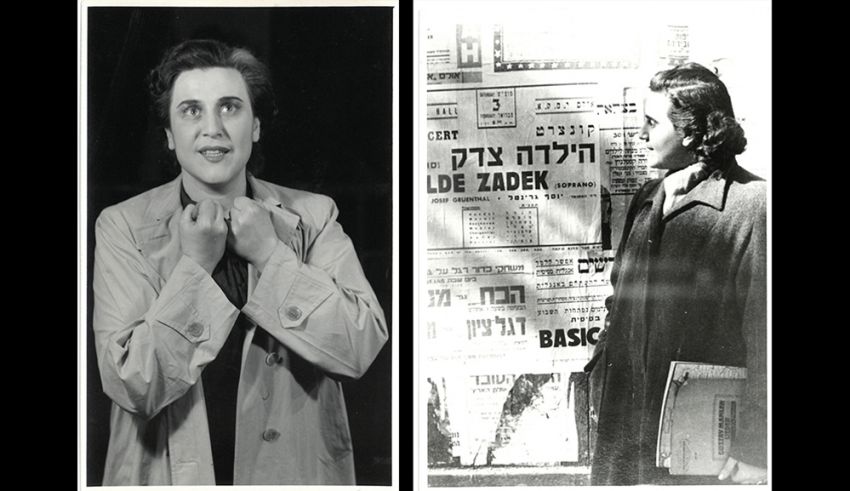

At age 29 and with no rehearsal, she made her debut at the Vienna State Opera as Aida – and as the first Jew to perform there following World War Two. The soprano, voice teacher, and career-builder Hilde Zadek will be celebrating her 100th birthday on 15 December of this year.

©provided

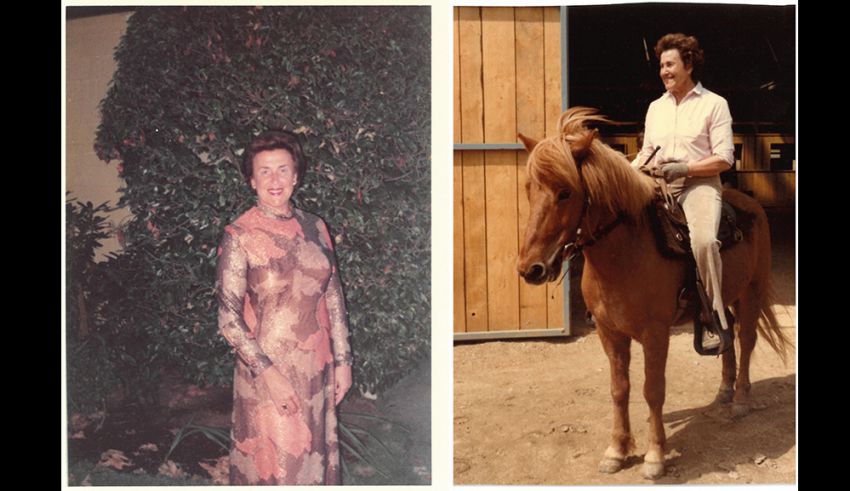

Even today, she still feels connected with the Marschallin from Richard Strauss’s Rosenkavalier – a role she sang in over 100 performances worldwide – because this character is symbolic of constant development, says Hilde Zadek. And when Zadek raises her voice, one thinks of the Marschallin’s “Neapolitan general” exclamation from the opera – but not of the fact that, in just a few months, she’ll have been in this world for 100 years. Zadek was always guided by just one urge: to sing. “For me, singing wasn’t just an occupation – it was a calling.” She consistently drew her feel for music from the overall whole, which she describes as consisting of giving and taking. “And we take from the past as least as much as we do from the present,” adds Zadek, whose own past reveals both wonders vand horrors.

