History of the mdw

Lynne Heller, Severin Matiasovits and Erwin Strouhal (as of Dec. 2020).

Early History

It was at the beginning of the 19th century that the first public calls arose to open a conservatory of music in Vienna.

An “Outline for an Institution of Music Education for the Capital City and Imperial Residence of the Austrian Imperial State”, published in 1811, urged the creation of a “public institution, to be formally established and managed by the state.”

Just one year later, these considerations led to the formation of the “Society of the Friends of Music of the Austrian Imperial State” (Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde des österreichischen Kaiserstaates, now known simply as the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde), which was to play a key role in the formalisation of music education in Vienna.

From its Founding to the Revolution (1817 – 1848)

The Society’s initial plans were ambitious and oriented towards the Paris Conservatoire, which had been founded in 1795 as Europe’s first state institution of music education.

The Society’s initial plans were ambitious and oriented towards the Paris Conservatoire, which had been founded in 1795 as Europe’s first state institution of music education.

In Vienna, however, what was eventually established in 1817 was at first just a four-year singing school led by Antonio Salieri in which two teachers taught 12 students each in a building on Singerstraße that was known as Zum Roten Apfel. This marked the birth of the Conservatory, later to become the mdw – University of Music and Performing Arts Vienna.

The school was approved subject to the stipulation that particular attention be paid to church music and that pre-service public school teachers be permitted to participate in the singing classes.

The school was approved subject to the stipulation that particular attention be paid to church music and that pre-service public school teachers be permitted to participate in the singing classes.

At that time, Austria’s education authority—and hence the state—was placing increased emphasis on good musical training, since the schools and churches played a central role in upholding musical life particularly in villages and small towns.

The first instrumental lessons (on the violin) began in 1819, and by 1827 the Conservatory was offering instruction in most orchestral instruments. Piano instruction was added in 1833, but only as a minor subject.

In 1820, a necessary move brought the Society to the Gundelhof (Brandstätte 5 / Bauernmarkt 4), from which it moved two years later to occupy the Haus zum roten Igel (Tuchlauben 12), a building that it then purchased in 1829 and proceeded to extensively remodel. Soon, however, the available space there proved insufficient, for which reason calls arose for a new Society building.

In 1820, a necessary move brought the Society to the Gundelhof (Brandstätte 5 / Bauernmarkt 4), from which it moved two years later to occupy the Haus zum roten Igel (Tuchlauben 12), a building that it then purchased in 1829 and proceeded to extensively remodel. Soon, however, the available space there proved insufficient, for which reason calls arose for a new Society building.

For the initial decades of the Conservatory’s existence, enrolment data is spotty: the extant records show nearly 300 (18% female / 82% male) students in 1830, with around 200 (25% female / 75% male) in 1840. By 1840, the number of teachers had risen to 18.

The Conservatory’s financial situation had been difficult from the very beginning. Even the introduction of tuition in 1829 did little to improve its shaky finances, and by 1837 the institution was practically bankrupt.

Two requests for a takeover by the state or the territorial estates were rejected, but the Conservatory did begin receiving state subsidies in 1843 as well as support from the City of Vienna beginning in 1851—marking the advent of political influence over the institution. In the wake of 1848’s revolutionary unrest, the Conservatory was forced to close. However, efforts were made to keep the institution alive or found it anew. Thanks to teachers willing to work for free as well as support from the Ministry of Education, it proved possible to continue training students for a short period of time during which the school was known as the “Vienna Conservatory of Music” (Wiener Conservatorium der Musik); instruction was provided at Ballplatz 22, which is today’s Ballhausplatz 5.

Two requests for a takeover by the state or the territorial estates were rejected, but the Conservatory did begin receiving state subsidies in 1843 as well as support from the City of Vienna beginning in 1851—marking the advent of political influence over the institution. In the wake of 1848’s revolutionary unrest, the Conservatory was forced to close. However, efforts were made to keep the institution alive or found it anew. Thanks to teachers willing to work for free as well as support from the Ministry of Education, it proved possible to continue training students for a short period of time during which the school was known as the “Vienna Conservatory of Music” (Wiener Conservatorium der Musik); instruction was provided at Ballplatz 22, which is today’s Ballhausplatz 5.

