expulsion, persecution, continuity, and new arrivals

A jubilee year should not be allowed to go by without also speaking about those phases of an institution’s own past that said institution might be more comfortable overlooking; after all, a closer look does tend to indicate the fragility of educational institutions’ usual proud professions of adherence to certain values—values like supporting people in realising their highest potential, upholding traditions, and implementing new, pioneering measures. The persecution and expulsion of instructors and students that took place during the National Socialist period speaks a different language indeed: under the National Socialist regime, people were branded as “different” and, as a consequence, lost nothing less than their right to exist. The process by which this occurred, which has already been researched by way of a diverse range of projects at the mdw, is now being paid further attention as part of the initiative spiel|mach|t|raum – frauen* an der mdw 1817–2017 with a concerted focus on women*, without ignoring those men who likewise fell victim to the destructive denigration of human beings on account of—as we would put it today—characteristics that were first constructed and then attributed to them. Related questions to be dealt with include: Who was allowed to stay? Who was newly admitted during this period? And—last but not least—what impact did all this have at the student level?

Source: mdw Archives

The process of “cleansing the artistic temple” of “Jewish influence”, as it was formulated in the 16 March 1938 issue of the Nazi party publication Völkischer Beobachter, progressed swiftly at the State Academy, the forerunner of today’s mdw. All existing contracts were declared null and void on 30 May 1938, and the selective non-renewal of contracts conveniently eliminated the regime’s need to actually fire politically unacceptable civil servants in accordance with the Neuordnung des österreichischen Berufsbeamtentums [Reorganisation of Austria’s Professional Civil Service] that entered force on 31 May 1938. Lynne Heller writes that 26 % of the teaching staff were let go on “racial grounds” (Heller 1992), and when one adds political and other reasons, the figure rises to total 50 % (www.mdw.ac.at/geschichte).

