Zerrüttete Leben, ungehörte Lieder

Am 8. September 2020 brach im größten europäischen Lager für Geflüchtete auf der griechischen Insel Lesbos, auch bekannt als die Hölle von Moria ein verheerender Brand aus. Die Flammen wüteten drei Tage lang und als das Feuer gelöscht war, war vom Lager nichts mehr übrig und 13.000 Bewohner_innen blieben völlig mittellos zurück. Der Brand war wenige Tage, nachdem die griechische Regierung angekündigt hatte, das Lager von Moria wegen Covid-19 unter Quarantäne stellen zu wollen, und nachdem auch schon die Absicht erklärt worden war, alle Lager in geschlossene Anhaltezentren umzuwandeln, gelegt worden. Moria wurde 2015 als Erstaufnahmelager für Geflüchtete, die Lesbos auf Booten erreichten, errichtet. Es sollte 3.000 Menschen aufnehmen können. Mit dem EU-Türkei-Abkommen im Jahr 2016 (auch bekannt als „Flüchtlingsdeal“), wurden geflüchtete Menschen fortan dazu gezwungen, auf den griechischen Inseln so lange zu verweilen, bis ihr Asylantrag bearbeitet worden war. Das führte dazu, dass das Lager rasant wuchs und schlussendlich um die 13.000 Menschen unter miserablen Bedingungen darin lebten. Sie mussten dort unter schlechten hygienischen Bedingungen hausen, hatten keinen Zugang zu Trinkwasser und besonders gefährdete Personen waren dort nicht sicher. Im Laufe der letzten fünf Jahre starben in Moria viele Menschen aufgrund von Kälte, Unfällen, mangelnder medizinischer Versorgung und gewalttätigen Auseinandersetzungen zwischen Banden.

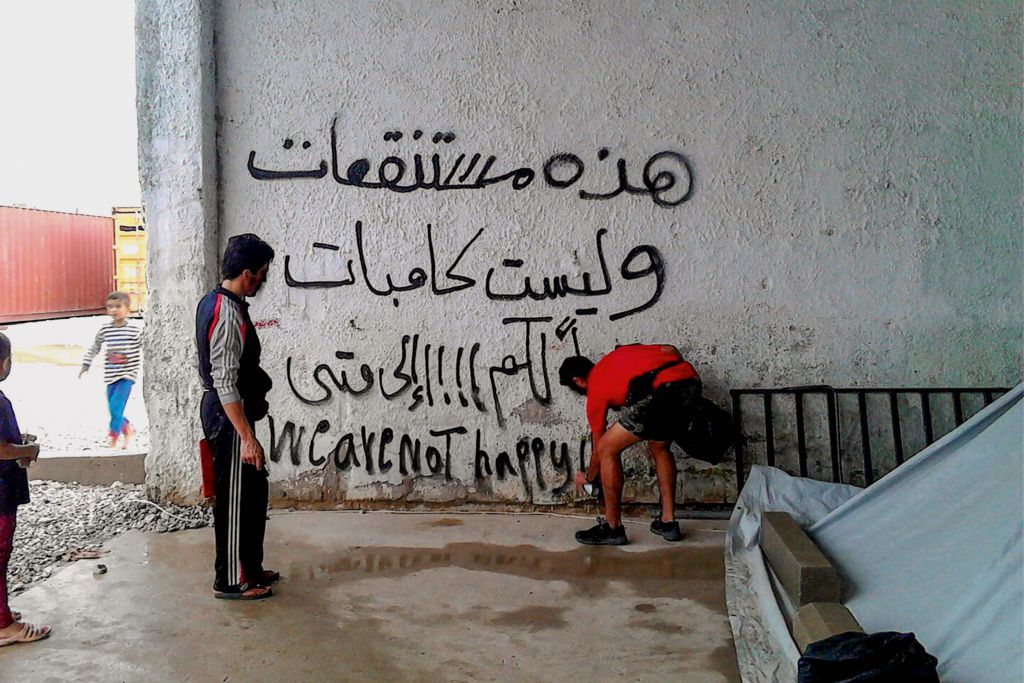

Während die Flammen wüteten, streamten viele Geflüchtete den Brand mithilfe ihrer Handys live mit. In einem dieser Videos hört man, wie eine Person fröhlich singend skandiert: „Bye-bye Moria!“ Das nahmen viele griechische Fernsehmoderator_innen zum Anlass, Geflüchtete erneut anzugreifen: „Wie können sie es wagen! Nicht nur haben sie den Zufluchtsort abgebrannt, den wir für sie gebaut hatten, sondern sie singen auch noch darüber!“ Obwohl nach wie vor ungeklärt ist, wer das Feuer im Lager von Moria gelegt hat, wurde das Singen als Beweis für die Schuld der Geflüchteten instrumentalisiert. Denn es war für all jene, die die sozio-politische Ausgrenzung und Entmenschlichung von Geflüchteten vorangetrieben hatten, und das dabei aber als „Willkommenskultur“ und Schutz angepriesen hatten, ein Schlag ins Gesicht. Angesichts des asymmetrischen Machtverhältnisses, das das internationale Recht mit sich bringt – geflüchteten Menschen wird das Recht abgesprochen, ihr Leben selbstbestimmt zu gestalten, sie sind von humanitärer Hilfe abhängig und werden in Lagern zunehmend vom Rest der Gesellschaft abgeschnitten – kann im Lager gegen diese Missstände heiter Anzusingen als Akt des Widerstandes angesehen werden. Als eine Zurückgewinnung des eigenen Rechts, politisch agieren zu dürfen, des Rechts, gehört zu werden. Musik wird so zu einem unmittelbaren Medium, um Freiheit und Menschenwürde zu leben und zu feiern, wenn alle anderen Möglichkeiten politischen Ausdrucks verunmöglicht sind.