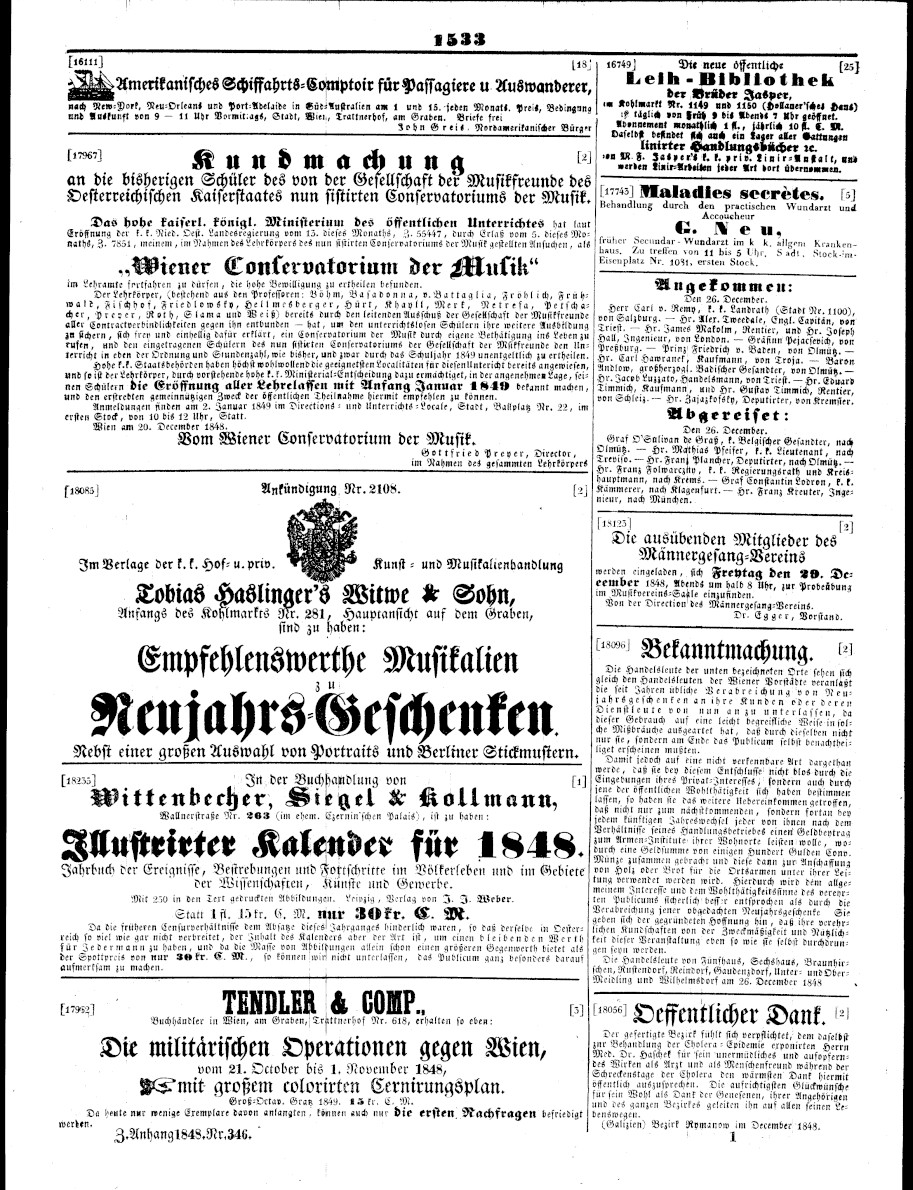

Pictures

Antonio Salieri, © mdw-Archive

Anna Fröhlich, the first woman to teach at the Vienna Conservatory, taught voice from 1819 to 1854. © mdw-Archive

Haus zum roten Igel on Tuchlauben in Vienna, 1830. © ÖNB/Wien FKB-Vues Österreich-Ungarn, Wien IV, Innere Stadt, b) Plätze 1

Announcement of the “Vienna Conservatory of Music”, 1848. © Wiener Zeitung, 29.12.1848, S. 1533; ANNO/ÖNB

From Reopening to Nationalisation (1851 – 1909)

In 1851, with the Revolution of 1848 having run its course, the Conservatory resumed operations. And thanks to financial support from the Austrian state and the city, conditions at the Conservatory soon improved. However, a dispute arose within the Society as to the Conservatory’s true purpose: one side favoured basic instruction on a broad scale, while the other side favoured devoting the institution’s limited resources to a smaller number of more advanced students. Initial calls to establish a tertiary-level institution (a Hochschule) likewise emerged.

1852 saw declamation introduced as a teaching subject, which was followed by the creation of a class for opera in 1853—laying the cornerstone for the Opera Department (formally established in 1870) and the Department of Acting (1874).

Over the second half of the nineteenth century, enrolment continually increased: in 1855 there were 195 students, with 444 in 1865, nearly 650 in 1875, and close to a thousand—965, to be exact—by 1890. While the share of female students had been just under 28% in 1855, it reached the 50% mark in 1865 and continued to grow thereafter. With few exceptions, the number of female students was to remain far in excess of 50%—frequently even exceeding 60%—into the twentieth century.

Following the institution’s reopening in 1851, it employed 16 teachers; by 1909, that figure had risen to 69. The share of women was extremely low: a grand total of 19 women taught at the Conservatory between 1817 and 1909, of whom only three are known to have taught outside of the Voice Department.

As an institution oriented toward training students from the lands of the Habsburg Monarchy, the Conservatory appears to have opened itself up to foreign students in a broad-based way only beginning in the late 1870s.

The Conservatory initially admitted children between eight and twelve years of age, but the mid-nineteenth century saw the minimum age raised somewhat—with a higher age necessary to begin studying certain subjects such as wind instruments or voice. Admission to the Conservatory was granted following an entrance examination, but there were at first no clear standards in terms of necessary prior knowledge or artistic skills. Beginning in the 1870s, the Conservatory began offering a one-year preparatory course covering fundamental knowledge and skills that would be expected in the entrance examination.

The Conservatory initially admitted children between eight and twelve years of age, but the mid-nineteenth century saw the minimum age raised somewhat—with a higher age necessary to begin studying certain subjects such as wind instruments or voice. Admission to the Conservatory was granted following an entrance examination, but there were at first no clear standards in terms of necessary prior knowledge or artistic skills. Beginning in the 1870s, the Conservatory began offering a one-year preparatory course covering fundamental knowledge and skills that would be expected in the entrance examination.

1869 bezog die Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde das neu errichtete Musikvereinsgebäude am Wiener Karlsplatz, wo auch der Unterricht des Konservatoriums stattfand.

1896, a pivotal year in the history of Austrian music education, saw teacher training courses formally introduced at the Conservatory. All the way back in 1863, a state board of examiners had been established that was authorised to issue state certificates licensing the establishment of private music schools as well as licensing music teachers to teach in public schools. The diplomas earned by completing this new teacher training programme were made equivalent to those that could be earned in the existing state examinations in music.

Although subsidies provided by the state were being constantly increased, it was clear that the privately run Society would soon lack the resources to bear its share of the steadily increasing costs. What’s more, pressure on the state to take responsibility for the training being offered was growing apace—especially in view of the teacher training courses’ introduction in 1896. Moreover, the state subsidies had become so great at this point that there was no longer any correlation between the state authorities’ mere monitoring function and their financial contribution.

It was thus that on 1 January 1909, the Conservatory was nationalised by imperial resolution.

Picture

Vienna’s Musikverein Building on Karlsplatz, ca. 1870. © mdw-Archive

From Imperial-Royal Academy to the Anschluss (1909 – 1938)

With nationalisation, the state assumed fiscal responsibility for the country’s foremost music school. The administrative structure of the Imperial-Royal Academy of Music and Performing Arts, as the former Conservatory became known when it was nationalised, was headed by a civil servant appointed by the Ministry as its president. This civil servant, Karl (Ritter von) Wiener, was assisted by a board of trustees and an artistic director, the first of whom was Wilhelm Bopp. Wiener, for his part, also held several other music-relevant leadership positions and thus played a key role in Austria’s cultural landscape at large. Simultaneously with nationalisation, the last remaining cases in which women were excluded from individual programmes of study were eliminated—but the share of female teachers was still only around 10%, while nearly 56.5% of the nearly 900 students were female.

With nationalisation, the state assumed fiscal responsibility for the country’s foremost music school. The administrative structure of the Imperial-Royal Academy of Music and Performing Arts, as the former Conservatory became known when it was nationalised, was headed by a civil servant appointed by the Ministry as its president. This civil servant, Karl (Ritter von) Wiener, was assisted by a board of trustees and an artistic director, the first of whom was Wilhelm Bopp. Wiener, for his part, also held several other music-relevant leadership positions and thus played a key role in Austria’s cultural landscape at large. Simultaneously with nationalisation, the last remaining cases in which women were excluded from individual programmes of study were eliminated—but the share of female teachers was still only around 10%, while nearly 56.5% of the nearly 900 students were female.

