Even in music, the gender gap is finally beginning to close … at least here and there. Good news first, or bad?

Let’s start with the good news: in the broad field of contemporary music, the presence and prominence of woman composers, improvisers, and performers has increased during recent years in a way that’s difficult to miss. A cursory survey of festival and ensemble programming from Darmstadt to Donaueschingen and on to Vienna shows a rapidly rising female quotient. Among the new works being programmed for the festival Wien Modern, for example, the share of music composed by women was 45% in 2018 and will be 37% in 2019.¹ 57 different woman composers and improvisers can be found in the Wien Modern 2019 programme alone.² So in the present day and age, those denizens of the contemporary music world who persist in saying that they “unfortunately didn’t find any interesting woman composers (improvisers, performers)” reveal themselves to be regrettably ill-informed and urgently in need of an update. An update, by the way, that pays off in spades—but more on that later.

And now, the bad news: even though the contemporary music scene does have an easier time with all this than the budgetarily far-larger realm of traditional classical music, which is notorious for its “sexism problem” (Süddeutsche Zeitung 2017³), gender equality—even in the avant-garde—is still a long ways off. One ratio that remains particularly lopsided, only slightly less so than in classical music, is between female and male conductors. And the share of woman composers, for its part, definitely can still be increased.

The 20th-century development of contemporary music began as if there simply weren’t any women in the world: at the Donaueschingen Festival, the 1921–1960 period saw not a single woman composer listed; between 1961 and 1980, there were a total of 7 (below 3%), and over the following decades this figure amounted to 11 (8.73%), 25 (10.16%), and 36 (12.5%). The 2011–2018 period included 58 women (22%), with this figure most recently rising to a total of 16 composers and improvisers for 33% in 2018. At the Darmstadt International Summer Courses for New Music, the 1946–1972 period saw a total of 10 works by woman composers performed, with a maximum of one per year (0–2%) and the first being heard only in 1949. From 1974 to 1982, it was 12 works, 1984–1992 included 110 (5–12% per year), 1994–2003 included 71 (5–17%), 2004–2012 included 95 (9–19%), and the figure for 2014—a year with 46 woman composers represented—was 18%. Since the establishment of “GRID – Gender Research in Darmstadt”⁴ in 2016, the curve here—along with the associated debate—has picked up speed considerably.

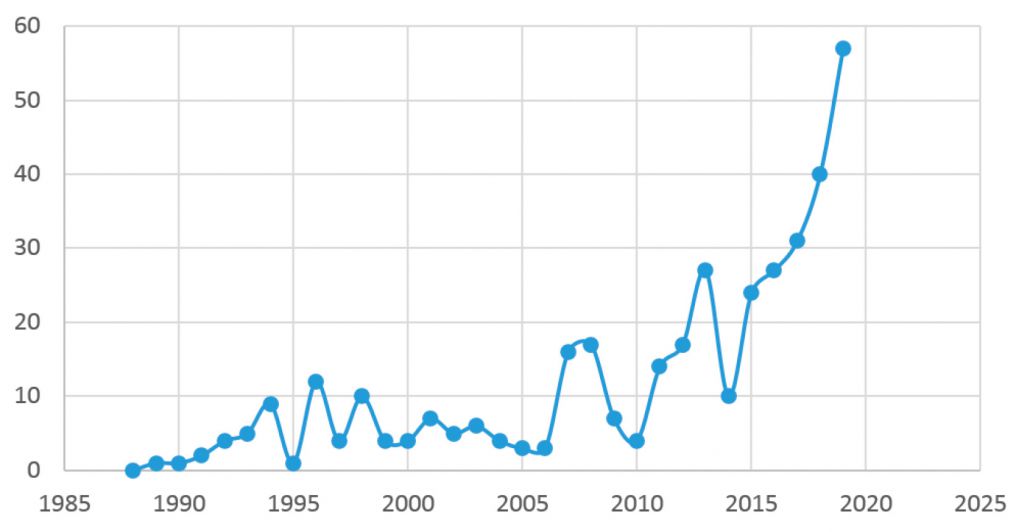

The festival Wien Modern, in its founding year of 1988, launched its public activities without a single woman composer on the programme, and the following year included only Sofia Gubaidulina. These days, something like that would be considered somewhere between absurd and scandalous at Wien Modern, in Darmstadt, or in Donaueschingen—but one still does occasionally see other major music festivals programme just one woman composer as a fig leaf of sorts. One can therefore say that numerous small and avant-garde platforms have woken up by now, but in some instances that are situated a bit closer to the classical mainstream, this rapid development has gone entirely unnoticed.

Some thoughts about what might currently underlie the success seen in contemporary music…

Coming back to the good news: What effect has the growing share of woman composers and performers out there had on the avant-garde festivals mentioned above? For one thing, I’d suppose that the gender balance in audiences and among up-and-coming composers and performers is beginning to play a role—and in light of the current shares of women in audiences (51% of Wien Modern attendees) and at universities of music (55% of mdw students), the consistently marginal presence of woman composers and conductors prior to the beginning of the 21st century would seem an odd misunderstanding that needs to finally be eliminated.

