Cellist Anmari van der Westhuizen gave a presentation entitled Cross-Cultural Sounds: South African Contemporary Solo Cello Works on 15 November 2024 at the invitation of the Alma Rosé Department. Van der Westhuizen earned her cello diploma in Stellenbosch, South Africa and then continued her training with Heidi Litschauer at Mozarteum University Salzburg and with Maria Kliegel at the Cologne University of Music. Alongside her activities as a soloist, Van der Westhuizen is employed as a cello professor at the Odeion School of Music of the University of the Free State in Bloemfontein, South Africa and also serves as artistic director and conductor of that institution’s Camerata. Moreover, she is the lead member of the Odeion String Quartet—which is the only resident string quartet at a South African university.

Ms. Van der Westhuizen, your musical focus as a soloist is on the contemporary cello repertoire. What was it that sparked this enthusiasm?

AvdW: Alongside my studies in Austria I played in a large number of contemporary music ensembles including Ensemble On Line and the Koehne Quartet, as part of which I came to know and love a great many contemporary works. That enthusiasm has remained to this day: I continue to engage with this repertoire and also commission new works for solo cello, and such compositions are always an important part of my concert programmes.

Your website contains a catalogue with solo repertoire for cello. When did that come into being?

AvdW: I started it as part of my dissertation on contemporary cello works, and it’s updated on a continual basis. A new entry in 2024 was Murmurs of Hope, which I commissioned from the South African composer Andile Khumalo.

You recently gave that work its Austrian première. What makes it special?

AvdW: To answer this question, I’ll first say a bit about South Africa. The country is widely known as a rainbow nation, and it has no fewer than eleven official languages. Each of these languages is associated with an independent cultural group. My country’s political situation is characterised by its complex history of colonisation, apartheid, and subsequent transformation into a democracy. Since the collapse of the apartheid regime during the 1990s, the country has been undergoing significant changes. Unfortunately, these changes include inequality, corruption, and a high rate of unemployment. But even so, South Africa is the African continent’s most politically and economically influential country. The country’s rich cultural mosaic is reflected by its unbelievably diverse musical heritage. This is comprised of the various African ethnic groups’ indigenous musics, the influence of Western classical music during the colonial era, and the birth of new popular forms from the marriage of African rhythms with jazz, gospel, and dance music. The atmospheric piece Murmurs of Hope is inspired by the old African tradition of observing the Pleiades, a constellation collectively viewed as heralding the coming of spring—a season of renewal and of growth—as well as the promise of a new beginning and hope for a better future.

What other African influences and/or stylistic devices can be found in works by South African composers?

AvdW: South African music developed in a context where various African, European, and Asian cultures came together, often under difficult social and political conditions. This melding gave rise to a unique musical landscape and what would become an extremely diverse music scene. Following apartheid, South Africa ushered in a new era where freedom of opinion was concerned. And its classical music, though historically tied to the European tradition, also started to reflect the nation’s various voices and different histories. Through the melding of African folk elements with European classical structures as well as with occasional jazz and electronic elements, there arose an unmistakable South African sound that still is, however, based on Western classical music tradition. The way I see it, there are two main approaches that South African composers take in lending expression to their music’s interculturality: the one is the fusion of traditional African melodies, rhythms, and instruments with modern musical styles, while the other—seen, for instance, in the work by Andile Khumalo—arises against the backdrop of Africa’s mythology and natural environment.

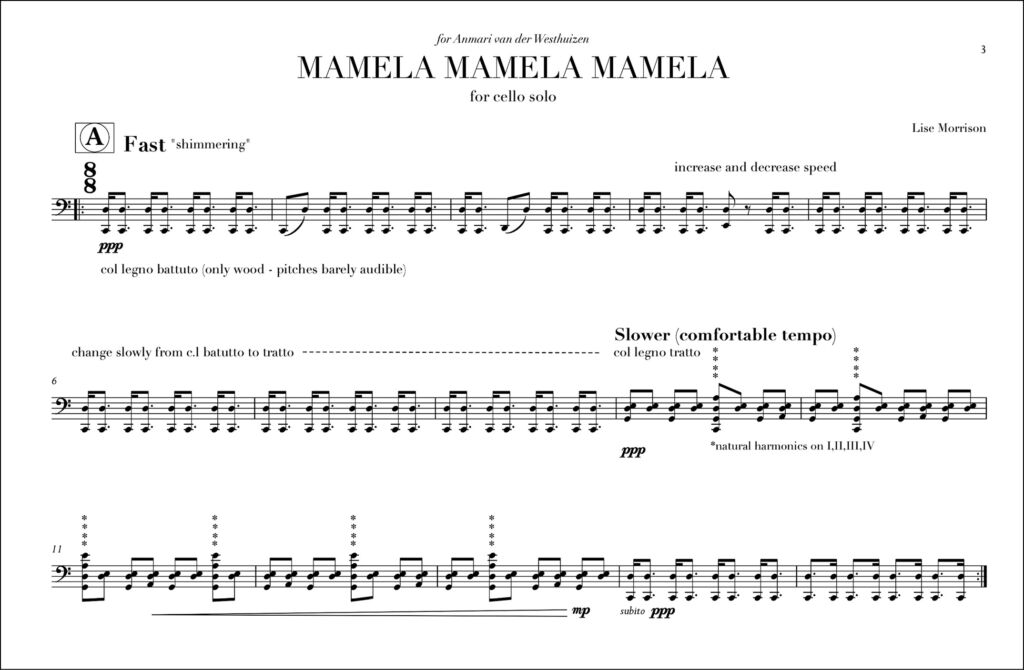

In your repertoire, one also finds the compositions Mamela Mamela Mamela by the Den Haag-based South African composer Lise Morrison and Ugubhu by Hans Huysson. What are the stories behind these titles?

AvdW: The piece Mamela Mamela Mamela was originally composed for violin in 2017, and this cello version was arranged specifically for me by the composer. Lise Morrison is known for her minimalist approach that combines African rhythmic patterns with sparse, meditative textures. Mamela means “to listen” in isiXhosa, which is one of South Africa’s official languages. The piece begins in the rhythm of this word as spoken. The word ugubhu, on the other hand, denotes a single-stringed, bow-shaped instrument used in isiZulu music. It can produce up to three notes plus three overtones, and these are used to realise both melodies and accompaniments. Hans Huysson, in his work Ugubhu for solo cello, attempts to transcend the cultural boundaries between Africa and Europe by setting a modern cello in relation to the ugubhu, the traditional African bow.

What place, in your view, does the cello occupy in South Africa’s musical landscape?

AvdW: The cello, traditionally associated with Western musical repertoire, has found a unique and still-developing voice of its own within the South African musical landscape. The cello’s special ability to produce a broad palette of textures makes it possible to explore entirely new worlds of sound. And since the pentatonic scales and melodic repetitions that are common in indigenous African music can be expressed quite effectively thanks to the cello’s tonal breadth, composers have been using this instrument to bridge cultural boundaries.

You’ve just presented two concerts and a lecture in Austria, bringing us your country’s music as an ambassador.

AvdW: When musicians and composers exchange works that draw upon their cultural backgrounds, they open up a dialogue that extends beyond the realm of words and unlocks new perspectives for listeners from different parts of the globe. Such exchange strengthens not only the classical genre but also worldwide connections between artists and audiences. And in this way, the South African solo cello repertoire can serve as a bridge that encourages cultural understanding and deeper esteem for my country’s musical contributions on the world stage.