Of Sounds‘ Diversity: Guidance on Disturbing & Extraneous Sounds for Institutions of Healing and Learning.

2 × 7 Metaphorical Cutaway Views Concerning the Situation of (not just) Contemporary Music. A Monologic Dialogue.

° I) Insights & Outlooks:

Parents are liable for their children.

§ 1309 ABGB (General Civil Code, Austria)

Renald Deppe:

Ears are liable for their heads.

Heads are liable for their ears.

§ 1 (For self-help in the event of critical conditions, revolts, circumstances, distances, receivables, proprieties, highs, lows, emergencies, residues, and ties)

° II) Demons and Free Spirits:

“Those who cannot remember the past are doomed to repeat it.”

Ernst Bloch

Renald Deppe:

Free spirits (and we should have the good fortune to encounter not just at universities—numerous representatives of this by now rare species, at more places than just at universities!) tell us stories about our history.

About our cultural, artistic, economic, military, religious, political, and social history; about world, national, and regional history; about the history of humankind, which is always likewise part of our own personal histories. This remembering of our history requires civil courage, above all—which is not given to everybody. Which is another reason why there are so few free spirits. And so many supposedly free, servilely civil spirits.

“Civil courage begins when somebody defends a particular special situation against the overpowering tendency towards homogeneity, normalcy, linearity—or even just when one perceives said situation as ‘special’ … Civil courage is manifested as the daring feat of disrespectful thought’s hurling itself against the majority-backed pressure of normalcy, against orderliness, against the brittle smoothness of functioning… In short, that person is a dissident, and his courage is that of a solitary rhinoceros walking the earth…”

This is, at any rate, what was written by a German university professor who was suspended from his post for political reasons in 1977 (in the wake of the Buback Affair). In 1982, one year prior to his death (of heart failure), all of the disciplinary measures that had been taken against him were declared null and void. This individual was the social psychologist and psychoanalyst Peter Brückner. We should seek to encounter all those (more or less) solitarily wandering rhinoceroses with their stories about history so that (not only) all the mdw contemporaries and co-sufferers in particular and their cultural fields of reference and environments in general are spared being condemned to repeat one or the other of these joyless and dismal stories (which is to say: not solely from the history of the 20th century).

Stories of serenades and browbeatings; stories from the (nowadays) oft-so-close far-off and far-off near-by; stories about ostensible victories, inconsequent conquests and congenial consequences; tories heralding loves, shoves, and sieves (…for the holes are the most important parts of a sieve) and about the wide horizon at and the oil slicks on and the dying world under the seas; about the staying and remaining of numerous settling and uprooting, immigrating and emigrating wanderers; about the numerous disrespectful and ungodly soldiers of fortune, crusaders, and knights of the crescent moon; stories about great and small departures, also known as life…

Back when there were still princely, royal, and imperial houses and dark times, the free spirits, at least, (may have) had it a bit better as court jesters. May have. But our present-day democratically elected princes(ses) with all their publicly listed executive board emperors and –esses with their diverse houses of cards and pleasures seem not to require confirmed jesters or jesterettes. And what a fatal mistake that is!

° III) Self- & Other-Determination:

“Culture must begin with the contemporary and documentary, with the real, in order to then—where appropriate—penetrate further to the classics. The mistake of humanism: beginning with the classics. This accustoms one to the unreal, to rhetoric, and ultimately to cynical scorn for classical culture—after all, it didn’t cost us anything, and we didn’t recognise its value. (the contemporary, that they had in their time)”

Cesare Pavese (From: The Business of Living, Diaries 1935–1950)

Renald Deppe:

Study programmes (in music) should begin with the real—and should therefore effect a discursive encounter with supposed traditions as well as with the ostensibly contemporary. Anything else would be unreal. And cynical. The present-day job descriptions of all composers and musicians, with their multifarious requirements, are subject to constant change. This needs to be anticipated far in advance and accounted for in the university-level educational canon in a way that makes sense: after all, many curricula are still beholden to the museumlike, unreal cultural and intellectual life of the 19th century.