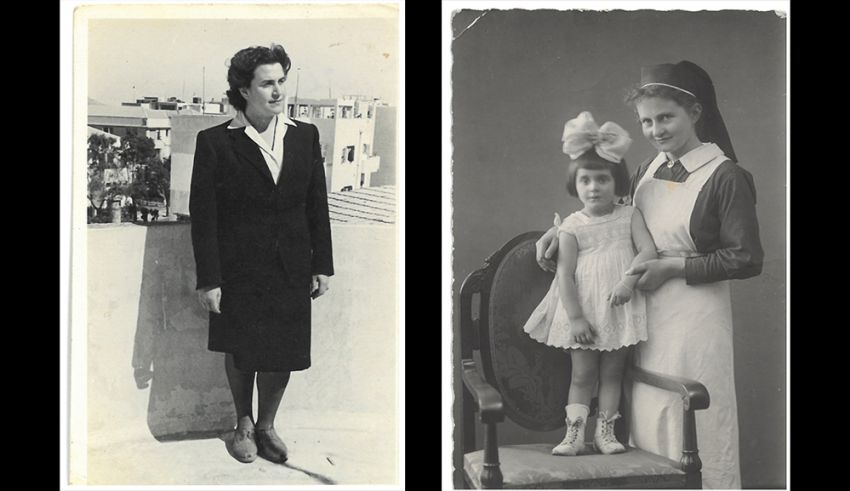

It was quite early in life that Zadek, born in 1917 as the daughter of a Jewish family in Bromberg/Posen in present-day Poland, was forced to defend herself against the rising barbarism around her. And that she did – quite actively, even answering the anti-Semitic slurs of one girl in her school with her fists. After that incident, with Zadek being a teenager in times that were dangerous to begin with, nobody could guarantee her survival.

So she emigrated to Palestine and was accepted as an intern at a children’s home, where she had to live in a room together with thirteen three-year-olds. Years later, Zadek would involuntarily think back to the food there, above all, which consisted of nothing but oatmeal and semolina porridge. She knew that she didn’t want to stay at that facility, so she found a position as an infant care nurse in a Jerusalem hospital. One of the women working there as a doctor, who also led the local conservatory, proved to be Zadek’s ticket into Jerusalem’s musical life.

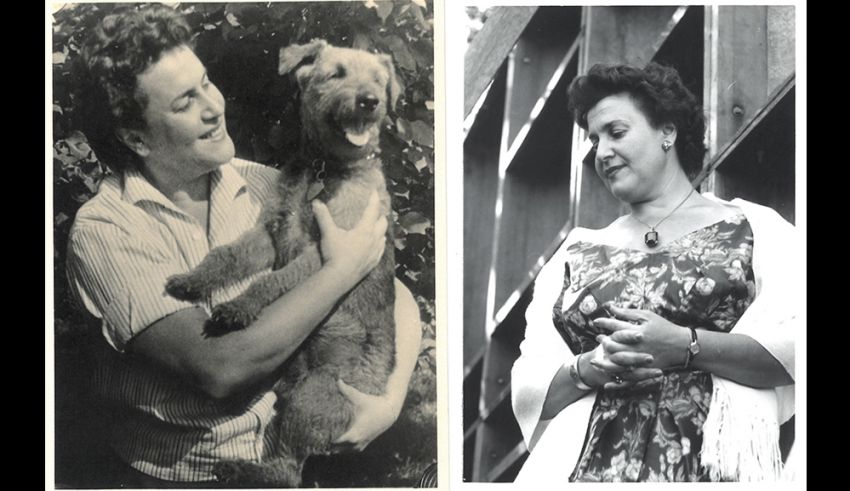

During this period, the National Socialists sent Zadek’s father to Sachsenhausen concentration camp. But young Hilde, working from a distance, managed to organise his release and her parents’ emigration – under the condition that they leave behind everything they owned. 1940 saw the family found one of the first children’s shoe stores in Jerusalem, where Zadek would work for five years to finance her study of voice at the conservatory in Jerusalem. Back then, it had been anything but a given that she would ever be able to raise her voice in song again. For her voice had fallen silent during her initial years as an emigre. Only upon being reunited with her family did Hilde Zadek find her way back to music. She then managed to obtain a scholarship in Zurich, where she worked as an au pair (caring for the future stage directors Thomas and Matthias Langhoff) in order to earn her keep and pay for her lessons.

