It was ten years ago that exil.arte – then a private association – began documenting and studying the estates of emigrated Jewish musicians. And now, it is has been integrated into the mdw as a research centre with the mission of ensuring that future generations are keenly aware of the greatness and importance of this heritage.

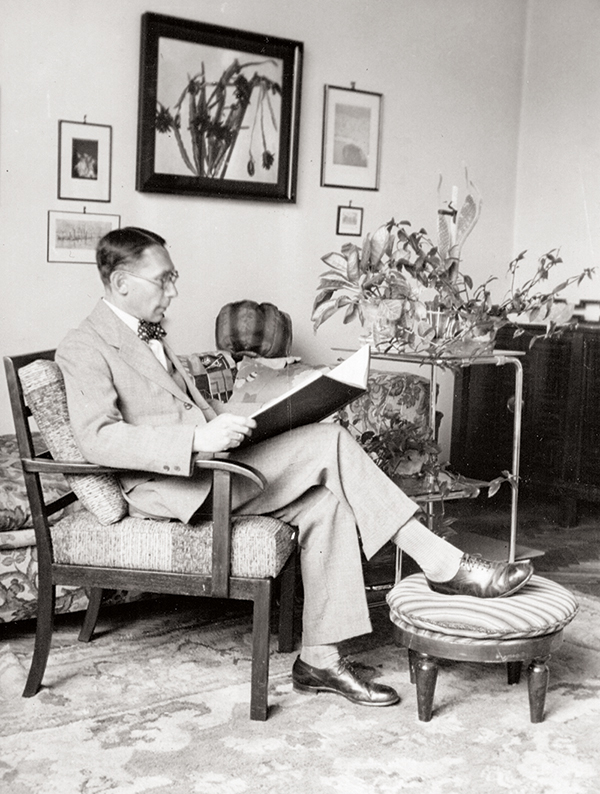

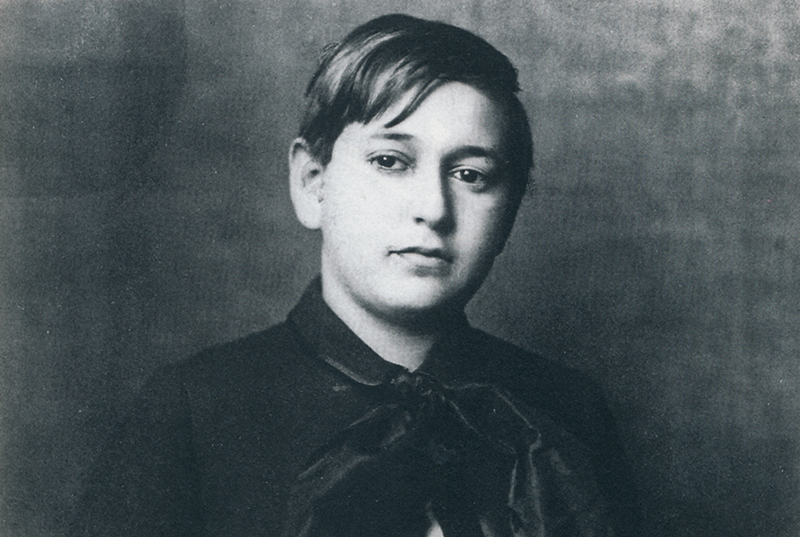

1930 ©Archiv, Eva Fox-Gál

In addition to its millions of victims in the Holocaust, National Socialism was also responsible for an unprecedented intellectual bloodletting that one can only hope will remain a unique historical occurrence. Nazi rule saw an entire generation of cultural professionals proscribed, driven into exile, or even murdered due to their religious heritage or nonconforming political stances. Those who did succeed in emigrating could count themselves lucky to have not paid for this regime and the Second World War with their lives. But even their fates had substantial individual prices.

In addition to family members, these people also lost their artistic homes. And this had grave effects, regardless of the fact that many were to continue practicing their professions – albeit under different circumstances – in exile. For as the post-war era was to prove, this was more than a break in once-promising careers. And in the case of musicians and composers, it sealed the finality of their exodus in an exemplary fashion.

Following the war, their works simply were not reinstated in programming back home, being at turns deemed either too conventional or too insignificant. The fact that this meant the forfeiture of an important piece of cultural heritage esteemed far beyond Austria’s and Europe’s borders was of little or no concern to the post-war Austrian cultural world. The fact that the cultural break of the National Socialist era was thus not overcome, but rather reinforced, thereby furthering the destruction of cultural identity, may not have been apparent to those responsible – but that changed nothing about the result.