And what’s more, an (arts) university must do more than merely fulfil the (perhaps likewise often questionable) presentday demands of the cultural scene: it should also give space and attention to what lies in the future. So it should constantly, and always in a self-determined manner, be redefining and reinventing itself. Anything else would be unreal. And cynical.

Nothing destroys the gifts and talents, motivation, and wonderment of a (young) human being as comprehensively and as permanently as tenured apathy and institutional ignorance.

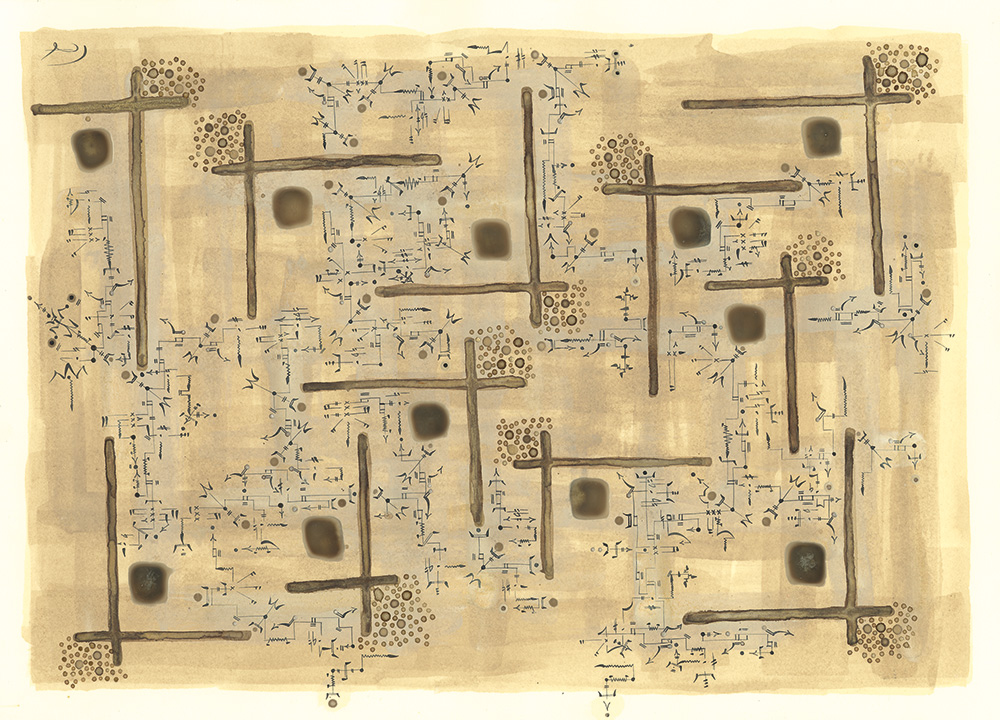

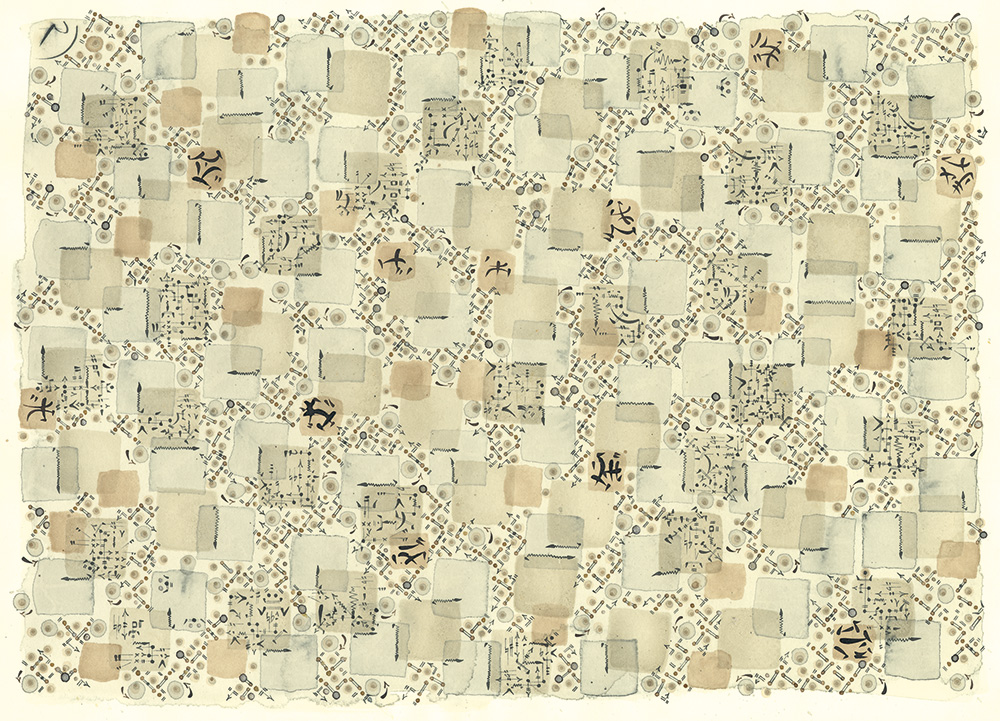

° IV) Care of Spaces & Monuments:

1. The notion of tradition is predicated on a minimum awareness of continuity in an intact society.

2. The crises associated with the development of mass industrial society during this century have destroyed said continuity.

3. Bourgeois thought is not up to handling the newly assumed tasks entailed by this reality. It shields itself with a broadly developed system of repressive mechanisms meant to cover up the isolation, alienation, fear, and speechlessness of the individual.

4. Our arts and culture are a significant part of this system of repression. In this sense, it has taken tradition captive: it preserves the illusion of a common basis of understanding that has actually long since been lost by conserving and making a fetish of historical aesthetic categories and the values associated therewith.

6. Tradition, thus taken captive by the need of a public (cultural) life lingering in anachronisms to repress precisely this fact, has thus lost its lively purpose… (To be rooted in tradition means hardly more than to be mucking about in it.)

7. Tradition, as a synonym for tabooified convention, now represents a treacherous part of our reality. It has become a latent prison.

8. But in its doings, this tradition simultaneously embodies those historical examples and artistic experiences on which attempts to break out of this prison could be based, insofar as they require any justification at all. The obligatory resistance of creativity against predetermination by the available means, along with the associated unavoidable annoyance or even shock caused by liberties taken with a thus administrated object as an unwelcome memory and warning about how freedom must be practiced, can be shown to be the actual driving force behind art throughout history to this day.

