Markus Grassl in Conversation with Pier Damiano Peretti

Markus Grassl (MG): The reason for our conversation is your new critical edition of Arnold Schönberg’s sole completed work for organ, Variations on a Recitative op. 40, for Universal Edition. Perhaps we should begin by touching on the salient features of the work itself.

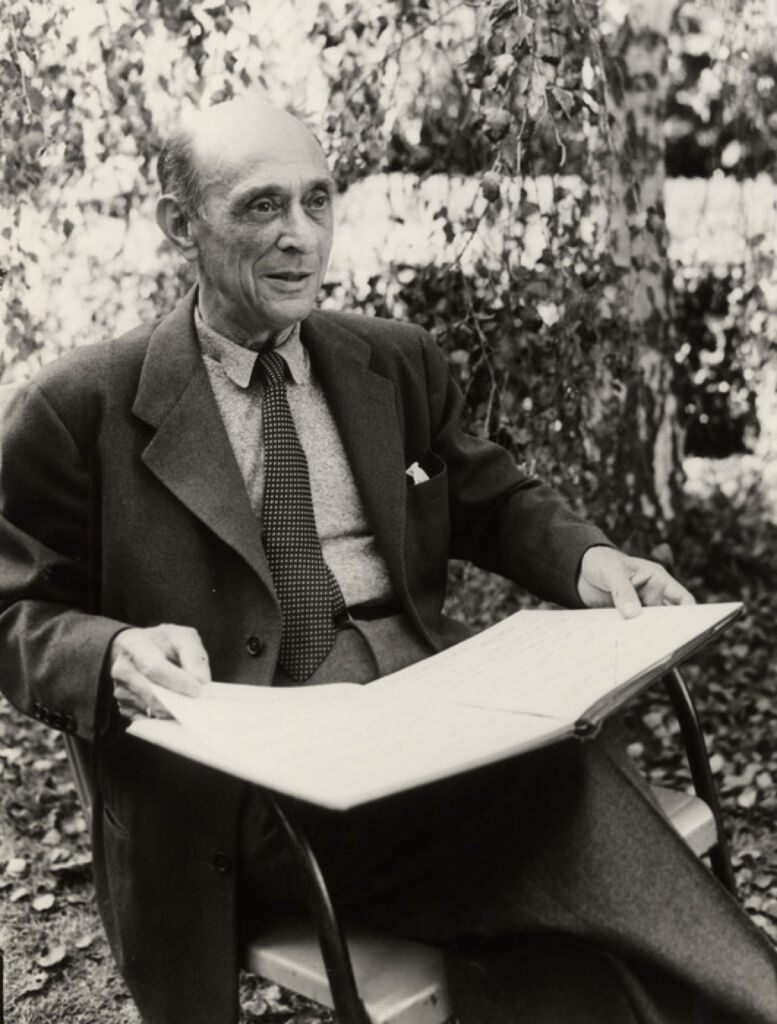

Pier Damiano Peretti (PDP): It was composed in 1941 in response to a commission by Gray Publishers in New York for a series initiated and edited by William Strickland, a well-regarded American organist and conductor, that was devoted to the publication of works for organ by composers living in the US. Carl Weinrich, director of music at Princeton University, premièred the piece three years later in New York. And a further significant figure here was Eduard Steuermann, who was involved organisationally and in preparing the performance—as one can read in the correspondence between him and Schönberg held at the Schönberg Center.

MG: Schönberg, in a letter to René Leibowitz, described his op. 40 as “my ‘pieces in the old style’”. And the composition—which consists of 10 variations on a theme initially presented without accompaniment, a transitional “cadenza”, and a fugue—does in fact exhibit a number of features reminiscent of earlier music.

PDP: Yes, running all the way from Bach—especially his Passacaglia for Organ—to Reger. The widespread general association of the organ with counterpoint was probably also a factor. But by the same token, features typical of Schönberg’s composing are also present in the form of extremely dense motivic and thematic work as well as borrowings from processes that we know from twelve-tone music.

MG: The same also goes for the work’s particular harmonic tendencies. Op. 40 belongs to this small group of later tonal works—so it rests clearly upon a central note. But it also refrains quite decidedly from making use of traditional functional harmony based on fifth relationships.

PDP: Yes, it’s much rather based on a system—worked out by Schönberg in extensive sketches—that approaches the chromatic space in its very own way, such as in progressing by semitones between chords comprised of layered thirds and of layered fourths.

MG: Let’s turn to the edition itself. At first glance, one might be surprised that a work by Schönberg would need a new critical edition. However, op. 40 does represent an especially complex case from a philological and editorial standpoint.