The common present-day approach of thinking in networks and engaging in ever more diverse and decentralised exchange would suggest that an idea of Internet pioneer John Gilmore —“The Net interprets censorship as damage and routes around it.”—might be something we really should take to heart. And in actual fact, the contemporary and experimental music fields have been quicker than classical music to show that, to put it with a bit of pathos, either the “strictly guarded fortresses of high culture” are opening up, being updated, and diversifying, or more and more alternatives to them are being created. Which means that in lieu of resigning themselves to further decades of frustrated waiting for hidebound concert and opera venues, festivals, and ensembles to open up a bit, more and more artists are taking matters into their own hands by forming their own platforms. In Austria, examples of this over the past 15 years have included Freifeld, Fraufeld, Platypus, Schallfeld, Black Page Orchestra, Velak V:NM, Reheat, Der blöde dritte Mittwoch, and numerous other initiatives—with more or less all such independent initiatives far exceeding the share of women represented at any of the established opera houses one might care to investigate.

“Patriarchal structures have inscribed themselves deeply on the world of artistic work,” ascertained Olaf Zimmermann in a 2016 report published by the German Cultural Council.⁵ And music, for its part, may indeed traditionally exhibit particularly extreme imbalances compared with other art forms—but in the avant-garde realm, at least, word does seem to have gotten out that there are, in fact, alternatives to old patriarchal patterns … and that those patterns themselves can sometimes be quite annoying. “Conducting really is a very strange profession,” said Heinz Holliger a few years ago in one such instance, shaking his head upon sighting a classical music poster showing a podium star with an ecstatically imperious expression on his face. Even so, “the profession had become a lot more female,” ⁶ said Emmanuel Krivine recently, pointing out—among other things—the reduced prevalence of and tolerance for authoritarian behaviour.

Greater public attention for new formats and experiments, the growing role of collective work and flat hierarchies, the gradual shift from works to processes—these and other increasingly palpable changes in contemporary music have entered into mutual interplay with increased artistic participation on the part of women. And not unimportantly, the scene’s development has become quite a bit more dynamic thanks to the large number of interesting woman composers and performers. One sees, then, that woman composers are driving forward the aesthetic development of new music in myriad ways, for which reason it would make zero sense to compile programmes without them.

Some thoughts on what might also help in the classical music field…

The improved gender balance among performers over the past few decades has been good for the classical music business. So what might be helpful in terms of composers and conductors? If programmers who have to focus on the standard classical music repertoire consistently have problems “finding interesting works by woman composers” while those who commission or programme new works can now rejoice in having an abundance of material to choose from, one angle of attack would seem fairly obvious: to include more contemporary music in classical programming. To commission more new works. And perhaps also to simply check, before declaring a programme finished, whether one might have inadvertently neglected to involve woman composers and conductors—much like one checks to see whether a gas stove is turned off before leaving one’s home.

fifty-fifty in 2030. Gender equality in music, ten years from now

Footnotes

- In 2018, Wien Modern programmed 104 new works (world or territorial premières), of which 55% were by male composers, 32% were by female composers, and 13% were by male-female composing teams. In 2019, Wien Modern is planning to present 109 new works, of which 63% are by male composers, 28% are by female composers, and 9% are by male-female composing teams.

- This figure from Wien Modern’s 2019 programme planning corresponds with the sum total of all occurrences of woman composers in Wien Modern’s programmes between 1988 and 2000 (with woman composers who appeared multiple times, in contrast to 2019, being counted once each time). The figures from the 1988–2015 period, including those in the chart, are based on a fairly cursory check of Wien Modern’s 30th anniversary festival catalogue of 2017; more detailed research would unquestionably produce more precise data.

- Simon Tönies: “Die klassische Musik hat ein Sexismusproblem”, Süddeutsche Zeitung, 11 Jan. 2017, online at: https://www.sueddeutsche.de/kultur/gender-debatte-die-geschlechterkluft-ist-tief-1.3325426

- Ashley Fure: GRID: Gender Research in Darmstadt. A 2016 HISTORAGE Project Funded by the Goethe Institute, online at: https://griddarmstadt.files.wordpress.com/2016/08/grid_gender_research_in_darmstadt.pdf; cf. https://griddarmstadt.wordpress.com

- Olaf Zimmermann: “Diversität hebt die künstlerische Qualität: Geschlechtergerechtigkeit im Kulturbereich,” Gabriele Schulz, Carolin Ries, Olaf Zimmermann: Frauen in Kultur und Medien. Ein Überblick über aktuelle Tendenzen, Entwicklungen und Lösungsvorschläge. German Cultural Council, 2016, online at: https://www.kulturrat.de/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Frauen-in-Kultur-und-Medien.pdf

- Both quotations from the author’s memory of conversations with the respective individuals ca. 2014.