Or How Metal Musicians Sustained a Dialogue of Community with Their Fans in a Period of Moral Panic about Heavy Metal Music

Andy R. Brown

Zitieren

Zitieren

Brown, Andy R. 2025. »Songs in the Key of Depression, Suicide and Death: Or How Metal Musicians Sustained a Dialogue of Community with Their Fans in a Period of Moral Panic about Heavy Metal Music«. In Musik und Suizidalität. Interdisziplinäre Perspektiven, hg. von Julia Heimerdinger, Hannah Riedl und Thomas Stegemann. Wien und Bielefeld: mdwPress.

Abstract

Abstract

This paper takes a fresh look at the 1980s moral panic against heavy metal music, which was blamed by US elites for a spike in teen suicide rates, and contrasts it with a »failed« panic in which the mostly (middle class) female fans of the EMO genre were able to successfully contest their stigmatization as a »suicide cult« by the UK right-wing tabloid Daily Mail in 2008. Drawing on contemporary moral panic theory, this study revises the view that the mostly »blue collar« fans who became the victims of the US panic lacked a collective voice of resistance. It reexamines the hitherto unacknowledged prevalence of thrash metal »suicide note« songs, such as Metallica’s »Fade To Black«, which promoted a dialogic conversation between metal bands and their fans that enabled them to »live through« economically difficult and politically distorted times.

Introduction

With the partial exception of »Suicide Solution« (Ozzy Osbourne 1980), a song about drinking yourself into an early grave, none of the songs cited in the US Senate hearing (19 September 1985) on the »Labelling of Rock Music«, and in legal proceedings thereafter, concerned with linking the popularity of heavy metal with an increase in youth suicide rates, are actually about suicide. This did not prevent Republican party affiliated groups, such as the Parents Music Resource Center (the PMRC; the so-called »Washington wives«, see below), aided by a phalanx of academic »experts«, from conveying the opposite impression, often via the deployment of sensationalist tactics aimed at the media and the wider public. Indeed, this period can be characterized as one in which several professional groups, including teachers, lawyers, social workers, psychiatrists, and academic psychologists, claimed and sought (or simply assumed) evidence of a »causal« link between the popularity of heavy metal music with »blue-collar« youth and an alarming rise in suicide rates in North America. Osbourne’s song, for example, was twice cited in separate legal indictments linking it to male youth suicides, while Judas Priest’s cover of Spooky Tooth’s »Better by You, Better than Me« (1978) was claimed, in what one would have to describe as a »show trial«, held in Reno, Nevada, from 6 July to 24 August 1990, to carry a »backmasked« message (»Do it, do it«) that drove two young men to act out a suicide pact. After the »not guilty« verdict, the band’s lead singer, Rob Halford, was quoted in Billboard as saying:

It tore us up emotionally hearing someone say to the judge […] that this is a band that creates music that kills young people […] We accept that some people don’t like heavy metal, but we can’t let them convince us that it’s negative and destructive. Heavy metal is a friend that gives people great pleasure and enjoyment and helps them through hard times. (Quoted in Bessman 1990, 46 and 52)

Despite the political rhetoric, pseudo-science and ideological attacks that dominate this extraordinary period of politically sanctioned moral panic, and seemingly at odds with the mission statement of metal scholars Deena Weinstein (1991) and Robert Walser (1993) to defend the genre from these unwarranted and seemingly baseless accusations, I want to argue that heavy metal music in this period did feature a number of songs that address mental illness, depression and suicide, including, for example, Metallica’s »Fade to Black« (1984) and »Welcome Home (Sanitarium)« (1986), Megadeth’s »In My Darkest Hour« (1988), and »A Tout le Monde« (1994), and Suicidal Tendencies’ »Institutionalized« and »Suicidal Failure« (both 1983). But discovering the existence of these songs — one of which is mentioned in the US Senate hearing, as I will show — does not retrospectively prove the case of the political elite. Rather, the existence of such songs should be viewed as evidence of a musical commentary on the dire economic situation that the majority of working-class youth were facing and trying to live through. For example, the band Suicidal Tendencies, both in their name and in their music and lyrics, offers a satirical, confused and often angry first-person narrator commentary on the plight of the troubled characters depicted in their songs and the situations they find themselves in.

In the first part of my paper, I focus on moral panic theory and its recent revision and critique by contemporary scholars, focussing on the phenomenon of a failed moral panic. I do so by drawing on a case study of the attempt by the UK right-wing newspaper, the Daily Mail, to stigmatize the newly popular genre of emo (shorthand for »emotional hardcore«) as a »suicide cult« encouraging its fans to self-abuse and suicide so that they can join The Black Parade,1 the title of the 2006 album by the band My Chemical Romance (MCR), who are at the centre of the controversy. But the attempted panic is not sustained, mainly because of the impact of collective youth protests, online and in the streets, of its majority female fans, denouncing the rhetoric of the mid-market tabloid paper. I then go on to compare this failed moral panic with a successful one staged against heavy metal, involving a show trial of metal musicians and elite political proceedings, leading to the labelling of heavy metal albums as requiring »parental guidance« (see below) because of their content and leading to many of their majority blue-collar male fans being sectioned in psychiatric institutions and subject to »de-metaling« programs (Rosenbaum and Prinsky 1991).

In the second part of my paper, I focus on the songs themselves, including Metallica’s »Fade to Black« and »Welcome Home (Sanitarium)«, and the MTV videos by Megadeth and Suicidal Tendencies, such as »A Tout le Monde« and »Institutionalized«, in order to clearly demonstrate that there were songs about suicide in the period of moral panic about heavy metal and its negative impact on youth. I then take this further in suggesting that, particularly within the genre of thrash metal (see Brown 2025) — a genre not generally associated with narratives of despair and inner turmoil, even by metal scholars — there is clear evidence of a song type that is especially concerned with these themes, particularly suicide. Not only this but many of these songs, perhaps surprisingly, take the form musically of a ballad that is concerned with a troubled »interior« narrative about depression, suicidal thoughts and death, or offer, in effect, a »suicide note« (or a set of notes on suicide, such as failed attempts, etc.) to the listener. My analysis seeks to explore what is musically and lyrically distinctive about the »thrash metal ballad« as a suicide note in order to place its emergence within a wider context — one characterized, I will argue, by a dialogic conversation between metal musicians and metal fans (conducted through music and songs) that is concerned with addressing the experience of trying to »live through« this difficult economic and politically distorted period and, in the process, is able to cohere a shared sense of community, collective identity and empathy.