This latent tradition must be uncovered and conveyed in its contradiction of the conventional ways of upholding traditions.

Helmut Lachenmann

Renald Deppe:

As perhaps no other university (of music), the mdw is subject to and obligated to, exposed to and connected to the notions of tradition situated right here on location. Consequently, it is essential that we deal critically with the values of transformed and imagined traditional paradigms, with tradition’s joyous and frustrating legitimations, tradition’s horrific and sensible requirements, and tradition’s witty and lossy sinecures.

And it’s not just in Vienna that for the most part half-baked notions of tradition mutate into an aesthetic and artisanal norm; that they create and legitimise unspeakable banalities, resist criticism and reform, and end up being fatally reminiscent of individuals directly elected for life—be their positions political, clerical, or academic in nature. “An academically trained individual of mediocre gifts stands out for having learned things that are practical and expedient, as well as for the fact that he has lost the ability to listen to his inner sound.”

Among other things, this truly resistive and profoundly irritating sentence by Wassily Kandinsky, a freelance (Bauhaus) artist and one who taught liberating models of thought and life out of a feeling of responsibility, also helps one to arrive at a clearer view of the efforts of many composers of notes and signs to create, graphically realise, and convey acoustic events: How does one make possible the essential? The hearing of one’s inner voice?

Disregarding all normative requirements, disregarding the dominance of whatever happens to be de rigueur, disregarding the claustrophobia- and paralysis-inducing cages with all of their various heavy- and lightweight traditions. But always paying heed to the ability to criticise oneself, to the perception of collective and individual responsibility, and to one profoundly joyous fact: that education, knowledge, abilities, and skills are not and never were dependent on the attendance of university-level institutions.

