© Fotostudio Balsereit

© Fotostudio Balsereit

Clemens Kreutzfeldt, M.A. M.Ed.

Clemens Kreutzfeldt joined the University of Music and Performing Arts Vienna as a research associate in 2019, where he is currently working on his dissertation “Music Trade in Antebellum Boston: Spaces of Transatlantic Exchange”. His topic emerged from the project “Musical Crossroads: Transatlantic Cultural Exchange 1800-1950”, led by Professor Melanie Unseld and funded by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF). Additionally, in 2022, he joined the FWF-project, “Musician Families: Constellations and Conceptions”, wherein he is currently developing ideas for a post-doctoral project. Prior to this, he was a research associate in the project “Musical Competitions: Framework and Database (1766-1870)” funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG) at the Institute of Musicology, University of Cologne, led by Professor Frank Hentschel (2016–2018).

In 2012, Clemens received his bachelor's degree in music, art and media from the University of Oldenburg. After studies at Kingston University, London, he continued his education in Oldenburg, receiving both a Master of Arts, with a focus on cultural history of music, and a Master of Education (music and art). He graduated in 2016 with a thesis on the British composer, pianist, and founding member of the Royal Philharmonic Society, Charles Neate (1784-1877).

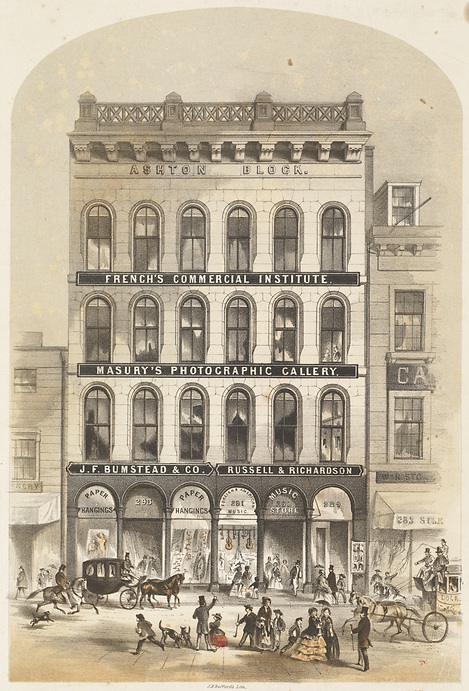

J. H. Bufford's Lith. "Russel & Richardson, Music Store, Foreign & American, 291 Washington Street, Boston." Print. 1856. Digital Commonwealth, https://ark.digitalcommonwealth.org/ark:/50959/8k71nw174 (accessed January 26, 2021))

J. H. Bufford's Lith. "Russel & Richardson, Music Store, Foreign & American, 291 Washington Street, Boston." Print. 1856. Digital Commonwealth, https://ark.digitalcommonwealth.org/ark:/50959/8k71nw174 (accessed January 26, 2021))

“Music Trade in Antebellum Boston: Spaces of Transatlantic Exchange”

My dissertation “Music Trade in Antebellum Boston: Spaces of Transatlantic Exchange” examines the Boston music trade between 1800 and 1860 as a space of transatlantic cultural transfer processes. The flourishing music market of that period reflects the musical and cultural life of the Atlantic metropolis and its transformations. It mirrors the economic, social and political developments, as well as the conditions of American musical culture. Significant influences on cultural life stemmed from the (crisis-related) migration from Europe as well as from an advancing industrial revolution, which increasingly eased mobility between the two continents.

The business model of Boston's music dealers of that time often included not only the mere buying, stocking, and selling of printed material, but also publishing activities, or the trade and production of instruments. In addition, their business premises functioned as social places where professional musicians and amateurs met and engaged in conversation. Information about upcoming concerts was distributed, concert tickets were sold and subscription lists were laid out. Furthermore, recommendations for suitable instrumental or singing teachers could be obtained. These multifaceted fields of activities were a requirement for a thriving business, and they made the music stores an elementary part of musical life. Thereby, music dealers were networkers par excellence and familiar with the European music culture and its actors. Many had practical experience and musical skills, acquired on both sides of the Atlantic, which had a crucial influence on their fields of activity in the music trade.

Their experiences resulted in the expansion of transatlantic trading spaces and the transfer of material goods such as printed music, instruments, or music-related literature, and they also shaped the social practices in their business premises. Boston music dealers were indispensable contacts for European musicians, who increasingly traveled to or immigrated to North America as it gained in economic attractiveness during this period. For these musicians, music dealers fulfilled important networking functions by having the necessary local connections to musicians, concert institutions or the music press. In fact, it was not uncommon for music dealers to act as managers for the concert activities of European musicians in the USA. Transatlantic transfer processes also found representations in their publishing activities. For example, music dealers followed the successes of traveling virtuosos in their publications; they advertised sheet music with information referring to European performance contexts, dedicatees or famous performers; last but not least, they considered the production of pirate copies as a possibility and necessity for their economic activities. The influence of music dealers on the repertoire of public concert life, as well as on the flourishing domestic music culture in North America, should not be underestimated. Their influence also raises questions regarding balancing processes between an awareness of a cultural mission and pure commerce.