The origins of this paper derive from critical reflection on two previous studies, »Suicide Solutions?« (Brown 2011b; 2013) and »The Ballad of Heavy Metal« (Brown 2016), where I sought not only to revise the findings of each but to draw them together in a re-examination of the role of heavy metal music in moral panics about youth suicide, particularly with respect to thrash metal songs contemplating or announcing an act of suicide.2 If there was a key tipping point in this re-examination, it was the »recognition« — first noted by Pillsbury (2006) regarding Metallica — of the thrash metal ballad as a recurrent feature in band repertoires, that allowed a dark and melancholic first-person narrative concerned with depression, suicidal thoughts and the contemplation of death. But this aspect, seemingly hidden in plain sight, not only connected thrash to the controversial role of the sentimental »power ballad« in heavy metal’s chart success in the 1980s, but also allowed a further reclamation to be had in noting the widespread existence of the dark and contemplative ballad in the classic heavy metal music of the 1970s, such as Judas Priest’s »Beyond the Realms of Death« from the Stained Class album (1978) — the track (along with »Heroes End«) that was first indicted in the 1990 civil action brought against the band by the family of the teenager Jay Vance (who, along with his friend Ray Belknap, had allegedly entered into a »suicide pact« after listening to it). But the other key element involved in the rethinking of the role of the ballad in heavy metal music was the discovery, made possible by reading back over the US Senate hearing documents, that the thrash metal ballad »Fade to Black« by Metallica was also presented by »expert witnesses« as evidence of songs inviting teenage suicide, despite the fact that the song was misnamed »Faith in Black« (U.S. Congress. Senate 1985, 14).

Part One

Moral Panic Theory

The opening paragraph of Stanley Cohen’s classic text Folk Devils3 and Moral Panics from 1972, states:

Societies appear to be subject, every now and then, to periods of moral panic. (1) A condition, episode, person or group of persons emerges to become defined as a threat to societal values and interests; (2) its nature is presented in a stylized and stereotypical fashion by the mass media; (3) the moral barricades are manned by editors, bishops, politicians and other right-thinking people; (4) socially accredited experts pronounce their diagnoses and solutions; (5) ways of coping are evolved or (more often) resorted to; (6) the condition then disappears, submerges or deteriorates and becomes more visible. Sometimes the object of the panic is quite novel and at other times it is something which has been in existence long enough, but suddenly appears in the limelight. Sometimes the panic passes over and is forgotten, except in folklore and collective memory; at other times it has more serious and long-lasting repercussions and might produce such changes as those in legal and social policy or even in the way the society conceives of itself. (Cohen quoted in Critcher 2003, 9)

Thus, moral panics are cyclical »spasms« that occur in advanced industrial societies with mass media. The numbers (added by Critcher) indicate that there are six stages to a typical cycle, although Cohen resists the idea that the model is sequential or overly determined, since each stage may enable or constrain progression to the next. Nevertheless, the model indicates a key relationship between primary (professionals, accredited experts) and secondary definers (media, politicians) identifying a »social problem«. Deviant youth groups are labelled and »stigmatized« — via exaggeration, distortion and symbolization (symbolic stereotypical characteristics) in news reporting cycles, leading to calls for social control/new laws, strategies and »measures« — to stamp out »evil« or »moral decay«, etc. Moral panics typically succeed because the »knowledge/info« gap between actual groups and parents that constitute the »mainstream« is wide. Youth groups exist before reporting, but the effect of reporting is to confer and confirm deviance and delinquency upon them.

Critics of Cohen’s Moral Panic Theory

Ulf Boëthius (1995) argues that moral panics over youth and media have become less easy to sustain because of the explosion in new media and popular cultural forms, a greater pluralism of moral and cultural values, a decline in social and political tensions between classes and a greater heterogeneity in the social composition of national populations and lifestyles. Angela McRobbie (1994) and McRobbie and Sarah L. Thornton (2000) consistently emphasize three areas that they believe date the model: (1) that it operates with an excessively monolithic view of the separation between elites, the media, experts and the control culture, on the one hand, and hapless deviants on the other; (2) that youth culture is itself increasingly dependent upon and integrated into forms of media which communicate its values, perspectives and interests; (3) that mass media forms are successful to the extent that they misrepresent the nature of folk devils and social problems to a gullible and dependent audience, when contemporary media audiences are far from this, being both intelligent and active in a changed media environment that encourages their interactivity. De Young argues that although the framework is useful, it cannot account for folk devils fighting back, divided public opinion and ambiguous resolutions that are »more symbolic than real« (de Young 1998, 272). While Ungar (2001) argues that accumulated knowledge about moral panics is suspect because it is based on the retrospective study of successful rather than unsuccessful or failed examples.

Chas Critcher’s timely »makeover« of moral panic theory suggests that »[t]he folk devil is more likely to be recruited from groups who cannot speak for themselves and have nobody to speak for them« (Critcher 2003, 145). But if putative folk devils have the means to contest their demonization or find that there are a range of alternative forms of media that can do it for them, then the assertion seems undermined. Or does the idea of »empowered folk devils« depend on the social status and cultural resources of the stigmatized group itself? (de Young 1998, 275). It was this counter-thesis I sought to test in my study, »Suicide Solutions? Or, How the Emo Class of 2008 Were Able to Contest Their Media Demonization, Whereas the Headbangers, Burnouts or ›Children of Zoso‹ Generation Were Not« (Brown 2011b; 2013).

»Suicide Solutions?« Revisited

My comparative case study, »Suicide Solutions?« (Brown 2011b; 2013), offered analysis of two press-mediated morality scares, concerned with the influence of metal (and metal-related) music genres on incidences of teen suicide in two different periods. I characterize the attack on heavy metal as a »successful« moral panic and on emo as an »unsuccessful« one. Both panics have teen suicide cases at their centre and the claim that it was their metal or emo music fandom that led them to this. The origin of the term »Suicide Solutions« is a section subheading in Robert Walser’s »Can I Play with Madness« chapter (Walser 2014, 145),4 to which I added the question mark to allow a contrast between the heavy metal and emo scares as offering a possible suicide solution for troubled teens. The subheadings, particularly that of the »children of ZoSo« (which references the »Led Zeppelin IV« album),5 refers to the subcultural term used by Donna Gaines in her investigative study of the teenage »burnouts« at the centre of one of several moral panics about music and suicide in 1980s North America, Teenage Wasteland (Gaines 1998, 179—81) (see below).

Based on this comparison, I argued that the campaign against heavy metal during the 1984—19916 period in the United States was an example of a successful moral panic, whereas the attempt to generate a similar scare about emo in the UK in 2008 was an example of a failed one. So why did one succeed and the other not? First, while sensationalist press coverage on behalf of »parents« characterized both panics, in the UK example, this lacked endorsement by elite/professional bodies, so societal »solutions« were never clearly posed. Second, the enhanced role of niche/subcultural media, especially online, in contesting the emo panic, played a central role, particularly in enhancing the ability of emo fans to »speak back« to their demonizers, exemplified by the march by emo fans on the offices of the mid-market newspaper the Daily Mail, which was widely reported by the broadsheet press.7 Finally, to the extent that emo is a middle-class defined subculture with a pronounced female profile, it was not viewed as a threat to societal norms in quite the same way as that of the masculinist, blue-collar-defined fandom of 1980s heavy metal (Brown 2011b, 19). All of which appeared to confirm Chas Critcher’s view (cited above). However, while this revised study will broadly agree with this assertion, it seeks to identify and uncover the hitherto unrecognized role that heavy metal and hardcore bands played in supporting their »politically« stigmatized and »socially« alienated fans via their songs and subcultural stance against what is retrospectively viewed as »oppressive« and »excessive« institutional power.