In the best case, these institutions refrain from hindering, damaging, destroying, and grinding down precisely these things, proving to be helpful and instructional … but that’s almost utopian. Or at least a constant professional and human challenge for all teachers. Who are also always learners. I am. We are. That is (can be) enough.

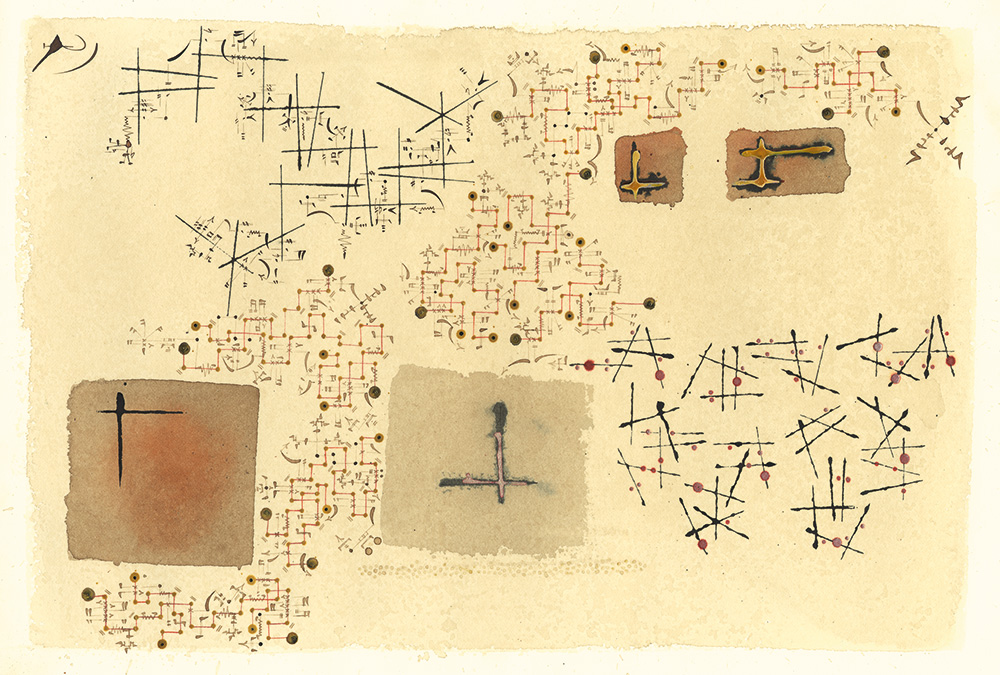

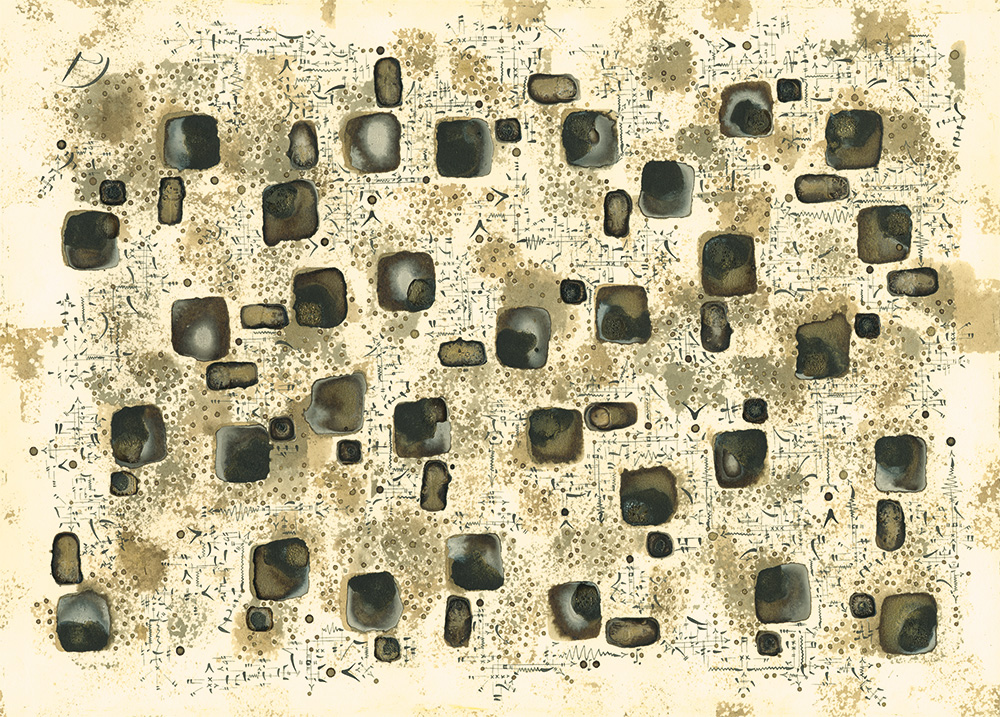

° V) A Day’s Work and Handiwork:

“The fate awaiting the work of art is the air-conditioned eternity of the museum; the one awaiting the industrial object is the garbage dump. Craftwork escapes the museum, and when it does end up in its showcases, it acquits itself with honour: rather than a unique object, it is merely a sample. It is a captive example, not an idol. Craftsmanship does not go hand in hand with time, nor does it seek to conquer it. The indecency of waste is no less pathetic than the indecency of the false eternity of the museum. Craftsmanship does not aspire to last for millennia, but at the same time it seeks no early death. It follows the course of time from day to day, flowing along with us, gradually wearing out, neither pursuing death nor denying it, but rather, accepting it. In between the museum’s time out of time and the accelerated time of technology, the work of craftsmanship is the pulse of human time.”

Octavio Paz

Renald Deppe:

