A turbulent history with unexpected continuities

In 2019, the Vienna State Opera will be celebrating 150 years of existence—and in anticipation of this jubilee, a team of researchers has brought to light new findings on this institution’s reciprocal relationships with the political world.

The Vienna State Opera, formerly the Imperial Court Opera, is a central locus of Austria’s cultural self-understanding and cultural memory, and from the very beginning, its story progressed hand-in-hand with Viennese and national political developments. In order to portray these interrelationships in their diverse aspects, three prominent institutions—the Institute of Research and Art (IWK) and the Department of Musicology and Performance Studies at the mdw, and the Institute of Contemporary History at the University of Vienna—joined forces to conduct a FWF-sponsored research project.

In light of multi-layered contexts and the long period to be covered, this project focused on a sequence of five exemplary transitional phases that historical analysis suggested would be particularly relevant. And indeed, the team’s research on these five selected phases of Viennese operatic history produced findings so abundant that they can be sketched out but roughly in the space available here.

Their Phase 1 encompassed the period during which the new opera house was built and during which the so-called Ringstraße culture arose against the backdrop of liberal dominance in Vienna city politics, the compromise with Hungary, the Vienna World Exposition, and the Panic of 1873 along with a cholera epidemic that same year. The new opera house on the Ring was hotly debated but simultaneously a major site of this culture’s artistic expression and discourse. Aspects of the then-prominent discussion on (national) identity were examined in light of two significant works from the Viennese operatic repertoire of this period: Richard Wagner’s Lohengrin and Carl Goldmark’s Die Königin von Saba.

Phase 2 was focused above all on 1897, the year in which Karl Lueger became mayor. That same year, the “Badeni Riots” shook Prague, Vienna, and other cities of the empire. Set off by a language ordinance for Bohemia and Moravia that had been badly prepared from a political standpoint, this turmoil pushed the conflict between Austria-Hungary’s many nationalities into anew phase that was to prove critical for the empire as a whole. That year also saw Gustav Mahler became Director of the Court Opera. All these events were then reflected by the reception of the Court Opera’s programming of the supposed “national opera” Dalibor by Bedich Smetana.

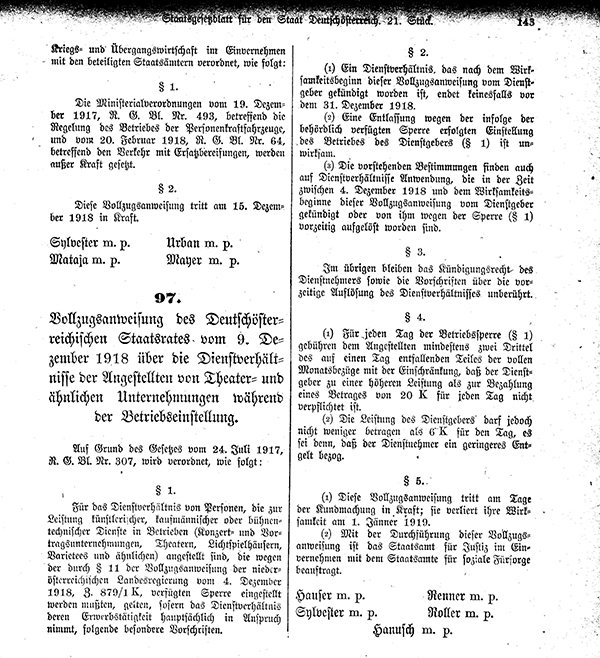

Phase 3 was embodied by the (by that time) State Opera’s history during the young republic of the 1920s. The former Court Opera represented a significant financial burden for the struggling new Austrian state, but a feeling of responsibility for “Austrian music” ultimately led to the decision to keep it running. Due to budgetary constraints, programming henceforth focused on performances of old, well-known pieces by “the masters” rather than new works. Operas by Richard Strauss (who had long had close ties to the institution and then became its director in 1924) were the object of intense public controversy and also found their way into political discussions, since they were tantamount to a continuation of the elitist music theatre culture of the pre-World War One era. Here, the researchers took Strauss’s opera Die Frau ohne Schatten and his ballet Schlagobers as case studies. In the inner workings of the opera itself, however, there was no substantial break—and thus no entirely new beginning. The change in political systems was felt primarily in the legal sense, as well as in terms of new relevant governmental counterparts and, of course, the institution’s new name.