A Brief Overview of the »Unsuccessful« Emo Panic

Here is an outline of the first phase of the media coverage of the UK emo panic (Brown 2011b, 29):

-

Tragic Emo Teenager Uses Tie to Hang Herself. Evening Standard (London), 7 May 2008.

-

Popular Schoolgirl Dies in ›Emo Suicide Cult‹. The Daily Telegraph, 7 May 2008.

-

Girl, 13, Hanged Herself after Becoming Obsessed with ›Emo‹. The Times, 8 May 2008.

-

Suicide of Hannah, 13, the Secret Emo. The Sun, 8 May 2008.

-

Girl Hanged Herself to Impress Emo Cult. The Daily Telegraph, 8 May 2008.

-

20th SUICIDE IN BRIDGEND. Daily Mirror, 8 May 2008.

-

Suicide of Girl, 13, Hooked by Cult That Glamorizes Death. Daily Mail, 8 May 2008.

-

Hannah Was a Happy 13-Year-Old until She Became an ›Emo‹ — Part of a Sinister Teenage Craze That Romanticises Death. Daily Mail, 15 May 2008.

-

Why No Child Is Safe from the Sinister Cult of Emo. Daily Mail, 16 May 2008.

Here is the second phase of the coverage (Brown 2011b, 30):

-

Maligned Emo Fans to March on Daily Mail. The Guardian, 22 May 2008.

-

Reasons to Be Cheerful. The Independent, 23 May 2008.

-

EMO: Welcome to the Black Parade. The Independent, 23 May 2008.

-

Mail’s Chemical Reaction. The Observer, 25 May 2008.

-

The Kids Who March in the Black Parade. The Times, 30 May 2008.

-

Black Parade of Teen Angst. Irish Independent, 31 May 2008.

-

Is Emo a Suicide Cult? The Guardian, 31 May 2008.

-

Emo Fans Protest at ›Suicide Cult‹ Label. The Observer, 1 June 2008.

-

SUICIDE Newspaper under Siege as Fans of Emo Music Protest at ›Suicide Cult‹ Coverage of Teenager’s Death. Independent on Sunday, 1 June 2008.

What is remarkable about the second phase of the emo panic is that it is entirely unexplainable within the classic framework. The event that coheres the coverage and acts as its object and rationale is the march on the offices of the Daily Mail of »200« emo fans protesting their depiction as a suicide cult and defending the music of emo bands, such as My Chemical Romance (see fig. 1). What is also noteworthy about the coverage is that it is almost entirely made up of broadsheet titles covering a story of popular criticism of moral panic type reporting, particularly in the Daily Mail but also in the tabloid press more generally. This coverage also reveals that at least half of the items report the planning and announcement of the march before it happens, thereby acknowledging the existence of alternative, internet-based »viral media« as the source of the anti-Mail campaign.

And as for the teen »folk devils« predicted by the panic model, the marchers on the Mail are far from inarticulate. For example, Anni Smith, the 16-year-old organizer of the protest, claimed the Mail coverage was: »badly researched journalism in danger of promoting irresponsible stereotyping« (quoted in The Independent, 23 May 2008). So unexpected was this news event and its publicly articulated criticism that the Mail was compelled to release a statement defending itself (reported in The Guardian, 2 June 2008):

The Daily Mail’s coverage of the ›Emo‹ movement has been balanced, restrained and above all, in the public interest. Genuine concerns were raised at the inquest earlier this month on 13-year-old Emo follower Hannah Bond who had been self-harming and then tragically killed herself. […] In common with other newspapers we ran an accurate news story recording the coroner’s remarks and the parents’ comments. We also published two other articles, one of which explained the background to the Hannah tragedy in calm and un-sensational language. The other was a first person opinion piece by a well-known writer, written from the perspective of a mother concerned for her children. We have also run two prominent page lead letters from an Emo music fan and from a fan of My Chemical Romance defending their point of view. […] Since this protest was announced a great deal of misinformation has appeared on the internet, much of which confuses what the Daily Mail has actually published with the comments of web site readers and blogs over which we have no control and which have stirred up emotions. (Emphasis in original)

In their statement of defence, the Mail describes its coverage as balanced, objective and in the »public interest«, contrasting this with the online activism of the MCR fans, which it accuses of »stirring up emotions« and spreading »disinformation«. The irony here is that successful moral panic discourse works through a process of exaggeration and distortion, made possible by different newspaper titles competing, rather than seeking to question the coverage and even defend the putative folk devils being stigmatized, as was the case with the »attempted« emo panic story.

Figure 1: This phrase is a quote from MCR band leader Gerard Way, reacting to the Mail coverage onstage at Reading festival. Photo: Jenny Matthews/Alamy.

»Successful« Moral Panic8

Now we turn to the headbangers, burnouts or »children of ZoSo«: the folk devils at the centre of the USA panic (Brown 2011b). In the period from 1984 to 1991, the genre of heavy metal and the youth culture identified with it were subject to a sustained campaign of elite condemnation and mass-mediated moral panic that was unprecedented even by the standards of the troubled history of the reception of popular teenage music fads and fashions in North America (Chastagner 1999; Weinstein 2000, 265—70; Walser 2014, 137—51). The initiators of the campaign were an organization that called itself the Parents Music Resource Center (PMRC), largely »composed of Washington D.C. wives and mothers« (Martin and Segrave 1993, 292), such as Susan Baker and Tipper Gore. The PMRC charged that rock music had become sexually explicit, morally depraved and pornographic. They produced a list of offending songs (known as »the Filthy Fifteen«),9 the majority of which were by heavy metal bands, and called for a ratings system that would control access to such music by minors. The campaign, which typically focused on quoting »explicit« lyrics and »objectionable« album covers from the PMRC’s »bad list« (ibid., 293—94), received widespread coverage in national media, such as Newsweek, the Washington Post, The Phil Donahue Show, CBS Morning News and Today.

Following a presentation on the »evils of rock music« by the PMRC to the Justice Department’s Commission on Pornography, the Senate Committee initiated proceedings into »porn rock« and record labelling, held on 19 September 1985. There, several accredited »expert« witnesses claimed a causal connection between »epidemic« rates of male suicides and heavy metal songs:

Some rock artists actually seem to encourage teen suicide. Ozzie Osbourne sings »Suicide Solution.« Blue Oyster Cult sings »Don’t Fear the Reaper.« AC/DC sings »Shoot to Thrill.« Just last week in Centerpoint, a small Texas town, a young man took his life while listening to the music of AC/DC. He was not the first. […]

This is Steve Boucher. Steve died while listening to AC/DC’s »Shoot to Thrill.« Steve fired his father’s gun into his mouth. A few days ago I was speaking in San Antonio. The day before I arrived, they buried a young high school student. This young man had taken his tape deck to the football field. He hung himself while listening to AC/DC’s »Shoot to Thrill.« Suicide has become epidemic in our country among teenagers. Some 6,000 will take their lives this year. Many of these young people find encouragement from some rock stars who present death as a positive, almost attractive alternative. […]

Ozzie Osbourne on his first solo album, shown here, sings a song called »Suicide Solution.« Ozzie insists that he in no way encourages suicidal behavior in young people, and yet he appears in photographs such as these in periodicals that are geared toward the young teenage audience. For those of you who cannot make that out because of the lights, it is a picture of Ozzie with a gun barrel stuck into his mouth. (U.S. Congress. Senate 1985, 12—14).

