Adelaida Reyes, 1930–2021

A Pioneer in Ethnomusicological Minority Studies

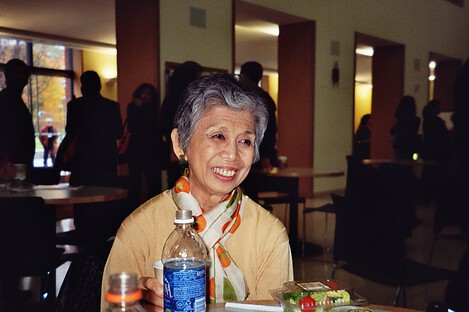

Adelaida Reyes © Ursula Hemetek

Adelaida Reyes © Ursula Hemetek

Adelaida Reyes passed away at her home after an extended illness in Fort Lee, NJ on August 24, 2021, at the age of 91. Throughout her career and as Professor Emerita at New Jersey City University, Professor Reyes led by example as an extraordinary scholar, humanitarian, and loving mentor to her students, peers, and family. Her generosity of spirit and intellect cannot be overstated.

Born in Manila, Philippines on April 25, 1930, Professor Reyes completed her undergraduate studies in music at St. Scholastica’s College, Manila, where she began work as a college lecturer immediately after graduation. During that period, she also worked as a music critic for the Philippine Evening News and The Manila Daily Bulletin, which earned her the attention of the Rockefeller Foundation. With the organization’s support, she was able to immigrate with her two young children to New York City, where she completed her M. Philosophy and Ph. D. at Columbia University while working multiple jobs to support her family. Her dissertation, “The Role of Music in the Interaction of Black Americans and Hispanos in New York City’s East Harlem,” was a ground-breaking work in urban ethnomusicology, nominated for the Bancroft Dissertation Prize in 1975. It marked the beginning of a career devoted to shifting the paradigms of her disciplines through rigorous fieldwork and incisive methodology. The importance of her contribution to discourses in international ethnomusicology is indisputable (see the detailed CV on MMRC’s website). In this obituary, I would like to address one specific aspect of her work: her contribution to minority studies in ethnomusicology. This account is very personal, because I had the privilege to cooperate closely with Adelaida Reyes over the last 20 years, and I will not only miss her invaluable scholarly advice but most of all the gentle, supportive, and wise woman so dear to me.

I remember very well when we first met: it was 2000 in Ljubljana at the first symposium of the ICTM Study Group on Music and Minorities in the Café at the Hotel Park, before the symposium started. I was immediately impressed by the scholar but at the same time by the gentleness of the person. Since then, we have experienced a lot together, and Adelaida’s support has been invaluable to me.

Adelaida was since then actively involved in the Study Group that I had the honour to chair from 1999–2017: as co-editor of the first publication in 2001 (Glasba in manjšine / Music and Minorities, edited by Svanibor Pettan, Adelaida Reyes, and Maša Komavec, Ljubljana: ZRC Publishing and Institute of Ethnomusicology SRC SASA), as Secretary (2005–2011), and as Vice-Chair (2011–2021). She attended all the Study Group symposia up to 2018 that took place regularly every two years. Her wise comments, especially concerning the ongoing discussions about defining the concept of minority have influenced and shaped the discourses within the Study Group.

When founding the MMRC in 2019, I asked her to join the Advisory Board, and readily she agreed. Her video message at MMRC’s kick-off event provides an impression – if only superficial – of her deep investment in the center’s aims. The discussion about the minority concept continued with her active participation, and the outcome is documented on this website. Adelaida always insisted on the fluidity of the concept as well as on its relational nature: “Minorities can only be defined in relation to a dominant group, since these two poles co-define each other in hegemonic discourse. This relation is a power relation, not a numerical one” (from MMRC’s definition of the minority concept).