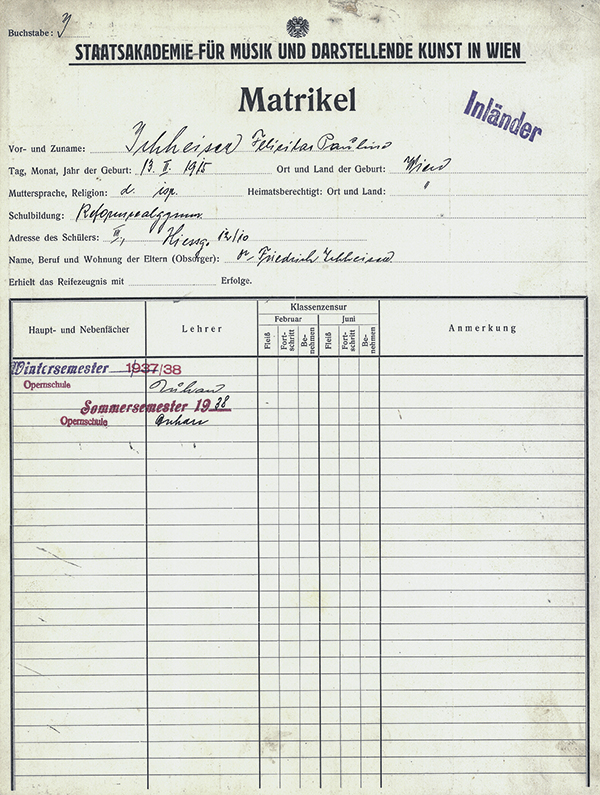

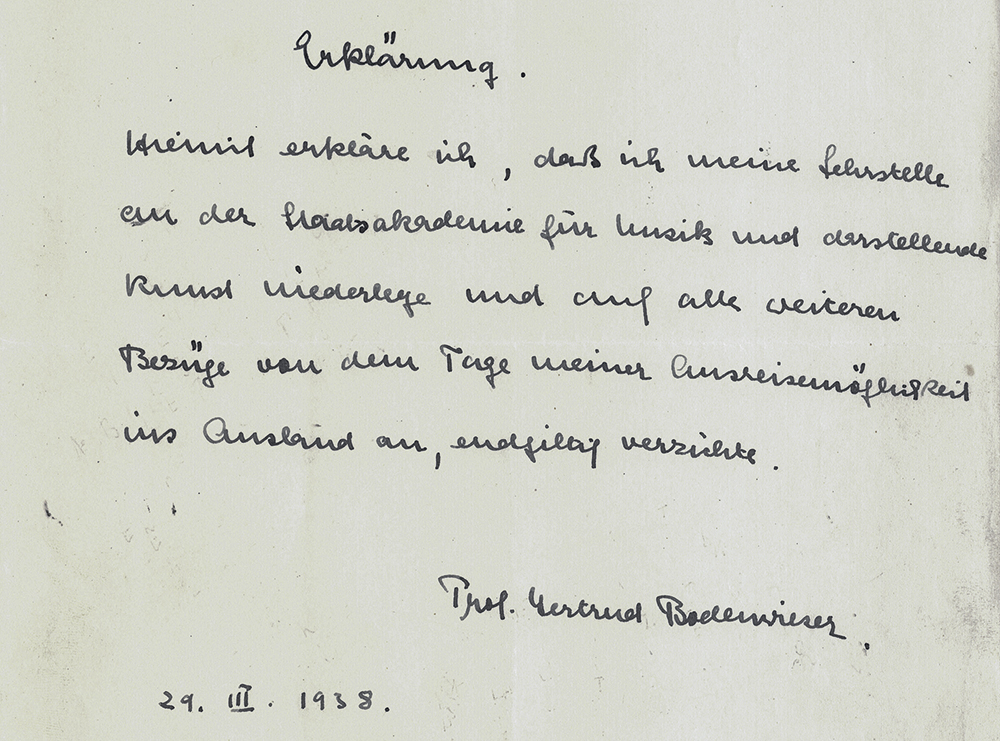

One of the best-known individuals who fell victim to National Socialist persecution was Gertrud Bodenwieser-Rosenthal, a dancer, choreographer, dancing teacher, and pioneer of expressive dance who had been hired by the Academy in 1920. Back then, her ballet-derived style of dance had met with great audience enthusiasm. But in 1938, together with several of her students, she was forced to flee from the National Socialist regime—first ending up in Colombia and, later on, in Australia.

A further victim was Erna Kremer. A pianist and herself a graduate of the State Academy, Kremer had been hired as an instructor in 1934. She was murdered at the Maly Trostenets extermination camp in 1942.

Source: Kunstnachrichten. Information des Arts. Organ für Musik, Theater, Literatur, Kunst und Wissen, special issue: Festausgabe der Staatsakademie für Musik und darstellende Kunst zum Internationalen Musikwettbewerb 1937 [Celebratory Publication of the State Academy of Music and Performing Arts for the International Music Competition of 1937], edited by Ing. Karl Oeschler, [Vienna 1937], 34, mdw Archives

The national socialist regime’s persecution of individuals defined as Jewish according to the Nuremberg Laws as well as people of other political convictions also affected many students (see Posch/Ingrisch/Dressl 2008). This can be clearly seen in the enrolment statistics: while 531 female students and 479 male students had been enrolled during the winter semester of 1938/39, these figures had dropped to 326 female students and 379 male students by the winter semester of 1938/39. It is noteworthy that more women were affected than men. The names of all the expelled students are commemorated in a new contribution to the website spiel|mach|t|raum, but the further courses taken by many of their lives still lie in the dark. Present knowledge indicates that two of the male students and two of the female students did not survive the Holocaust.

The year 1938 was also a year of new admissions to the State Academy of Music and Performing Arts, including a considerable number of women—particularly in the field of dance. A few examples: Tonia Wojtek-Goedecke, who held posts including as a specialist advisor to the Reich Theatre Chamber, was the candidate to head the Department of Dance favoured by Franz Schütz, the State Academy’s rector, in 1938. Wojtek- Goedecke was placed on involuntary leave in 1945 and fired in 1946. There were also a number of women in the fields of voice, piano, and piano accompaniment for whom this period represented a career opportunity. This was the case above all in the field of music education (Schmidt 1986). Guitarist Luise Walker, whose married name was Heysek, was the first woman to teach her instrument to future music educators and performance majors. She was hired by the Academy in 1940 and, post-1945, she remained all the way up to her retirement in 1980.

Remembering can be a challenge. For ultimately, what always remains is the question as to our responsibility in the present, the question as to the standards according to which we think and act—in the arts, in scholarship, in teaching, and in shaping our institution.

A detailed article on this topic will be published on 10 October 2017 at the website spiel|mach|t|raum – frauen* an der mdw 1817–2017:

Literature

- Lynne Heller, Die Reichshochschule für Musik in Wien 1938–1945, Dissertation, University of Vienna 1992.

- Herbert Posch, Doris Ingrisch, Gert Dressel, “Anschluß” und Ausschluss 1938. Vertriebene und verbliebene Studierende der Universität Wien (Emigration – Exil – Kontinuität. Schriften zur Wissenschaftsgeschichte 8) Münster/Vienna 2008.

- Hans-Christian Schmidt, Handbuch der Musikpädagogik, 4 vols., Kassel 1986