It is not the supposed eternity of the museum, not the millennia-weathering genuine inspirations of a chosen few protagonists for elitist, cult-musical places of ordination and production: it is rather the (perhaps) ephemeral truth of the moment that is at the centre of the pulse of human time.

It is not the intellectual and material garbage dumps of diverse consumer, evaluatory, and devaluatory societies that should determine the action for which responsibility is taken or correct the relevant needs of (culture) creators, but the possibilities of human existence, to wit: the qualities of failure.

In order to be able to recognise, experience, and process those precious qualities of imperfection, of the damaged and defective, of the blemish and the debacle in a positive and liberating way, craftsmanship is necessary.

And it is necessary to respect and value craftsmanship in the broadest sense: as a counterpoint to the artistic dislocations of an experience of time that is moving faster and faster, as a calming island of orientation within zeitgeisty art temples’ relentlessly swelling flood of information, publication, interpretation, speculation, and conception complete with all the endlessly self-referential factories of the cultural scene and cultural education.

(And here, we should not forget that, after all, Joseph Haydn was privileged to, compelled to, able to, and did succeed in composing—among other things—107 symphonies, 68 string quartets, 24 operas, 14 masses, 46 piano trios, 126 barytontrios, and 52 piano sonatas. With his output growing more and more consummate as he went.)