The available areas of study were expanded with the establishment of the Kapellmeister School (1909) and the Department of Church Music (1910), the addition of new minor subjects, and an increase in the number of theoretical and scholarly lectures. The duration of study was increased in individual programmes, and instruction was generally intensified thanks to increases in the length of weekly lessons.

In 1913, the Academy (up to then still located at the Musikverein) was able to move to the building on Lothringerstraße that had been planned by architects Ferdinand Fellner, Hermann Helmer, and Ludwig Baumann. This location, however, soon proved too small.

In 1913, the Academy (up to then still located at the Musikverein) was able to move to the building on Lothringerstraße that had been planned by architects Ferdinand Fellner, Hermann Helmer, and Ludwig Baumann. This location, however, soon proved too small.

In the wake of World War I’s conclusion and the monarchy’s simultaneous collapse, the Academy was reorganised once yet again—this time with an eye to democratisation: the rights to codetermination in artistic and educational matters demanded by its teachers were granted. The teachers thereupon elected the conductor Ferdinand Löwe as their new director. He was assisted by four division heads, and specific responsibilities were given to committees from the individual divisions as well as to an academic senate.

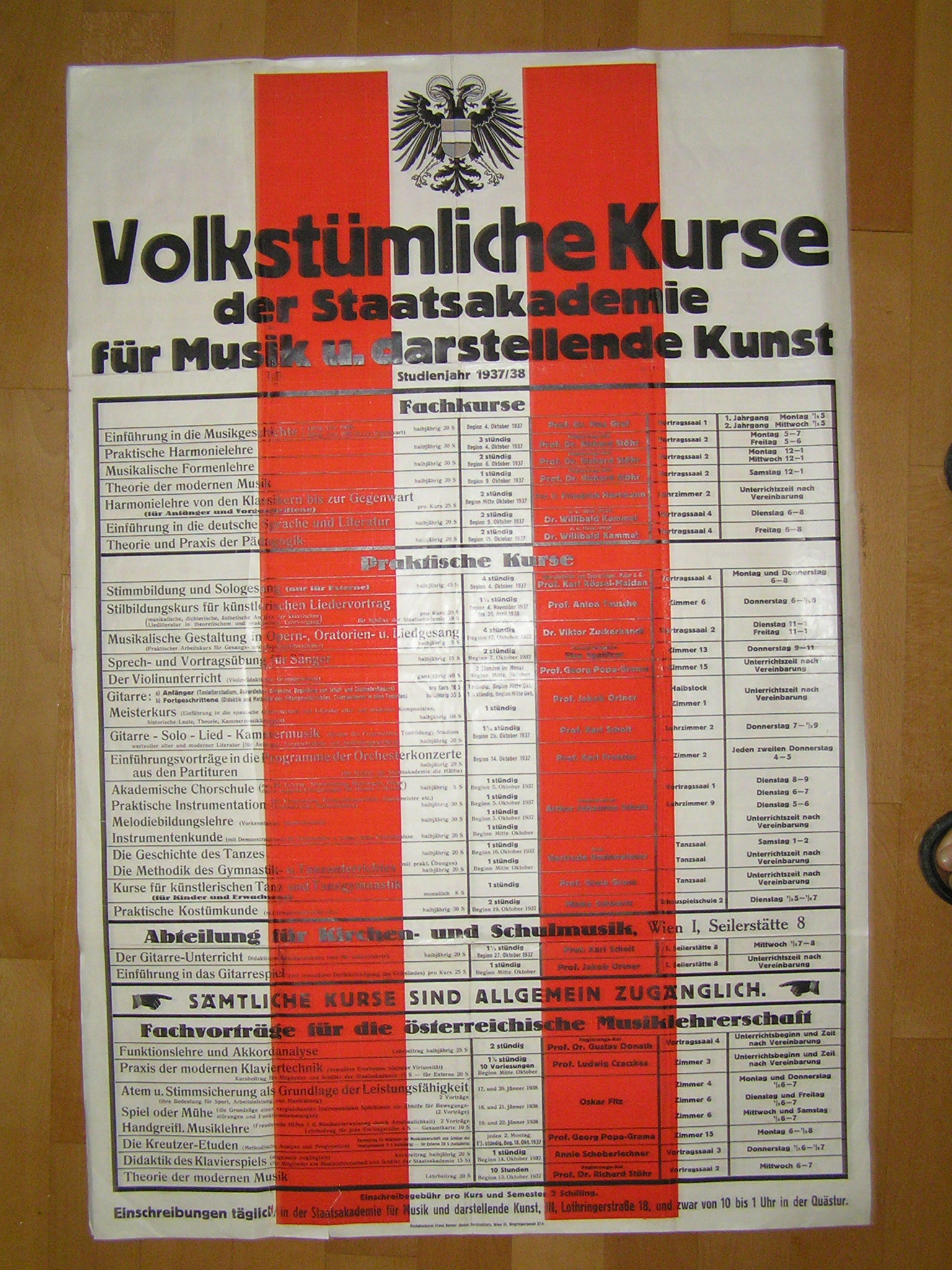

One of the reforms that they implemented entailed the establishment of so-called “Popular Courses” (Volkstümliche Kurse), continuing and adult education courses open to both Academy students and non-students that were intended to enhance the musical education of a broader swath of the Viennese public.

One of the reforms that they implemented entailed the establishment of so-called “Popular Courses” (Volkstümliche Kurse), continuing and adult education courses open to both Academy students and non-students that were intended to enhance the musical education of a broader swath of the Viennese public.

The interwar period witnessed significant expansion of course and programme offerings, partly in combination with more major organisational changes: an Artistic Dance course was offered in 1920, after which the subject was established as a major under the aegis of Gertrude Bodenwieser.

In 1928, a Radio Speaking and Radio Directing course became available in response to the advent of radio, which had arrived in Austria four years before. Another reaction to the changes occurring in society was the expansion of instructional offerings by saxophone and jazz trombone. 1928/29 saw the training of educators reorganised from the ground up with the creation of a “Music Education Seminar” (Musikpädagogisches Seminar), which became part of the newly formed Department of Church and School Music in 1933. Plans to set up a film studio, however, fell apart in 1936 and were postponed indefinitely.

A severe break in the institution’s history was its 1924 division into an Academy and a (more explicitly tertiary-level) Fachhochschule for Music and Performing Arts. Initial efforts to attain tertiary-level status for the Academy had arisen shortly following the end of the Monarchy. These efforts were aimed at demonstrating the unbroken significance of the Austrian rump state in cultural politics with an eye to not falling behind the various foreign academies of music in terms of status. The separation into an Academy and a Fachhochschule entailed a higher share of theoretical subjects at the latter, underscoring the equality of artistic training and academic study.

