Theresia Ziss

(variants of name: Teresia, Teresa, Theresa, Therese; Zissin, Ziß, Zißin)

(Anna) Theresia Ziss, née Harrer, * 12.4.1700 in Vienna, † 5.11.1777 ibid., music copyist and head of a copyist's workshop in Vienna. Anna Theresia was the daughter of the Viennese court official Heinrich Harrer and his wife Maria Clara. Her family must have maintained a close personal relationship with the imperial family, as Emperor Leopold I and his third wife Eleonore Magdalena served as godparents to Theresia's two eldest siblings. In 1719, Theresia married Johann Andreas (also André or Andreas/Andre Johann) Ziss, who entered imperial service as a music copyist in 1720 at the latest and is listed as a theatrical copyist in the court music records of 1729. Johann Andreas Ziss had some music copyists working for him and in later years was entrusted with the administrative office of concert dispenser in the Vienna Court Music Chapel. After his death in 1755, Theresia Ziss received a pension as "Hof-Concert-Dispensators-Wittwe", e.g. 166 fl. in 1762. Presumably due to the fact that none of her children survived infancy (she gave birth to at least 14 children in the period between 1719 and 1740), Theresia Ziss appointed Maria Rosalia Edle von Ehrenbrunn (c. 1728–1793), director of a cotton factory in Vienna, as her universal heir. Theresia Ziss died on November 5, 1777, of "kaltem Brand" (most probably a type of gangrene) at Kärntnerstrasse no. 1088.

Neither the position of concert dispenser nor that of theatrical copyist was filled after Johann Andreas Ziss' death in 1755. Copying orders for parts and scores were now given to independent copyists, including Theresia Ziss and the scribes working under her direction. Numerous entries in the payment records of the Theatralcassa indicate that Ziss was commissioned to copy sheet music for the German and French theater, for operas and music academies, and somewhat less frequently also for court banquets, chamber music, and balls. Additionally, she had other clients, such as Prince Joseph Adam of Schwarzenberg (1722–1782), who obtained copies of ballet music performed in Vienna from her workshop.

In the corpus of sources examined by CTMV and P&C, the copyist with the code WK71P, identified as Theresia Ziss, is by far the most frequently writing individual. Her workshop delivered at least 83 mostly multi-volume scores to the court between 1759 and 1773. The majority of the copied works are Italian operas, whose world or Vienna premiere at the Theater next to the Burg took place around the time when the copies were made. Only seven scores from Ziss's workshop contain French stage works. Judging by the analyzed sources, she delivered between 11 and 18 elaborately designed scores per year to the court during peak times, but after 1768, the number of orders decreased significantly.

Over the years, Theresia Ziss involved many different assistants in the copying process. In addition to about 20–30 individuals who contributed only occasionally, four copyists collaborated with the workshop leader for an extended period: Together with WK60G and WK72D , Ziss formed a productive trio by 1759/60 at the latest, working simultaneously on the production of score volumes, presumably due to time constraints. During the particularly busy years of 1763–1765, the workshop leader hired new employees. However, a workshop configuration characterized by steady collaboration and shared use of writing materials was maintained only with WK73F and WK71K until the 1770s.

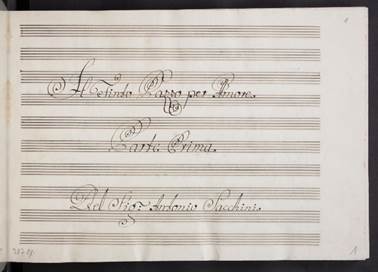

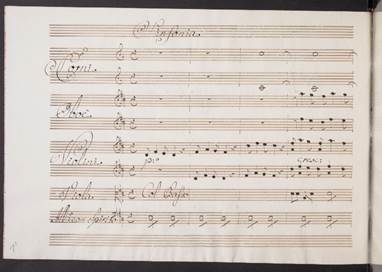

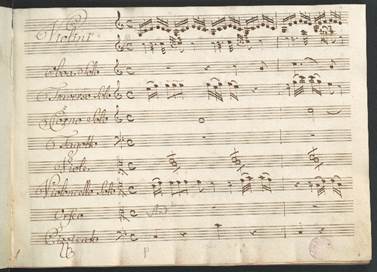

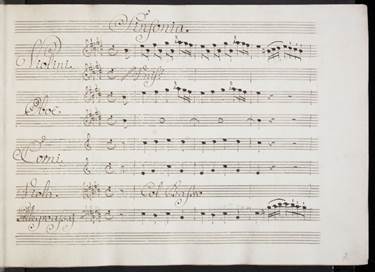

In the manner of a trademark, Theresia Ziss designed the title pages of the score volumes and often wrote the first section of the music part (see Fig. 1–2), occasionally even entire volumes by herself. Beyond contributing to the music text, she made corrections and ensured the consistency of typography, for example by adding missing clefs at the beginning of a page. Her special attention seemed to be on maintaining a uniform script style, as most of the copyists she employed used very similar character forms. Despite the wide range of variation in detail, Ziss's music notation is remarkably consistent both within itself and throughout her entire career as a copyist (see Fig. 3–4). Since the earliest Ziss scores examined in the P&C project (from 1759) already exhibit an extremely uniform handwriting, it can be assumed that she was already an experienced copyist at that time. This strengthens the evidence that she took over the management of her husband's workshop upon his death and had quite likely been a member of the team even before 1755.