In October 1985, Osbourne was sued by a 19-year-old youth’s parents, who claimed that their son was listening to the artist’s record the night he took his own life. In the summer of 1990, the band Judas Priest was taken to court by the parents of two boys who acted out a suicide pact, allegedly at the behest of »subliminal (or backward) messages« placed on the album, Stained Class (1978). Such claims reflected widespread fears among religious organizations, such as Parents Against Subliminal Seduction (PASS), over the impact of Satanism and satanic symbols on impressionable youth (for example, Raschke 1990, 171; Richardson 1991).

But a legal obstacle the detractors had, which became apparent in the attempt to indict the musicians Ozzy Osbourne and Judas Priest, citing the lyrical themes of »Suicide Solution« and »Beyond the Realms of Death«, was the First Amendment, which defends the right of US citizens to express an opinion, artistic, political or otherwise. This allowed the legal defence of the bands to say that such claims would not be accepted in a court of law. This is why the two attempts to indict Ozzy Osbourne were not successful and why the prosecuting attorneys went for Judas Priest as the »subliminal criminals« in the Jay Vance and Ray Belknap »backmasking« trial rather than citing lyrics from the ballad »Beyond the Realms of Death«, since a subliminal message could be viewed as unconscious (»supraliminal speech«) and therefore not covered by the First Amendment (Brown 2011b, 26).

All of this »expert testimony« has been critiqued by Deena Weinstein (2000, 250—57) and Robert Walser (1993) as musically and politically suspect. What is also apparent in the cited extracts is that the claims lack a causal link and rely on the repeating of what have come to be known as »magic correlations«, that is, confusing correlation with causation. A notable example among many that followed is a study that links the youth suicide rate in fifty US states with the subscription rate of heavy metal magazines (Stack et al. 1994). Despite this lack of causal evidence, the flurry of youth cultural panics about metal and hardcore punk music and its detrimental impact on American youth did result in more than »symbolic« outcomes, such as the »Parental Advisory« label.10 This was especially the case with panics about youth suicide cases viewed as a direct result of listening to heavy metal music, which is pointedly documented in Donna Gaines’ ethnographic study, Teenage Wasteland (Gaines 1998).

Gaines’ book opens with a double suicide pact: two teenage girls and two boys gas themselves in a car in a garage in the blue-collar suburb of Bergenfield, New Jersey, in March 1987, while allegedly listening to heavy metal on the car stereo.11 They and their friends are described by Gaines as »kids who listened to thrash metal, had shaggy haircuts, wore lots of black and leather. […] Teenage suburban rockers whose lives revolved around their favorite bands« (ibid., 3). Gaines, a sociologist, social worker and journalist, was commissioned by The Village Voice to investigate the story behind the suicide. She had previously worked as a »street counsellor« for troubled adolescents on Long Island, New York — and, more importantly, as she later revealed, had grown up amidst a teen drugs-and-music youth culture nearly 20 years earlier, and had seen friends become addicts, end up in detoxification centres or meet early deaths (Frymer 2006). Despite her academic credentials, Gaines brought a degree of empathy to her investigation and importantly a knowledge of heavy metal and hardcore music. In fact, it was the recognition of her »Ace of Spades« Motörhead lapel button that persuaded the first group she approached to begin to open up and confide in her about their feelings and the situation they faced as »burnouts«, in the upper poor (blue-collar) suburb of Bergenfield (Gaines 1998, 58).

Working-class families moved to Bergenfield in the late 1950s and 1960s because of rising incomes, reasonable housing costs and an expanding school system. But by the 1980s, deindustrialization had decisively impacted the US economy, resulting in a decline in skilled and technical industry jobs, educational opportunities and employment prospects, which impacted blue-collar youth the most. As Ryan Moore describes it:

The jobs awaiting them after graduation were more likely to be in services and retail, where social skills and personal appearance are of paramount importance, thus putting metalheads, especially the self-described ›dirtbags‹, at a disadvantage. With their opportunities for mobility restricted to military service or the [pipedream] of rock stardom, these young metalheads looked to their future like »animals before an earthquake«12. (Moore 2010, 82)

As a largely redundant population of declining economic value, the metalheads that Gaines observed were often being shuffled between institutions and diagnosed with various psychological and behavioural conditions. Some were warehoused at a place called »the Rock« (in Rockleigh), a special education facility that housed those who had been diagnosed as »emotionally disturbed« (Gaines 1998, 119). While in the 1980s, federal funds for social services had become increasingly scarce, the new politically sanctioned and funded special education sector was expanding, not least because well-intended service providers were labelling troubled teens as »emotionally disturbed« to get funding for them. There was also an extraordinary growth in rehabilitation institutions and private mental hospitals for teenagers, diagnosed with conduct disorder (CD) and oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) (Moore 2010, 82). This is confirmed by the number of young people confined in psychiatric wards, which rose from 16 735 in 1980 to over 36 000 in 1986 (Males 1996, 248). In effect, the private psychiatric hospitals capitalized on the parental climate of fear by including CD and ODD in mental health treatment, with the typical 30-day detention diagnosis stay bringing in around $16 000 in insurance money, leading Mike Males to wryly rename the problem »Kid-with-Insurance-Disorder« (ibid., 243—53). Both Gaines and Moore provide examples from interviews with teens who were persuaded by their parents to check into a local institution for psychiatric testing and then found themselves detained for 30 days because of their age (being under 18) (Moore 2010, 83; Gaines 1998, 127).

A particular noted example of a special facility for the rehabilitation of youth who had allegedly become the victims of drug use, suicidal thoughts and satanic worship through their fandom of heavy metal and punk was the Orange County, California, based Back in Control Training Center, which was founded on the principle that metal was a cult and metal fans needed to be deprogrammed (Lewis 1986). According to Rosenbaum and Prinsky (1991), in one jurisdiction in California, a list entitled »Rules to Depunk or Demetal« had been circulated to probation officers. According to this list, taken from the Back in Control Center’s Punk Rock and Heavy Metal Handbook (Pettinichio 1986), minors are ordered:

-

Not to dress in any style that represents Punk Rock or Heavy Metal.

-

Not to wear hair (dye or cut) in any style that represents Punk Rock or Heavy Metal.

-

Not to associate with known Punk Rockers or Heavy Metalers.

-

Not to wear any Punk Rock or Heavy Metal accessories — earrings, or jewelry, spikes or studs.

-

Not to frequent any place where Punk Rock or Heavy Metal is main interest.

-

Not to listen to Punk Rock or Heavy Metal music.

-

Not to write or draw Punk Rock or Heavy Metal.

-

Not to tattoo, cut, harm or injure self in any way.

-

To keep parents informed of whereabouts at all times. (Rosenbaum and Prinsky 1991, 531)

Rosenbaum and Prinsky further add that these rules had been attached by probation officers to the last three »blank« categories of the court rules of probation (ibid.).