These two institutions’ entanglement both organisationally and in terms of personnel, coupled with the increasing severity of the political interference to which they were subject, led to ongoing conflicts and deep division among faculty members. For these reasons, 1931 saw the Fachhochschule abolished—with the programmes of study that had been offered there being reintegrated into the Academy. The Fachhochschule’s Acting and Directing Seminar, founded under the aegis of Max Reinhardt in 1928/29, continued its operations on an independent basis over the years that followed—with the Ministry of Education providing only the teaching and rehearsal spaces at the Schlosstheater as an in-kind subsidy.

These two institutions’ entanglement both organisationally and in terms of personnel, coupled with the increasing severity of the political interference to which they were subject, led to ongoing conflicts and deep division among faculty members. For these reasons, 1931 saw the Fachhochschule abolished—with the programmes of study that had been offered there being reintegrated into the Academy. The Fachhochschule’s Acting and Directing Seminar, founded under the aegis of Max Reinhardt in 1928/29, continued its operations on an independent basis over the years that followed—with the Ministry of Education providing only the teaching and rehearsal spaces at the Schlosstheater as an in-kind subsidy.

At the time at which the Fachhochschule was established, the two institutions were attended by 1,530 students altogether (52.2% female /47.8% male), with the share of tertiary-level (Fachhochschule) students at just under 10% (140 individuals; 49 female / 91 male). In the Fachhochschule’s final year of its existence, it was attended by 18% (220 individuals; 122 female / 98 male) of altogether 1,243 students (51.6% female / 48.4% male).

With the Fachhochschule eliminated, artistic, financial, and administrative leadership of the recombined State Academy was entrusted to the Academy’s former president Karl Wiener, who was brought back from retirement to assume the post. The institution’s extensive autonomy thus ceased to exist, with all of the bodies that had been involved in academic co-determination being dissolved. Wiener pushed for the institution’s reorientation, introducing master classes and aiming to reduce the number of students: admission criteria were made more strict, the duration of study was reduced, and theoretical/academic subjects were downgraded in their importance. In order to free up financial resources for the appointment of renowned artists, he let some faculty members go—with the remaining faculty receiving only one-year contracts and lower pay.

November 1932 saw the ministerial official Karl Kobald assume leadership of the Academy. Kobald worked to increase the institution’s public renown and initiated the organisation and conduct of international competitions.

His term of office was also, however, marked by the increasing ideological and political permeation of Austrian educational institutions by the Austrofascist system of rule. This was reflected in the Academy’s statutes of 1933 and entailed the severe disadvantaging of faculty.