At the same time, the attempts to establish an institutionally wellanchored

city music policy by Vienna’s socialist city government—

evident since 1905, at the latest, with the initiation of the Worker’s

Symphony Concerts—were geared more toward evolution

than revolution, focusing intensively on artistic heritage and its

appropriation. So in that sphere, as well, efforts towards continuity

remained dominant despite the great political upheavals.

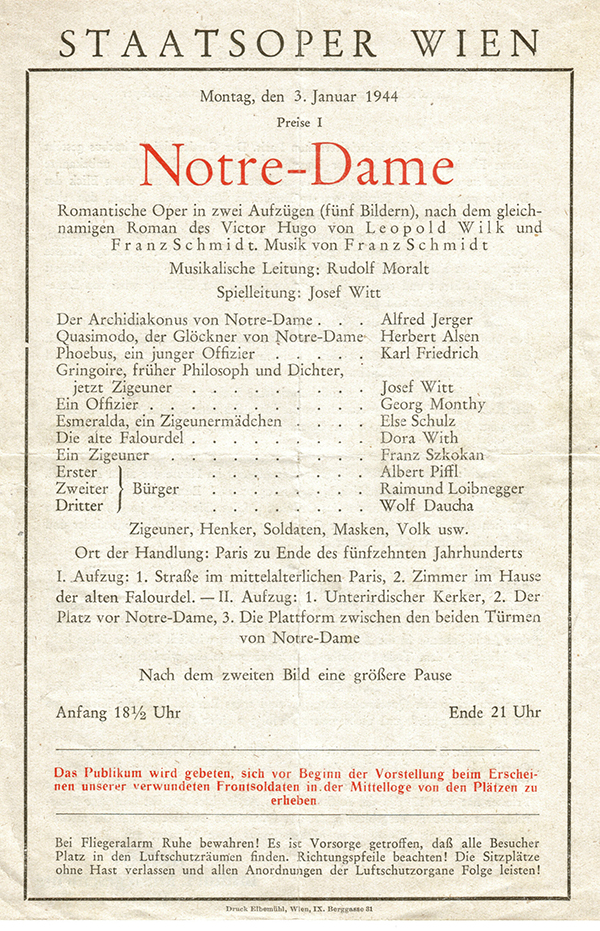

1928 witnessed protests against Ernst Krenek’s opera Jonny spielt auf that took the ongoing discussions about opera to a new level of intensity. Among other things, they were the target of Vienna’s first National Socialist-led mass demonstration. So the 1930s and ’40s were chosen as Phase 4, with the project examining how opera related to the dictatorships of that period. This 1934–1945 phase is portrayed with reference to Ernst Krenek’s actually quite establishment-friendly—but unrealised—opera Karl V., Franz Lehárs triumph with Giuditta, and Rudolf Wagner-Régeny’s “scandalous opera” Johanna Balk. The questions pursued by the researchers with regard to this period address matters including the relevance of the specifically “Viennese” policy of National Socialist Gauleiter and Reich Governor Baldur von Schirach.

The project’s Phase 5, finally, was the period immediately following the Second World War. From the very beginning, the cultural sphere of those years was characterised by the justice system’s efforts to deal with National Socialist crimes. The documents of the special commission set up to this end represented an important source for the project team, who were the first to subject them to scholarly evaluation. At the same time, the image presented by Viennese opera to the outside world was of special significance. And particularly in preparation for the State Opera building’s reopening (following heavy damage in the war’s final days) and as a symbol of the city and the nation, opera also became a medium via which contact was re-established with emigrant circles in the USA—and this aspect of recent history, which has seen little study up to now, was looked at by the researchers as a secondary Phase 5 emphasis.

It should not come as a surprise that the interdisciplinary project team devoted a considerable portion of its efforts to hunting down, surveying, and studying relevant archival material. Underthe leadership of Christian Glanz, deputy head of the mdw’s Department of Musicology and Performance Studies, team members Carolin Bahr and Angelika Silberbauer (musicology), Tamara Ehs (political science), and Fritz Trümpi (contemporary history) spent three years researching for the project Eine politische Geschichte der Oper in Wien 1869–1955 [A Political History of Opera in Vienna 1869–1955], with contemporary historian Oliver Rathkolb serving as a project partner.

With this project and its findings, the research team proceeded very much in keeping with present trends (the Munich State Opera is likewise currently researching its political past), and they are now also actively involved in the preparations for the Vienna State Opera’s jubilee year of 2019. Together with earlier research works on reception history, their findings will make a significant contribution to the further development of the narrative concerning a highly relevant area of Austrian arts and cultural policy.

Texts and materials on this project’s findings can be accessed at: www.mdw.ac.at/imi/operapolitics