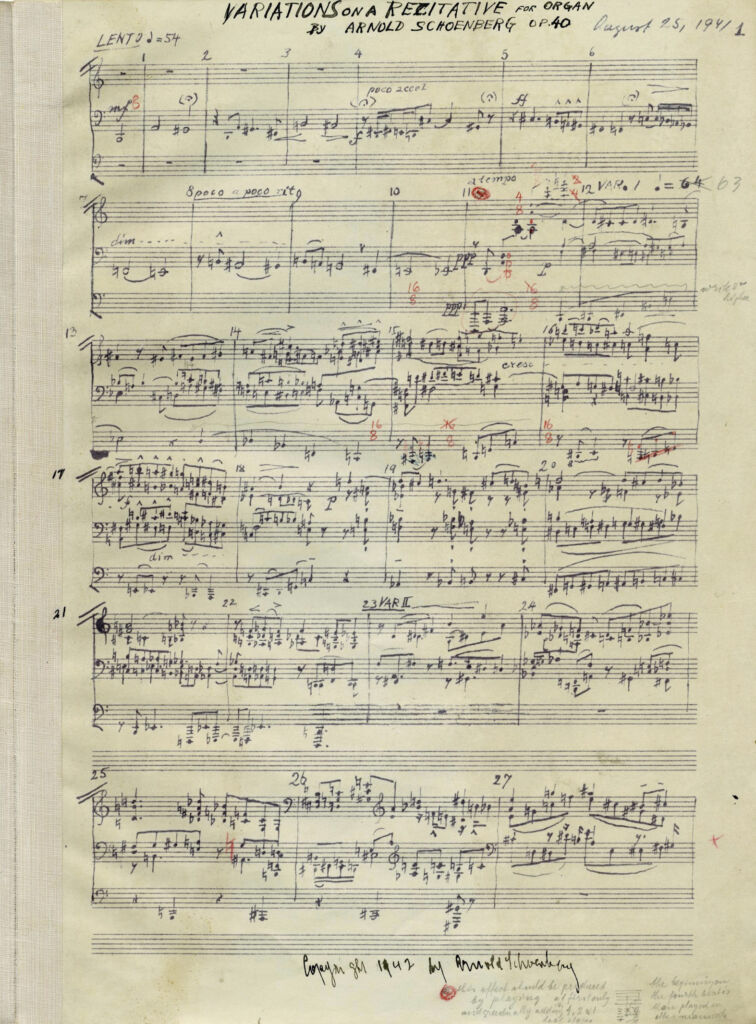

PDP: That’s owed to its similarly idiosyncratic autograph notation. As had been his practice since 1917, Schönberg made use here of “result notation”—in other words, he wrote the pitches that were to be heard by listeners. In the pedal part, this entails the notation of pitches not present among the pedals themselves that are only heard in the requisite registration. Moreover, Schönberg forgoes the usual foot-indications in favour of his own labels (like “col 8 basso” instead of “with 16-foot”) for registration-dependent octave doubling. The consequence was that the publisher ended up releasing an adapted version prepared by Weinrich in 1947 instead of this, if you will, “un-organistic” notation. While this does serve to convert the original into user-friendlier “action notation”, Weinrich also added copious registration instructions that were geared entirely to his own organ in Princeton with its typically American combination action.

MG: …leading to difficulties realising the piece on other types of organs.

PDP: Yes, and it followed that organists from outside the US were quick to express their annoyance to Schönberg concerning that edition.

MG: One then sees how Schönberg himself gradually became dissatisfied with Weinrich’s edition to the point where he wholly rejected it, despite how the publisher and Weinrich had involved him in its preparation.

PDP: One can even demonstrate how a number of articulation instructions that weren’t yet in the autograph but appear in Weinrich’s edition can indeed be traced back to this preparatory and/or correction work and thus to Schönberg himself.

MG: The other edition that’s been available so far is the one produced in 1973 by Christian Martin Schmidt as part of the Arnold Schönberg Complete Edition. Its problem, though, is that it returns to the impractical result notation…

PDP: …and to Schönberg’s idiosyncratic ottava indications.

MG: Could you describe what your new edition aims to do? I assume it’s about making available a scholarly and philologically well-founded text that also takes practical performance considerations into account?

PDP: Right. That means using action notation and conventional foot indications for the pitches in the pedals and the octave doubling called for by Schönberg. It was also necessary to figure out variants that are more plausible from a practical perspective in a number of individual passages, since some of the solutions found in the Complete Edition are debatable. In order to do so, it was necessary to collate a number of sources: the sketches, the autograph, the revisions that Schönberg added later to a diazo print of the autograph (see illustration), the Weinrich edition, and a source that hadn’t yet been accounted for in the earlier editions—namely, an errata list that Schönberg had sent to Strickland prior to the end of 1941 that contains corrections and addenda as well as remarks concerning his intentions in terms of timbre.

MG: In connection with Schönberg’s op. 40, we definitely shouldn’t neglect to mention Michael Radulescu, the important organist, composer, and long-time mdw organ professor—who was also your teacher. Did you work on this piece with him?

PDP: Yes, and I actually ended up playing it for my diploma examination. Schönberg’s Variations were a fixture of Radulescu’s teaching. He’d himself spent quite a long time with the piece—first in his studies with Anton Heiller, who likewise dealt with it regularly in his class. Radulescu went on to perform it repeatedly in concert programmes and also subjected it to analytical and philological study, which eventually led to a 1982 essay published in the journal Musik und Kirche that also provided me with some points of reference for my own edition. I now hope that this edition will give the work a renewed “push”—because, viewed internationally, it still leads quite a marginal existence both in the organ repertoire and in Schönberg reception at large.