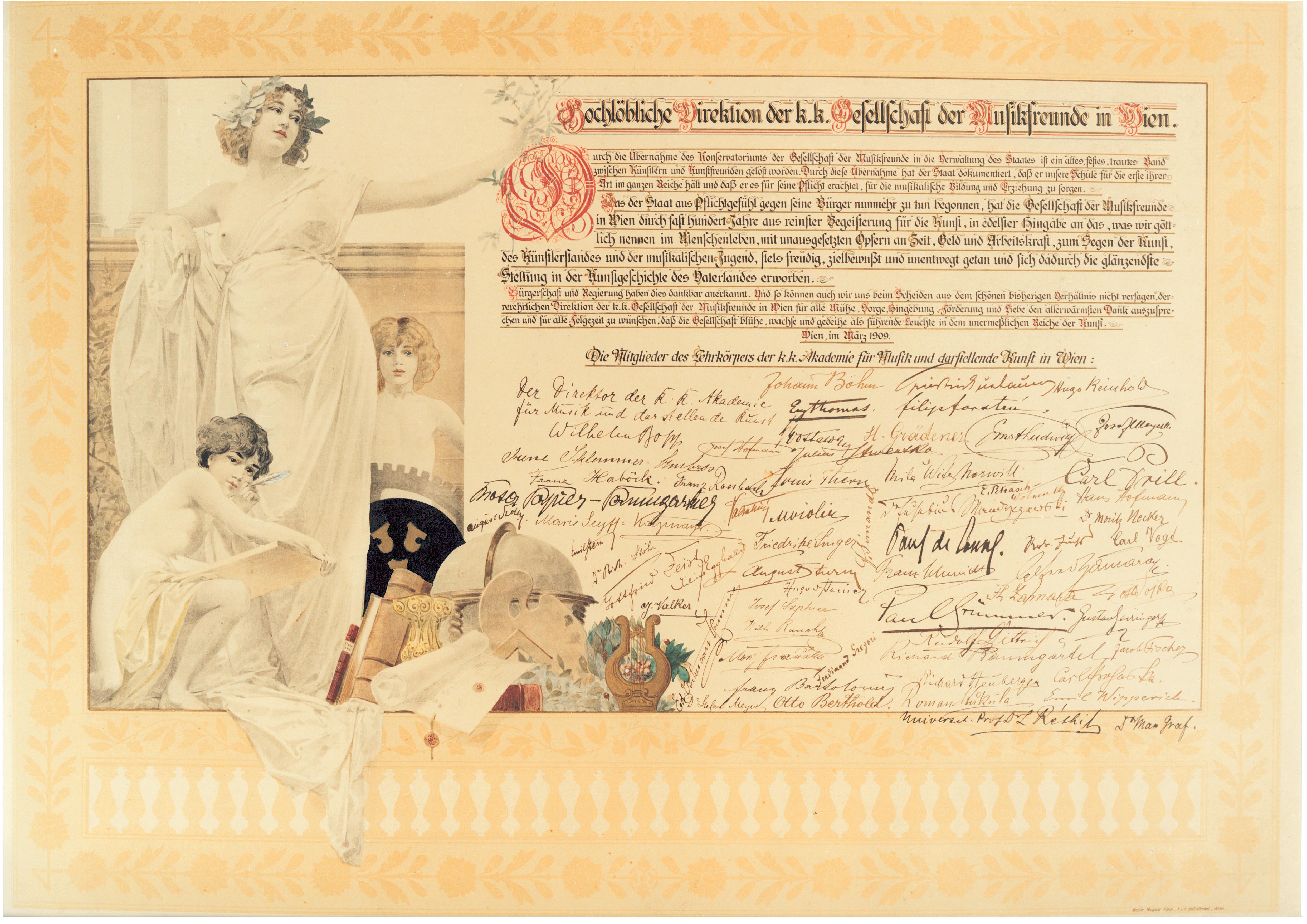

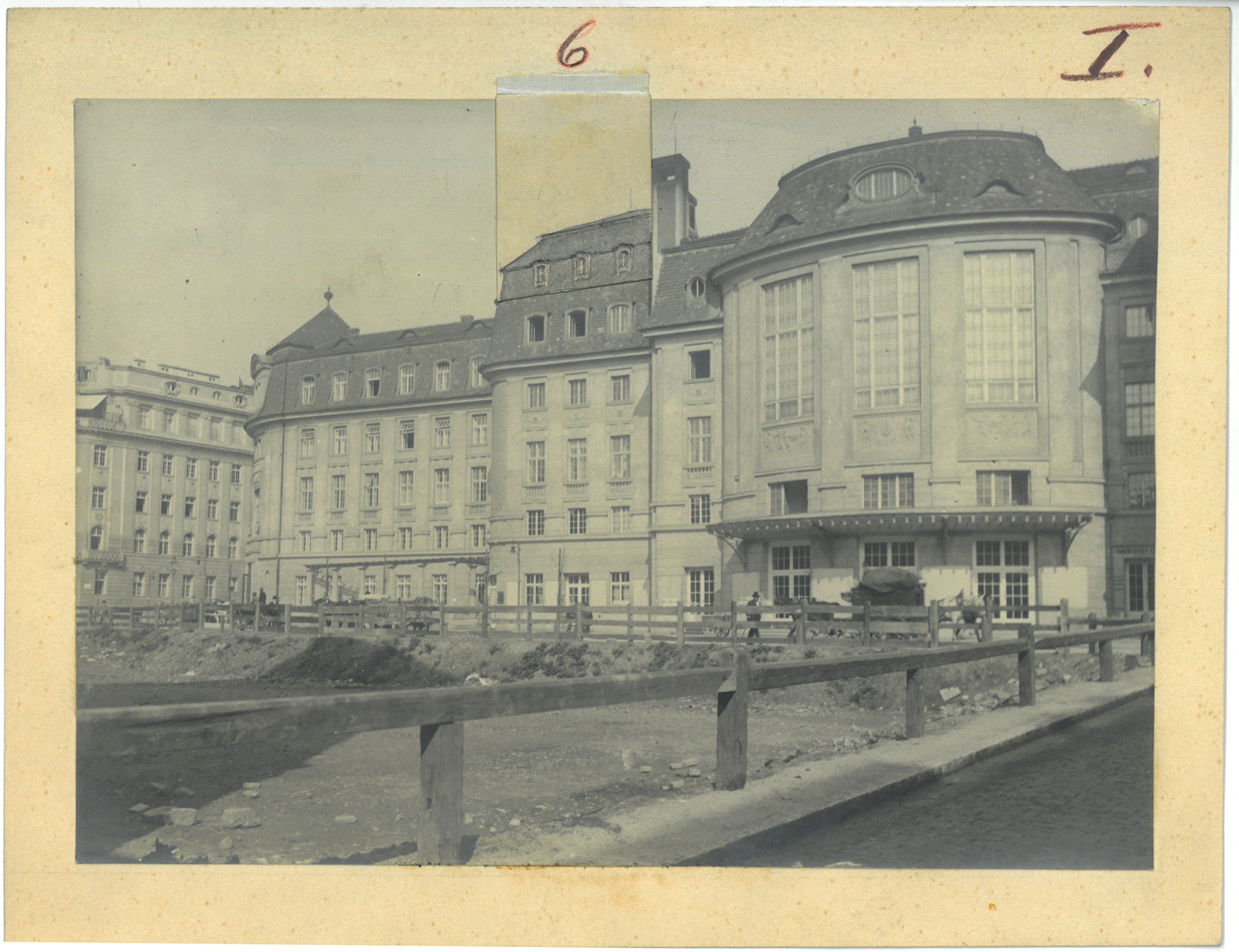

Pictures

Certificate of gratitude presented by the Conservatory faculty to the Society of Friends of Music on the occasion of the Conservatory’s nationalisation in 1909. © Archive of the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde

The newly constructed academy building in Lothringerstraße, 1914. © mdw-Archive, 343/Pr/1914

Poster for the “Popular Courses”, 1937/38. © mdw-Archive

Max Reinhardt with his students, 1920s. © mdw-Archive (Anton Schwandner)

The Academy under Nazi Rule (1938 – 1945)

On 13 March 1938, an SS Signal Corps unit moved into the main building of the Academy on Lothringerstraße—and on 15 March, Kobald was removed from his post and replaced by Alfred Orel as provisional head. That same day, Orel fired those faculty members who were no longer to be tolerated at the institution on account of their Jewish descent. In sum, the firings ordered on “racial”, political, and probably also personal grounds by the National Socialist administration following their takeover amounted to nearly 50% of faculty. Around 100 students (ca. 10%) were likewise forced to leave the Academy on “racial” grounds.

On 13 March 1938, an SS Signal Corps unit moved into the main building of the Academy on Lothringerstraße—and on 15 March, Kobald was removed from his post and replaced by Alfred Orel as provisional head. That same day, Orel fired those faculty members who were no longer to be tolerated at the institution on account of their Jewish descent. In sum, the firings ordered on “racial”, political, and probably also personal grounds by the National Socialist administration following their takeover amounted to nearly 50% of faculty. Around 100 students (ca. 10%) were likewise forced to leave the Academy on “racial” grounds.

After just a few months, Orel was removed from office and replaced by Franz Schütz, who was to head the Academy until 1945.

After just a few months, Orel was removed from office and replaced by Franz Schütz, who was to head the Academy until 1945.

Since the demise of the Hochschule in 1931, the number of students had held steady at around 1,000—but over the course of the war years, their number would dwindle to less than 500.

Schütz aimed to develop an institution oriented towards virtuosity and limited to “true” talents—standards that he applied in equal measure to both students and faculty—and he sought to run the institution free from political interference.

The Nazification process at the Academy brought with it the immediate suspension of the Popular Courses, while the Max Reinhardt Seminar—which Reinhardt had overseen privately up to that point—saw twelve of its teachers dismissed. It was nationalised and became the Schönbrunn Acting and Directing Seminar (Schauspiel- und Regieseminar Schönbrunn). In May 1940, the school was moved to Palais Cumberland in Penzing, while Schlosstheater Schönbrunn continued to be used as a venue.

Church music< was separated from school music, and training for music educators (including school music teachers) was transferred to the newly founded Music School of the City of Vienna.

