Ulrike Demal is a clinical psychologist, a psychotherapist (specialised in behavioural therapy), a therapist trainer (for ÖGVT, the Austrian Association for Behavioural Therapy), a supervisor, and a teacher (Medical University of Vienna), and she also works in the Clinical Psychology Department of Vienna General Hospital’s Medical Directorate—Medical University Campus, University Clinic for Psychiatry and Psychotherapy. In the following, she provides mdw Magazine with a basic overview of anxiety and fear—of what they are and how they arise.

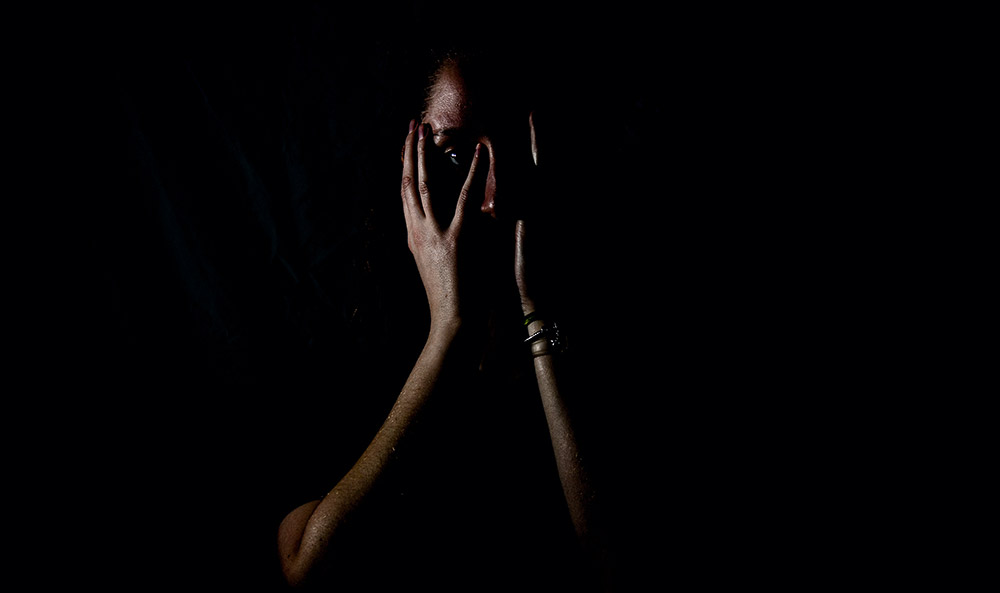

Fundamentally, one can distinguish between anxiety as an unpleasant, diffuse feeling not directed towards a specific trigger and fear as a reaction to a certain object, stimulus, or concrete situation (e.g. a wild animal, a thunderstorm, a fast-approaching car, etc.). Both are acute emotional states—and distinct from anxiousness as a personality trait.

The basic response in play here is a natural instinct and of the greatest evolutionary relevance. Over the course of evolution, the only creatures that survived were those equipped with a perfect hyperarousal system capable of triggering an unconditional fight-or-flight response to any dangers that arose. Anxiety and fear therefore make sense and are necessary as an alert (warning the organism of dangers and directing attention to the dangerous situation at hand), as preparation of the body for fast action (mobilising strength and activating the musculature to either stand and fight or run away), and as an automatic alarm response (since dangerous situations require fast action).

A certain measure of anxiety and fear is absolutely normal. Though both are experienced as something unpleasant, they’re usually not dangerous but rather just indicative of a natural response that’s biologically hard-wired in our bodies.

Anxiety and fear express themselves physically (in forms such as an accelerated pulse and elevated blood pressure, sweating, trembling, and dryness of the mouth), cognitively (evaluations, interpretations, expectations, self-dialogue, etc.), emotionally (helplessness, being overwhelmed, shame, etc.), and behaviourally (avoidance, flight, help-seeking, freezing in place, etc.).

Many aspects of such responses manifest themselves as what we call stress in our everyday lives. Every day, every human being experiences a multitude of weaker and stronger stressors that evoke stress responses of varying intensity. The nature of a stress response is influenced by the strength of the stressor, one’s general level of agitation or degree of adaptation, and one’s subjective evaluation of how threatening the situation is. A person’s general level of agitation and/or degree of adaptation can be positively influenced by getting sufficient sleep, engaging in regular physical activity or sport, relaxation exercises, healthy and balanced nutrition, refraining from the excessive consumption of alcohol, cigarettes, and coffee, stress-reducing leisure activities, pleasurable social contacts, resolution of chronic interpersonal conflicts, and reduction of overwhelming situations’ frequency of occurrence.

But this mechanism can also turn pathological—in the form of an anxiety disorder—if it’s inordinately intense, recurs too often, or coincides with a loss of control, as well as when clear avoidance behaviour develops and/or anxieties give rise to real-life limitations and/or psychological strain.

One can distinguish between the following anxiety disorders:

A panic disorder is characterised by sudden and unexpected attacks of anxiety without a definite trigger that come with various physical symptoms (e.g. a pounding heart, chest pains, a choking sensation, dizziness, etc.) and associated concrete fears (like of suffering a heart attack).

In a generalised anxiety disorder, exaggerated worries and apprehensions about diverse aspects of life, combined with nervousness, insomnia, tension, etc., are most prominent.

Agoraphobia consists in strong but unfounded anxiety with regard to being in crowds, on mass transit, etc. Affected individuals fear that help will be unavailable and that escape will be impossible when physical symptoms arise.

Social anxiety disorder has to do with the expectation that one might be negatively judged or evaluated by others in social situations, not least due to this disorder’s physical symptoms—which can include sweating, blushing, and trembling.

There are also specific phobias that relate to specific objects and/or situations: animals, natural forces, blood, syringes, injuries, heights, flying, etc.

Possible Causes

Theories of cognition assume that people suffering from anxiety perceive and assess situations and physical symptoms as being more dangerous than they really are and adapt their behaviour accordingly.

Biological theories describe an elevated degree of vulnerability: the autonomic nervous system, which regulates internal organ functions such as the heartbeat, digestion, and breathing, is particularly prone to agitation by various stimuli. These can cause physical symptoms to be more strongly perceived, increasing the probability of anxiety or fear as a reaction. In the brain, the amygdala is directly involved in the production of fear, while the hippocampus has to do with processes of learning and memory. The prefrontal cortex (frontal lobe), on the other hand, is responsible for assessing fear-stimuli and planning reactions to them. And neurotransmitters such as serotonin and noradrenaline, as well as GABA (gamma aminobutyric acid), also have a role to play.

According to the assumptions of learning theory, intense anxieties and fears arise via classical and operant conditioning. While classical conditioning is assumed to be involved in their creation, operant conditioning plays a significant role in their maintenance: triggering situations are avoided, and the absence or elimination of anxiety or fear is experienced as a relief. Avoidance therefore upholds anxieties and fears by preventing corrective learning experiences and corresponding re-assessments from taking place. Furthermore, learning via the observation of models can also have an influence.

Therapy

Anxiety disorders respond well to treatment, with both psychotherapy (above all behavioural therapy) and medical therapies now well-established.