Dies ist eine zentrale Hypothese meines PhD-Forschungsprojekts im Fach Ethnomusikologie am Music and Minorities Research Center, das den Titel Hurriya, Azadi, Freedom Now! Music in the experience of forced migration from Syria to European borderlands trägt, und die changierenden Funktionen, Bedeutungen und soziopolitischen Implikationen musikalischer Darbietungen syrischer Geflüchteter und Vertriebener im Zuge ihrer Flucht und Umsiedlung in Europa untersucht. Ausgehend von meiner Dokumentation musikalischer Performances im Sommer 2016 (in der nordgriechischen Stadt Thessaloniki, vor einem ähnlichen Hintergrund von Protesten Geflüchteter gegen ihre aufgezwungene Immobilität in menschenunwürdigen Lagern) untersuche ich die unterschiedlichen musikalischen Strategien, die von syrischen Geflüchteten und Vertriebenen verwendet wurden, als sich am Ziel ihrer Flucht, in Europa, diskriminierenden Maßnahmen ausgesetzt sahen. Von der Ausrichtung der angewandten Ethnomusikologie inspiriert, möchte ich im Musikschaffen syrischer Geflüchteter die Potenziale, die ihre soziopolitische Inklusion unterstützen können, aufzeigen und stärken. Somit ist es mein Ziel, ethnomusikologisches Wissen in der Praxis umzusetzen.

„Hurriya, Azadi, Freedom now!“ war einer der Slogans, die in den Straßen Thessalonikis erklangen, als gesungen und getanzt wurde. „Hurriya“ auf Arabisch und „Azadi“ auf Persisch bedeuten Frieden. Junge Protestierende, Bewohner_innen von Lagern für Gflüchtete, hauptsächlich syrisch-arabischer Abstammung, nutzten die Lautsprecher, die von lokalen Aktivist_innen aufgebaut worden waren, und spielten damit ihre Musik ab. Ein flotter Beat begleitet von Gesang und Synthesizersounds, die den Klang der traditionellen syrische Flöte namens Midschwiz nachahmten, füllte Straßen und Plätze. Die jungen Männer versammelten sich zu einem Kreis und begannen den Dabke zu tanzen, ein im Nahen Osten beliebter Volkstanz, der in Syrien bei Festen und Feiern wie zum Beispiel Hochzeiten gängig ist, aber auch bei den Protesten der syrischen Revolution von 2011 getanzt wurde. Andere junge Männer schnappten sich ein Mikrofon und sangen für die Demonstrant_innen arabische Lieder über die Revolution, den Krieg und ihr Leben als Geflüchtete: „Wir bleiben hier, damit der Schmerz abebbt. Hier werden wir leben und die Musik wird lieblicher sein!“1

Abgesehen von den Demonstrationen, fanden diese jungen Männer, die ihre Flucht meist alleine angetreten hatten und kinderlos waren, andere Wege, um dem eintönigen Alltag im Lager zu entkommen. Sie versammelten sich in Zelten, um gemeinsam zu singen, sie organisierten Tanzveranstaltungen für Kinder oder Wettbewerbe wie „Refugees got Talent“ und nahmen an Veranstaltungen, wie bspw. Theaterproduktionen, teil, die es ihnen ermöglichten, Anschluss an das gesellschaftliche Leben in der Stadt zu finden. Zugleich konnten geflüchtete LGBTIQ-Personen mit der Hilfe von lokalen Aktivist_innengruppen aus den Lagern entkommen. Die Formen von deren musikalischem Ausdruck waren hauptsächlich Bauchtanz und Drag-Shows, diese fanden in geschützten Räumen der queeren Community Thessalonikis statt. Und für manche Geflüchtete waren auch das Internet und die sozialen Medien ein wichtiges Fenster zur Welt, wodurch sie ihre Musik und ihre aktivistischen Tätigkeiten der Außenwelt mitteilen konnten.

Syrische Geflüchtete in Thessaloniki hatten also, wie vielleicht auch jene Menschen, die zusahen, wie Moria niederbrannte, unterschiedliche Wege gefunden, um wieder selbstbestimmter zu leben. Angesicht des Schmerzes und der Erniedrigungen zu singen und zu tanzen war eine dieser Strategien. Entgegen der üblichen öffentlichen Darstellungen sind Geflüchtete nicht „stumm“. Sie haben eine Stimme, aber diese wird ihnen allzu oft abgesprochen und durch rassistische Politiken und Einstellungen entwertet. Ich glaube, dass die Rolle einer sozial verantwortlich agierenden ethnomusikologischen Forschung über Musik von Geflüchteten, abgesehen von der Dokumentation, Analyse und dem Erschließen dieser musikalischen Darbietungen, jene sein muss, als „Sprachrohr“ und „Verstärker“ zu dienen und somit ein Medium zu sein, das die Stimmen und die Musik von geflüchteten Menschen mit dem Rest der Welt teilt, damit wir eines Tages gemeinsam gegen alle Höllen ansingen können: „Bye-bye Moria! Bye-bye Refugee camps!“

Mehr Informationen zum Forschungsprojekt finden Sie unter: musicandminorities.org/research/projects/music-in-the-experience-of-forced-migration

Übersetzung ins Deutsche: Stefania Schenk Vitale