1939 saw the Academy designated a Hochschule 1939, and it was upgraded to Reichshochschule-status in 1941. At that point, music education was reintegrated in order to ensure a level equal to that of the German Reich’s other such institutions. A mandatory second (academic) teaching subject for future teachers was introduced, and this requirement remained in place after the war.

In the autumn of 1944, all arts academies were ordered closed, but this directive was implemented only in part. Those who were permitted to continue their studies were mainly education students. The last artistic teaching diploma examinations prior to the war’s conclusion were held in March 1945.

Pictures

The Academy building in Lothringerstraße, May 1938. © Austrian National library, Vienna S 208/16

Franz Schütz, ca. 1940. © Die Pause 5, 6 ([1940]), 18

Liberation and Post-War Developments (1945 – 1970)

After the war, the Reichshochschule reverted to its former status of (state) academy. The denazification process that ensued saw numerous faculty members dismissed, although several of them were reappointed later on. The Arts Academies Act (Kunstakademiegesetz) took effect in 1948, followed by new organisational statutes in 1949, under which the institution was divided into nine (and later ten) departments. As a member of the newly created institutional category of “arts academy”, the Academy was headed by its own president. Furthermore, a distinction had been drawn between “students” and “university students” of art. And as an institution providing education up to the highest level, the Academy was now considered equal to other Austrian tertiary-level academic institutions in some respects. Its president, Hans Sittner, was advised by a general assembly of faculty members as well as by a council made up of the institution’s annually elected department chairs.

After the war, the Reichshochschule reverted to its former status of (state) academy. The denazification process that ensued saw numerous faculty members dismissed, although several of them were reappointed later on. The Arts Academies Act (Kunstakademiegesetz) took effect in 1948, followed by new organisational statutes in 1949, under which the institution was divided into nine (and later ten) departments. As a member of the newly created institutional category of “arts academy”, the Academy was headed by its own president. Furthermore, a distinction had been drawn between “students” and “university students” of art. And as an institution providing education up to the highest level, the Academy was now considered equal to other Austrian tertiary-level academic institutions in some respects. Its president, Hans Sittner, was advised by a general assembly of faculty members as well as by a council made up of the institution’s annually elected department chairs.

The era of post-war reconstruction witnessed the establishment of numerous specialised artistic and academic programmes of study and departments as well as the encouragement of research and academic publishing from the 1950s onward. The Film Academy as well as the Department of Music Sociology and the Department of Folk Music Research and Ethnomusicology, among other features of the present-day University, date back to this period.

The era of post-war reconstruction witnessed the establishment of numerous specialised artistic and academic programmes of study and departments as well as the encouragement of research and academic publishing from the 1950s onward. The Film Academy as well as the Department of Music Sociology and the Department of Folk Music Research and Ethnomusicology, among other features of the present-day University, date back to this period.

A major encumbrance was the urgent need for space: during this period, the Academy had hardly any instructional rooms that could hold more than 30 people; what’s more, the Akademietheater—which had been the Academy’s largest performing space—was lost to the Burgtheater. Numerous projects aimed at finding a long-term solution to these problems failed, and it was only in 1968 that the opportunity to use the former Ursuline abbey on Johannesgasse provided palpable relief. In 1970, the mdw acquired Palais Festetics on Metternichgasse (Department of Film and Television), but the increasing need for space was eventually to necessitate a total of 26 acquisitions and lease arrangements before the end of the 20th century.

During the initial post-war years, the number of students at first rose slowly but steadily, followed by a marked increase beginning in 1955. While just over 1,000 students (48.7% female / 51.3% male) attended the institution in 1950, enrolment rose to approximately 1,300 (48% female / 52% male) in 1955; 10 years later, over 1,700 students (46.3% female / 53.7% male) were enrolled at the mdw. The space-related difficulties were exacerbated by more than just the rising numbers of students, for a continual increase in the need for space was also entailed by the constant expansion of course offerings.

Pictures

Hans Sittner (1903–1990) was President of the Academy from 1946 to 1971. © mdw-Archive

The Academy’s general assembly of faculty, 1967. © mdw-Archive

From Academy to University (1970 – 1999)

The Universities of the Arts Organisation Act (Kunsthochschul-Organisationsgesetz [KHOG]) of 1970 effected the conversion of Austria’s Akademien [academies] of the arts to Hochschulen [alternately rendered as “academies”, “colleges”, or “universities” in English) under the statutory administration of a rector, and a close election produced Georg Pirckmayer as the first rector of the newly minted Hochschule.

The Universities of the Arts Organisation Act (Kunsthochschul-Organisationsgesetz [KHOG]) of 1970 effected the conversion of Austria’s Akademien [academies] of the arts to Hochschulen [alternately rendered as “academies”, “colleges”, or “universities” in English) under the statutory administration of a rector, and a close election produced Georg Pirckmayer as the first rector of the newly minted Hochschule.

The Universities of the Arts Study Act (Kunsthochschul-Studiengesetz [KHStG]) of 1983 regulated all of the major degree and non-degree programmes at Austria’s six university-level institutions of artistic training, granting them the right to award the title of Magistra artium / Magister artium to graduates of their degree programmes. The teacher training programmes had already been awarding this title since 1971 on the basis of their being coupled with qualifications in a second teaching subject earned at a standard academic university. Thanks to the KHStG, school music teachers now had the additional option of pursuing a doctorate at the mdw.

1991, with Rector Helmut Schwarz at the helm, witnessed the launch of the International Summer Academy Prague Vienna Budapest. Now known as isa – International Summer Academy, it has taken place on an annual basis ever since (in combination with isaScience since 2013) and is now the mdw’s largest ongoing project.

1991, with Rector Helmut Schwarz at the helm, witnessed the launch of the International Summer Academy Prague Vienna Budapest. Now known as isa – International Summer Academy, it has taken place on an annual basis ever since (in combination with isaScience since 2013) and is now the mdw’s largest ongoing project.

In 1988, more space became available for the mdw’s music education programmes thanks to the acquisition of part of the Salesian convent, and the mdw’s 1996 takeover of the former facilities of the University of Veterinary Medicine laid the cornerstone for its present-day main campus.

With the passage of the Universities of the Arts Organisation Act (Bundesgesetz über die Organisation der Universitäten der Künste – KUOG) of 1998, existing Hochschulen were converted into Universitäten [universities] of the arts.

Back when the Academy became a Hochschule, around 2,000 students (47.5% female / 52.5% male) had been enrolled. But from that point onward, enrolment rose sharply to total over 3,000 (52.5% female / 47.5% male) by the beginning of the 1990s.

