From Wunderkind to “King of Violinists”

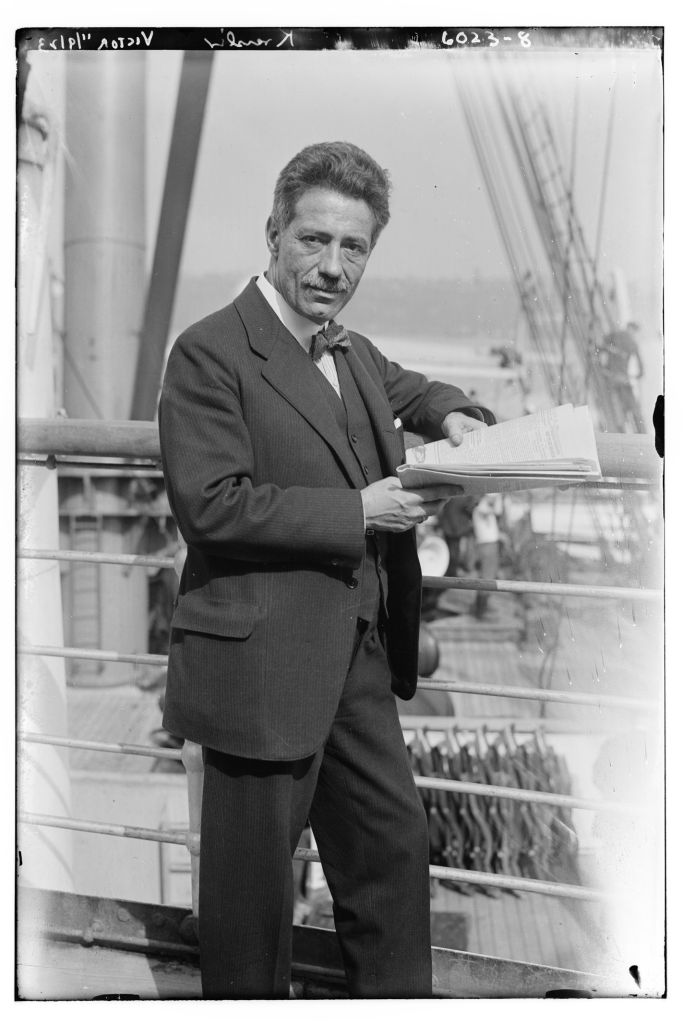

Fritz Kreisler (Vienna, 1875–1962, New York) was first taught to play the violin by his father Samuel Kreisler, a Jewish physician whose patients included Sigmund Freud. He then began studying with Joseph Hellmesberger Jr. and Anton Bruckner at the Conservatory of the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde in Wien (today’s mdw) in 1882. At age 7, he was this institution’s youngest child prodigy—and he was awarded the Conservatory’s gold medal after just three years. Following further studies at the renowned Paris Conservatory, he won that institution’s Premier Prix in 1887. There followed a successful American tour together with the pianist Moriz Rosenthal, which the two embarked upon in 1888.

After returning from the USA, Kreisler completed his general schooling with a Matura certificate, began studying medicine, and also served a short stint in the army. Though an audition to join the Vienna Philharmonic was unsuccessful, he was invited to perform together with the orchestra as a soloist. Kreisler went on to celebrate further successes with formations such as the Berlin Philharmonic under Arthur (Artúr) Nikisch. It was thus that one of the most brilliant and lucrative solo careers of that era began, with Kreisler then going on to give the world première of the violin concerto dedicated to him by Edward Elgar in 1910. His participation in the First World War as a soldier did, however, provoke a brief boycott of his appearances in the USA.

Kreisler was managed by his wife, the American Harriet Lies, who maintained quite a good relationship with National Socialist circles in Germany—and from 1924 to 1934, the two owned a house in Berlin. Her job will most certainly have been a time-consuming challenge, one that she took on with great ambition and no less success. Kreisler’s concert calendar was chock-full, and his record contract with Victor obligated him to make a great number of recordings. During this period, his so-called “Classical Manuscripts” garnered him a great deal of admiration—though the subsequent revelation that these compositions were actually from his own pen also garnered him more than a bit of criticism.

From 1933 onward, Fritz Kreisler refused to appear in the “German Reich” out of solidarity with conductors like Fritz Busch and Bruno Walter. 1935 then saw Kreisler awarded the Ring of Honour of the City of Vienna on the occasion of his 60th birthday, and radio programmes dedicated to him were broadcast worldwide. Only in Germany was he ignored. The Nazis went on in 1938 to ban all recordings and performances by him due to his Jewish origins. Kreisler received French citizenship, which was initially not recognised by Germany, but he did manage to emigrate to America together with his wife in 1939. He would become an American citizen in 1943. A 1941 car accident forced Kreisler to drastically cut back on his performing, and his final public performance took place in 1947. This magnificent soloist, whose eyesight then gradually deteriorated toward blindness, passed away in New York in 1962.

Yehudi Menuhin said of him: “The typical Kreisler sound was subtle and insistent, filled beneath its surface with emotion and impulses, with hints and allusions that the primitive recording technology of those days as well as I did our utmost to capture.” And Menuhin continued: “I yearn desperately to play ‘Schön Rosmarin’ and ‘Caprice Viennois’ with such refined elegance.” (Yehudi Menuhin, Unvollendete Reise. Lebenserinnerungen, Munich 1979, p. 68.)

An exhibition by the Exilarte Center for Banned Music at the mdw with a wide range of images, sheet music, and documents from Kreisler’s life as well as a simultaneously published catalogue will celebrate the ongoing Fritz Kreisler Memorial Year by highlighting aspects such as Kreisler’s family history, his period in Vienna, and his special knack for media relations (as exemplified by his interactions with record companies, newspapers, and broadcasters). Kreisler’s style of violin playing (in connection with the great violin concertos and Beethoven’s sonatas) will likewise be a theme, as will be his arrangements and his way of composing. Of interest are also the over one dozen violins by Stradivari, Guarneri, and other outstanding luthiers that he called his own (including mention of today’s owners). And finally, attention will be given to the historical component of Kreisler’s banishment by the National Socialist state on “racial” grounds as well as—in keeping with now-traditional practice at Exilarte exhibitions—to other exiled and proscribed violin virtuosi and string quartets of that era (Alma and Arnold Rosé, Carl Flesch, Bronislaw Hubermann, Ferdinand Adler, the Busch Quartet, the Rostal Quartet, etc.).

Fritz Kreisler – A Cosmopolitan in Exile

Opening: 16 September 2022, runs until May 2023

Exilarte Center for Banned Music

Lothringerstraße 18, 1030 Vienna

exilarte.org

Tipp:

The 10th International Fritz Kreisler Violin Competition will be held from 17 to 25 September 2022 in Vienna.

fritzkreisler.com