In summary, the campaign by the PMRC against heavy metal music and its fans during the period of its greatest popularity (1984—1991) is an example of a successful moral panic, which demonized a section of blue-collar youth as »folk devils«. This had consequences for many of them, from having to live with negative stereotypes of themselves (burnouts, dirtbags, etc.) to being sectioned in psychiatric units and/or processed as delinquents via »de-metaling« programs (Brown 2011a).

Part Two

Revising the Study: The Thrash Suicide Ballad

The album I am holding up in front of you is by the band Metalica [sic!]. It is on Electra Asylum records. A song on this album is called »Faith in Black.« It says the following. »I have lost the will to live. Simply nothing more to give. There is nothing more for me. I need the end to set me free.« »Death greets me warm. I will just say good-bye.« (U.S. Congress. Senate 1985, 14)

This is a quote from the US Senate hearing (missed by Weinstein, Walser and other scholars) concerning the »well-known« thrash metal ballad »Faith in Black« by Metallica. The song, from the Ride the Lightning album (1984), is entitled »Fade to Black« not »Faith in Black«, the correct title surely more indicative of a contemplative suicide song. Although Metallica’s lead singer/guitarist and lyricist, James Hetfield, has said the song was written about the depression he felt after the band had all their guitars and equipment stolen on the eve of a European tour, the lyrics convey a distinct sense of despair and inner turmoil that support the accusation made in the hearing that it is in effect a »suicide note«.

For Pillsbury, the song offers »an inward-looking psychological journey in which the narrator describes his decision to commit suicide« (Pillsbury 2006, 41). Pillsbury goes on to name the song cycle it initiated Metallica’s »Fade to Black« paradigm13 and, interestingly, compares it to the 1980s power ballad. However, the lyrical theme of most power ballads — the ups and downs of romantic love — has no place in the song cycle, although the presence of a »less-aggressive male interiority […] goes some way toward linking the two« (ibid., 54). Indeed, the »presentation of interiority« is viewed as the »primary aesthetic characteristic« of this song cycle (ibid., 55). As I have already noted, there are other songs in the thrash genre that deal with this subject matter, such as Megadeth’s »In My Darkest Hour« (1988) and »A Tout Le Monde« (1994). It would therefore be more appropriate to name the song type the thrash metal suicide ballad: slow or mid-tempo songs that are concerned with a troubled »interior« contemplation on mortality or, in effect, a »suicide note« contemplating a future death or past failed attempts.

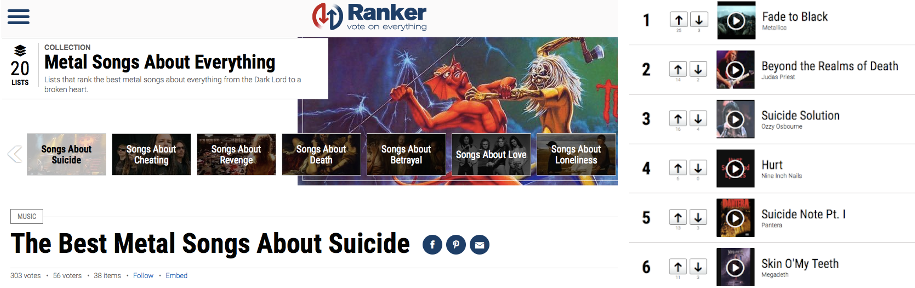

This genre category or song type is certainly recognized by the heavy metal audience. An example of this is the Ranker website listing the »20 Best Metal Songs« on »suicidal thoughts — not actions«, as voted for by the audience (see fig. 2).

Figure 2: Ranker’s 20 Best Metal Songs About Suicide. Ranker.

The top three suicide songs are »Fade to Black«, »Beyond the Realms of Death« and »Suicide Solution«.14 The more recent ones (»Hurt« by Nine Inch Nails and »Suicide Note Pt. 1« by Pantera) that have made the list demonstrate that the suicide ballad is a constant in heavy metal and its many sub-genre styles. However, identifying »Fade to Black« as a suicide song is important not only because it is cited in the US Senate hearing, but also because it is the first in a sequence of ballads offering a troubled »interior narrative« that is reflected elsewhere in thrash metal, with the likes of Megadeth and also the crossover hardcore/thrash band Suicidal Tendencies. In the latter instances, as will be illustrated, these songs are also identified with popular MTV videos.

Unearthing this evidence of the existence and circulation of suicide songs in this period is important in rebalancing the argument that »[t]he folk devil is more likely to be recruited from groups who cannot speak for themselves and have nobody to speak for them« (Critcher 2003, 145). While it remains the case that the popular genre of heavy metal and its fans were stigmatized and attacked by sections of the power elite in this period — and, in the case of the fans, lacked the means to contest their demonization — the existence of such songs and their popularity with heavy metal audiences suggests that a dialogic conversation or shared dialogue between metal musicians and metal fans was taking place, one concerned with addressing the experience of trying to »live through« this difficult economic and politically distorted period and, in the process, to cohere a shared sense of community, collective identity and empathy.

This leads to the argument that the thrash suicide ballad directly addresses the feelings of metal’s teen blue-collar fans in this period and offers a means of solace regarding the debilitating impact of neoliberal policies on their lives. It also suggests that the high youth suicide rate for blue-collar youth in this period was not a reflection of the popularity of metal but of the reality that there were no jobs for the former sons and daughters of skilled manual families — or just »dead-end« ones. Thinking about suicide is part and parcel of a sense that there is »no future« because the jobs that they normally would have done are just not there anymore. Alternatively, other songs released during this period, like Suicidal Tendencies’ »Institutionalized« or Metallica’s »Welcome Home (Sanitarium)«, address the development of local institutions such as the Back in Control Training Centre, that had a vested interest in labelling youth as depressed, unstable and in need of psychiatric assessment and 30-day detentions (Gaines 1998, 126; Males 1996, 219).

Exploring the Musical and Lyrical Features of the Suicide Ballad

The ways in which Metallica (and Megadeth) approach the ballad are quite distinctive and seem to be a deliberate musical strategy. How much of this was a conscious effort to distinguish their power-ballad style, or to what extent they looked to earlier hard rock and metal variants, is open to speculation. Although »Fade to Black«, for example, is based around conventional chords (Am, C, G, Em), it has an elaborate musical opening, combining electric and acoustic guitars, leading into the main picked arpeggio derived from a B minor power chord. This has a modal quality that works as a drone to allow a dark but virtuoso solo guitar embellishment, leading to the melodic hook of the song that combines both guitar tones. Hetfield’s voice is not clean but is subject to a phasing effect as it enters. The song is built around two sets of two melodic verses and an end verse, which are contrasting.15 Like most power ballads, the chorus enters after the second verse, employing power chords, but in the thrash style, these are heavily palm-muted and aggressively heavy. It is distinctive that there are no words in the repeated chorus. What is also distinctive is that the bridge leads to a different end section, which is introduced and performed in the thrash style, with descending chromatics and driving percussive guitars, leading to a »soaring, transcendent guitar solo« (Pillsbury 2006, 44), which »plays out« the piece.