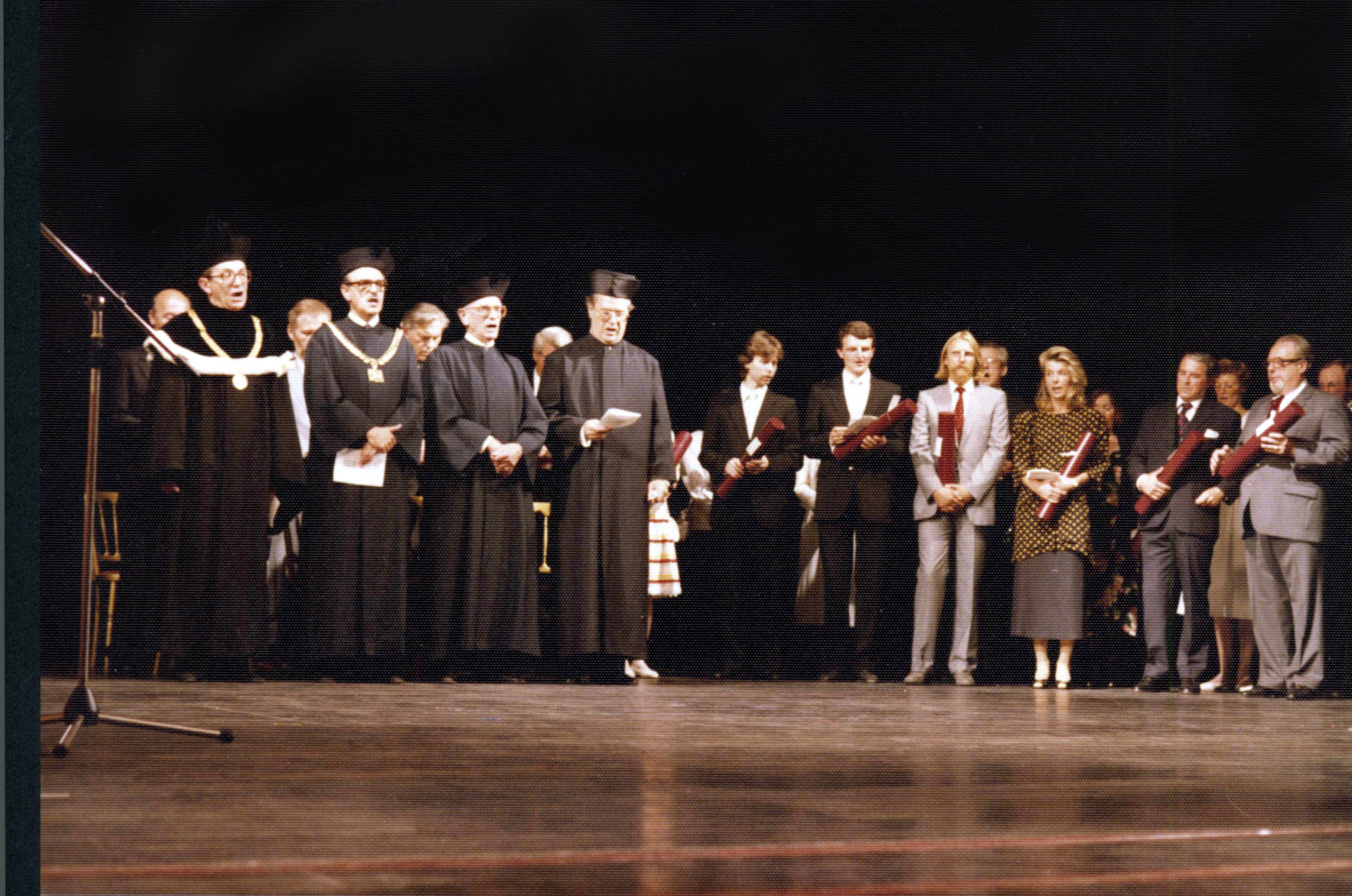

Pictures

Rector Georg Pirckmayer, portrait by Thomas Moog. © mdw-Archive

isa – International Summer Academy. © Stephan Polzer

Rector Scholz at a graduation ceremony, 1986. © Fotostudio Renate Koch

The mdw – University of Music and Performing Arts (1999 – today)

The KUOG was fully implemented at the mdw by 2002. Since then, the mdw has been divided into artistic, scholarly, and pedagogical departments. That same year, passage of the Austrian Universities Act (UG) of 2002 effected a further major change for the future: when it entered into force in 2004, the mdw became a legally autonomous institution.

The KUOG was fully implemented at the mdw by 2002. Since then, the mdw has been divided into artistic, scholarly, and pedagogical departments. That same year, passage of the Austrian Universities Act (UG) of 2002 effected a further major change for the future: when it entered into force in 2004, the mdw became a legally autonomous institution.

Since 2003, all programmes of study have been successively converted to conform to a two-cycle structure (i.e., divided into bachelor’s and master’s degree programmes) as part of the implementation of the Bologna Process.

