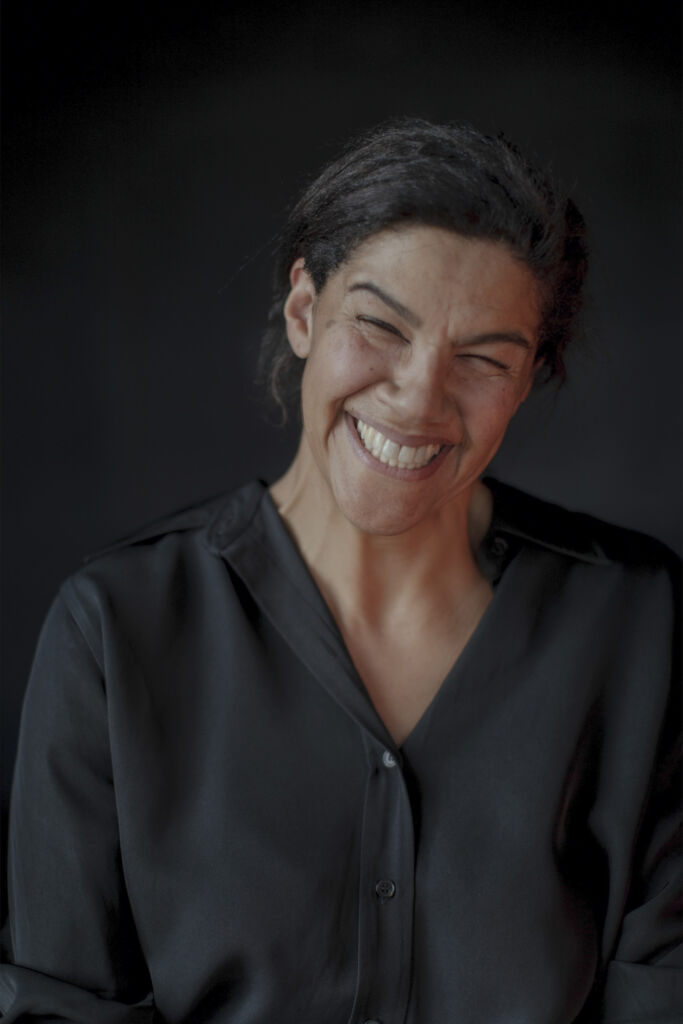

Elizabeth Blonzen has been teaching the subject of Role Development at the Max Reinhardt Seminar since October 2024. In the following, the actor and playwright tells mdw Magazine why Vienna is the ideal city for actors, how one goes about cultivating courageous acting personalities, and why people at the Max Reinhardt Seminar might allow each other a little something more.

“Hast heard no news of Barbara to-day?” “Of Barbara?” “Yes, hast heard no news of Barbara to-day?” “If I’ve heard news of Barbara?” If one hears this Faustian question thrown back and forth again and again, it can hardly be a traditional performance. It’s more likely to be an exercise based on this famous scene—as occurs frequently in Role Development class at the Max Reinhardt Seminar.

In this subject, students in all four years of the programme work together on one or several scenes from classical plays. The point is to have students try out various roles with an ability to jettison them if they don’t suit. This is important to Elizabeth Blonzen, who was appointed as a professor of role development at the Max Reinhardt Seminar this past October: “My ambition is to find roles that are well suited to the students’ respective states of training—roles that push them forward but don’t make them so insecure that they lose their enthusiasm or get discouraged,” she says in explanation of her approach. The purpose of exercises like the one described above is to find out what you “really want to know from the other person—and what the other person wants to know from you.” For this is ultimately what one wants to show society: that people should listen to and take an interest in each other.

Openness to one’s colleagues onstage, the joy of experimentation, the courage to make mistakes: in the eyes of Elizabeth Blonzen, all of these things are core elements of role development. Students “should also be able to try something out that they’re not sure will elicit any applause.” After all, it’s common to encounter a role that one can’t really get a handle on initially—but where it is indeed rewarding to keep at it. “It’s great when they learn to forgive themselves for having failed to do something well. My desire is to train actors who press on courageously even when things aren’t going so great,” Blonzen says. This is, she says, what she’s always done herself.