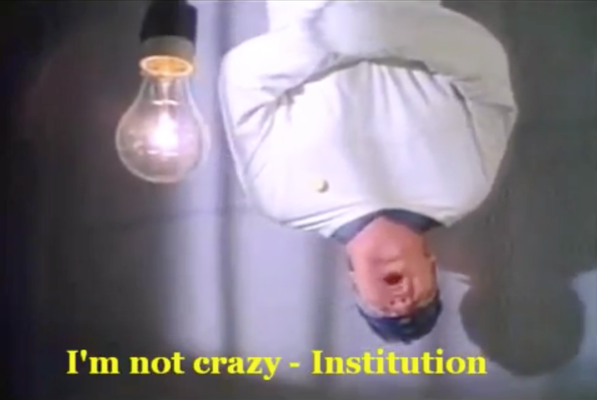

»Welcome Home (Sanitarium)« (from Master of Puppets, 1986), a song about a character who is falsely incarcerated in a mental institution, could be said to offer variations on this template. It opens in a similar way to »Fade to Black« with a picked arpeggio pattern, although the tone of the guitars is very dark, that again ends with a soaring melodic two-part guitar solo embellishment announcing the arrival of the first verse. The opening words of the song are very mournful: »Welcome to where time stands still / No one leaves and no one will«, indicating a profound sense of resignation that the inmates of the psychiatric ward »labelled mentally deranged« must learn to accept their fate. But the narrator of the song nevertheless dreams of a state of freedom, where there are »No locked doors, no windows barred / No things to make my brain seem scarred«. But it is nevertheless a »dream of reality«, from which the inmate awakes to the real: »They keep me locked up in this cage / Can’t they see it’s why my brain says rage«.16 Although James Hetfield has said the inspiration for the song was the book (1962) or film (1975), One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, it nevertheless seems to aptly describe the incarceration of troubled youth in this period. We also must wonder why Hetfield was drawn to this particular scenario, the suggestion being that there is more than a hint of insight and empathy to the choice. Unlike »Fade to Black«, the chorus enters after the third verse (the song is made up of two sets of three verses, two choruses and two end verses) employing even heavier power chords, palm muted in the thrash style. But the words, although they are sung in an aggressive full-throated manner by Hetfield, repeat the resignation of the intro: »Sanitarium, leave me be / Sanitarium, just leave me alone«. This is followed by a guitar embellishment in a similar manner to the opening refrain. The second chorus, ushered in by some words of resistance: »They think our heads are in their hands / But violent use brings violent plans«, leads into an extended bridge, with descending chromatics and driving percussive guitar riff interchanges, which eventually subdues to usher in the remaining two verses, leading to a soaring arpeggio-ornamented guitar solo from Kirk Hammett. »Welcome Home (Sanitarium)« is structured in a similar way to »Fade to Black«, but it differs in terms of its much more extended end section, which, while not resolving the problem of incarceration, does resist it both musically and lyrically via guitar and vocal aggression.

Suicide Song MTV Videos

Like Metallica, Megadeth have also released a series of songs about depression and suicide in the heyday of the thrash metal genre, such as »In My Darkest Hour« (1988), »Skin o’ My Teeth« (1992) and »A Tout Le Monde« (1994). But it is the latter song that is arguably the most poignant, announcing as it does the intention of the singer and composer of the band, Dave Mustaine, to commit suicide. It was also a very popular MTV-rotation video at the time, which dramatically illustrates the lyrics of the song.17 For example, at the beginning of the video, Mustaine’s name is being cut into a headstone, an image which is framed by the words: »These are the last words I’ll ever speak / They’ll set me free«. After this, we repeatedly see Megadeth fans, wearing the band T-shirt, jumping into an open grave, accompanied by the chorus refrain: »À tout le monde, à tous mes amis / Je vous aime, je dois partir« (»To all the world, to all my friends / I love you, I have to go«) (see fig. 3).

Figure 3: Megadeth: »A Tout Le Monde« (video). YouTube.

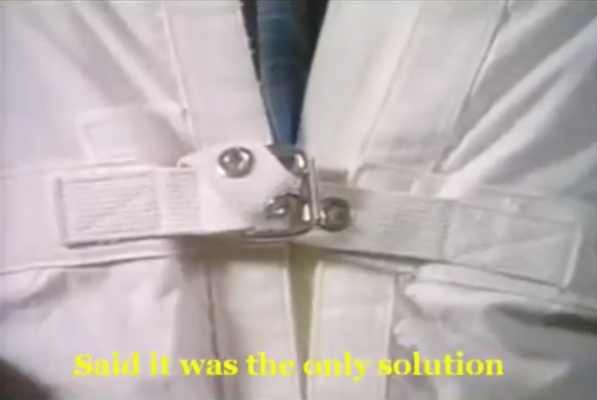

The aptly named crossover hardcore/thrash band Suicidal Tendencies (»Suicidal« to their fans) have lots of songs (although the majority are not ballads) about suicidal thoughts and troubled interior monologues. »Institutionalized« is one of their most poignant songs and MTV videos. It successfully satirizes the incarceration of youth, by their worried parents in the wake of the moral panic, in local psychiatric institutions. In the video, the parents do it themselves in their own home, first removing fan memorabilia so they can incarcerate their son in his bedroom cell. The first-person (son) narrator describes what follows: first they say he is on drugs, which accounts for his depression. Then they give him drugs to calm him down, so they can control him: »It’s too much work to help a crazy.« But his mates — the rest of the band — are on hand to liberate him from his bedroom imprisonment (see fig. 4).

Figure 4: Suicidal Tendencies: »Institutionalized« (video with lyrics). YouTube.

