What is togetherness and how do we achieve it when performing music as a group?

Why togetherness?

The FWF-funded research project “Achieving Togetherness in Music Ensemble Performance”, based at the Department of Music Acoustics – Wiener Klangstil, aims to shed light on the experiences of togetherness that arise during music performance. Little is known about how togetherness, the experience of sharing a cognitive-emotional state with co-performers, contributes to creating a successful performance, or how audiences perceive togetherness that emerges between performing musicians.

What is togetherness?

Togetherness is an experience that reflects the quality of interaction between people who are working on a shared task such as music-making. This feeling can change from moment to moment as the quality of interaction changes. In periods of high togetherness, collaboration between group members seems effortless. There’s no need to negotiate with each other or actively predict each other’s plans, because everyone already knows what the other(s) will do. Some musicians speak of sharing a “hive mind” with other ensemble members. Periods of high togetherness are intrinsically rewarding. In periods of very low togetherness, in contrast, collaboration requires more effort. Achieving shared goals is difficult, and the group’s individual members have to work to figure out what the others are doing. This experience can lead to fatigue and frustration.

How do audible and visible cues shape audience perceptions of togetherness?

One of the questions that our project addresses is how readily audiences perceive togetherness between performing musicians. A recent experiment investigated the cues that audiences use to judge togetherness in music that they hear and see.

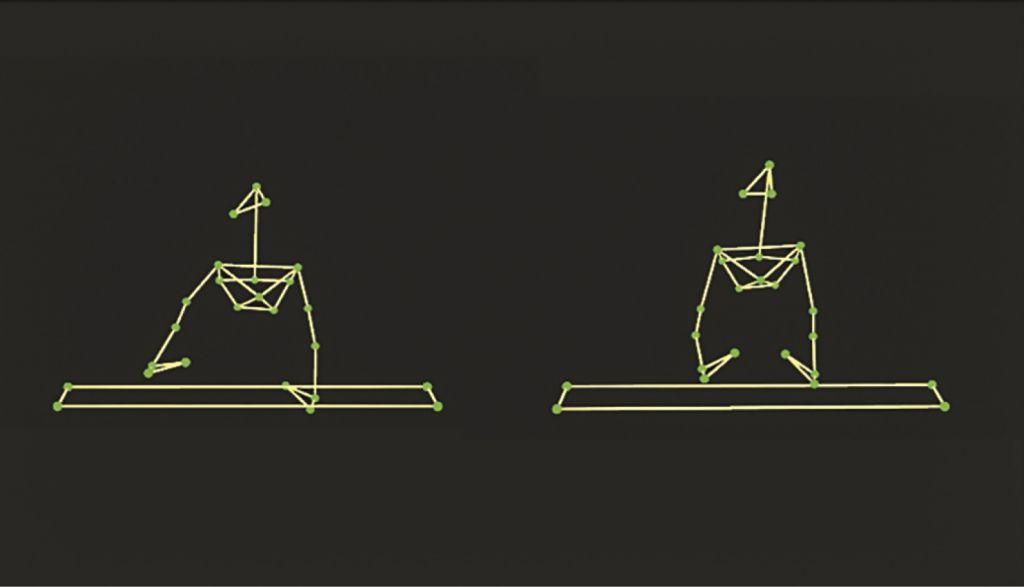

We invited musical novices and semi-professional musicians to come to the lab and watch recorded performances of a short piece of music, played either by two pianists or by two clarinettists. These recordings were made with an infrared motion capture system that tracked the spatial trajectories of markers placed on different parts of the musicians’ bodies. In the experimental stimuli, the performers were shown as moving “point light” displays (see illustration 1). Participants could either see and hear, only see, or only hear the performers. During the experiment, participants wore eye-tracking glasses that recorded precisely where in the video display they looked from moment to moment. While watching and/or listening to the recordings, participants rated the strength of togetherness that they perceived.

Novices’ ratings of perceived togetherness were higher overall than those of semi-professionals, perhaps because the semi-professionals have more strict criteria for judgements of quality in others’ performances. Novices also rated stimuli with greater sound intensity as being more together than did semi-professional musicians, suggesting that semi-professionals may distinguish more between togetherness and expressive intensity than novices.