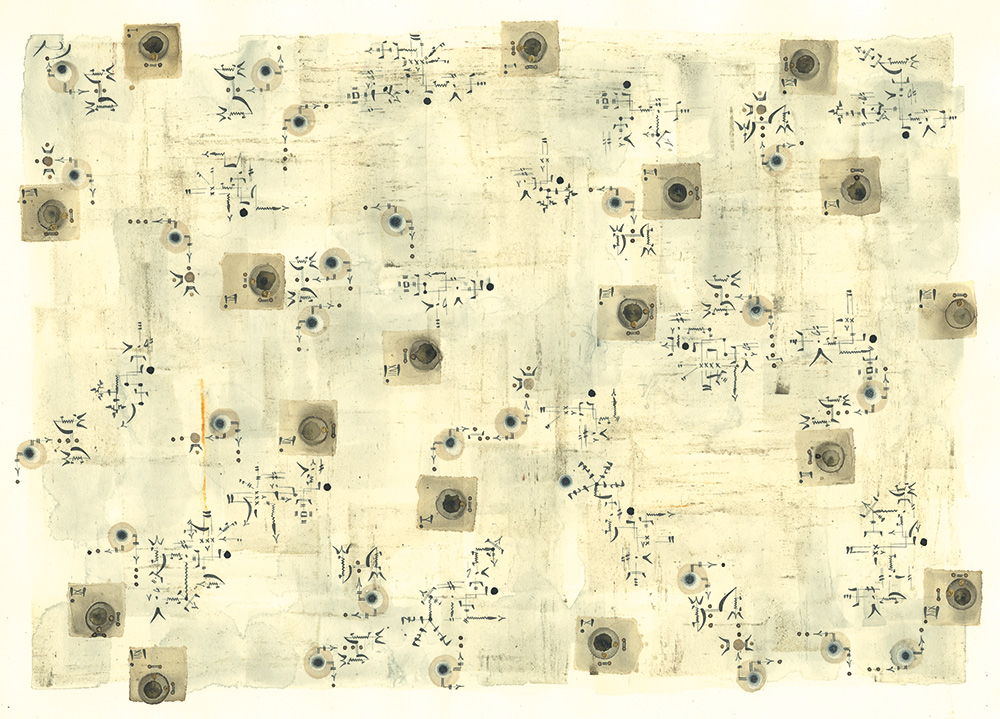

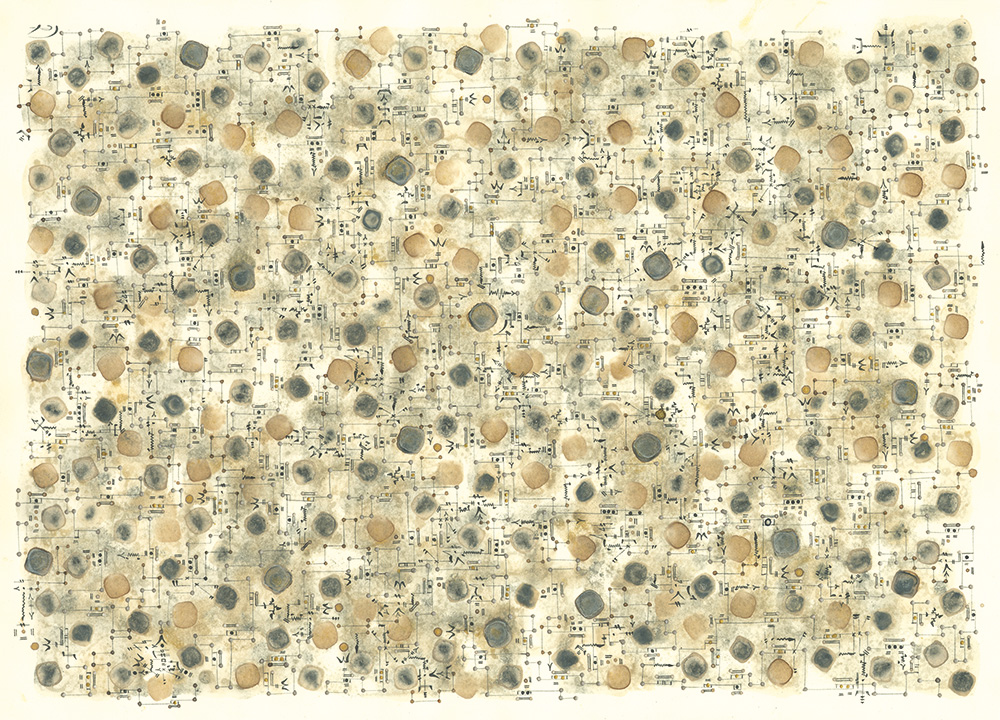

° VI) Signs & Astrological Signs:

„I speak with my hand, you listen with your eyes.“

Shitao

Renald Deppe:

I speak with my hand, you listen with your eyes.

You act with your language, I see with my ears.