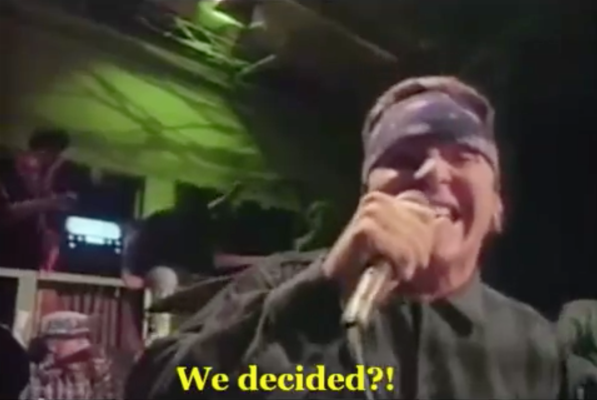

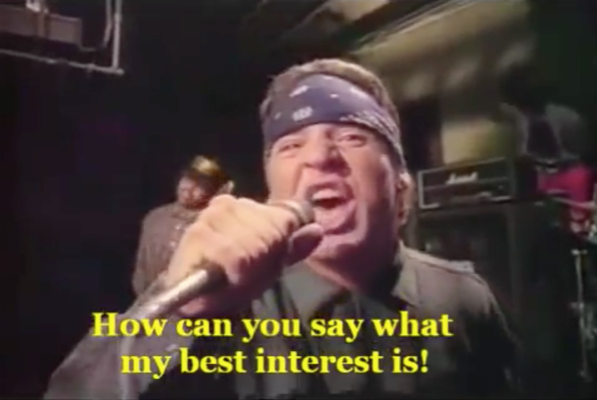

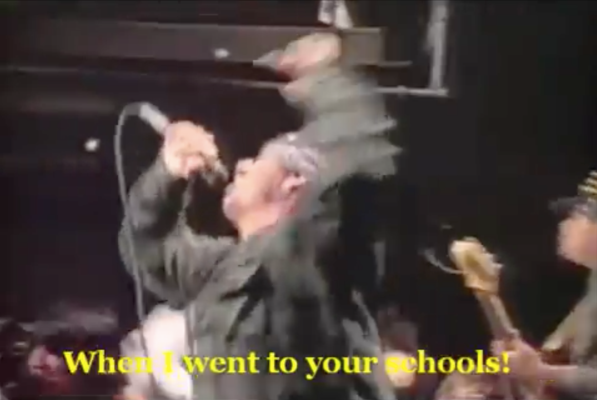

Once the rescue has been achieved, the video shifts to the band playing live in front of their hardcore/thrash fans, where a sense of community and protest is communicated by the band, and especially the rapper/lead singer Mike Muir, in a series of frames, reinforced by the concert footage of the fans moshing and stage diving, immersed in a collective cultural expression of resistance (see fig. 5).

Figure 5: Suicidal Tendencies: »Institutionalized« (video with lyrics). YouTube.

The line »We decided?!« announces a challenge to the definition of the elite claim’s makers: »My best interest?! […] How can you say what my best interest is?« The pivotal moment of expression is: »What are you trying to say? I’m crazy??? When I went to your schools, I went to your churches, I went to your institutional learning facilities« (cited in Gaines 1998, 126).18 Here, clearly Muir is speaking to »us« (the metal fans and community) about the situation they find themselves in and the controlling and dominating social structure that surrounds it — schools, religion, family, community and government (what structuralist philosopher Louis Althusser, following Antonio Gramsci, would define as the ISAs: Ideological State Apparatuses) — that are now stigmatising their sons and daughters as »folk devils«. Therefore, in this song/video, we have an example of folk devils fighting back, offering a critique of the powerful that argues that the depression, mental illness and madness suffered by metal fans defines — or indicts — the truth of their times.

Conclusion

This paper has offered a revision of previous research into moral panics about heavy metal and crossover-metal genres that were viewed as the cause of youth suicides in two different periods, 1984—1991 in the USA and 2008 in the UK. The key to the comparison was the issue of why the former was a successful moral panic and the latter a failed example. The evidence seemed to suggest that a failed moral panic was characterized above all by the would-be »folk devil« having both the (social media) means and the (articulate) ability to fight back, which the other lacked. However, a re-examination of the US Senate hearing (1985) on music and suicide songs revealed that the band Metallica and their song »Fade to Black« was also cited, which in turn pointed to a hitherto unexamined sub-genre song form: the thrash metal suicide ballad, which was prevalent at this time. Rather than confirming the claims of politicians and academic advocates of the negative impact of metal on youth, such songs offered a »dialogic« conversation between metal musicians and their fans that effectively addressed the experience of trying to »live through« this difficult economic and politically distorted period — and in the process, cohere a sense of community, collective identity and feelings of empathy, collective frustration and anger. All of this is captured in the songs and videos discussed, suggesting that there was an attempt to »fight back«, despite the overwhelming local and national state power and media rhetoric that sought to demonize both the bands and their fans.

Endnotes

-

It was assumed by media critics that The Black Parade was the place where youth went when they took their own lives. But, in fact, the concept album centres on »The Patient« dying from a terminal illness and joining with others in the bravery of collective resistance to their fate.↩︎

-

Andy R. Brown. 2017. »Songs in the Key of Depression, Suicide and Death: How Metal Musicians Sustained a Dialogue of Community with Their Fans in a Period of Moral Panic about Heavy Metal Music, 1984–1991«. Paper presented as part of the panel »Back to the Culture: 80s Heavy Metal as a Community of Creativity, Resistance and Difference« (Andy R. Brown [Chair], Kevin Ebert [Xavier University] and Ross Hagen [Utah Valley University]), at Boundaries and Ties: The Place of Metal Music in Communities, 3rd ISMMS Biennial International Conference, 9–11 June 2017, University of Victoria, Victoria, Canada.↩︎

-

Folk devils: »A concept widely used in the study of deviance, folk devils are social types that unite the negative qualities of which a society or group disapproves.« Oxford Reference. https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/oi/authority.20110803095826458. Accessed on 16 November 2023.↩︎

-

Of course, as Walser states, the origin of the phrase itself is the title of Ozzy Osbourne’s controversial song.↩︎

-

Zeppelin’s fourth album was untitled, except for four »runes« found on the inner gatefold sleeve, the first of which appears to spell out »ZoSo«.↩︎

-

1984 to 1991 was the most sustained period of popularity of heavy metal in the USA (Brown 2016, 61).↩︎

-

In the UK, a mid-market newspaper is one that combines entertainment with coverage of important news events. Notable titles are the Daily Mail and the Daily Express, identified by their »black« masthead in contrast to the »redtop« mastheads of the »down-market« tabloids, such as The Sun, Daily Mirror and Daily Star. The broadsheet press, originally a description of their size, are titles that are identified by their »serious« news coverage and in-depth analysis. Notable titles are The Guardian, The Times, The Telegraph and The Independent.↩︎

-

Parts of this subchapter are based on Brown 2018.↩︎

-

The list was aimed at promoting a rating system for the content of recorded music: X–Profane or sexually explicit; V–Violent; O–Occult; D/A–Drugs or Alcohol. Interestingly none of these categories refer to suicide, which only fully emerges in the US Senate hearing and the ensuing »suicide« indictment trials.↩︎

-

The »Warning: Explicit Content« label was adopted by the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) in 1987 and the British Phonographic Industry (BPI) in 2011.↩︎

-

Police found a cassette tape cover of the AC/DC album If You Want Blood You’ve Got It (1978) at the investigative scene (Gaines 1998, 25).↩︎

-

The phrase is taken from Gaines 1998, 155.↩︎

-

Yet clearly there are similarly dark and contemplative suicidal songs penned by other bands in this period (see below).↩︎

-

Since visiting the site in 2017, the list has changed its order of preference and added new entries, such as »Tourniquet« by Evanescence, although »Fade to Black« is still no. 1.↩︎

-

The full lyrics can be found at YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wpq7wn2YPYU. Accessed on 15 April 2024.↩︎

-

https://www.azlyrics.com/lyrics/suicidaltendencies/institutionalized.html. Accessed on 15 April 2024.↩︎

-

The video was (allegedly) banned by MTV because they thought it promoted suicide, but it was reinstated after changes were added to the end section which lists how many teenagers commit suicide every year and the message: »Suicide is not an answer. Get help.« See https://www.songfacts.com/facts/megadeth/a-tout-le-monde. Accessed 10 January 2023.↩︎

-

Gaines adds, »And whenever this song played at shows throughout the 1980s, kids would regularly bleat the lyrics out, line by line« (ibid.).↩︎

References

Bessman, Jim. 1990. »Judas Priest Defending Metal’s Faith: Offers a ›Painkiller‹ to Hardcore Fans«. Billboard, 3 November 1990: 46 and 52.