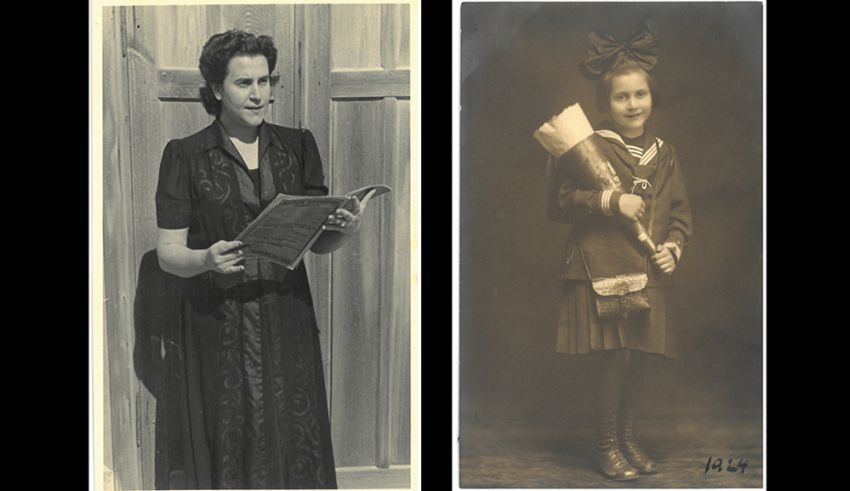

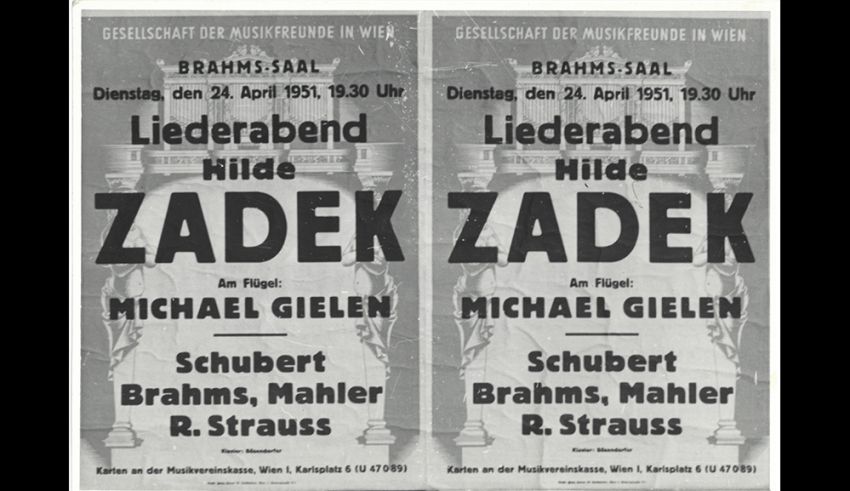

Then, at a student recital, the young soprano caught the attention of Viennese impresario Franz Salmhofer, who brought her to Vienna. Her first appearance was to be in the title role of Verdi’s Aida. Knowing neither Italian nor the role, she accepted and prepared this formidable amount of material within just a few days – after which she even managed to impress conductor Josef Krips.

She held no grudges against an audience that, just a few years before, had belonged to a regime that had threatened her life. “I just decided to love the Viennese audience; otherwise, I wouldn’t have been able to sing for them,” she explains. But she didn’t shy away from possible conflicts with conductors who had been regime loyalists. “Karl Böhm was a Nazi. And there was no question that he wasn’t particularly fond of Jews,” says Zadek, though she hastens to emphasise that, in art, private difficulties need to disappear. And with one exception, which came in the form of a slip of paper on her car’s windshield after a performance of Richard Wagner’s Walküre, she didn’t feel subject to any anti-Semitic aggression. “I think that the audience in Vienna accepted me absolutely, including my Jewishness,” she concludes.

Zadek student Georg Nigl, a world-class baritone, describes her as a “once-in-a-century occurrence in the best possible sense.” And Zadek, as such, launched her second once-in-a-century career in the 1960s as a voice teacher at Vienna City Conservatory. Alongside Nigl, her students included Adrienne Pieczonka, Alfred Sramek, and Georg Tichy. As well as Linda Plech, who remembers a teacher who demanded everything of herself and her students. Nigl, who himself now teaches voice in Stuttgart, knows just how strenuous teaching can be. “When you teach young singers, you can never just lean back and listen. Your attention is required constantly. So it’s unbelievable how, following a master class, she’d still have the most energy of us all,” he remarks. Unlike some big-name colleagues, “Zadek really did adapt herself to each student and try to bring out his or her individual personality. And though she’s experienced human beings’ darkest sides, she’s infinitely generous and always open to new things. She even learned to use the Internet at age 92,” recalls Nigl. And what’s more, many of her former students went on to become professors themselves, including Gertraud Berker Schmid, Maria Venuti, Margit Fleischmann, Margarete Jungen, and Georg Nigl.

In the opera business, as well, Zadek the singer – who was once part of the State Opera’s legendary Vienna Mozart Ensemble –

always maintained a realistic view of current developments. And in 1998, she founded a competition under her own name. In doing so, she sought to “give beginners the chance to introduce themselves to the world, compare themselves to each other, and improve,” says Zadek. When asked about the fact that many young singers are unable to withstand today’s tough opera business, she responds drily: “That’s the way it’s always been. And it’s like that among animals, too. The strongest ones make it, while the weakest fall by the wayside. And that’s just fine.” Zadek goes on to disagree with people who view themselves as victims of marketing: “Music’s always been a business – think of the minnesingers back in medieval times! What’s important is what you make of that business.” On Anna Netrebko, for example, today’s most prominent example of operatic stardom, Zadek says that she likes how “her voice is clear as a bell. And she’s honest. If there were more personalities like Netrebko doing opera, they could be wonderfully marketed,” says Zadek with the realism of Strauss’s Marschallin.

But unlike the Marschallin, she doesn’t think for a moment of halting time: “I think it’s wonderful to turn 100. I’d even be willing to go to 200. As long as you have the feeling of being creatively involved in your times, longevity is wonderful thing.”