The actor, playwright, and acting professor, who was born in 1968 and trained at the Otto Falckenberg School of the Performing Arts in Munich, appeared in major classical roles quite early in life and went on to be engaged by various theatres including the Munich Kammerspiele, Hamburg’s Deutsches Schauspielhaus, the Bochum Schauspielhaus, and both the Schaubühne and the Maxim Gorki Theater in Berlin. She has also been seen in numerous television and cinematic productions. At present, Blonzen is concentrating mainly on her work at the Max Reinhardt Seminar—a job in which she’s found quite some fulfilment: “I’m totally blown away by my students. Teaching them is a true joy. An honour. We’re currently working on a comedy, Oscar Wilde’s Bunbury, and I think they’re so funny and enchanting in everything they wrestle with, everything they come up with, and everything they sometimes come up with in order to avoid having to come up with anything.” On weekends, she catches herself already looking forward to her favourites among the passages she’ll be working on in upcoming lessons—and to pass the time until then, Blonzen will sometimes even construct Advent calendars for her charges. “Just like my students, I, too, still have to figure out my role here at the Max Reinhardt Seminar; we’re all starting and supporting each other together.

Just like many of her students who only moved to Vienna just recently, Elizabeth Blonzen is a new arrival. “Vienna’s a city where actors are still valued, loved, and respected,” says Blonzen, laughing, of her new hometown—where, contrary to the usual (and rarely disproven) cliché, she’s received a consistently friendly welcome so far. It’s something she’s also experienced at the mdw’s acting school. “The Max Reinhardt Seminar trains ensemble-oriented actors,” says Elizabeth Blonzen of her observations here. The students “are capable of playing as partners, they do it truly with each other; there’s no elbow-mentality. They devote themselves to the play, to the character, to the situation that they’re supposed to act out.” And while post-dramatic theatre à la Elfriede Jelinek and “frontal monologues” are indeed a thing at the Reinhardt Seminar, people here are also fond of performing together. “They do so like at no other acting school. Which, I think, is partly because of Vienna,” says Blonzen.

A strong group identity also includes the encouragement of diversity, which is becoming more and more of a factor at the Max Reinhardt Seminar. “One needs to ensure in a structural sense that one’s not just superficially admitting a few diverse students but also hiring people at the leadership level or for things like technical positions who can enrich the team with different perspectives.” This, says Elizabeth Blonzen, needs to take place at a central decision-making level. “It’s also one reason why I’m here, since I hope that something will change structurally with this new leading team.” One example of the steps taken by the Max Reinhardt Seminar so far has been a workshop on gender diversity, a topic quite close to students’ hearts. And as far as Blonzen is concerned, it should also be obligatory for teaching faculty to attend a workshop on anti-racism or to have engaged with the topic artistically. That, she says, would engender respectful interaction at the Max Reinhardt Seminar as well as an atmosphere of “allowing each other to be great.” But there’s also something else, says Blonzen, that underlies this: “Trust is the basis. And the basis of this basis is self-confidence.” This is one of many things that need to be conveyed in Role Development class, she says. Independent development of roles and co-determination of how they’re filled out along with playful, experimental interaction in a safe environment need to be cultivated. This also includes the ability to make decisions: “Do we want to leave a work in the era in which it was written, or should we play it in the present day? What costumes should we choose? How are the characters dressed? A corset? Or something comfortable? What aesthetic do we want? How should we approach it? Do we want to declaim everything as a choir? How would that be different? How does our idea of female and male look? Do we want to leave things in the originally intended genders? Or should a woman play Hamlet? What’s our stance on that?”

In the Oscar Wilde play currently being rehearsed, for example, they’re discussing how one should deal with a character’s description as a “young, pretty girl.” “Does it hurt the character if she’s spoken about in such a way? How do we deal with the fact that existence in relation to a man is the most important thing, here? Do we want to reproduce that, or do we want to oppose it with something?” These are important questions that need to be asked and worked through in Role Development. Making all of these (in part artistic) decisions should enable students to self-confidently take creative action and attain independence from the directorial level. It’s partly for this precise reason that acting and directing students at the Max Reinhardt Seminar are taught together during their first year. “We want to train actors who can proceed independently. Who don’t wait to see what the director suggests. Who offer directors something, and who view themselves not just as accessories but as artistic partners.” Acting students also learn how they should engage with directors’ demands—including aspects like standing up for their rights and establishing boundaries. “If you’re not having that great a rehearsal, you might lack the confidence to say, for instance, that the agreed-upon rehearsal period is already over. You’ll think: ‘I was so bad just now that I can’t also go and make demands’.” It’s precisely this phenomenon that Elizabeth Blonzen seeks to counter most decidedly in her teaching: “To my mind, the main goal isn’t for her to be a fantastic Gretchen. While that would be nice, my primary concern is to enable her to discover her own artistic personality and employ it in a self-confident manner—and to go forth from her work with me with more self-assurance than before.”

Whether the students have actually heard any news of Barbara remains secondary.