Fig. 1 and 2: Title page and first page of Act I of Antonio Sacchini's Il finto pazzo per amore, written by Theresia Ziss in 1771 (A-Wn Mus.Hs.10070/1, f. 1r–v )

Fig. 3 and 4: First pages of C. W. Gluck's Orfeo and Alessandro Felici's L'amor soldato, written by Theresia Ziss in 1762 and 1773 (A-Wn Mus.Hs.17783/2, f. 1r and Mus.Hs.18059/1, f. 2r)

For a more detailed version of this article and a comprehensive list of primary sources, see Hornbachner 2024

Literature

Lawrence Bennett, "A Little-Known Collection of Early Eighteenth-Century Vocal Music at Schloss Elisabethenburg, Meiningen," in: Fontes Artis Musicae 48/3 (2001), 250–302.

Bruce Alan Brown, „Wiener Ballette im Schwarzenbergischen Archiv zu Cesky Krumlov," in: Gabriele Buschmeier / Klaus Hortschansky (eds.), Tanzdramen, Opéra-comique: Kolloquiumsbericht der Gluck-GA (Kassel: Bärenreiter, 2000), 9–34.

Bruce Alan Brown, Gluck and the French Theatre in Vienna (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1991).

Bruce Alan Brown, "Durazzo, Duni and the Frontispice to Orfeo ed Euridice," in: Studies in Eighteenth-Century Culture 19 (1989), 71–97.

Thomas A. Denny, „Wiener Quellen zu Glucks 'Reform'-Opern: Datierung und Bewertung," in: Irene Brandenburg / Gerhard Croll (eds.), Beiträge zur Wiener Gluck-überlieferung (Kassel: Bärenreiter, 2001), 9–72.

Dexter Edge, Mozart's Viennese copyists, Ph.D diss Univ. of Southern California 2001, Ann Arbor, UMI.

Dexter Edge, "Viennese music copyists and the transmission of music in the eighteenth century," in: Revue de Musicologie 84 (1998), 298–304.

Hannelore Gericke, Der Wiener Musikalienhandel von 1700 bis 1778 (Graz: Böhlau, 1960).

Christoph Willibald Gluck, Ballettmusiken (= Christoph Willibald Gluck. Sämtliche Werke II/3), ed. by Irene Brandenburg with a foreword by Bruce Alan Brown (Kassel: Bärenreiter 2022).

Maren Goltz, Musiker-Lexikon des Herzogtums Sachsen-Meiningen (1680–1918) (Meiningen 32012).

Maren Goltz, Die Wiener Libretti-Sammlung des Herzog Anton Ulrich von Sachsen-Meiningen (Meiningen 2008).

Christiane Maria Hornbachner / Constanze Marie Köhn, "Watermarks in Viennese Opera Scores: Toward a Comprehensive Database of Music Paper 1760–1775," in: Patricia Engel et al. (eds.), Artists' Paper: A Case in Paper History (Horn: Berger Verlag, 2023), 484–502.

Adolf Koczirz, „Exzerpte aus den Hofmusikakten des Wiener Hofkammerarchivs," in: Studien zur Musikwissenschaft 1 (1913), 278–303.

Ludwig von Köchel, Die Kaiserliche Hof-Musikkapelle in Wien von 1543 bis 1867. Nach urkundlichen Forschungen (Wien: Beck, 1869).

Constanze Marie Köhn, "Collaborative work processes in Viennese copyist workshops," Musicologica Austriaca: Journal for Austrian Music Studies [in prep.].

Josef-Horst Lederer, „'[…] von denen eingangs benannten Supplicanten unter eines jeden eigenen Hand:Unterschrift Copiaturen anbegehret.': Vier Eingaben zur Nachbesetzung einer Kopistenstelle am Wiener Hof aus dem Jahre 1755," in: Irene Brandenburg / Gerhard Croll (eds.), Beiträge zur Wiener Gluck-überlieferung (Kassel: Bärenreiter, 2001), 73–94.

Emilia Pelliccia, "Layers of Meaning. Salieri's 'Locandiera' 1773 and 1782", Musicologica Austriaca: Journal for Austrian Music Studies [in prep.].

Jiří Záloha, „Hudební zivot na dvore knízat ze Schwarzenberku v 18. století," in: Hudební věda 24/1 (1987), 43–62.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.21939/ns98qc

License: CCBY-SA

Last edited: 31.07.2024

How to cite:

Christiane Maria Hornbachner, "Theresia Ziss", Paper and Copyists in Viennese Opera Scores / Copyists / Theresia Ziss,

last edited 31.07.2024,

https://doi.org/10.21939/ns98qc (retrieved: 2025/12/14)