How do empathy and expressive body-based interaction between performers support their experiences of togetherness?

We also recently carried out a large-scale performance study with piano-and-singer (Lied) duos. This study sought to create a collection of multi-modal data that could be used to show how experiences of togetherness relate to specific behaviours and physiological states. One of our aims was to show how behavioural interactions between performers are affected by their capacities for empathic perspective-taking—a cognitive ability that affects how readily people relate to each other. People with high empathic perspective-taking abilities are able to predict others’ behaviour more easily than people with low empathic perspective-taking abilities. We hypothesised that the strength of bodily interactions between performers as well as the strength of togetherness-experiences would relate to performers’ empathic profiles.

We measured participants’ body motion using motion capture technology and recorded the gaze direction of the musicians with eye-tracking glasses. We also recorded audio, video and MIDI from the piano. Participants wore ECG sensors to track heart activity and belts around their chests and abdomens to capture respiratory movements. Each duo recorded a few performances together and then watched recordings of their performances while rating the togetherness that they remembered experiencing during the performance.

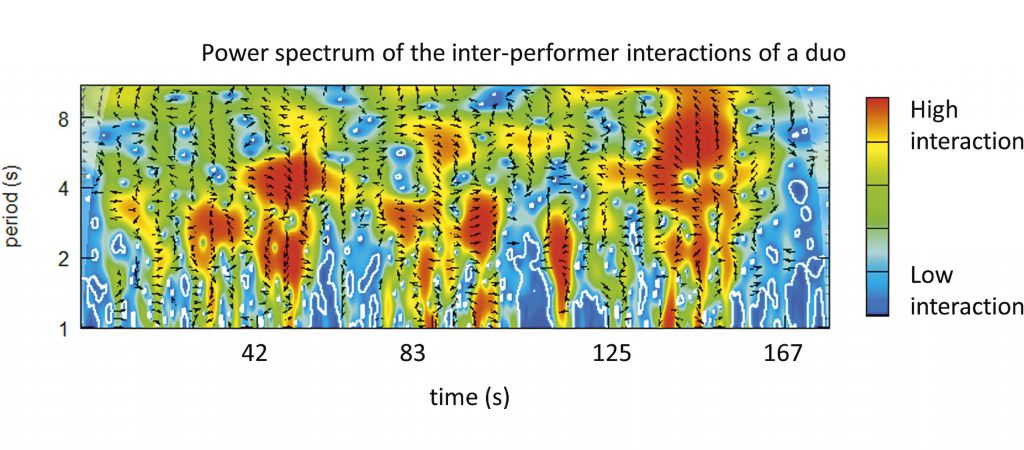

Some of our analyses looked at how similarly the singer and pianist moved and how strongly they influenced each other through their bodily motions (see illustration 2). We were especially interested in the musicians’ expressive head motions. Our preliminary findings show that when a musician who is high in empathy is paired with a co-performer who is low in empathy, the high-empathy performer tends to lead the low-empathy performer through their head motion. So, if a high-empathy singer plays with a low-empathy pianist, the singer leads; if a high-empathy pianist plays with a low-empathy singer, the pianist leads. This is an interesting result that contradicts the idea that stronger empathy enables better following. Our results instead suggest that stronger empathy can enable better leading.

Complex interpersonal interactions like those that support successful ensemble playing are difficult to measure. Musicians’ cognitive-emotional states and experiences are especially hard to access and relate to quantifiable measures like sound synchronisation or quantity of body motion. With a novel mixed-methods approach to studying performance, our research should lead to an improved understanding of how strong relationships between performers enable high performance quality.

As a final note, we wish to thank all of the wonderful musicians who have been participating in our research! It is a pleasure working with them and hearing the inspired, high-level performances and interpretations that they create together.

Further information at mdw.ac.at/togetherness

Authors: Anna Niemand, Sara D’Amario, Werner Goebl, Laura Bishop