I speak with my ears, you see with your hand.

You see with your language, I act with my ears.

I speak with my ears, you hear with your hand.

You see with your language, I act with my ears.

I act with my language, you see with your ears.

You speak with your hand, I listen with my eyes.

I act with my eyes, you listen with your language.

You hear with your hand, I speak with my eyes.

I act with my eyes, you see with your ears.

You see with your hand, I hear with my language.

I hear with my eyes, you act with your language.

You see with your ears, I speak with my hand.

I hear with my hand, you speak with your eyes.

You speak with your ears, I see with my hand.

I hear with my hand, you act with your eyes.

You act with your ears, I see with my language.

I see with my ears, you speak with your hand.

You hear with your eyes, I act with my language.

I see with my language, you act with your ears.

You act with your eyes, I hear with my language.

I see with my language, you speak with your ears.

You speak with my eyes, I hear with my hand.

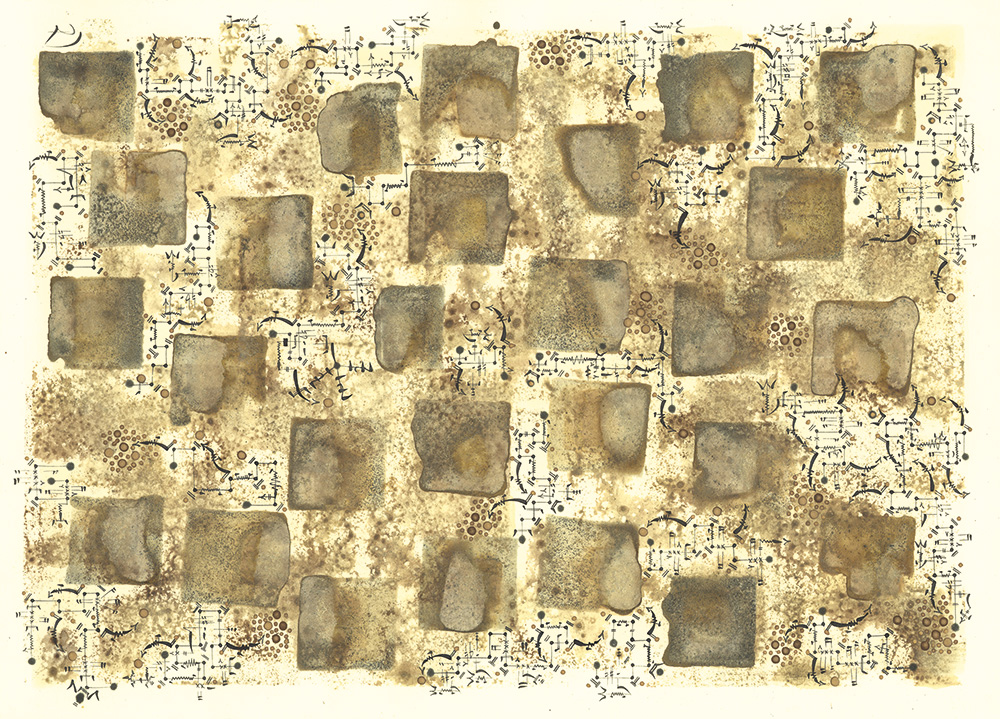

° VII) Absence & Presence:

„Good travellers leave behind no trace nor track.“

Laozi

Renald Deppe:

Good tracks leave behind no travellers.

All graphic notations are by the author Renald Deppe.

Translator’s note: in several passages of this text, its author makes use of the flexibility and ambiguity of the German language—often in the form of plays on words and prefix substitutions—as inspiration for the actual content of his reactions to the quotations he presents. While the closeness of English and German vocabulary means that some of these translate quite well into English, others do not. The normal approach to translating “untranslatable” plays on words, puns, and the like would be to find English-language substitutes that have similar effects, but the fact that such substitutes often entail different content makes this approach unsuitable, here. Therefore, in the interest of coherency, some passages of this text have been translated strictly in terms of content, which unfortunately fails to do justice to the verbal virtuosity of the original.