere del conte Baldessar Castiglione Il cortegiano, vol. 1 (Florence, 1854)

Paulo Chagas, ‘Musical Understanding: Wittgenstein, Ethics, and Aesthetics’, in: Music, Analysis, Experience: New Perspectives in Musical Semiotics, ed. Costantino Maeder and Mark Reybrouck (Leuven, 2015), 115–33

Antoine Hennion and Stephen Muecke, ‘From ANT to Pragmatism: A Journey with Bruno Latour at the CSI’, in: New Literary History 47 (2016), 289–308

Stanley Howell, ‘Paulus Paulirinus of Prague on Musical Instruments’, in: JAMIS 5–6 (1979), 9–36

Eric Jager, The Tempter’s Voice: Language and the Fall in Medieval Literature (Ithaca, 1993)

Abdool-Hack Mamoojee, ‘“Suavis” and “Dulcis”: A Study of Ciceronian Usage’, in: Phoenix 35 (1981), 220–36

John Monfasani, George of Trebizond: A Biography and a Study of His Rhetoric and Logic (Leiden, 1976)

Lucia Calboli Montefusco, ‘George of Trebizond’s “De suavitate dicendi”’, in: The Classics in the Medieval and Renaissance Classroom: The Role of Ancient Texts in the Arts Curriculum as Revealed by Surviving Manuscripts and Early Printed Books, ed. Juanita Feros Ruys, John O. Ward, and Melanie Heyworth (Turnhout 2013), 267–85

Claude V. Palisca, Music and Ideas in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries, curated by Thomas J. Mathiesen (Champaign, Illinois, 2006)

Paulus de Praga dictus Paulirinus, Liber viginti artium (c. 1463), PL-Kj Codex 257

Benjamin Piekut, ‘Actor-Networks in Music History: Clarifications and Critiques’, in: Twentieth-Century Music 11 (2014), 191–215

Heidelinde Pollerus, Tasteninstrumente als kunsthistorische Objekte. Cembalo, Clavichord, Spinett, Virginal. ‘Meine Seele hört im Sehen’ (Graz/Vienna, 2018)

The Princeton Dante Project (2.0), <https://dante.princeton.edu/>

Alexander Silbiger (ed.), Keyboard Music Before 1700 (New York/London, 2004)