Boëthius, Ulf. 1995. »Youth, the Media and Moral Panics«. In Youth Culture in Late Modernity, ed. by Johan Fornas, and Goran Bolin, 39—57. London: Sage.

Brown, Andy R. 2011a. »No Method in the Madness? The Problem of the Cultural Reading in Robert Walser’s Running with the Devil: Power Madness and Gender in Heavy Metal Music and Recent Metal Studies«. In Can I Play With Madness? Metal, Dissonance, Madness and Alienation, ed. by Colin A. McKinnon, Niall Scott, and Kristen Sollee, 63—72. Oxford: Inter-Disciplinary Press.

Brown, Andy R. 2011b. »Suicide Solutions? Or, How the Emo Class of 2008 Were Able to Contest Their Media Demonization, Whereas the Headbangers, Burnouts or ›Children of Zoso‹ Generation Were Not«. Popular Music History 6, no. 1—2: 19—37.

Brown, Andy R. 2013. »Suicide Solutions? Or, How the Emo Class of 2008 Were Able to Contest Their Media Demonization, Whereas the Headbangers, Burnouts or ›Children of Zoso‹ Generation Were Not«. In Heavy Metal: Controversies and Countercultures, ed. by Titus Hjelm, Keith Kahn-Harris, and Mark LeVine, 17—35. London: Equinox Publishing.

Brown, Andy R. 2016. »The Ballad of Heavy Metal: Re-Thinking Artistic and Commercial Strategies in the Mainstreaming of Metal and Hard Rock«. In Heavy Metal Studies and Popular Culture, ed. by Brenda Gardenour Walter, Gabby Riches, Dave Snell, and Bryan Bardine, 61—81. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Brown, Andy R. 2018. »You’re All Partied Out, Dude! The Mainstreaming of Heavy Metal Subcultural Tropes, from Bill & Ted to Wayne’s World«. In Youth Subcultures in Fiction, Film and Other Media: Teenage Dreams (Palgrave Studies in the History of Subcultures and Popular Music), ed. by Nick Bentley, Beth Johnson, and Andrzej Zieleniec, 109—125. Cham: Palgrave Macmillian.

Brown, Andy R. 2025. »Thrash Metal«. In Bloomsbury Encyclopedia of Popular Music of the World XIII. New York: Bloomsbury Academic.

Brown, Jonathan. 2008. »EMO: Welcome to the Black Parade«. Independent, 23 May 2008. Accessed on 5 August 2024. https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/music/features/emo-welcome-to-the-black-parade-832854.html.

Chastagner, Claude. 1999. »The Parents’ Music Resource Centre: From Information to Censorship«. Popular Music 18, no. 2: 179—92.

Cohen, Stanley. (1972) 2002. Folk Devils and Moral Panics: The Creation of the Mods and Rockers. 3rd ed. London: Routledge.

Critcher, Chas. 2003. Moral Panics and the Media. Buckingham: Open University Press.

Frymer, Benjamin. 2006. »Sacred Profanities: Youth Alienation, Popular Culture, and Spirituality — An Interview with Donna Gaines«. InterActions: UCLA Journal of Education and Information Studies 2, no. 1. https://doi.org/10.5070/D421000566.

Gaines, Donna. (1990) 1998. Teenage Wasteland: Suburbia’s Dead End Kids. 2nd ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Lewis, Randy. 1986. »Handbook Weighs Heavy Metal for Parents«. Los Angeles Times, 22 August 1986. Accessed on 4 April 2024. https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1986-08-22-ca-17043-story.html.

Males, Mike A. 1996. The Scapegoat Generation: America’s War on Adolescents. Monroe, ME: Common Courage Press.

Martin, Linda, and Kerry Seagrave. 1993. Anti-Rock: The Opposition to Rock ’n’ Roll. New York: Da Capo Press.

McRobbie, Angela. 1994. Postmodernism and Popular Culture. London: Routledge.

McRobbie, Angela, and Sarah L. Thornton. 2000. »Re-thinking ›Moral Panic‹ for Multi-Mediated Social Worlds«. In Feminism and Youth Culture. 2nd ed., 180—97. London: Macmillan.

Moore, Ryan. 2010. Sells Like Teen Spirit: Music, Youth Culture, and Social Crisis. New York: New York University Press.

Pettinichio, Darlyne. 1986. The Back in Control Centre Presents the Punk Rock and Heavy Metal Handbook (pamphlet). Fullerton, CA: Back in Control.

Pillsbury, Glenn T. 2006. Damage Incorporated: Metallica and the Production of Musical Identity. New York: Routledge.

Raschke, Carl A. 1990. Painted Black: From Drug Killings to Heavy Metal — The Alarming True Story of How Satanism is Terrorizing Our Communities. New York: Harper Collins.

Richardson, James T. 1991. »Satanism in the Courts: From Murder to Heavy Metal«. In The Satanism Scare, ed. by James T. Richardson, Joel Best, and David G. Bromley, 205—17. New York: Aldine De Gruyter.

Rosenbaum, Jill Leslie, and Lorraine Prinsky. 1991. »The Presumption of Influence: Recent Responses to Popular Music Subcultures«. Crime and Delinquency 37, no. 4: 528—35.

Stack, Steven, Jim Gundlach, and Jimmie L. Reeves. 1994. »The Heavy Metal Subculture and Suicide«. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behaviour 24, no. 1: 15—23.

Ungar, Sheldon. 2001. »Moral Panic versus the Risk Society: The Implications of the Changing Sites of Social Anxiety«. British Journal of Sociology 52, no. 2: 272—91.

U.S. Congress. Senate. 1985. Record Labeling: Hearing Before the Committee on Commerce, Science and Transportation; United States Senate, Ninety-Ninth Congress, First Session on Contents of Music and the Lyrics of Records. September 19, 1985. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uc1.31210006120719.

Walser, Robert. (1993) 2014. Running with the Devil: Power, Gender, and Madness in Heavy Metal Music. Hanover, NH: Wesleyan University Press.

Weinstein, Deena. (1991) 2000. Heavy Metal: The Music and Its Culture. New York: Da Capo Press.

Young, Mary de. 1998. »Another Look at Moral Panics: The Case of Satanic Day Care Centers«. Deviant Behaviour: An Interdisciplinary Journal 19, no. 3: 257—78.

Figures

Figure 1: Photo: © Jenny Matthews/Alamy.

Figure 2: Ranker’s 20 Best Metal Songs About Suicide. Ranker. Accessed on 31 May 2017. https://www.ranker.com/list/metal-songs-about-suicide-self-harm/ranker-metal.

Figure 3: Megadeth: »A Tout Le Monde« (video). YouTube. Accessed on 15 April 2024. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aU-dKoFZT0A.

Figure 4: Suicidal Tendencies: »Institutionalized« (video with lyrics). YouTube. Accessed on 15 April 2024. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YvYMej1meZU.

Figure 5: Suicidal Tendencies, »Institutionalized« (video with lyrics). YouTube. Accessed on 15 April 2024. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YvYMej1meZU.