In the introduction to the 1997 Charles Seeger Lecture, Kay Kaufman Shelemay points out how Adelaida’s own migratory experience influenced her work: “Her own life as an immigrant – a self-described ‘flying Dutchman’ – included heading the first Filipino family in Waldwick, NJ. These experiences, both good and bad, paved the way for her sensitivity to the complexity of the migration process and resonate in her later work among other refugees from Southeast Asia” (Shelemay, October 25, 1997). The list of her publications on the topic of music and minorities is not only impressive but has tangibly influenced the discipline. Shelemay highlights Adelaida’s doctoral dissertation “The Role of Music in the Interaction of Black Americans and Hispanos in New York City’s East Harlem” from 1975 as the beginning of urban ethnomusicology: “Here Adelaida Reyes Schramm took the lead in moving ethnomusicological scholarship into the domain of urban studies, providing at once a virtuoso case study of musical interaction in the complex Harlem environment and a detailed theoretical and methodological map for the practice of a new field called urban ethnomusicology” (Shelemay, October 25, 1997). Adelaida’s approach was also intrinsically interdisciplinary. The first of her articles I read was “Ethnic Music, the Urban Area, and Ethnomusicology,” published in 1979, not in an ethnomusicological forum, but the sociological journal Sociologus. Her way of dealing with ethnicity in this article as well as mapping the urban area as a field of research was tremendously influential for my further scholarly work. In writing such an article as early as 1979, she was far ahead of the mainstream discourses in ethnomusicology at that time. Likewise ground-breaking was her work on the music of refugees. She started to publish on this topic from the 1990s onward, see, for example, her guest-edited special issue on “Music and Forced Migration” of The World of Music (1990) or her book Songs of the Caged, Songs of the Free: Music and the Vietnamese Refugee Experience (1999). This work has influenced generations of researchers sharing Adelaida’s interest in the topic.

Many ethnomusicologists had the privilege of learning from Adelaida, either in direct personal contact or through her works. Her career was marked by her invaluable work as a teacher and mentor. In addition to teaching at New Jersey City University until her formal retirement in 1997, she served as a visiting professor and research fellow in universities across the United States, UK, and Europe, including Charles University (Prague), Columbia University (New York), the Juilliard School (New York), and the University of Oxford. My students love Adelaida’s texts, and I regularly find them quoted in seminar papers, bachelor or master’s theses, and doctoral dissertations. This latter way of transmitting her wisdom will continue. But for those of us who had the privilege to know her personally and to work with her, the loss is incredible.

In January 2021, Adelaida resigned as a member of MMRC’s Advisory Board due to health reasons. Both Board and MMRC’s team greatly deplored this decision. But to my great comfort, her support, expressed in wonderful, unique emails, that meant so much to me, was still there. On January 25, 2021, she wrote: “While I withdraw from active and official participation in the work of MMRC, my love for the MMRC and its goals, my faith in your leadership, in the dedication and superior qualifications of the Advisory Board members, and in the devotion of your ‘team’ remain. I await with joyful anticipation the recognition of MMRC's accomplishments in the world both of scholarship and of practice.” And on May 3, 2021, upon the publication of an article on a new research project, she wrote: “I guess I just can’t hold down my enthusiasm for the work MMRC has committed itself to. To quote Khalil Gibran: ‘May your tribe increase!’”

The MMRC will keep Adelaida’s memory alive. The inaugural issue of MMRC’s upcoming journal Music & Minorities (to be launched in 2021) will include an article on Adelaida’s contribution to ethnomusicological refugee studies. She actually planned to participate digitally in the launch event of the journal, as she wrote to me on August 16: “I am humbled and honored by the article you mention and would be happy to join you via Zoom on November 11 God willing. Your success with MMRC gives me great joy; I truly believe there is so much to know and understand about minorities in general and the contribution that the study of their musical life can make that remains untapped and that MMRC can bring to light.”

Adelaida’s visions will remain programmatic for the MMRC. I am personally grateful for having known and having learnt from such an outstanding, gentle, supportive, and wise woman.

Ursula Hemetek