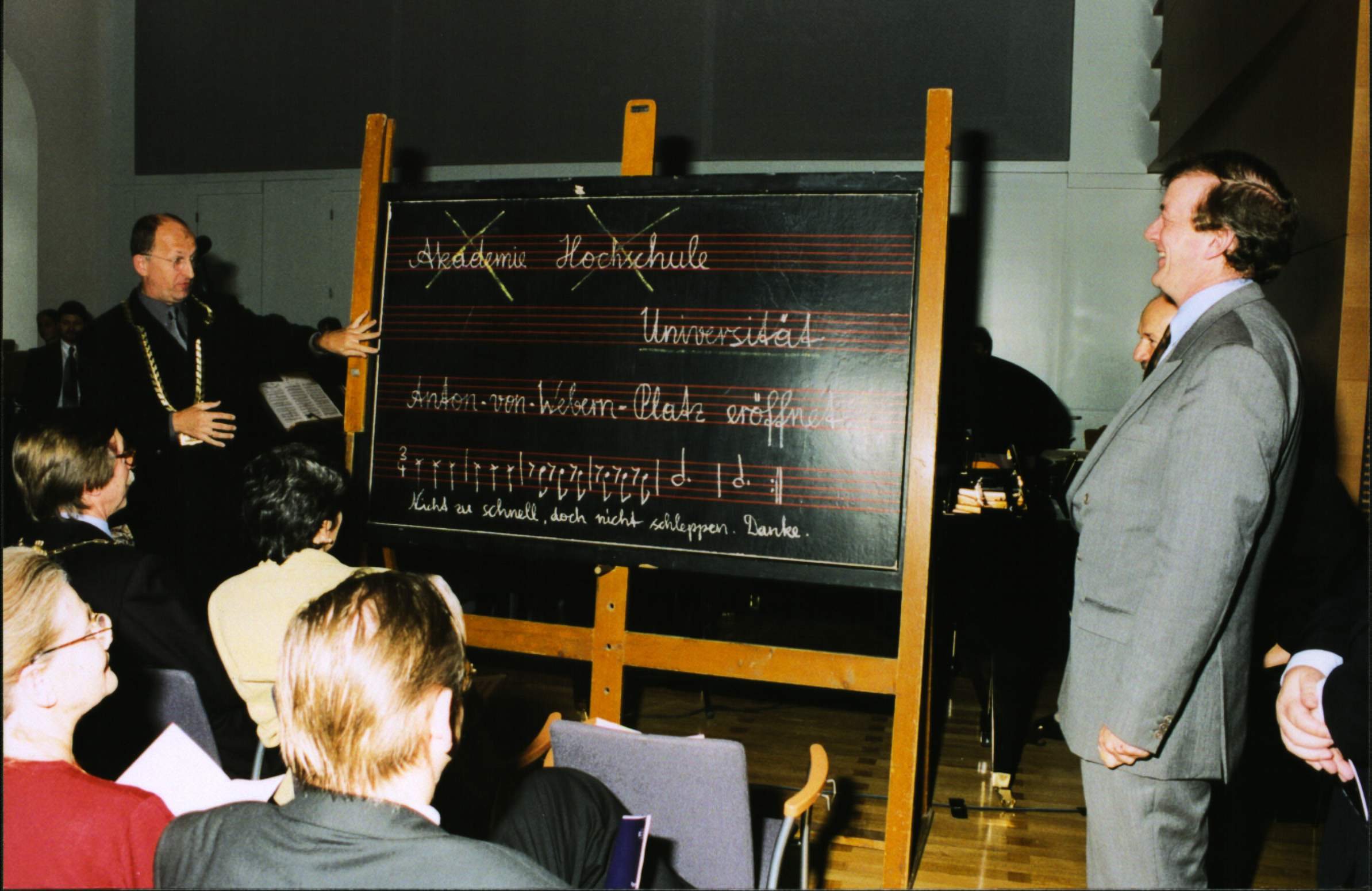

In 1999, following three years of construction and remodelling work, the main building of the mdw Campus at Anton-von-Webern-Platz 1 was ready for use. Since then, numerous other building projects on the Campus have been completed. The most important milestones here have included construction of the film studio (2004), the alteration of several existing structures (2006), construction of the Communication Centre (Mensa) (2012), the new spaces of the University Library (2016), and the construction of the Future Art Lab (2020).

In 1999, following three years of construction and remodelling work, the main building of the mdw Campus at Anton-von-Webern-Platz 1 was ready for use. Since then, numerous other building projects on the Campus have been completed. The most important milestones here have included construction of the film studio (2004), the alteration of several existing structures (2006), construction of the Communication Centre (Mensa) (2012), the new spaces of the University Library (2016), and the construction of the Future Art Lab (2020).

Off-campus projects have included the complete renovation of the building on Seilerstätte from 2010 to 2012. And parallel to the creation of new space for the University, an increase in the number of events has provided students with an enhanced range of opportunities to present themselves in public. A further complete renovation of the main building ran from July 2022 to September 2023, included restoration of the entire roof and the installation of solar panels covering a total of 650 m2 as well as a new building services centre directly below, new ventilation systems for the ground floor concert halls, and partial adaptation and enlargement of the lofts in Wing C as well as in parts of Wings B and D.

Since 2015, Rector Ulrike Sych has been the first woman to head the mdw, and the mdw’s 2017 bicentennial celebrations fell within her first term in office.

Since 2015, Rector Ulrike Sych has been the first woman to head the mdw, and the mdw’s 2017 bicentennial celebrations fell within her first term in office.

Since November 2023 the mdw is part of IN.TUNE: Innovative Universities in Music & Arts in Europe. IN.TUNE is the first European Universities Alliance in the field of music and arts. Together with seven other European universities, the mdw was selected from over 60 applications by the EU Commission.

As of 2024, mdw enrolment stands at around 3,000 students from 70 countries who pursued training in 115 programmes of study and 41 other university programmes.

Pictures

Rector Erwin Ortner and Minister of Education Caspar Einem at the opening of the University campus, 1999. © mdw-Archive

The Future Art Lab, 2020. © Hertha Hurnaus

Rector Ulrike Sych. © Inge Prader

Background Literature

- Annkatrin Babbe, Das Konservatorium der Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde in Wien (1817). In: Freia Hoffmann (Hg.), Handbuch Konservatorien. Institutionelle Musikausbildung im deutschsprachigen Raum des 19. Jahrhunderts, Bd. 1 (Lilienthal 2021) 101–164.

- Lynne Heller, Das Konservatorium für Musik in Wien zwischen bürgerlich-adeligem Mäzenatentum und staatlicher Förderung, In: Michael Fend, Michel Noiray (Hg.), Musical Education in Europe (1770–1914). Compositional, Institutional, and Political Challenges 1 (Berlin 2005) 205–228.

- Lynne Heller, Severin Matiasovits, Erwin Strouhal, Zwischen den Brüchen. Die mdw – Universität für Musik und darstellende Kunst Wien in der Zwischenkriegszeit (Studien zur Geschichte der mdw – Universität für Musik und darstellende Kunst Wien 1, Wien 2018). Zum Buch.

- Lynne Heller, Die Reichshochschule für Musik in Wien 1938–1945 (ungedr. Dissertation Universität Wien 1992).

- Juri Giannini, Maximilian Haas und Erwin Strouhal (Hg.), Eine Institution zwischen Repräsentation und Macht. Die Universität für Musik und darstellende Kunst Wien im Kulturleben des Nationalsozialismus (Musikkontext 7, Wien 2014).

- Lynne Heller, Die Akademie für Musik und darstellende Kunst in Wien 1945–1970. In: Markus Grassl, Reinhard Kapp, Cornelia Szabó-Knotik (Hg.), Anklaenge 2006. Österreichische Musikgeschichte der Nachkriegszeit (Anklaenge. Wiener Jahrbuch für Musikwissenschaft, Wien 2006) 47–72.

- Susanne Prucher, Silvia Herkt, Susanne Kogler, Severin Matiasovits, Erwin Strouhal (Hg.), Auf dem Weg zur Kunstuniversität: das Kunsthochschulorganisationsgesetz von 1970 (Veröffentlichung zur Geschichte des Unversität Mozarteum Salzburg 15, Wien 2021). Zum Buch.