In Austria, studying and coming to terms with this chapter of history began far later in music than in other artistic fields, and to this day, it is a project that remains incomplete. Gerold Gruber says that “dealing with the loss of that specifically early 20th-century polystylistic quality and – ideally – restoring it” is a young discipline. As a musicologist, Gruber himself once found himself feeling positively ashamed in this regard: through all his years of researching Arnold Schönberg, he had never really taken much note of the other composers around him. They represent a neglected area to which, alongside his mdw professorship, he has now devoted himself as head of the M.A.E.D. (Music Analysis and Exile Documentation Research Center) and as founder and chair of exil.arte.

Gruber found a profound ally (who is now an exil.arte Senior Researcher) in Michael Haas, director of the Jewish Music Institute at SAOS, University of London and an experienced record producer (PolyGram, Sony, Universal Music). It was during the late 1980s and as a producer that Haas first came into contact with representatives of this exiled generation. He had been asked by Decca to compile a list of those composers whose music had been performed most frequently in the years leading up to 1933. His list included Alban Berg, Hans Gál, Ernst Toch, and Egon Wellesz as well as Arnold Schönberg, Hanns Eisler, Ernst Krenek, Erich Korngold, and Alexander Zemlinksy. These composers had something in common: they were all either Viennese or Viennese-educated.

The record producer therefore assumed the core market for this music to be Austria. While this was theoretically true, reality looked different: the ORF refused to cooperate on the series, distributors refused to distribute the material, and concert venues and organisers insisted on riskfree advance financing. At any rate, the 1990s did see CDs of music by Krenek, Schreker, Zemlinksy, Eisler, and Korngold enter the market via PolyGram – but, as Haas points out, not in Austria. The resonance generated by these recordings turned out to be quite limited, and that was also the case when, as music curator of the Jewish Museum Vienna (2002 – 2010), he began having this music played at exhibitions.

In retrospect, 2006 was a key year for Gerold Gruber. Back then, the Orpheus Trust (which had been founded by cultural manager Primavera Driessen-Gruber) announced that it was shutting down. After ten years of devoting itself to the systematic research and documentation of exiled musical life, Orpheus was forced to close in the wake of “insufficient public sector interest” and “insufficient funding by cultural policymakers”. At that point, public support for the project totalled € 73,000 (City of Vienna) and € 20,000 (Austrian Federal Government), which combined to cover just a quarter of the required budget. Once the Orpheus Trust had closed, its archive – compiled over many years of publicly funded work – left Vienna for the Academy of Arts in Berlin.

It was in vain that Gruber fought to have the archived materials, especially important artistic estates, remain in Austria. But despite this setback, the private association he had recently formed – exil.arte – joined forces with the European Platform for Music Suppressed by National Socialism to do work on this important topic. The associated spectrum of tasks included not only documentation of the artistic estates scattered about the world’s archives, libraries, universities, and private collections, but also coordinating and organising projects and events of an artistic and scholarly character.

This is a monumental undertaking, as Gruber can state quite convincingly after ten years, especially since “we function as an interface for the reception, research, and preservation of works by Austrian composers, performers, and music researchers,” including – not exclusively, but especially – those “who were considered ‘degenerate’ by the Third Reich”. All this can only be accomplished thanks to support that extends across multiple disciplines and fields of work.

Compilation of an international database of artistic estates (which is publicly accessible via the organisation’s website) is moving forward, while at the same time, the body of material to be entered is also growing. Sometimes, this comprehensive reconstruction project also benefits from chance discoveries – be they in the form of boxes filled with music found in attics, or of musical instruments long believed destroyed. Like the Bösendorfer grand that was once owned by Egon and Emmy Wellesz: though it was to be auctioned off last year in London, it ultimately ended up finding its way to Vienna after all.

The organisation recently celebrated its first 10 years of existence not only with a concert series and other events, but also via its reestablishment as the exil.arte Centre with a new home in a building of the mdw. In the exhibition spaces there, it will be presenting an impression of its activities so far starting on 22 May 2017 – yet another next step towards getting coming generations of musicians and researchers excited about this segment of music history and convincing concert organisers and publishers of its worth.